Index

What an absolutely insane year 2020 has been—and it's not even over yet. In particular, the United States has a general election upcoming in November, and not only has that already proved to be insane—it could go positively psychotic.

This is a pop-culture site, so don't worry, we'll not go into polemics that will raise your blood pressure faster than you can say "fake news." In fact, this "Voters' Guide to Presidential Movies" is meant to offer a respite from the frenzy while keeping to the topic of politics in general and presidential politics in particular. Below you'll find summaries of an array of movies from old to new that have thrown their hats into the ring of political discourse, with an emphasis on the US presidency although that is not exclusive.

Indeed, to touch on the various moods politics and presidents evoke, I've grouped these movies around different themes, keeping in mind that several of these movies could fit under more than one theme; I've grouped those under the theme that reflects that part of the movie I think is most pertinent overall.

For instance, The Front Runner is about Gary Hart's abortive 1988 presidential run, but since it was a media-driven scandal that forced his withdrawal from the race, it appears under the media theme rather than the campaign-trail theme. Of course, politics does encompass a multitude of personal and social aspects, and many of these movies reflect several of those aspects to varying degrees. I've also included a few movies that don't seem to touch on politics or presidents at all, at least not overtly or literally, but are analogous to our subject.

To hold office, you have to get elected, so first up is Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail. Whether running for or holding office, you'll find yourself in the media spotlight of Pageantry and Personalities, while espousing an ideology such as The Virtue of Selfishness can both attract and alienate voters.

Focusing on leaders and those who think they are is Presidents and Pretenders to the Throne, with one President so distinctive that we still say Nixon's the One. But holding onto power is treacherous—there's always the danger of an American Coup. And looking at upheavals in other countries, do you really think It Can't Happen Here?

Providing contrast to the American system is And Now for Something Completely Different. Kind of. Finally, Sublimely Ridiculous takes a cock-eyed view of presidents and politics, showing us that you can't always takes these things too seriously.

A note on the ratings: The film's rating reflects its cinematic qualities, in other words, how well it was made and how well it conveys its message regardless of what that message is.

Ratings are from one to five stars:

|

|

Classic. Transcendent filmmaking or storytelling that epitomizes a period, style, or genre. |

|

Excellent. Superior but not transcendent filmmaking or storytelling. |

|

|

|

Good. Filmmaking or storytelling of average value, or typical of a period, style, or genre. |

|

|

Fair. Fundamentally flawed technically and/or artistically, or an interesting failure. |

|

|

Poor. Technically inferior and/or artistically bankrupt; no redeeming qualities. |

Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although not discussed in alphabetical or chronological order below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() All the King's Men (1949)

All the King's Men (1949)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Best Man (1964)

The Best Man (1964)

![]()

![]()

![]() Bulworth (1998)

Bulworth (1998)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Candidate (1972)

The Candidate (1972)

![]()

![]() The Ides of March (2011)

The Ides of March (2011)

![]()

![]()

![]() The Last Hurrah (1958)

The Last Hurrah (1958)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Nashville (1975)

Nashville (1975)

![]()

![]()

![]() Primary Colors (1998)

Primary Colors (1998)

Credit for the title of this section of course goes to the late, great Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, whose exhaustive (exhausting?) opus Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72 chronicles the ups and downs of Democratic Senator George McGovern's ill-fated run in 1972 to unseat incumbent President Richard Nixon.

Laced with lurid flights of fancy such as Democratic candidate Edmund Muskie's unlikely ingestion of ibogaine during the New Hampshire primary to explain his odd behavior, Campaign Trail remains a political outsider's scathing indictment of not just party politics but of the mainstream media that covers them. What is most depressing is that the situation has become much worse since those days—then Thompson had to go and off himself in 2005 just when we need his crazed yet astute insights the most.

All politics is local, as former House Speaker Tip O'Neill liked to put it, so with these eight campaign-focused movies we begin at the municipal level and work our way up to the presidency.

![]()

![]()

![]() The Last Hurrah (1958)

The Last Hurrah (1958)

Directed by John Ford. Written by Frank S. Nugent, adapted from the eponymous novel by Edwin O'Connor.

