Index

American Coup

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although not discussed in alphabetical or chronological order below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Birth of a Nation (1915)

The Birth of a Nation (1915)

![]()

![]()

![]() Executive Action (1973)

Executive Action (1973)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Gabriel Over the White House (1933)

Gabriel Over the White House (1933)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() JFK (1991)

JFK (1991)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

![]()

![]() Parkland (2013)

Parkland (2013)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Seven Days in May (1964)

Seven Days in May (1964)

![]()

![]()

![]() Suddenly (1954)

Suddenly (1954)

![]()

![]()

![]() The Tall Target (1951)

The Tall Target (1951)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977)

Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977)

Although the United States prides itself on the peaceful transfer of power epitomized by the succession of the presidency, four US presidents—Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, and John Kennedy—have been assassinated while in office, forcing an immediate, involuntary transfer of power to the vice president.

Furthermore, the Electoral College, which is the body that actually elects the president—not the public voting directly—has elected presidents who did not receive the majority of the popular vote, more recently in 2000, which saw the Electoral College elect George W. Bush, and in 2016, when it elected Donald Trump—with Trump now insisting that it is up to him to decide whether he will leave office regardless of the 2020 election results.

And while it does not touch directly on that scenario, one of our movies in this section, which examines various scenarios in which a coup, or overthrow, of the American government could occur, touches on several of Trump's dictatorial tendencies—more than eight decades before he began to exhibit them.

The movies discussed below begin with examinations of two presidents, Lincoln and Kennedy, who were actually removed from office by assassination, before delving into various other fictitious scenarios that could disrupt or displace the peaceful manner of governance we were all taught in school, demonstrating that even the movies are not immune to "the paranoid style in American politics," to borrow the title of the famous 1964 essay by political scientist Richard Hofstadter.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Birth of a Nation (1915)

The Birth of a Nation (1915)

Directed by D.W. Griffith. Written by Griffith and Frank E. Woods, based on the novel The Clansman by Thomas Dixon, Jr.

Like Citizen Kane (discussed in the media section Pageantry and Personalities above), Griffith's sweeping, notorious The Birth of a Nation encompasses many threads; here, they are from before, during, and after the US Civil War, most of them affecting the Northern Stoneman family and the Southern Cameron family, friendly in the antebellum period but partisan during the war—and hostile when, after the war, abolitionist Congressman Austin Stoneman (Ralph Lewis), based on Thaddeus Stevens (portrayed by Tommy Lee Jones in Lincoln, from the Presidents and Pretenders to the Throne section above), brings his mulatto protégé Silas Lynch (George Seigmann) into the South to enfranchise freed slaves.

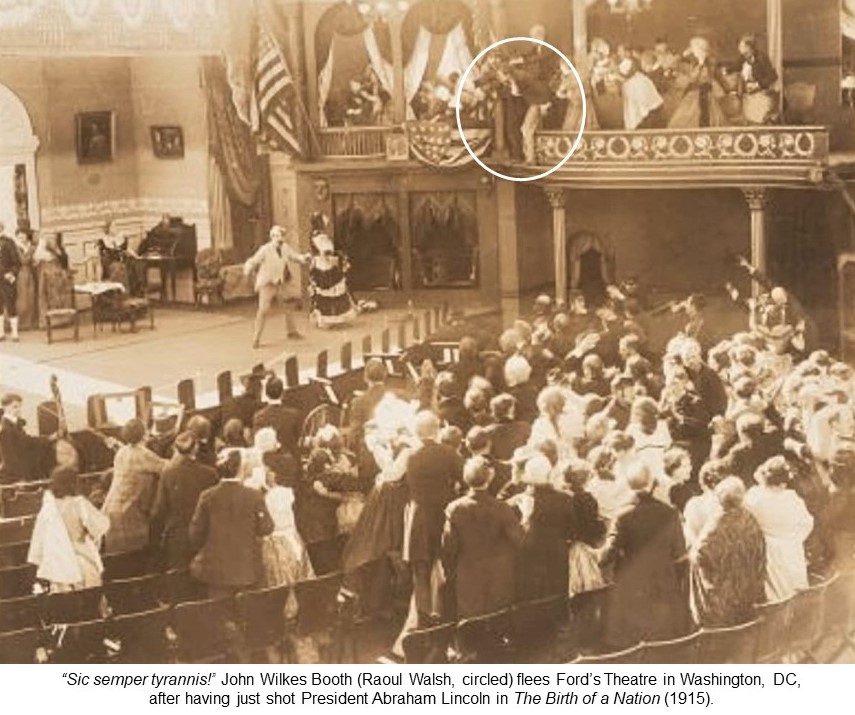

Thus, Abraham Lincoln (Joseph Henabery) is a background figure in Nation although of course Lincoln's policies dictate the events portrayed in this landmark silent-movie saga. However, depiction of his April 14, 1865, assassination at Ford's Theatre in Washington, DC, marks the climax of the first half of Nation, conveyed dramatically as Lincoln is shot by Southerner John Wilkes Booth (Raoul Walsh, later to become a notable director), who then escapes by leaping from the theater balcony onto the stage while shouting (silently, of course) "sic semper tyrannis!" ("thus always to tyrants").

However, like much of The Birth of a Nation, the accuracy of these events is subject to dramatic license—as indeed is the historical revisionism of the movie overall, which paints Southern whites as victims of black and Northern oppression after the war, thus justifying the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the defense of the "Aryan birthright" (as one intertitle puts it). In any case, the dramatic depiction of Lincoln's assassination and Booth's escape remains an iconic scene in the history of cinema.

![]()

![]()

![]() The Tall Target (1951)

The Tall Target (1951)

Directed by Anthony Mann. Written by Art Cohn and George Worthing Yates, based on a story by Yates and Daniel Mainwaring.

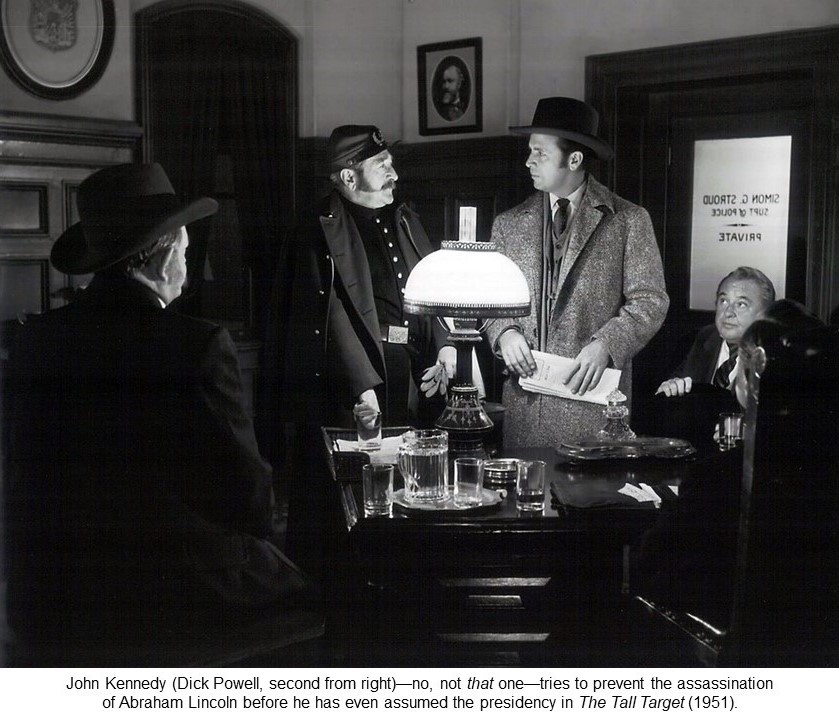

But prior to Lincoln's actual 1865 assassination, he was the subject of an attempted assassination even before he officially became president as the reputed "Baltimore Plot" pegged him as The Tall Target to be killed in late February 1861, just ahead of his March inauguration, itself followed by the start of the Civil War in April. And by a curious coincidence, a New York police superintendent named John Kennedy became involved in trying to thwart the plot although in retrospect it could make for a warped if intriguing time-travel story to have the John Kennedy involved in some capacity.

