Index

Purple In Excelsis: It's Good to Be King

Between the last time I saw Deep Purple in 2014 and this show at FivePoint, Deep Purple's long and sometimes stormy career had a change in fortune: In 2016, this veteran band, one of the Big Three of pioneering Britmetal along with Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, was elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, with hordes of fans, colleagues, and adherents cheering, then sneering, "It's about fucking time!"

"Mea Culpa"? Not Really. Mea Thinking Differently Now, Is All

Certainly the guy I saw at the Pacific Amphitheater in 2014, the one in the purple T-shirt with the declaration "Fuck the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame" emblazoned on it, will have to dye that shirt another color. (Perhaps blue, for Blue Öyster Cult?)

And I freely admit that I have in the past consistently argued against Deep Purple's inclusion in the Rock Hall, adding that I was doing so even as a teenage Purple fanatic who snapped up every Deep Purple album I could find (and afford). I did so in 2013, in 2014, and again in 2016, the year in which the band was elected, repeating the argument that with such a short glory period (the first half of the 1970s) and with just two albums, Machine Head (Warner Bros., 1972) and Made in Japan (Warner Bros., 1973), that hit on all cylinders all the time, Purple did not have a legacy as strong as its contemporaries Sabbath or Zeppelin.

Eligible since 1993, Britmetal pioneers Deep Purple finally earned its induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2016.

I still feel that way although now I don't have a problem with the band being in the Rock Hall. That's not because I'm now on the bandwagon, or I've stopped trying to swim against the tide. It's because of two realizations, one internal and one external, both related to each other.

Internally, I had, for years, been trying to evaluate legacy for the Rock Hall in terms of the "small Hall," or a Hall of Fame with a high bar of admittance, such as in the series of "audits" of artists already inducted that I had written for this site. (This audit for Part 6 contains links to the previous audits.) Yet at the same time, I willingly accepted—and still do—a broad scope of musical styles that could fit under the umbrella of "rock and roll" and thus the Rock Hall.

Externally, I watched the Rock Hall fumble and flail to put out a ballot every year that had no ongoing logic and consistency to it but rather seemed to be an arbitrary sampling of various genres across different eligible eras, and then I watched the results that the voters returned. At the same time, I watched fans' reactions to the results until the cries of "travesty!," "Hall of Lame!," "ridiculous!," "Hall of Shame!," and similar indignant condemnations eventually settled into an inchoate, angry, ever-present buzz.

But by now, I've concluded that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is fundamentally flawed, if not outright broken, and it will take fundamental changes to fix it. I've detailed the problems and have offered possible solutions—not just Band Aid fixes—last year in an article titled "What's Wrong with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?" so I won't rehash it all here except to summarize. The three fundamental issues are that there is no standard definition of "rock and roll," there are no objective evaluation criteria that can be universally applied to candidates, and because the music continually evolves, expands, and diversifies, the Rock Hall cannot help but be inclusive and expansive in response.

However, the Rock Hall uses a Hall of Fame selection and voting model similar to that of the Halls of Fame for the "Big Four" North American team sports—baseball, basketball, football, and hockey—that is a recipe for failure. Why? Because those Halls service competitive team sports that are clearly defined, that do have objective, universal evaluation criteria, and because those sports have stopped evolving fundamentally, they expand in relatively tiny increments and do not diversify fundamentally; thus, their respective Halls of Fame are restrictive and exclusive.

By contrast, we can't define what "rock and roll" is. Even if we could, we have no way of objectively evaluating who is "better" than who, or even what a minimum threshold of "good" or "worthy" would be. And even if we managed to control those variables for selected subsets of "rock and roll," the music keeps changing and growing. As a dearly missed old boss of mine liked to put it, we're just shoveling shit against the tide. Hint: the tide's going to win.

So, let 'em in. Why not? The problem now is throughput—how do we get 'em in fast enough? The current method is not only grossly inefficient, it is also more like having only a couple of clerks at a crowded Department of Motor Vehicles who are picking the numbers not in a random manner (random means with an equal probability of selection), but in an arbitrary manner—picked at best by individual discretion or preference but more likely in a capricious or unreasonable manner. Yes, sir or madame, you'll get your license renewed. It's just a matter of when I say when.