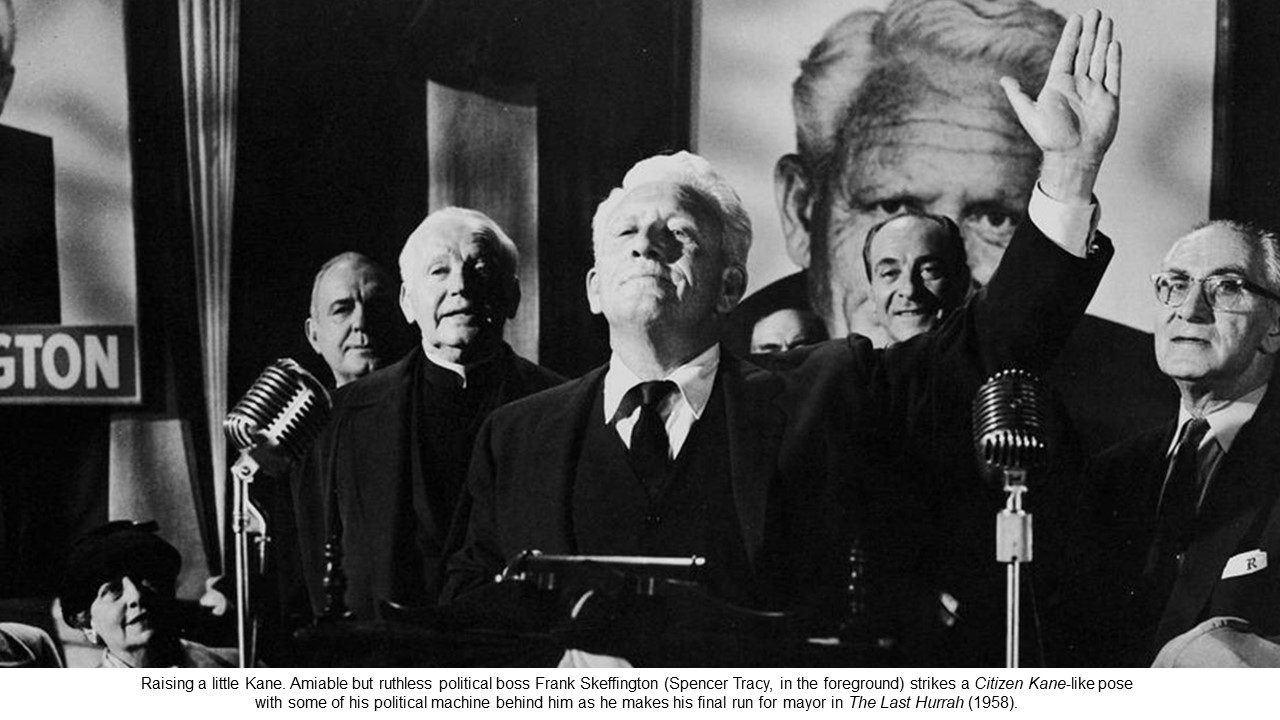

Starting with the local level, and most appropriately for O'Neill, who represented Boston, Massachusetts, in the US House of Representatives, Spencer Tracy gives his all for The Last Hurrah, his final campaign to remain mayor of "a New England city" not unlike Boston, in this political drama laced with sharp wit but burdened with lingering melodrama at the close. Tracy plays Frank Skeffington, the amiable but tough head of a well-oiled political machine that has earned him a loyal following—as well as equally dedicated enemies, led by banker Norman Cass (Basil Rathbone) and newspaper publisher Amos Force (John Carradine), backing political novice Kevin McCluskey (Charles Fitzsimons) to unseat Skeffington in his final election.

Given a ringside seat to his campaign by his Uncle Frank, Force's sportswriter Adam Caulfield (Jeffrey Hunter) watches savvy, cunning political boss Skeffington manage a widow's wake into a raucous political gathering and arm-twist Cass for the loan needed to fund a municipal housing development. The Last Hurrah nose-dives in its last act, which Ford stretches into gratuitous melodrama as the stock music swells mawkishly. Along with Ford mainstays Ken Curtis and Jane Darwell, Edward Brophy, Donald Crisp, and Pat O'Brien head the supporters giving Tracy The Last Hurrah.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() All the King's Men (1949)

All the King's Men (1949)

Written and directed by Robert Rossen, adapted from the eponymous novel by Robert Penn Warren.

Moving up to the gubernatorial level, Broderick Crawford came to prominence by playing Willie Stark, a naïve populist running for governor of an unnamed US state, although All the King's Men is loosely based on the life of Louisiana Governor Huey Long. The pivotal moment comes when Stark realizes that he has been set up as a dupe in the race: Shaking off his drunkenness while speaking at a county fair, Stark rouses the crowd with his candor and his promises to help the "hicks" of his state, among whom he counts himself, as Crawford delivers his signature performance as the politician with upstanding principles who inevitably succumbs to political corruption.

Cinematographer Burnett Guffey's angled shots, framed in dramatic black and white, lend All the King's Men its film noir atmosphere that cloaks its themes of idealism, pragmatism, and ultimately cynicism, with disillusionment and duplicity bubbling underneath as decadence and corruption permeate the narrative that sees Stark betray crusading reporter Jack Burden (John Ireland), who had championed Stark from his earliest days, and co-opt opposition operative Sadie Burke (Mercedes McCambridge) to be his fixer and would-be mistress. All the King's Men remains a (pardon the pun) stark lesson in Lord Acton's familiar dictum: "Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Candidate (1972)

The Candidate (1972)

Directed by Michael Ritchie. Written by Jeremy Larner.