For our purposes here, though, we have John Kennedy (Dick Powell), now a police sergeant, trying in vain to warn his superintendent about an assassination attempt on Lincoln, then surrendering his badge and boarding a Baltimore-bound train in New York to take action on his own. Although he discovers his colleague, already aboard, has been murdered, Kennedy gains a seeming ally in militia Colonel Caleb Jeffers (Adolphe Menjou), but Kennedy soon discovers that Jeffers is part of the conspiracy that includes West Point sharpshooter Lance Beaufort (Marshall Thompson) and his sister Ginny (Paula Raymond) as he's cut off from help with the conspirators closing in on him—and on Lincoln. Amidst period sets of train interiors and railway stations given a tense film noir atmosphere, smooth, confident Powell negotiates his evasions and persuasions as sometimes-heated talk about the incoming president and the possibility of war swirls fitfully in a rendezvous with The Tall Target.

![]()

![]()

![]() Executive Action (1973)

Executive Action (1973)

Directed by David Miller. Written by Dalton Trumbo, based on research by Donald Freed and Mark Lane.

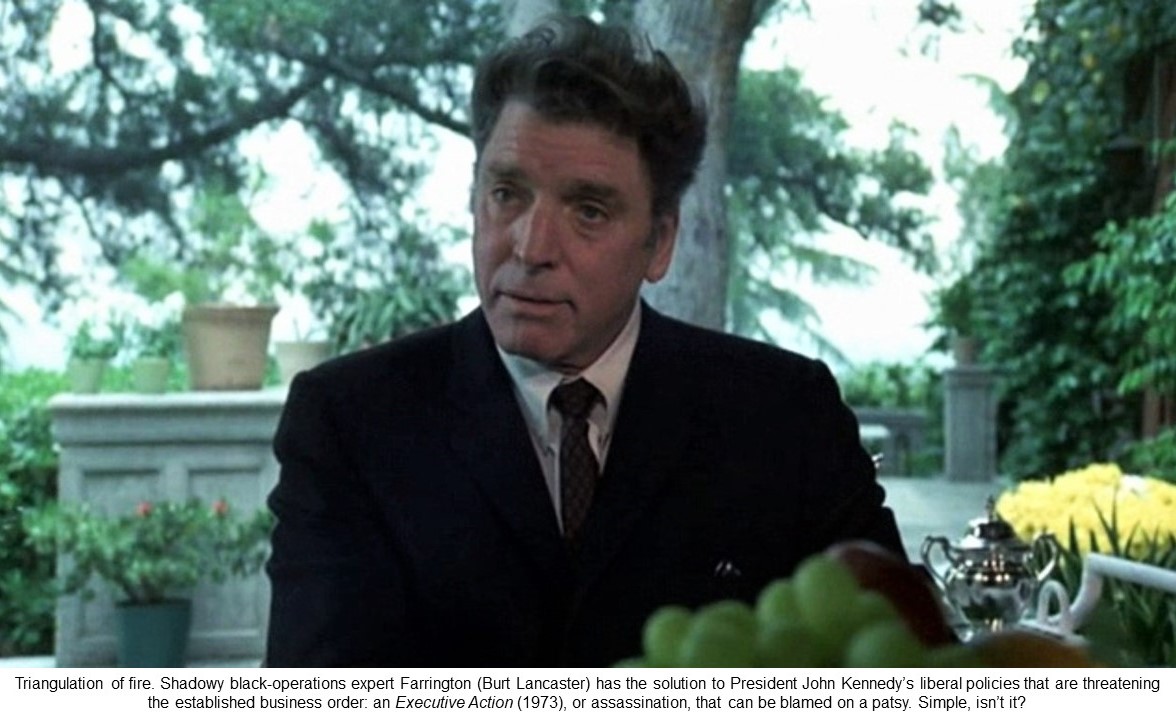

Two decades before Oliver Stone's JFK posited a conspiracy theory in the John Kennedy assassination, Executive Action presented its story of a businessmen's cabal that plotted to kill the president and frame a patsy, Lee Harvey Oswald, as the lone gunman. Trumbo's lean script, based partly on Rush to Judgment, Lane's early critique of the Warren Commission's conclusions, keeps the storyline simple while the film's modest budget, coupled to Miller's journeyman direction, gives Executive Action a mundane feel that greatly underwhelms the subject matter's momentousness.

Yet the film's very laconic matter-of-factness lends plausibility to its conspiracy theory by avoiding grandiosity. As a clutch of businessmen led by Foster (Robert Ryan) tries to convince influential oilman Ferguson (Will Geer) to support an "executive action," or assassination, against President Kennedy in response to his liberal policies that threaten the established order they all represent, shadowy black-operations expert Farrington (Burt Lancaster) posits that a "triangulation of fire" shooting that his teams are already practicing will right the situation. When Ferguson finally agrees, the operation begins in earnest for the hit in Dallas's Dealey Plaza with three shooters positioned strategically for the kill.

Editor George Grenville maximizes the use of archival Kennedy footage, particularly during the shooting, to present the contrast to the live action, while the vaguely ominous conclusion to Executive Action suggests a more sinister conspiracy than that told by its modest story. Paging Oliver Stone? (And don't think we've seen the last of Burt Lancaster, either. Far from it.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() JFK (1991)

JFK (1991)

Directed by Oliver Stone. Written by Stone and Zachary Sklar, based on the books On the Trail of the Assassins by Jim Garrison and Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy by Jim Marrs.

Two decades later, Stone, armed with an A-list budget and an all-star cast, did produce a grandiose version of the John Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory; in fact, Stone and Sklar develop JFK into an assassination-theory omnibus that augments the actual investigation of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) with other elements, thus fashioning an expansive myth to explain the greatest unsolved crime of 20th-century America.

Probing possible New Orleans ties to accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald (Gary Oldman), including the curious David Ferrie (Joe Pesci), right after the assassination, Garrison finds nothing initially but returns three years later when he suspects prominent businessman Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones) of being a conspirator. Then Garrison meets with a mysterious government operative (Donald Sutherland), who unfurls a grand conspiracy involving the CIA, the Mafia, the military, and Vice President Lyndon Johnson, with its goal of preventing JFK's putative withdrawal from Vietnam.