Deep Purple wasn't snubbed for the Hall. It just had to wait in a long line and at the whim of the clerks running the counter. Join the club, buddy. Most everybody else has the same problem.

So what if Deep Purple is the kid brother to Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin who doesn't quite measure up to either one? It took me a long while to realize that that small-Hall thinking simply doesn't work when pop music has been continually growing and changing since the mid-1950s. The number of acts that could be considered for the Rock Hall keeps growing, and trying to limit that number is pointless because as the music expands, of course the number of candidates is going to grow correspondingly. And at the end of the day, how many fans are going to really care as long as their favorites get in?

So, in seeing Deep Purple again, I wanted to see how the band performed knowing that it had finally earned what could be considered the ultimate accolade: induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

"The Time Has Come to Say Sayonara"

Deep Purple started The Long Goodbye tour in Eastern Europe in May 2017 amidst hints that this could be the band's last big tour. To bowdlerize a Mark Twain quote, reports of rock bands announcing retirements are often proved premature, especially as Purple has been one of the hardest-gigging bands in rock: It has participated in a concert tour in every year since 1993, with the Rapture of the Deep world tour stretching from 2005 to 2011.

But drummer Ian Paice suffered a minor stroke in 2016, and he turned 70 this year, which also marks the 50th anniversary of Deep Purple's formation. And with keyboardist Jon Lord's retirement from the band in 2002 (he died in 2012, age 71), Paice is the last original member of a group that has undergone a number of musical and personnel changes since its inception in 1968.

Although Deep Purple released its 20th studio album, Infinite (earMUSIC), last year, it did not play any cuts from it at FivePoint, but the band did roll out one track from Now What?! (Eagle, 2013), which Purple had been promoting during the 2013-to-2015 tour that I had caught last time. During the band's one hour and twenty-minute set, it touched on high points that encompassed the breadth of its half-century-long career, leaning heavily on the band's marquee studio gem, Machine Head, while sampling its earliest songs to almost its most recent ones, a retrospective that had the air of a lingering fond farewell.

Deep Background on Deep Purple

Way back in 1968, just north of London, Lord, Paice, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, bassist Nick Simper, and singer Rod Evans founded Deep Purple, taking the band's name from the title of Blackmore's grandmother's favorite song, a 1930s big-band standard.

Signed to the American Tetragrammaton recording label (Parlophone in the UK), Deep Purple cranked out a pair of albums in 1968, Shades of Deep Purple and The Book of Taliesyn, that exhibited as much pop and progressive-rock influences as hard-rock ones. In fact, the band was tagged as the poor man's Vanilla Fudge—and given the bombast associated with that organ-heavy American act (just check out its overbearing take on the Supremes' "You Keep Me Hangin' On"), it was hardly a compliment.

Shades of Deep Purple yielded a cover of American songwriter Joe South's "Hush," which was a big hit single in the US, reaching Number Four on Billboard's Hot 100 Singles chart, but it failed to generate much interest in the UK. Similarly, a cover of Neil Diamond's "Kentucky Woman" (from The Book of Taliesyn) broached the American Top 40 but sank in the UK—moreover, it underscored the band's continuing lack of songwriting prowess although the sharp instrumental "(Hard Road) Wring That Neck" hinted at the future.

Deep Purple (Tetragrammaton, 1969) did feature material composed almost entirely by the band, with Jon Lord having a hand in each of the album's six original tracks. (The seventh track was a cover of Donovan's "Lalena.") Listeners familiar primarily with the band's trademark hard rock will still be surprised by the progressive-rock and even classical motifs that swirl through the tracks "Chasing Shadows" and the closing opus "April," although the conventional rocker "Why Didn't Rosemary?" is a wry, veiled paternity lament ("why didn't Rosemary ever take the pill?") and the non-album single "Emmaretta," highlighted by Blackmore's wah-wah guitar, recounts Evans's epistolary attempt to seduce a cast member of the musical Hair. Both provided additional clues as to the band's eventual direction.