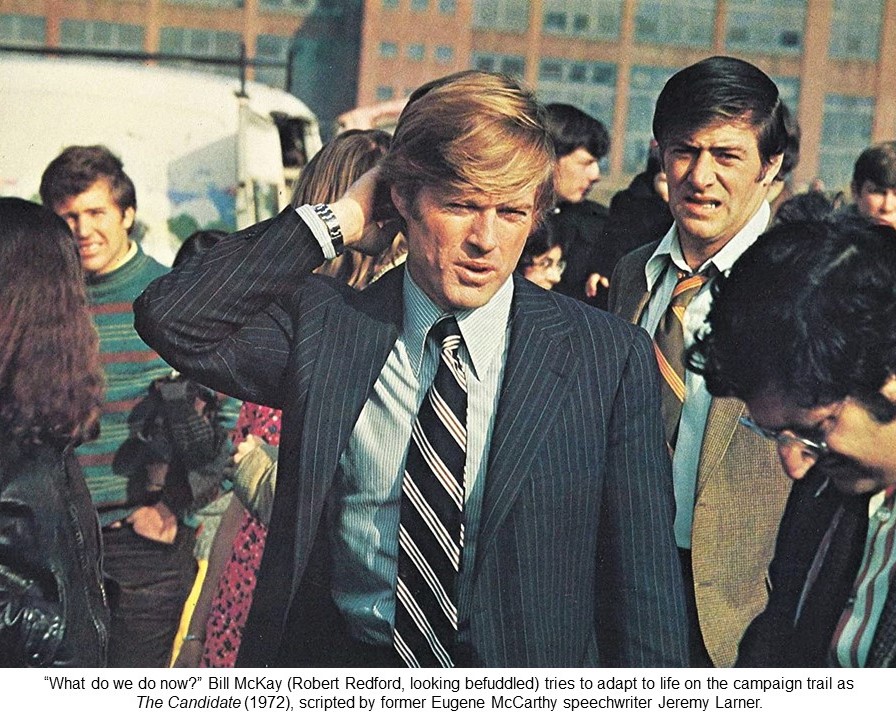

Robert Redford also finds his idealism tested on the campaign trail as Bill McKay, The Candidate whose pivotal moment comes during his debate with incumbent Republican Crocker Jarmon (Don Porter) for Jarmon's seat as a US Senator from California. McKay goes off-script to decry all the issues the two candidates are not discussing, rattling Jarmon and irritating his own handlers (played by Peter Boyle and Allen Garfield), although McKay's rant ultimately signals his last moment of idealism and his turn toward slick pragmatism, a dynamic that distinguishes the unsentimental yet not quite cynical script by Larner, who had been Senator Eugene McCarthy's speechwriter during McCarthy's 1968 presidential bid.

Released at the height of the 1972 presidential race, the subtly satiric The Candidate echoes the quixotic George McGovern campaign while applying the hard lessons of recent politics that spurred Redford and Ritchie to make the film. With Jarmon considered a shoo-in for re-election, community activist McKay is enticed into running by the opportunity to use the race as a platform for unorthodox political positions, but despite early indifference and even hostility, McKay gradually begins to build a groundswell of support that is so successful—and so unexpected—that it prompts The Candidate's closing punchline familiar to countless underdogs: "What do we do now?" Ritchie's verité direction and committed performances, especially by Redford, keep The Candidate on the ballot.

![]()

![]()

![]() Bulworth (1998)

Bulworth (1998)

Directed by Warren Beatty. Written by Beatty and Jeremy Pikser.

But instead of staying on the ballot, Beatty dives into outrageous political satire in Bulworth as Democratic US Senator Jay Bulworth (Beatty), needing to revitalize his campaign, formulates a different re-election strategy: He purchases a $10 million life insurance policy, a sop to the insurance industry, names his daughter as sole beneficiary, and, grown weary of Beltway power bargaining and his façade of marriage to wife Constance (Christine Baranski), arranges to have himself assassinated. Then, back in Los Angeles for last-minute campaigning, he speaks truth to power. Boy, does he ever.

Tapping piquantly into black urban culture, Bulworth broadcasts acute, often cutting observations clearly from the left-liberal spectrum about the state of the union that would sound preachy in a conventional drama but have mixed results as a comedy, with Bulworth dissing blacks in South Central, kvetching about Hollywood Jews in Beverly Hills, and hooking up with Nina (Halle Berry), who knows more than she lets on, all as Bulworth, who hasn't slept in days, begins rapping—yes, rapping—about how it's all going down. Does Bulworth work? Partly. Beatty leans too heavily on African-American tropes while populating the white establishment with cardboard cutouts, with the assassination simple catalyst and his reappraisal hinging on contrivance. On the plus side, the pungent humor hits enough marks as the whirling narrative stays lively. Bulworth plays the clown—because only the jester can risk telling the awful truth.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Best Man (1964)

The Best Man (1964)

Directed by Franklin Schaffner. Written by Gore Vidal, adapted from his eponymous play.

That awful truth raises the stakes higher as you move up the ticket, and who better to parse the intricacies of presidential politics than Vidal, whose acclaimed 1984 historical novel Lincoln garnered praise from across the political spectrum, and who adapted his own play for Schaffner's film version of The Best Man, an unyielding examination of candidates jockeying for their party's presidential nomination at a contentious convention in Los Angeles, with former President Art Hockstader (Lee Tracy) a potential kingmaker.

Henry Fonda is William Russell, glib but thoughtful, a liberal former secretary of state, and Cliff Robertson is Joe Cantwell, a hard-nosed, hardline conservative with more than a touch of Richard Nixon about him. Russell's infidelities (a nod to John F. Kennedy) and mental health issues give Cantwell a trump card over him—and Cantwell is not afraid to use it.

But when Cantwell's old army comrade (Shelley Berman) offers dirt to Russell, he must decide whether to abandon the high road even to stop Cantwell in this taut, sharp, prescient forum for Vidal's cutting home truths about politics reduced to "gossip instead of issues, personalities instead of policies," all captured in cinematographer Haskell Wexler's unvarnished black-and-white framing—and don't think we've seen the last of Wexler or of "gossip instead of issues, personalities instead of policies," either.