Despite its complex framework of players and events, JFK maintains focus thanks to Oscar-winning cinematography by Robert Richardson and editing by Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia. Costner is bland but believable as the crusader leading his staff (which includes Laurie Metcalf, Michael Rooker, and Jay O. Sanders), although Pesci, still in Goodfellas mode, chews scenery, and Sissy Spacek, never lovelier, is saddled with playing Garrison's shrewish wife. JFK has cinematic flaws beyond its polarizing conclusions, but it remains compelling and provocative moviemaking that injects enough reasonable doubt into the Big Daddy of conspiracy theories that still sparks heated debate decades after the fact.

![]()

![]() Parkland (2013)

Parkland (2013)

Written and directed by Peter Landesman, based on the book Four Days in November: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy by Vincent Bugliosi.

Balancing the JFK conspiracy theories is Parkland, with Landesman using Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas as the touchstone for his rushed, scattershot study of the ripple effect immediately following John Kennedy's assassination while using Bugliosi's exhaustive defense of the Warren Commission's conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin to reinforce that position even as it plays coy with other aspects of the event.

Personifying those events are key figures including Dr. Charles Carrico (Zac Efron), the first emergency-room physician to attend to Kennedy; Secret Service head Forrest Sorrels (Billy Bob Thornton), who assesses responsibility for the shooting—especially his own; local businessman Abraham Zapruder (Paul Giamatti), who is besieged once word escapes that he managed to film the shooting in progress; and FBI agent James Hosty (Ron Livingston), who realizes that his prior interaction with Oswald is another kind of smoking gun—one that indicts the Bureau. Meanwhile, Oswald's scheming mother Marguerite (Jacki Weaver) claims he was a government agent as sober Robert (James Badge Dale) berates younger brother Lee (Jeremy Strong) for his actions during a brief jail visit.

What ultimately sinks Parkland is a sprawling cast scrambling to inject keynote incidents into an intensively scrutinized historical narrative, with no one establishing more than rudimentary dimension as Landesman's sole direction to his cast seems to have been to deliver angry outbursts, then leaven them with pensive stares; only Giamatti manages much depth as the anguished bystander thrust into immortality—but only fleeting peeks at his famous home movie betrays Parkland's refusal to take any meaningful stand on the assassination.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Gabriel Over the White House (1933)

Gabriel Over the White House (1933)

Directed by Gregory La Cava. Written by Carey Wilson, adapted from the novel Rinehard: A Melodrama of the 1930s by Thomas Tweed.

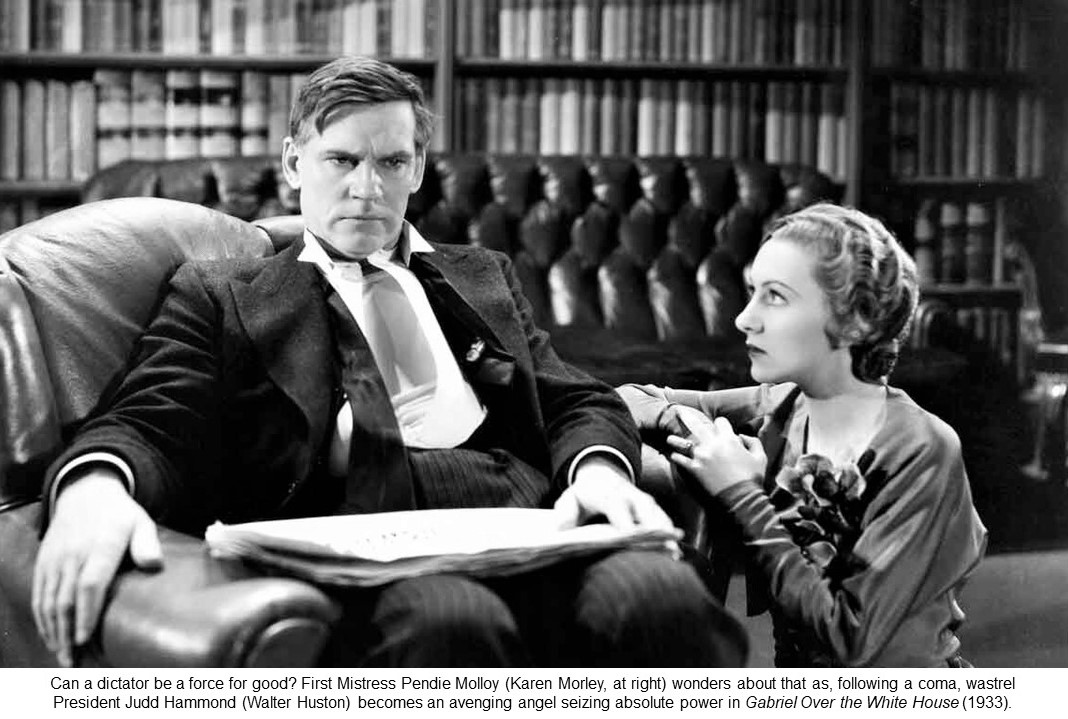

What if Jeffersonian democracy—"the greatest good for the greatest number"—arose through dictatorship? Gabriel Over the White House explores this fascinating premise, realized during the tumult of the Great Depression, with a simple, direct impact that leaves a profoundly mixed impression while the suggestion of divine intervention only makes this political fantasy even more bizarre.

Newly-elected President Judd Hammond (Walter Huston) is the Party's man, contemptuous of the press, dismissive of the day's critical issues—unemployment, homelessness, poverty, racketeering spawned by Prohibition, and growing social unrest—and eager to install his young mistress Pendie Molloy (Karen Morley) in the White House. (Amazing to think that they anticipated a Donald Trump even back then.) But when he lapses into a coma after a self-inflicted auto accident, he awakes as a crusader determined to rectify those issues.

Hammond, who Pendie speculates to presidential secretary "Beek" Beekman (Franchot Tone) might be possessed by the Archangel Gabriel, fires his cabinet, coerces Congress to adjourn indefinitely, and declares martial law, vowing to right these injustices. Thus the conundrum: Can a dictator be a force for good? Italy's Benito Mussolini claimed to have made the trains run on time, and Gabriel portrays Hammond as sincere but ruthless in his quest to right all wrongs. La Cava guides Wilson's brazen, hardly-subtle script with efficiency and delicacy, softening Huston's fascistic edges as they carry Gabriel Over the White House.