Lord's compositional ambitions spurred him to compose a Concerto for Group and Orchestra (Tetragrammaton, 1969), recorded live with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Malcolm Arnold, which would make even the Moody Blues blush with embarrassment although it did provide the band with its first commercial success in the UK. Nevertheless, band members were not enthusiastic over this direction. It was time for a change.

Deep Purple's Smoking High-Water Mark

By 1970, Deep Purple shelved the musical pretense and, like Jack Palance's Curly Washburn in City Slickers, concentrated on its one thing: hard rock. Two key personnel changes helped the band accomplish that. With Rod Evans already sounding overmatched on Purple's heavier material, he was shown the door along with Nick Simper. Replacing them were singer Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover; Gillan had been approached to join Purple previously (ironically by Simper) although he had declined, but when asked this time, he accepted, with Glover, who had tagged along, added after being vetted by Paice. Thus was born Deep Purple Mark II.

Both Gillan and Glover had already appeared on Concerto for Group and Orchestra, but they and the three originals all made their presences felt on Deep Purple In Rock (Harvest/Warner Bros., 1970), the first of the band's milestone albums, which from the opening rocker "Speed King" streamlined the quintet's firepower with the forceful Roger Glover-Ian Paice rhythm team driving the front-line attack balanced between Ritchie Blackmore's quicksilver guitar and Jon Lord's equally fleet keyboards.

However, the biggest improvement came courtesy of Gillan, a powerful, melodic singer who had performed as the title character on the original recording of the Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar (which also featured future disco diva Yvonne Elliman as Mary Magdalene); reputedly, Rice had offered Gillan the role based on Gillan's vocal performance on In Rock's centerpiece "Child in Time," on which Gillan's operatic shrieks provided inspiration for heavy metal singers to follow—not the least being Judas Priest's Rob Halford.

Purple's next album, Fireball (Harvest/Warner Bros., 1971), continued in the same vein as the title track, "Demon's Eye," and especially "Strange Kind of Woman," which became a concert staple—including at the FivePoint show—remain fan favorites. (The UK release of Fireball contains "Demon's Eye" as "Strange Kind of Woman" was released as a single, while the US release reverses that configuration.)

But with the release the following year of Machine Head (Purple/Warner Bros.), Deep Purple entered the big leagues with a signature album that spawned a number of definitive tracks: "Highway Star," "Never Before," "Lazy," "Space Truckin'," and especially "Smoke on the Water," whose guitar riff became to rock what the first four notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony are to classical.

Even better was Made in Japan (Purple/Warner Bros., 1973), originally a two-LP live set from the Japanese leg of the Machine Head world tour that Purple's Japanese label insisted on releasing. The band was unenthusiastic about the project—but Made in Japan became another seminal album, arguably Deep Purple's finest as the seven tracks on the original release surpass the studio originals. Certainly the four Machine Head songs—"Highway Star," "Smoke on the Water," "Lazy," and "Space Truckin'"—brandish superior energy and execution, and it's no spoiler to note that each factored prominently into the band's thirteen-song set at FivePoint.