![]()

![]()

![]() Primary Colors (1998)

Primary Colors (1998)

Directed by Mike Nichols. Written by Elaine May, adapted from Joe Klein's eponymous novel.

A thinly-veiled account of Bill Clinton's successful 1992 run for the presidency, Primary Colors offers up "Jack Stanton," played by John Travolta, who exudes enough Dixie charisma to pass as a Clinton surrogate and who, with wife Susan (Emma Thompson) more or less by his side, lights out on the campaign trail as the wonkish governor from a nowhere Southern state (never named, but y'all can guess) determined to become the Democratic nominee for president.

May's lively, sometimes rollicking script bristles with knowing barbs as young up-and-comer Henry Burton (Adrian Lester) is inveigled into the campaign, teaming with spokeswoman Daisy Green (Maura Tierney) and James Carville stand-in Richard Jemmons (Billy Bob Thornton) as obstacles appear in Stanton's path: evasions over youthful activities, followed by allegations of sexual indiscretion, first with Susan's hairdresser, then with their teenaged babysitter, with the Stantons' old friend, brutal fixer Libby Holden (Kathy Bates), tasked to douse the fires—until her discovery of how ruthless the Stantons really are rattles her. Primary Colors bursts forth like a front-runner—Travolta eerily captures Clinton's "I feel your pain" solicitude—but Nichols's patented surface sheen atop Klein's facile source material all but guarantees a fade before we get to the convention.

![]()

![]() The Ides of March (2011)

The Ides of March (2011)

Directed by George Clooney. Written by Beau Willimon, adapted from his play Farragut North, with Clooney and Grant Heslov.

Speaking of facile material and surface sheen, the too-familiar The Ides of March emerges as a West Wing episode writ large with contrived melodrama that aims for electoral sophistication but hits a series of shallow clichés, both personal and political, from start to finish. Clooney stars as Mike Morris, the governor of one battleground state, Pennsylvania, running for the Democratic presidential nomination in another battleground state, Ohio, where his challenger, Arkansas Senator Ted Pullman (Michael Mantell), could win the state with the help of influential Senator Thompson (Jeffrey Wright).

Each candidate has his campaign soldiers trying to engineer the deals. For Pullman, it's crafty Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti), and for Morris, it's grizzled veteran Paul Zara (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and young Turk Stephen Meyers (a vapid Ryan Gosling), whom Duffy tries to lure into the Pullman camp. Meyers himself is successful in luring young Morris intern Molly Stearns (Rachel Evan Wood) into his bed, and while accidentally answering Molly's mobile phone late one night, he discovers that she and Morris shared a brief tryst. Already we're faced with tired, predictable devices, both literally (the cell phone) and figuratively (the sexual affairs), and compounding the labored storytelling is the jockeying by the three campaign managers, particularly the temptation Duffy offers Meyers. Savvy politico Clooney tries to deliver a meaty moral but serves up an unconvincing trifle instead. Beware The Ides of March.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Nashville (1975)

Nashville (1975)

Directed by Robert Altman. Written by Joan Tewkesbury.