![]()

![]()

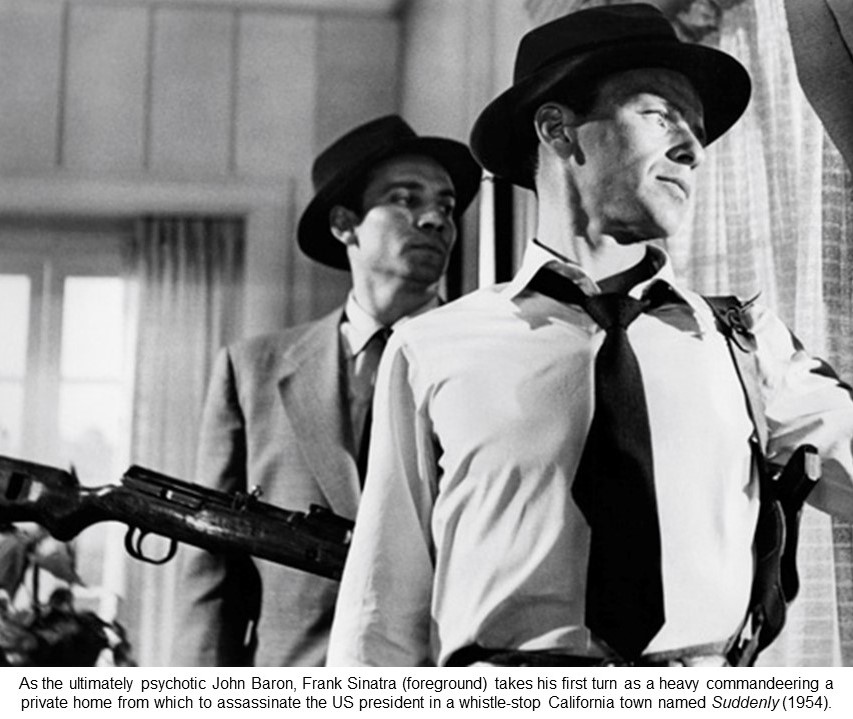

![]() Suddenly (1954)

Suddenly (1954)

Directed by Lewis Allen. Written by Richard Sale, adapted from his story "Active Duty."

The attempted assassination of the American president thrusts assassins and victims of circumstance into a tense crucible in Suddenly, which is the (fictitious) name of the California town about to host the president in this taut if contrived tale. Sale's script packs both melodrama and psychology into a parlor tale heightened by Allen's efficient, economical pacing that sidesteps all political ramifications while proffering a telegraphed narrative that carefully ties up its loose ends. Tipped to the president's arrival, Sheriff Tod Shaw (Sterling Hayden) is informed of the assassination attempt by Secret Service agent Dan Carney (Willis Bouchey) while John Baron (Frank Sinatra) and his two cronies (Christopher Dark, Paul Frees) also arrive in Suddenly, masquerading as FBI agents.

Visiting Pop Benson's (James Gleason) house opposite the train station, they warn that assassins could find it an advantageous location—then prove to be those assassins when Shaw and Carney also investigate the house and encounter Baron's gang as Suddenly hunkers down for the climax. Benson's grandson Pidge (Kim Charney) and daughter-in-law Ellen (Nancy Gates) are also in the house, with Pidge's handgun a convenient happenstance emblematic of Sale's unsubtle manipulation and transparent moralizing. In his first dramatic role, Sinatra, his Baron inevitably revealed to be a homicidal psychopath trained in the military, delivers a quietly chilling performance as Suddenly hits its narrative targets but misses the artistic bullseye.

(Following John Kennedy's 1963 assassination, Sinatra, a Kennedy supporter, tried to have Suddenly pulled from circulation based on the rumor that Lee Harvey Oswald had seen the movie just prior to the assassination.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

Directed by John Frankenheimer. Written by George Axelrod, adapted from the eponymous novel by Richard Condon.

Frank Sinatra returns in another assassination-themed political thriller, but this time his character is trying to prevent an assassin from acting in The Manchurian Candidate, which pushes Cold War paranoia to a chilling peak as a brainwashed assassin becomes the deadly tool for a communist takeover of the United States unless he can be stopped. Axelrod retains elements of Condon's droll, biting, absurdist humor while Frankenheimer's direction stresses the tension and quiet lethality swirling within Laurence Harvey, whose impassive yet unsettling portrayal of American soldier Raymond Shaw trumps first-billed Sinatra's performance—although Angela Lansbury almost tops them both in less screen time.

During the Korean War, Shaw, awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for saving his platoon, had actually been captured, brainwashed in communist Manchuria, and returned to the States as a programmed assassin for his American-based handlers. Shaw's commanding officer Ben Marco (Sinatra) was also captured, and he begins to investigate Shaw, whose mother Eleanor (Lansbury) is the puppet master to Shaw's stepfather, Senator Johnny Iselin (James Gregory), a Joseph McCarthyesque buffoon whose allegations of communists in the Defense Department give him new political life—and disguise the nefarious communist plot.

Lansbury's perfidy and incestuous insinuation is doled out in glorious degrees while Janet Leigh, as Marco's love interest, has a meet-strange with Marco aboard a train is a marvel of non sequitur; meanwhile, the climax in Madison Square Garden became a template for assassination thrillers. After watching The Manchurian Candidate, you might think twice about playing solitaire ever again.

![]()

![]()

![]()

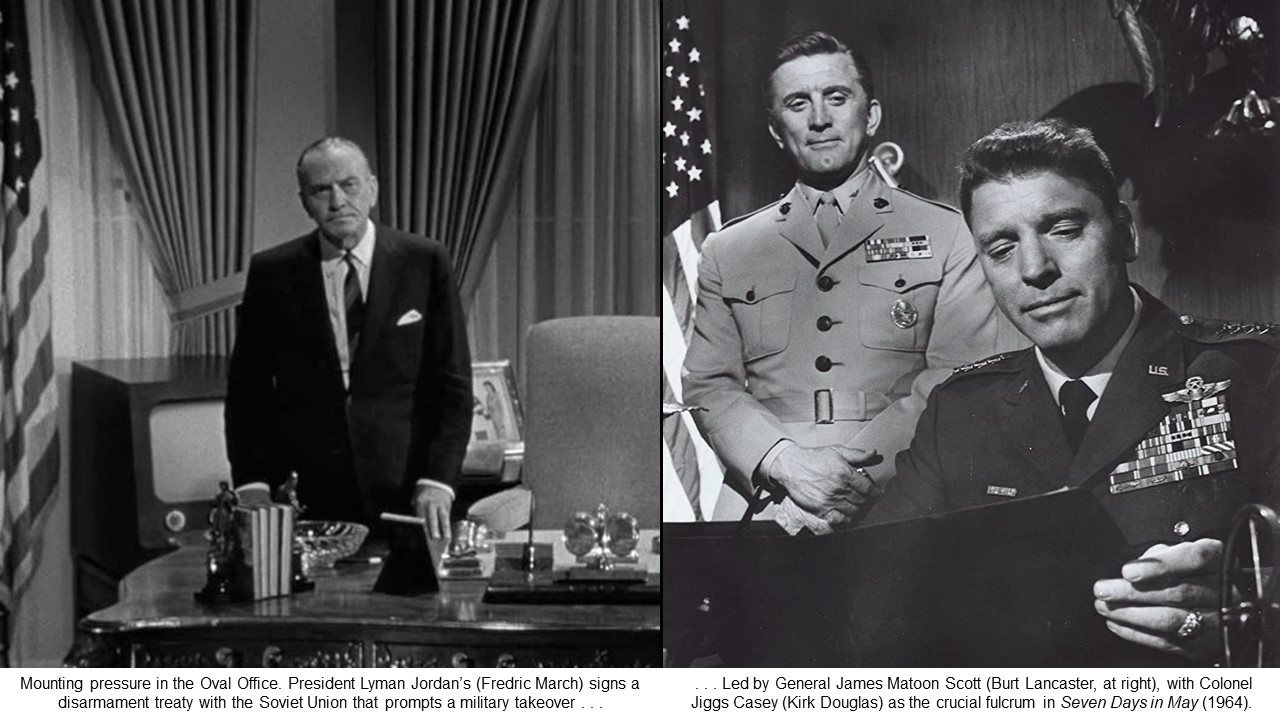

![]() Seven Days in May (1964)

Seven Days in May (1964)

Directed by John Frankenheimer. Written by Rod Serling, adapted from the eponymous novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II.