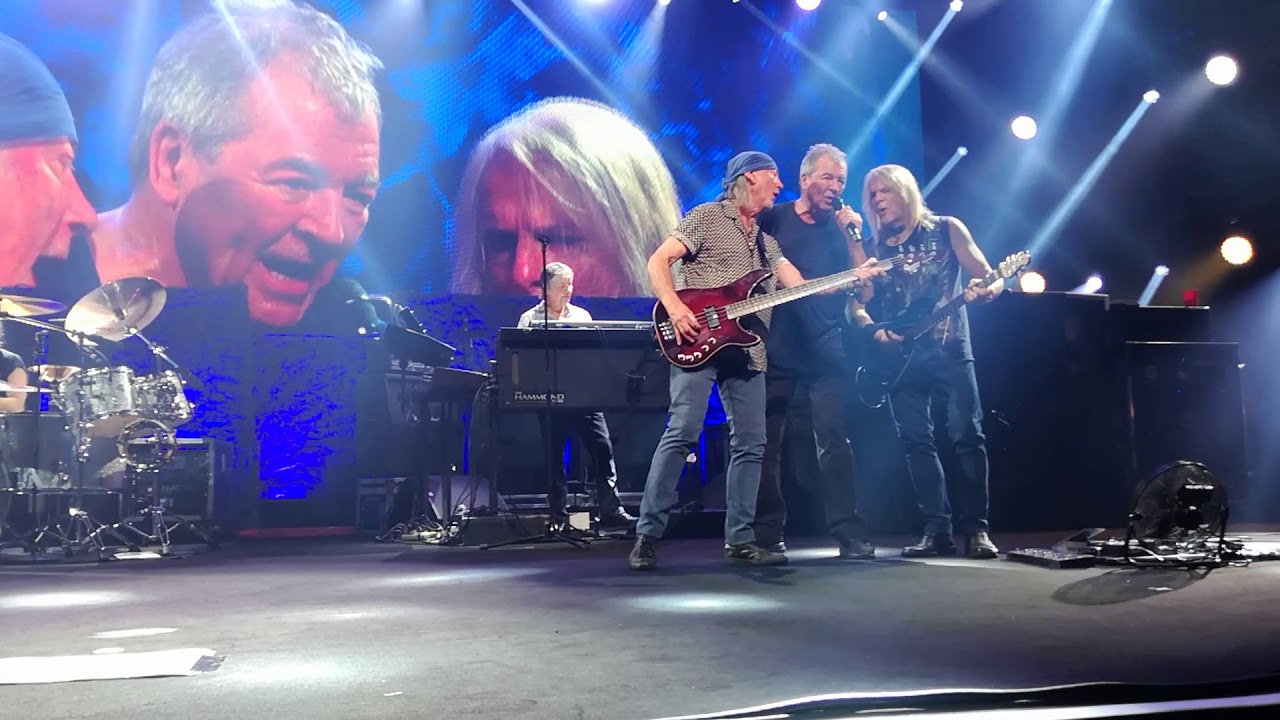

Celebrating its 50th year as hard-rock mainstays, Deep Purple drew heavily from its early-1970s glory period at FivePoint Amphitheater.

However, internal dissention and a grueling work schedule began to take its toll. Apart from the strong opening rocker "Woman from Tokyo," Who Do We Think We Are (Purple/Warner Bros., 1973) quickly faded to ordinary save for the riffy "Rat Bat Blue," although "Mary Long" took an uncharacteristic stab at social comment. Then tensions among the band members, particularly with the mercurial Blackmore, came to a head when Ian Gillan and Roger Glover walked out in 1973.

Singer David Coverdale and bassist-vocalist Glenn Hughes were recruited as replacements for a pair of studio albums, Burn and Stormbringer (both Purple/Warner, 1974), before Ritchie Blackmore quit the band in 1975. The axe-slinger, on the short list of top-flight rock guitarists of the 1970s, proved a tough one to replace although the band regrouped with young American guitarist Tommy Bolin for one album, Come Taste the Band (Purple/Warner Bros., 1975), before excessive drug usage by both Bolin and Hughes proved too much and Deep Purple broke up in 1976. (Bolin died of a drug overdose, aged 25, later that year.) Although Burn and especially the fiery title track showed promise, it seemed that the flame had died out, as evinced by the lackluster live set Made in Europe (EMI/Purple, 1976), hardly a patch on Made in Japan.

At this point, Deep Purple, which for a moment in the early 1970s had challenged even the mighty Led Zeppelin as hard-rock titans, seemed destined for nostalgia-mongering not long after that. Prospects of a reunion seemed dim: Blackmore struck first, forming Rainbow with singer Ronnie James Dio in 1975. Coverdale formed Whitesnake in 1978, with Jon Lord and later Ian Paice joining him, while Gillan formed an eponymous hard-rock outfit that same year. Meanwhile, the band sued original vocalist Rod Evans for fronting a bogus version of Deep Purple.