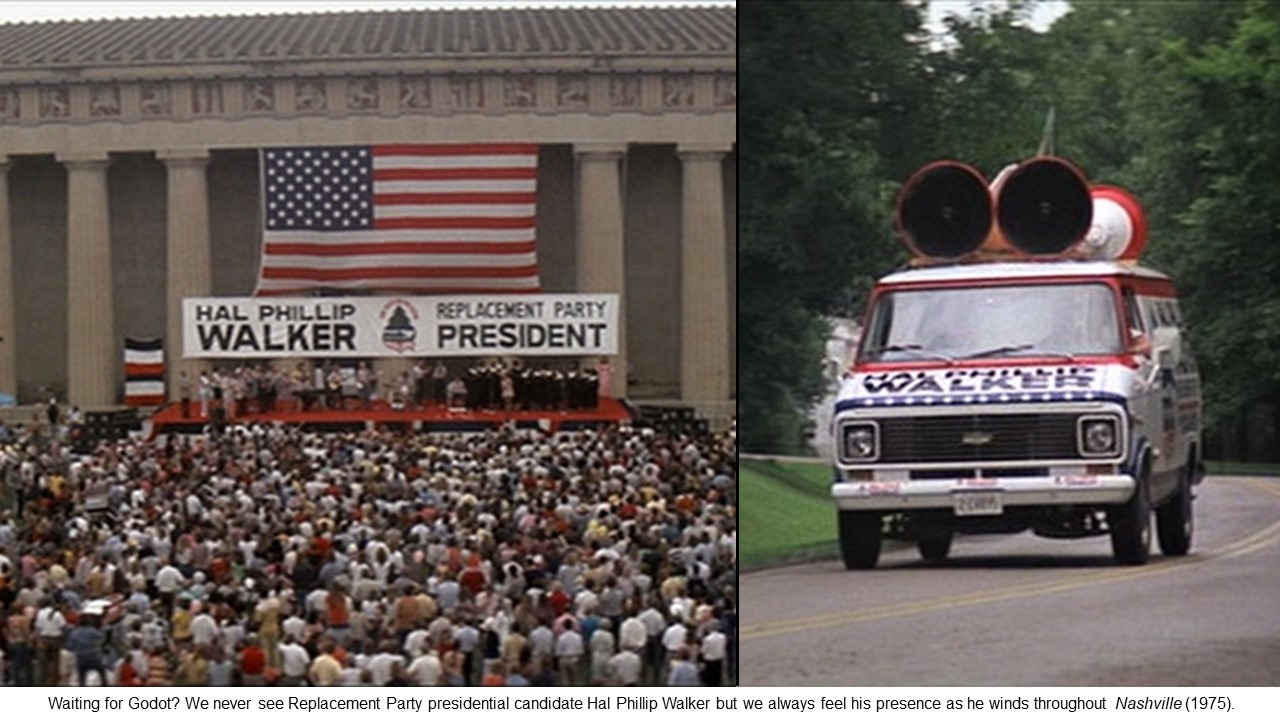

Our final campaign stop is in Nashville, which, at least overtly, is focused on country music, the chief industry of "Music City, U.S.A." But Altman's sprawling yet masterful opus opens with the drone of one Hal Phillip Walker (Thomas Hal Phillips), his flat voice blaring from the loudspeaker atop his van that identifies him as the presidential candidate for the "Replacement Party," slowly winding his way through the city streets, and it ends at a benefit concert for Walker at the (Nashville) Parthenon, where an assassination attempt occurs.

Seen in that respect, Nashville sits at an American crossroads musically, spiritually, politically, geographically, and chronologically, in many ways the most astute and compelling cinematic summation of a decade-plus of the social and cultural upheaval that changed the United States in the 1960s and early 1970s—changes that remain contentious even today. We never see Walker, but we do see John Triplette (Altman stalwart Michael Murphy), Walker's unctuous advance man, schmoozing the local luminaries including Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson), part of country music's aristocracy with political ambitions of his own, first seen recording his stirring if schmaltzy ode to the upcoming Bicentennial, juxtaposed with Linnea Reese's (Lily Tomlin) session singing for gospel performer Tommy Brown (Timothy Brown)—already displaying contrasts in race and musical forms.

Walker's voice, and its plainspoken populist message, winds sonorously through Nashville and its array of dramas, musical and non-musical, played out on large and small stages by, among others, Ned Beatty, Karen Black, Ronee Blakely, Keith Carradine, Geraldine Chaplin, Shelley Duvall, and Barbara Harris—and have fun identifying the actual country-music personages in some of their characters. (Hint: Think "Coal Miner's Daughter" when you see Blakely.)

Pageantry and Personalities

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although discussed (generally) chronologically below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Bombshell (2019)

Bombshell (2019)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Citizen Kane (1941)

Citizen Kane (1941)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() A Face in the Crowd (1957)

A Face in the Crowd (1957)

![]()

![]()

![]() The Front Runner (2018)

The Front Runner (2018)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Good Night, and Good Luck. (2005)

Good Night, and Good Luck. (2005)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Medium Cool (1969)

Medium Cool (1969)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Network (1976)

Network (1976)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() State of Play (2003)

State of Play (2003)

![]()

![]()

![]() State of Play (2009)

State of Play (2009)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Truth (2015)

Truth (2015)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Wag the Dog (1997)

Wag the Dog (1997)

Mainstream media, or as Sarah Palin so wittily dubbed it, "lamestream" media, takes a drubbing from all points on the political spectrum for its perceived biases. By and large, the MSM (as the shorthand goes) deserves it. We could launch into discourses on ideology—conservatives think the MSM is too liberal while liberals think it's too conservative—or on economics, of how, as Ben Bagdikian noted way back in his landmark 1983 study The Media Monopoly, media outlets, primarily television, not only commodified the news but began to consolidate ownership of its outlets into fewer and fewer hands.

But to boil it down to basics, the MSM has devolved into what I call Pageantry and Personalities. A pageant is, to be polite, a stylized representation that delivers a shallow understanding while emphasizing surface attractions—think of a beauty pageant, ostensibly an appreciation of womanhood but one that extols only women's superficial qualities. To be blunt, a pageant is a pretense, an ostentatious display, which is what the mainstream media has become. Issues do not get in-depth explorations that could foster understanding; they get personalities that either support or oppose an issue, with the ensuing talkfest—cue the array of insets on your television screen, each containing a talking head just waiting to pontificate, usually over someone else—the "debate" that doesn't enlighten or even inform very well; it only raises the blood pressure.

How did we get here? The movies in this section might not provide a direct answer, but they do illustrate that media has been intertwined with politics to such an extent that perception is politics, and that perception reflects the framing by the media, which any media-savvy president, from FDR and JFK to Reagan and Trump, knows how to manipulate.

Fittingly, then, as media sources have multiplied in the last few decades, so too have the number of movies that stress the marriage of media and politics; thus, the bulk of these movies are from the more recent decades. However, four pre-Reagan movies illustrate the groundwork upon which the newer movies have built.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Citizen Kane (1941)

Citizen Kane (1941)

Directed by Orson Welles. Written by Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz.