Burt Lancaster returns to intrigue and conspiracy as hawks and doves collide with the fate of the United States in jeopardy in Seven Days in May, a Cold War political thriller centered on a military coup poised to usurp power from President Lyman Jordan (Fredric March) over his signing a disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. Serling's adaptation focuses on the players and their often-tense interactions, which results in a number of fine performances, particularly by Lancaster, whose General James Matoon Scott, Lyman's Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, spearheads the putative junta, and by Kirk Douglas, who as Scott's aide Colonel "Jiggs" Casey is the crucial fulcrum.

With his popularity sagging because of the treaty, Lyman receives more distressing news from Casey: a mysterious Army unit called ECOMCON plans to seize communications as Scott, seemingly grooming himself for public office as a right-winger, takes control of the government on a specific date in May. Shocked but convinced, Lyman assembles a team to investigate and neutralize the threat as the clock ticks toward the confrontation. Back at the helm of a smart thriller, Frankenheimer generates suspense through cinematographer Ellsworth Fredericks's distinctive shot framing as Jerry Goldsmith's martial-like score ratchets the tension. March is reliably strong but Lancaster, resisting the temptation to play the ideologue, is ultimately impressive, especially during his showdown with March. Not subtle but nevertheless compelling, Seven Days in May imparts a still-timely warning.

![]()

![]()

![]()

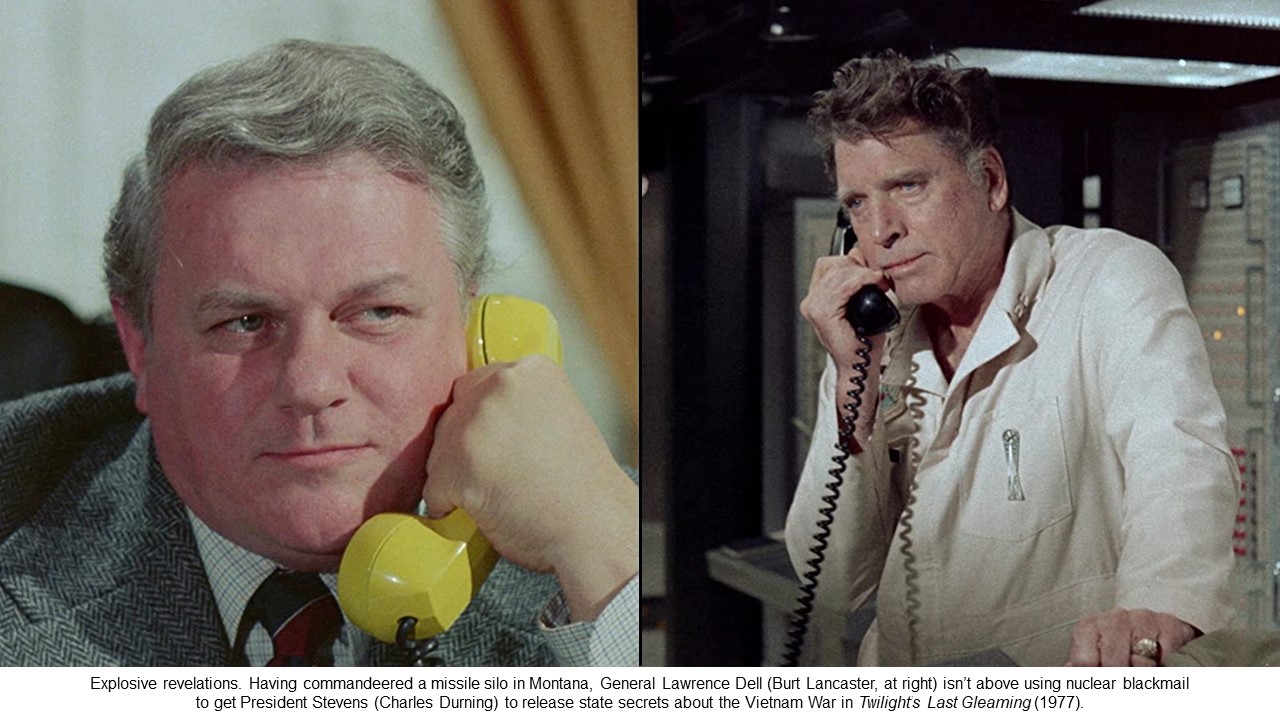

![]() Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977)

Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977)

Directed by Robert Aldrich. Written by Ronald Cohen and Edward Huebsch, adapted from the novel Viper Three by Walter Wager.

In case (like me) you can't get enough of Burt Lancaster in edgy political thrillers, he is back again in Twilight's Last Gleaming as General Lawrence Dell, a Vietnam veteran railroaded into prison on a murder charge because of his uncomfortable insistence on revealing ugly truths about that war. Leading a team of escaped military prisoners, he commandeers a Montana nuclear-missile silo. Dell's demand? That President Stevens (Charles Durning) make public a classified National Security Council document that explains why the United States continued to fight a war it knew it couldn't win—and Dell is prepared to use nuclear blackmail to back up his demand.

Indeed, for that reason alone, Twilight's Last Gleaming stands as one of the best Vietnam movies: Compared to most Vietnam movies that never rise above squad-level comprehension, it is practically alone in articulating America's geopolitical impetus vis-à-vis the war. To be sure, this military political thriller is overlong and occasionally fallow, and Aldrich's liberal use of split-screens not only seems quaint but, along with Jerry Goldsmith's urgent score, reeks of made-for-television movies, while the bursts of danger, including a commando raid on the silo, are pro forma action moves.

The real excitement is the callous realpolitik played out by Stevens's cabinet staffed by Joseph Cotten, Melvyn Douglas, and William Marshall, with Richard Widmark as a correspondingly cutthroat general—and when Dell insists that Stevens journey to Montana to ensure the hijackers' safe passage, Stevens realizes that not even he is indispensable. Suggesting his appearance in Seven Days in May, Lancaster is effective but subdued, while Durning supplies the plainspoken humanity in Twilight's Last Gleaming.

It Can't Happen Here?