Then, in 1984, the Mark II lineup—Blackmore, Gillian, Glover, Lord, and Paice—not only reunited, it picked up almost where it left off with a new album, Perfect Strangers (Polydor/Mercury, 1984), and a world tour to support it and the pair of singles, the title song and "Knocking at Your Back Door," which would remain in the band's live repertoire for more than 30 years.

But it wasn't too long before tensions between Blackmore and Gillan arose once—or twice—more as Gillan was fired in 1989, with former Rainbow vocalist Joe Lynn Turner taking his place. Gillan returned in 1993, a year that marked Purple's silver anniversary, but continuing conflicts soon prompted Blackmore to quit, this time for good. American guitar whiz Joe Satriani filled in for Blackmore in order to complete concert dates, but as he was unable to join Purple permanently, the band elected former Dixie Dregs axe-slinger Steve Morse in 1994.

Except for Don Airey's taking the retiring Jon Lord's place behind the bank of keyboards in 2002, Deep Purple has remained remarkably constant for its last quarter-century. Purpendicular (RCA/BMG, 1996) was Morse's first album with Purple while Airey debuted on 2003's Bananas (EMI/Sanctuary, 2003), and although 2013's release Now What?! was a strong progressive-rock showing, Deep Purple is still largely celebrated for its 1970s glory period.

And following the band's 2016 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, that glory period remains front and center as this seminal hard-rock band celebrates its golden anniversary.

That Old Familiar Fire: Losing Some Heat?

Having begun The Long Goodbye Tour in Europe in May 2017, Deep Purple was wrapping up the North American leg of the tour that had begun in Cincinnati this August; the band is slated to play several dates in Japan in October before winding up the tour in Mexico the following month. And after that?

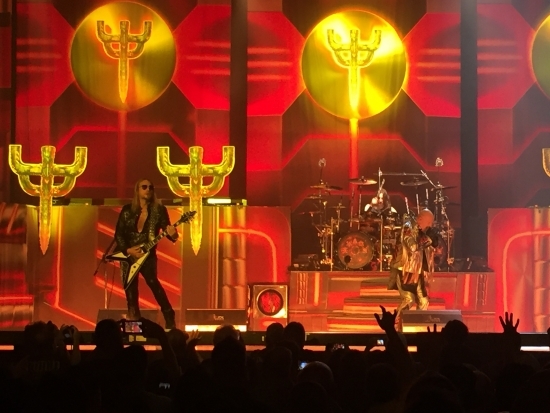

As the lights dimmed following Judas Priest's set, I was not encouraged initially—Deep Purple's walk-up music was the same as it had been when I saw the band four years ago: the "Mars" movement from Gustav Holst's The Planets orchestral suite. That sense of déjà vu carried over to Purple's opening number, the hardly-unexpected "Highway Star," and as when I'd seen the band in 2014, this prime Purple touchstone sounded as if it was being tossed off with a sense of obligation rather than with enthusiasm. Not that anyone could blame the band—how many times had Purple played it in the more than 45 years since it had been released?

But then the band dived right into a pair of rocking deep cuts—and singer Ian Gillan, who when I'd seen him previously became revitalized only when the set turned to some of the newer songs, seemed engaged immediately once he started belting out "Pictures from Home," from Machine Head, and "Bloodsucker," the sole artifact from In Rock (although Purple re-worked the track as "Bludsucker" on the 2002 album Abandon [CMC International]). Gillan remained buoyant as he and the instrumentalists tore into the concert staple "Strange Kind of Woman," the one about falling in love with the "working girl," with Gillan and Steve Morse gamely reeling off the vocals-guitar give-and-take Gillan and Ritchie Blackmore had immortalized on Made in Japan.

Deep Purple's musicianship, and that includes Gillan's forceful, assured singing that had been commanding in his prime, has never been called into question. That remained the case when Morse, then Airey, joined the fold. Morse established his axe-wielding credentials when he founded the jazz-rock fusion outfit the Dixie Dregs (later simply the Dregs) in the mid-1970s, buttressed by the accolades he has accrued throughout his career.