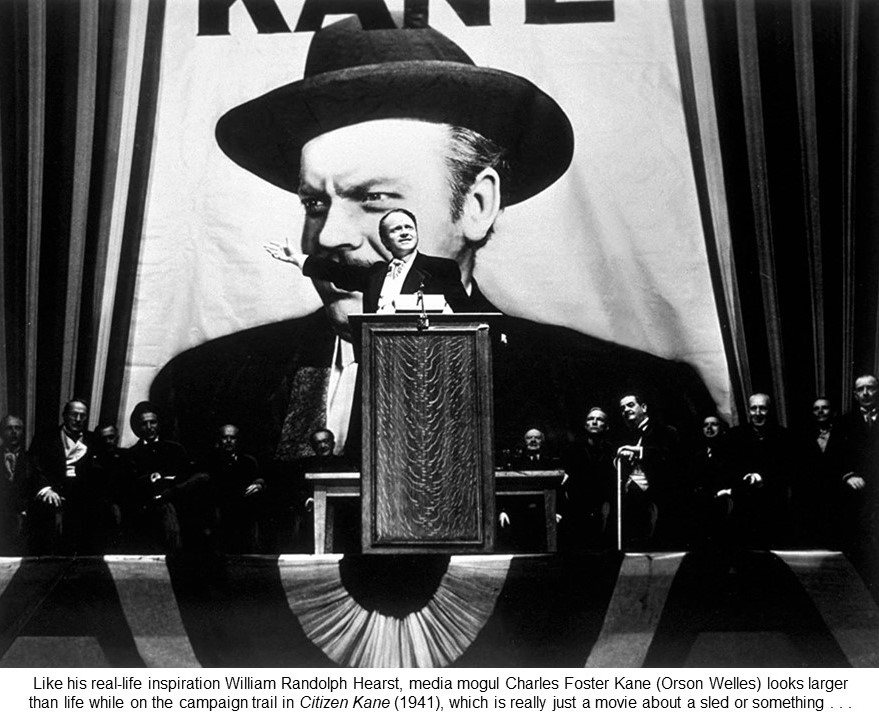

To be sure, pageantry and personalities has been around for a long time, epitomized by "yellow journalism," sensationalistic, dubiously-sourced reporting that we now call tabloid journalism, with a giant practitioner being William Randolph Hearst, the media mogul of his era whose influence and personality are echoed by the likes of Fox News maven Rupert Murdoch. Citizen Kane is the fictional, thinly disguised profile of Hearst that also made Welles a legend as he and Mankiewicz tell the tale of Charles Foster Kane, the Hearst alter ego who transcended his humble origins to cast his mighty shadow over American politics and society.

Leaving Colorado to launch his own newspaper in New York, initially with high ideals (the iconic "Declaration of Principles" scene), Kane soon resorts to yellow journalism even as his paper's influence is weighty enough to push the United States into the Spanish-American War (Kane paraphrases Hearst's actual directive to a reporter stationed in Cuba as, "You provide the prose-poems, I'll provide the war"). Aspiring to public office himself, Kane, against a backdrop of himself in a gigantic poster, challenges incumbent New York governor Jim Gettys (Ray Collins) with a fiery speech in Madison Square Garden as cinematographer Gregg Toland's sumptuous black-and-white photography captures the literally larger-than-life Kane in full self-righteous glory.

What a comeuppance, then, when Gettys discovers Kane's love nest housing aspiring singer Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore), a scandal that ends both Kane's political ambitions and his marriage to Emily (Ruth Warrick), who just happens to be the niece of a former president. We'll forego the eternal debate about whether Citizen Kane is the greatest movie ever to note simply that it still casts a mighty shadow over our impressions of the news media.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() A Face in the Crowd (1957)

A Face in the Crowd (1957)

Directed by Elia Kazan. Written by Budd Schulberg.

While Citizen Kane illustrates, among other points, how the media can manipulate public opinion, A Face in the Crowd demonstrates how someone can use the media to manipulate the public—and if you know Andy Griffith only as a genial small-town sheriff or a folksy defense attorney from nostalgia TV, wait until you get a load of him here. Griffith stars as "Lonesome" Rhodes, discovered by local radio reporter Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal) in a rural Arkansas drunk tank who is taken by his folksy, bumpkin manner and particular appeal to women—to which she is hardly immune. A hit with his own show, Rhodes displays his ambition and powers of persuasion as he moves to Memphis, then to New York, where he becomes a national icon with his own television show.

Screenwriter Schulberg proved remarkably prescient about the power of television, still in its early stages, to magnify the cult of personality to demagogic levels while suggesting his own cynicism (not entirely unfounded) about the gullibility of audiences even then as director Kazan proves equally capable of framing the message evocatively, if hardly subtly. Behind the scenes, Lonesome's down-home charm evaporates as the shrewd, egotistical, manipulative, often spiteful Rhodes reveals his contempt toward an adoring public that made him a sensation. What's more, his sponsor (Percy Waram) is grooming a stodgy, reactionary senator (Marshall Neilan) for president—and he sees Rhodes as the ideal tutor to give him a makeover to make him more appealing to the unwashed masses. The ending of A Face in the Crowd flags with the predictable comeuppance, but its overall message remains bracing—and uncomfortably contemporary.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Medium Cool (1969)

Medium Cool (1969)

Written and directed by Haskell Wexler.