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although not discussed in alphabetical or chronological order below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

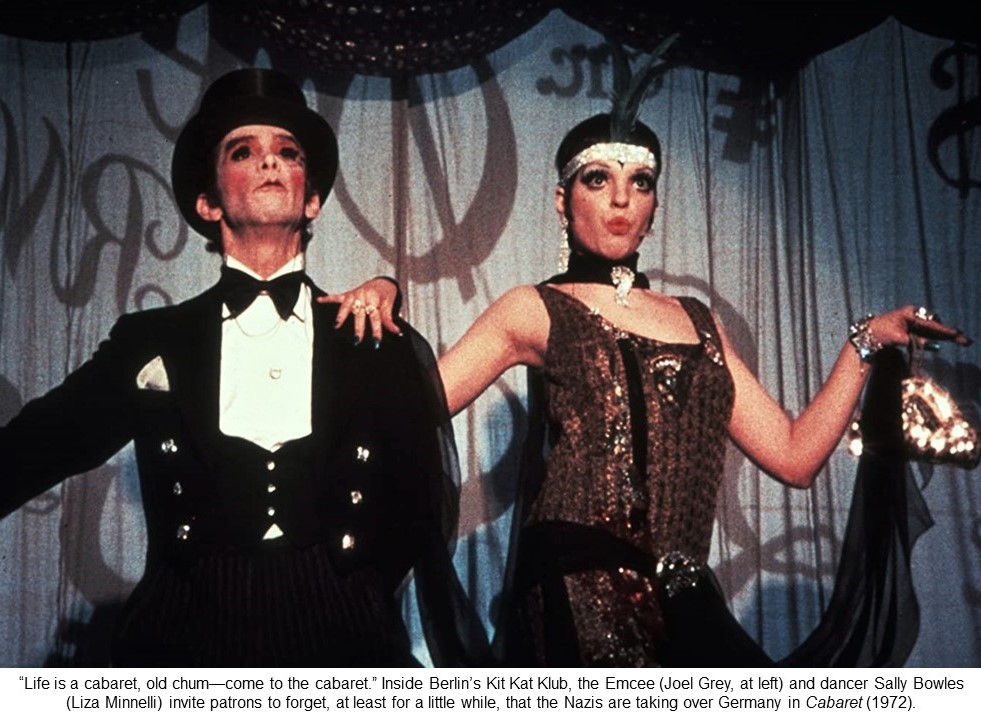

![]() Cabaret (1972)

Cabaret (1972)

![]()

![]()

![]()

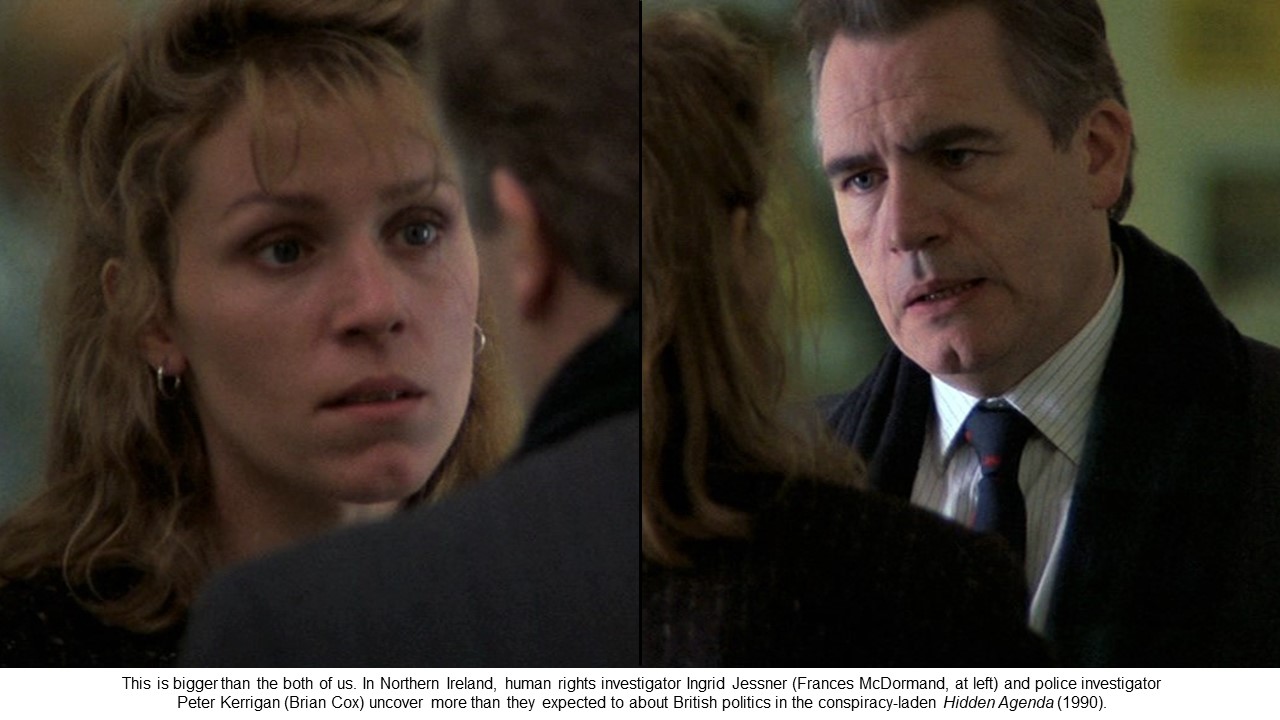

![]() Hidden Agenda (1990)

Hidden Agenda (1990)

![]()

![]()

![]()

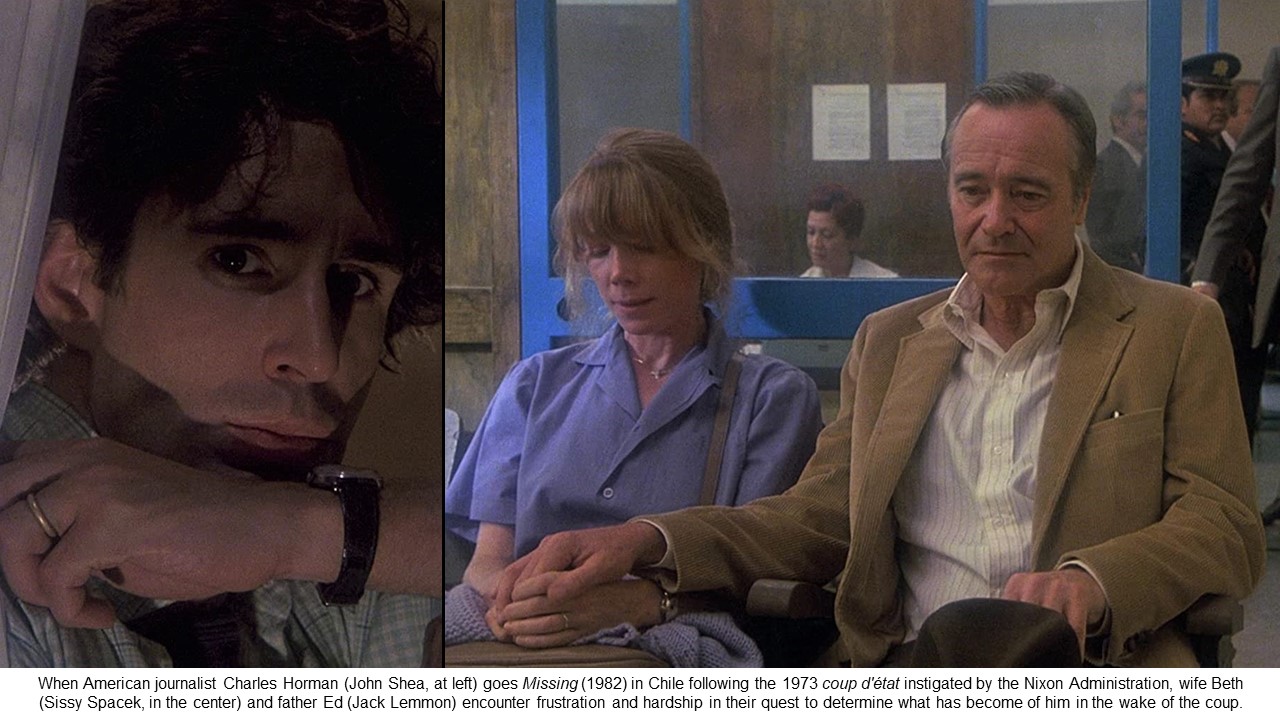

![]() Missing (1982)