Similarly, Airey can boast an extensive resume supplying his classically-trained keyboards—and at age 70 he does look like a music teacher poised to chide you, albeit gently, for not practicing your scales—for a host of hard- and progressive-rock acts ranging from Black Sabbath, Ozzy Osbourne, and Judas Priest to Jethro Tull and the Electric Light Orchestra. Underpinning the pair are the sturdy rhythm team of bassist Roger Glover and drummer Ian Paice, who have been playing together for nearly a half-century.

However, Purple's songwriting has been its weak link ever since its inception, which might be why the band, unlike its contemporaries Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, had not been considered a shoo-in for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (Eligible since 1993, Deep Purple was first nominated in 2013 and again in 2014 before crossing the threshold in 2016.) So, while the band sounded sharp—and even enthusiastic—on those early songs that kicked off its set, listening to some of those lyrics now couldn't help but make me feel a bit embarrassed for the band. Which is why the relative absence of later songs—only four of the fourteen numbers were from 1984 or later, with only one that was initially released in the 21st century—gave Purple's set the air of nostalgia-mongering.

Not that Deep Purple's songwriting chops have made a quantum leap in terms of composition, but scattered among the last half-dozen or so albums recorded and released primarily for the fanbase are signs of growth and maturity, particularly an emphasis on progressive rock that is not merely perfunctory.

For example, "Sometimes I Feel Like Screaming," a reflective ballad from Purpendicular that gave Gillan the chance to display a broad vocal range, lent the band some much-needed texture and dimension even if it is unlikely to make anyone forget Guns 'N Roses or Led Zeppelin, or to impress any Judas Priest fans who remained behind after that band exited the stage. Morse, too, got an opportunity to unleash some guitar harmonics in a decidedly non-metal context, prompting comparisons to his early influence, Jeff Beck.

Then it was Airey's turn to flash his expertise. A true heir to the late Jon Lord's prowess, Airey, occupying center stage surrounded by keyboards in his electronic laboratory, paid tribute to Deep Purple's de facto guiding voice with "Uncommon Man," the synthesizer-driven track from Now What?! inspired by Aaron Copland's celebrated 1942 "Fanfare for the Common Man," itself influenced by a wartime (World War Two) speech given by US Vice President Henry Wallace that proclaimed the dawning of a "Century of the Common Man."

But unlike its more celebrated contemporaries Black Sabbath or Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, through Lord's presence that has been perpetuated by Airey, has always had keyboards at the center of its compositional approach. (Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones was an accomplished keyboards player who found opportunities to roll them out when he could ("No Quarter," for example), although his pronounced influence on 1980's In Through the Out Door (Swan Song) found that band sounding like a heavy metal Steely Dan.)

And unlike the heated musical sparring between Lord and Blackmore during the early days, Airey, at least during the FivePoint show, dominated the proceedings with his keys, underscored by the prominent images of same displayed on the video monitors. Airey effected a segue from "Uncommon Man" to a lengthy intro into "Lazy," long a Lord showcase as well as being a centerpiece of Purple's live sets for four decades, which also gave Gillan, otherwise present only for the perfunctory lyrics, a chance to blow a little harmonica as part of the instrumental attack.

The keyboards-heavy emphasis did work to provide a lead-in to the punchy, Rainbow-esque "Knocking at Your Back Door," which, back in 1984, announced the return of the celebrated Mark II lineup and its Perfect Strangers (Mercury) album with a relative wham-bam-thank-you-ma'am, joining Lou Reed's "Walk on the Wild Side," ZZ Top's "Pearl Necklace," and a few others as examples of singles that managed to get descriptions of specific sexual acts onto the radio waves with hardly any protest about what the songs actually celebrated. After Airey indulged in some more extended stroking and fingering of his organ (ahem), the band revisited Perfect Strangers and its title song as prelude to its big finale.

Having already played three of the seven cuts on Machine Head, Deep Purple was hardly likely to leave without revisiting the pair of signature molten-metal tunes from that album. First came "Space Truckin'," the pounding side-closer that in the early days served as a springboard for extended instrumental excursions, which, as on Made in Japan, brought the band closer to progressive rock.