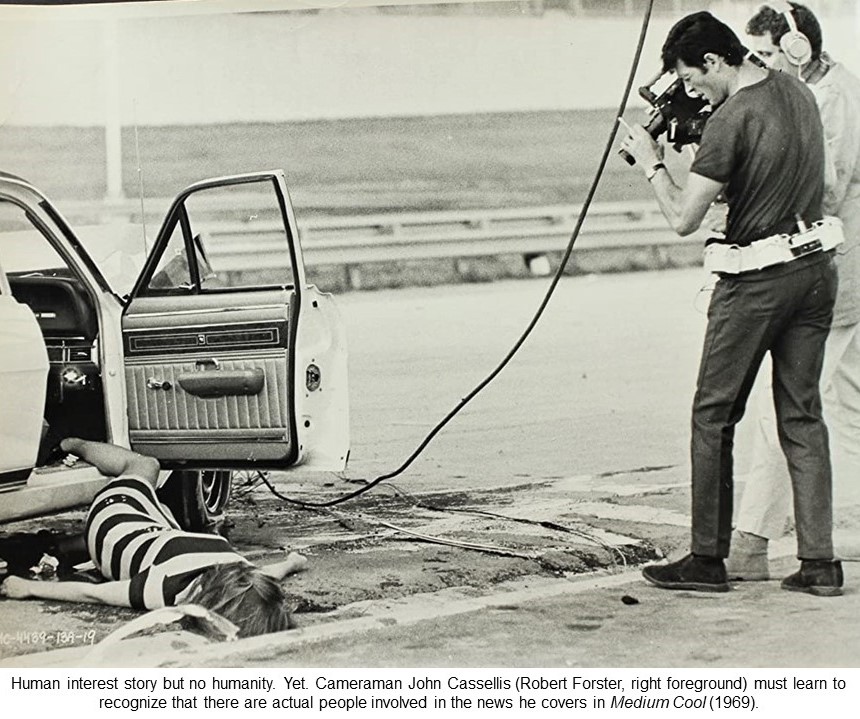

Television factors into Medium Cool by focusing on John Cassellis (Robert Forster), a news cameraman with an instinct for the story if not for the people making the story: In a telling early scene, he and his sound man Gus (Peter Bonerz) become more concerned about shooting effective footage of a road accident that had just happened than with helping the victims. Then again, Wexler, best known as a premier cinematographer who filmed Medium Cool himself, pulls no punches in his unsentimental portrait of Chicago at the height of the bloody, infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention that further polarized an already-divided nation and led to the election of Republican Richard Nixon as president.

Wexler adapted the title Medium Cool from Marshall McLuhan's description of television as a "cool" medium whose detachment and lack of context requires you to fill in the blanks yourself. Wexler compels his viewers to do the same with his skeletal story, which forces them to probe Cassellis's motivations even as the detached professional finds himself pulled more closely into the political upheaval while discovering that his stories have been handed over to the FBI by his own station's management. Wexler's ending is a contrived cliché, but his final shot, when he swings his camera around to face the camera filming him—in other words, forcing his audience to acknowledge that it is part of the story—is unforgettable.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Network (1976)

Network (1976)

Directed by Sidney Lumet. Written by Paddy Chayefsky.

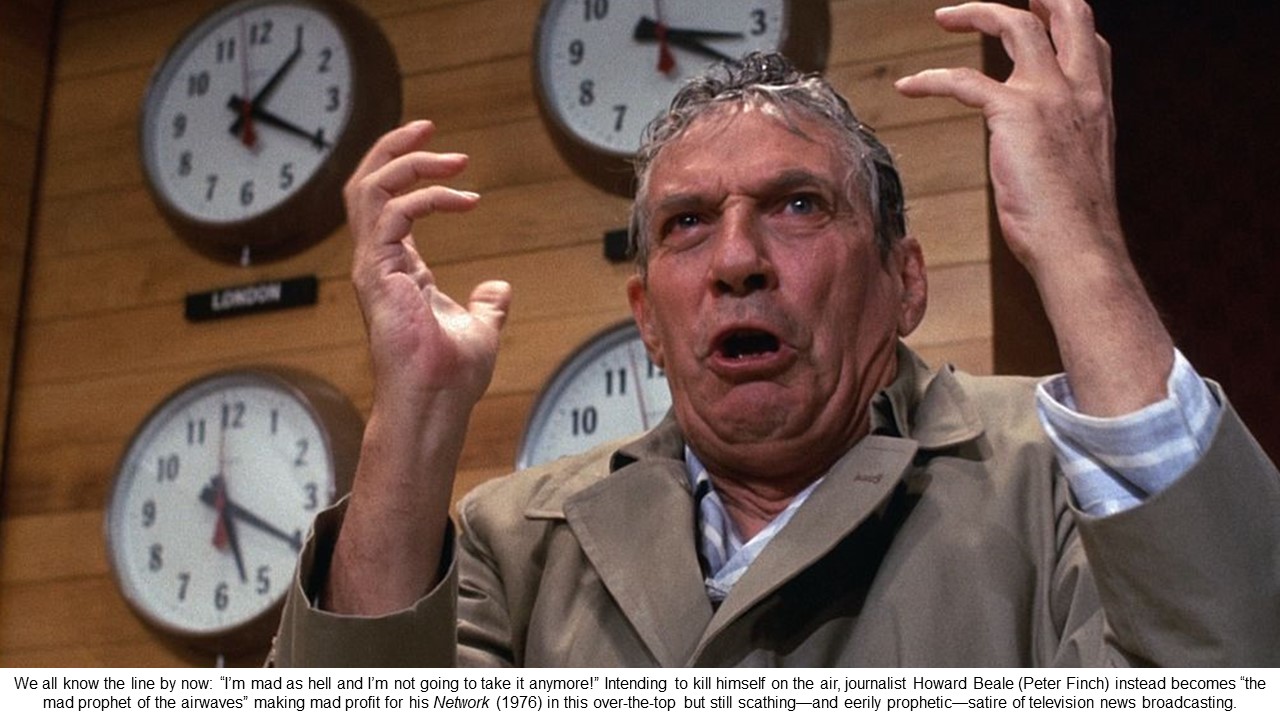

Taking television to new heights—or depths—Network is truly the transitional movie here, consolidating previous fears and anxieties about the increasingly pervasive medium while offering an outrageous—and chilling—preview of where television was going. Guess what? Their future is our current reality television—and our current reality-television president.