Missing (1982)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

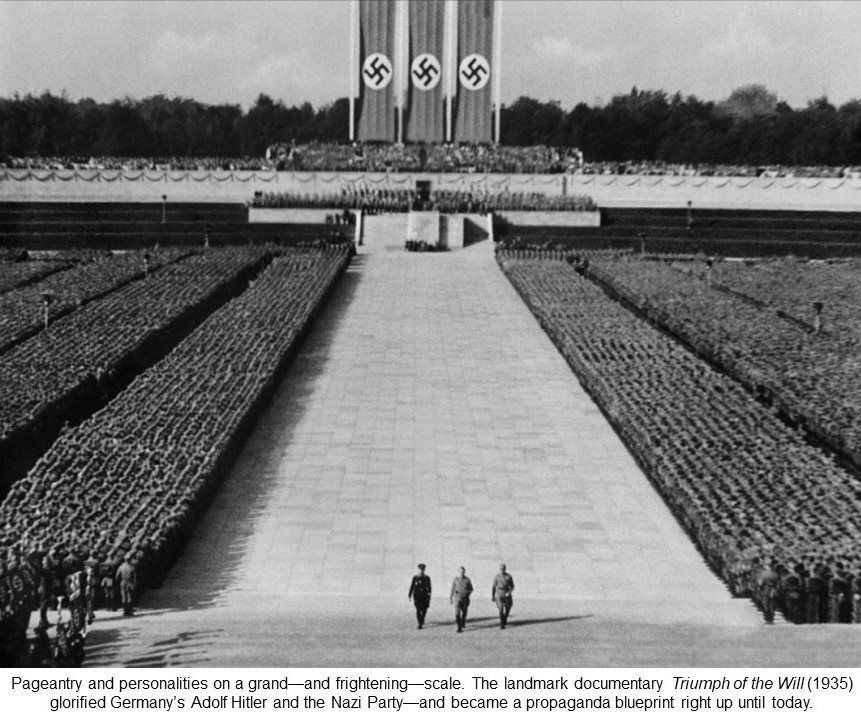

![]() Triumph of the Will (1935)

Triumph of the Will (1935)

![]()

![]()

![]()

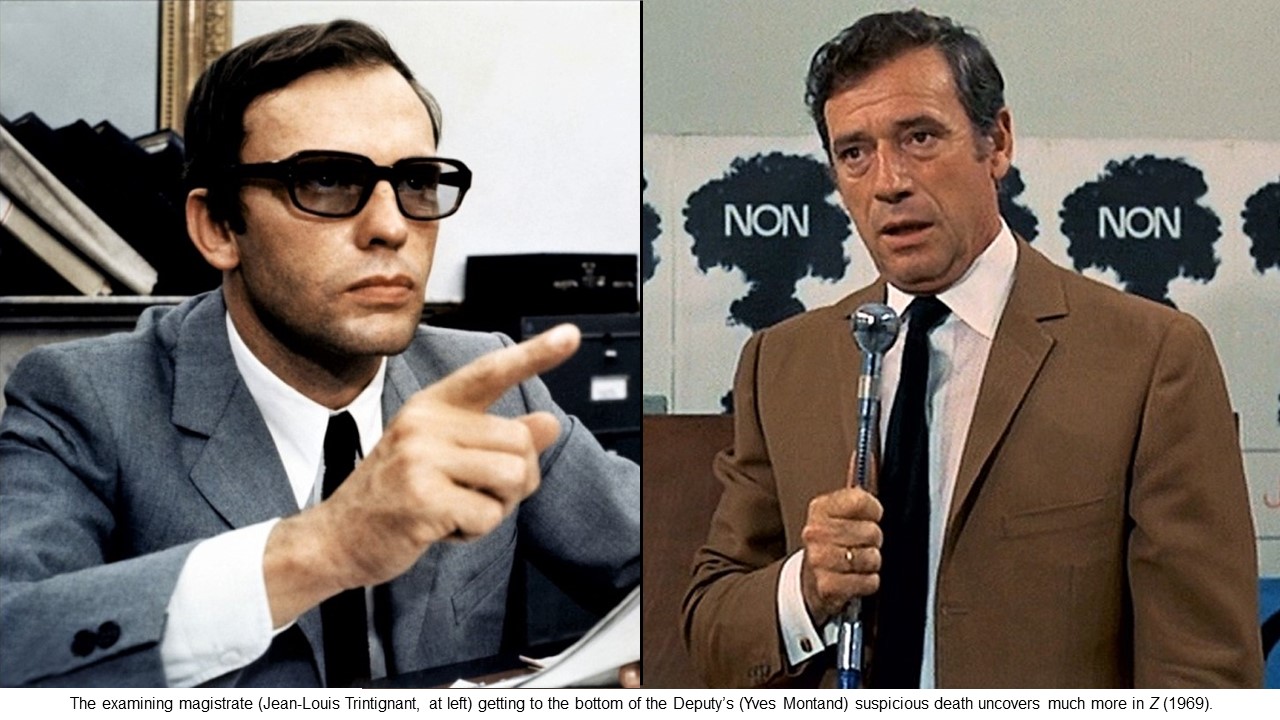

![]() Z (1969)

Z (1969)

The American Coup section above presents ample examples of American political paranoia, but assassinations, overthrow, revolt, and other abrupt, usually violent means of seizing power are known throughout the world and have been for centuries.

This section offers just a taste of movies from or about other countries that have, or could have, experienced the kind of coups described previously. They are chosen because they contain elements that can be easily repeated in an American context—if they have not been so already.

We begin with the signature example of repressive, totalitarian terror, Nazi Germany, before touching on the fascist turn Greece experienced in the late 1960s, a similar right-wing turn—aided by the United States—in Chile, and a fictitious scenario in Great Britain rooted in actual events.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Triumph of the Will (1935)

Triumph of the Will (1935)

Directed by Leni Riefenstahl. Written by Riefenstahl, Walter Ruttmann, and Eberhard Taubert.

The only documentary discussed in this voters' guide, I included Triumph of the Will because of its enduring influence on both documentary and feature movies and because so much of its imagery and iconography has been repeated so often not just on film but also in real life. Indeed, Leni Riefenstahl's landmark documentary, which introduced many modern cinematic techniques, is a spectacular pageant that lionizes Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party not long after their 1933 rise to power. Filmed at the 1934 Nuremburg rally, Triumph portrays the thrilling parades and formations, the passionate oratory, and the adoring throngs all designed to paint the Nazis as Germany's savior and unifying force.

Ignoring the brutal tactics that paved the Nazis' rise, Riefenstahl creates a hagiography replete with impressionistic shots, sweeping pans, and stirring music to create probably the most (in)famous propaganda film of all time. In the fair faces of the phalanxes of the Hitler Youth and Labor Service ranks lay the incipient blitzkrieg machine, glimpsed later in the form of the fearsome Schutzstaffel (SS) marching through Nuremburg.