Which is a shame, because listening to (and singing along with) the lyrics reminded me of how silly they are, deliberately so, as this song isn't a considered rumination about our place in the cosmos—it's about banging your head like a hippie space cadet. And while it would still be intriguing to see how Airey and Morse would have soloed as Lord and Blackmore had done, it was not to be this time around. Besides, there was one more song that we haven't mentioned yet . . .

Indeed, once the deathless riff that kicks off "Smoke on the Water" burst from Morse's guitar, Deep Purple once again asserted its place in the hard-rock cosmos. However, in contrast to that simple riff, "Smoke" does tell a fairly involved story, a true-life tale of how the Montreux Casino in Switzerland, where the band was supposed to record Machine Head, had been destroyed in a fire that broke out during a Frank Zappa concert, thus cementing a rock legend more effectively than any segment of VH-1's Behind the Scenes could ever do.

With Ian Paice's (left, behind drum kit) health an issue now, is this the final farewell from Britmetal legend Deep Purple?

But like Judas Priest, Deep Purple didn't make the pretense of going offstage only to be called back by the by-now obligatory beseeching cheers of the faithful for an encore. The band simply waited a few moments before launching into it. I had glanced at my watch as "Smoke on the Water" was wrapping up. It was about five minutes to eleven, and I knew that Irvine, California, was about to shut down for the night. Curfew time.

Accordingly, the band vamped for just a few bars of "Time Is Tight"—typically, the vamp music is another Booker T. and the MGs gem, "Green Onions," but this one wryly confirmed that the band knew it had to vamoose. I told Kathie to get ready for "Black Night," but Purple instead launched into its other encore staple, "Hush," completing this relatively brief if somewhat representative survey of its half-century catalog by reprising its first-ever hit.

Encore

And that was it. Up came the house lights, and then the trek to remember where we parked the car. Walking through the parking lot, I overheard a guy say, "I'm never gonna see Deep Purple again." I didn't stop to ask why—I didn't even get a glimpse of him to see if he was younger or older—but as we walked on I wondered what he meant. Had he seen Purple before? Was he a Judas Priest fan who had stuck around to check out what the other noise was about? Was he expecting a different kind of band based on, perhaps, fragmentary impressions? Did he expect something more now that Deep Purple was in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Deep Purple put on a good show. So did Judas Priest. Neither was a great show, but those days are behind both bands now, not just because any of the founding or veteran members of both bands are, as they say in their native Britain, "pensioners" who likely don't need to keep working. I don't think that either needs to stop working if each wants to continue.

Priest is promoting its latest album, and the quartet of tracks the band fired off displayed the same firepower as its classic songs; however, I'll have to leave it to the band's aficionados to determine whether those new cuts differ noticeably from the Priest formula; I couldn't detect it from what I heard. Unlike when I saw them four years ago, Deep Purple relied on songs from its 1970s glory period for most of its set even though it too had a recent album to promote. Still, Ian Gillan got engaged nearly from the get-go, which lent the band sustained energy that it lacked previously.

I thought that as the headliner, Deep Purple's set should have been longer. But that might be more a reflection of the concert experience as it seems to be playing out now, particularly for established bands: Keep the sets tightly structured, emphasize the canon, and above all stick to the allotted time.

Did Judas Priest help to make its case for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Yes. Did Deep Purple justify its inclusion in the Rock Hall? Yes. But then again, I don't think the bar needs to be as high as I used to think it needed to be, and, quite frankly, I don't think that it is that great an honor to be inducted. That isn't meant in terms of the butthurt fan who calls it the "Hall of Shame" or the "Hall of Lame" and thinks it's a "travesty" because his or her favorite artist has not been inducted yet. That's simply a throughput problem caused by gross administrative inefficiency more than it is a shortsighted or elitist "snub." And then because there are so many artists still to induct, is there really any distinction to being inducted?

In that respect, my thinking may have returned to my initial reaction when I first learned, more than twenty years ago, that there was such a thing as the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: "That's kind of cheesy, isn't it?" Which doesn't mean I won't be going to shows like Deep Purple and Judas Priest any longer. I will. Particularly if the price is right.

Comments powered by CComment