Meanwhile, Hitler's speeches stress the strength of the people that buttresses the party and the state—as much courting as exhorting, although the adoration showered on Hitler, lovingly framed by Riefenstahl, defines the führerprinzip (leader principle) that drove the Third Reich. Triumph's legacy perpetuated itself in columns of tanks rumbling past the Kremlin's Communist leaders, and in an American president preaching relentlessly to his base about how only he can tell them the truth about the dangers they face from socialists, Democrats, antifa, and fake news, the "enemy of the people," reinforcing the power of media to shape perception as politics regardless of ideology.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Cabaret (1972)

Cabaret (1972)

Directed by Bob Fosse. Written by Jay Allen, based on the book Cabaret by Joe Masteroff, the play I Am a Camera by John Van Druten, and the novel Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood.

Before the Nazis came to power in Germany, its Weimar Republic was a liberal democracy with overtones of risqué attitudes, and Fosse's dynamic, outré musical drama Cabaret, set in 1931 Berlin, conveys this bold juxtaposition of casual decadence and incipient menace with a frisson that transcends the trivial concerns of its principal characters. They include Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli), an American entertainer at Berlin's Kit Kat Klub looking for love and a career break, and Brian Roberts (Michael York), an Englishman in Berlin to complete his German studies while working as an English tutor who becomes Sally's friend and, eventually, lover.

Amidst Germany's social sea-change, the Kit Kat Klub promises refuge within its seedy walls, where the leering, luridly compelling Emcee's (Joel Grey) exhortations border on demonic and the musical numbers (John Kander and Fred Ebb's "Wilkommen," "Cabaret," and "Mein Herr") border on salacious thanks to Fosse's sizzling choreography, respites from growing unrest that threatens Brian's student Fritz Wendel (Fritz Wepper), who has fallen for another of Brian's students, Jewish department-store heiress Natalia Landauer (Marissa Berenson).

Yet that unrest cannot help but seep in, reflected in the Emcee's pointed observation "If You Could See Her (The Gorilla Song)," professing his love for a Jewish woman while depicting her as Untermensch (subhuman), and especially in the fascistic beer-garden rouser "Tomorrow Belongs to Me" that marks Cabaret's chilling pivot point. Grey and Minnelli are both tremendous as Cabaret, even tamed from its darker, growling stage version, remains a feast for the senses, adroitly combining its musical numbers with its character sketches and historic backdrops into riveting, thoughtful, and at times unsettling entertainment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Z (1969)

Z (1969)

Directed by Constantin Costa-Gavras. Written by Costa-Gavras and Jorge Semprún, based on the novel Z by Vassilis Vassilikos.

Brash and blunt if sometimes sketchy and diffuse, Z gains power as it relates in docudrama form the events that led to the 1967 right-wing coup d'état in Greece that established a dictatorship by military junta, which banned many political and cultural elements including the letter Z, whose then-contemporary Greek meaning was "he lives." The flashpoint is the 1963 assassination of leftist politician Grigoris Lambrakis (Yves Montand, although simply referred to "the Deputy"), struck down in a vehicular attack during a peace-and-nuclear-disarmament rally that launches the investigation into his assault and its revelations that form the heart of Z.

Costa-Gavras brooks no subtlety: The disclaimer in the opening credits asserts that resemblances to actual persons are intentional before the government's security chief (Pierre Dux) lectures government ministers on the dangers of leftist "mildew" infecting the political mind. When the Deputy's autopsy findings contradict the official story of a drunk-driver hit-and-run, the examining magistrate's (Jean-Louis Trintignant) investigation eventually uncovers the right-wing organization behind the assassination—and the high-level assistance it received—although the seeming victory proves tragically Pyrrhic. Broadness creeps into a few of the performances, and Costa-Gavras prompts disorientation with abrupt flashbacks, but with Mikis Theodorakis's evocative, if occasionally incongruous, score, Z becomes an ultimately chilling political thriller.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Missing (1982)

Missing (1982)

Directed by Constantin Costa-Gavras. Written by Costa-Gavras and Donald E. Stewart, based on the eponymous book by Thomas Hauser.

Costa-Gavras returns to examine the 1973 coup d'état in Chile that overthrew the left-wing government led by socialist President Salvador Allende and installed a military junta led by fascist General Augusto Pinochet, a coup that was facilitated by the Nixon Administration in response to Allende's campaign to nationalize Chilean industries monopolized by American companies. This comes as a shock to Ed Horman (Jack Lemmon), the archetypal conservative Middle American who learns that his son, idealistic journalist Charles (John Shea), goes Missing in the coup's quietly terrifying aftermath as dissidents foreign and domestic are rounded up in this chilling story based on Hauser's true account of Charles Horman's disappearance.

Journeying to Chile—although, curiously, Costa-Gavras never makes that explicit despite the obvious signposts—Ed joins Charles's wife Beth (Sissy Spacek) in the search for Charles, who had inadvertently learned of American involvement in the coup, and gets a bracing lesson in Chilean and American deception and duplicity as Costa-Gavras weaves incisive institutional machinations with perceptive interpersonal dynamics to produce a hard-hitting political film with substantial emotional impact. Missing profiles Ed's rude introduction to realpolitik as he and Beth pursue false leads and dead ends while receiving slick reassurances from American officials, all while stumbling toward an answer to Charles's disappearance.

Lemmon is compelling if perhaps too mannered, but Spacek, challenged to transcend potentially an accessory role, matches him step for step; their chemistry, rarely overdone, is at the heart of Missing. Meanwhile, Costa-Gavras creates an atmosphere of veiled yet palpable deceit and dread—punctuated by periodic gunfire that shatters the feigned civility—while using effective flashback techniques to backlight the engrossing narrative that make Missing an intelligent political thriller that doesn't ignore the personal turmoil that makes it relevant.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Hidden Agenda (1990)

Hidden Agenda (1990)

Directed by Ken Loach. Written by Jim Allen.

Beginning as a compact political thriller based partly on actual events during "the Troubles" in Northern Ireland, Hidden Agenda takes a final turn into far-fetched conspiracy territory, but up until then it maintains a taut focus centered on human rights investigator Ingrid Jessner (Frances McDormand) and British police investigator Peter Kerrigan (Brian Cox) as they chase leads, witnesses, and dead ends trying to learn more about the killing of Paul Sullivan (Brad Dourif), an American human rights lawyer and Ingrid's lover killed by operatives of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), in a manner reminiscent of Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek in Missing; indeed, Jessner alludes to the human rights commission's work in Chile.

Sullivan was killed while en route to meet with an ex-army intelligence officer (Maurice Roëves) who claimed to have explosive evidence about Margaret Thatcher's rise to power. The RUC's initial story blaming the killings on the Irish Republican Army dissolves in the glare of international publicity, prompting the British government to send Kerrigan to investigate. Cox then becomes the center of Hidden Agenda as his Kerrigan zeroes in on the evidence Sullivan pursued, discovering indications of a right-wing coup that usurped control of the British Labour government, which then leads to Kerrigan's crisis of conscience.

Unlike American political films, which tend to baste their subject matter in exaggerated melodrama or sentimentality, Loach's effort delivers a sure and economical narrative that is easy to follow even for viewers not familiar with events in Northern Ireland, ensuring that Hidden Agenda maintains its intelligence and sobriety without abandoning its storytelling interest.

Comments powered by CComment