About to be fired for low ratings, television news anchor Howard Beale (Peter Finch) announces that he will kill himself on-air before his old chum and fellow unemployment recipient Max Schumacher (William Holden) convinces him to make a dignified exit. Instead, Howard rants on-air that he's mad as hell and he won't take it anymore. Lo! His audience feels the same way. Presto! He's back on top as the "mad prophet of the airwaves"! Make that mad profit for his network, the fictitious UBS, as entertainment-programming genius Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway) steers Howard to national fame—an eerie foreshadowing of what really did happen to television news just a few years after Network was first released.

Lumet (Twelve Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon) knew how to transmit a social message while never losing sight of the individual lives that compose that society. Pairing him with legendary "Golden Age of Television" writer Chayefsky should have been a dream teaming. Overall, it is, as Network looks as relevant (if not more so) today as it did nearly a half-century ago. But Chayefsky's script produces characters who emit stilted, affected speech on the way to an utterly cynical, rapacious, business-driven ending. Still, Ned Beatty's glorious scenery-chewing as he berates Howard for the folly of believing that countries, not transnational corporations, make the rules of the world remains an object lesson in realpolitik, one that Donald Trump certainly understands, if only on a transactional level.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Wag the Dog (1997)

Wag the Dog (1997)

Directed by Barry Levinson. Written by David Mamet and Hilary Henkin, based on Larry Beinhart's novel American Hero.

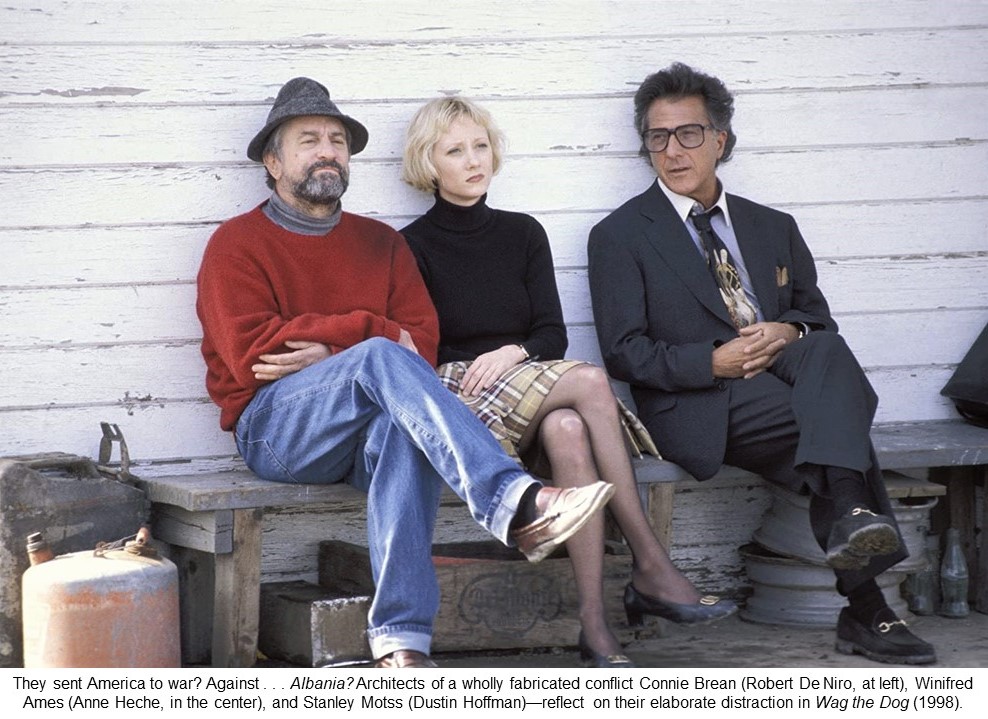

Outrageous television (among other mediums) combined with equally scandalous political theater distinguishes Wag the Dog, which manages not only to recap then-contemporary political foibles but eerily presage upcoming ones. The contemporary foibles include a US president caught making advances on a "Firefly Girl" just days before his hoped-for re-election—shades of Bill Clinton's l’Affaire Lewinsky, oui?—which sends West Winger Winifred Ames (Anne Heche) springing into damage control. Her first call is to shadowy spin doctor "Connie" Brean (Robert De Niro), whose solution is to concoct a fictitious war with . . . Albania, subcontracting the production of the war to a real Hollywood producer, Stanley Motss (Dustin Hoffman), to make the deception look realistic. And is it ever—until one detail develops a life of his own.

Director Levinson dwells on these juicy details, whether it's Motss's staging an "Albanian" girl's (Kirsten Dunst) "escape" from a "war-torn" village—actually a green screen on a sound stage—or enlisting Willie Nelson and Pops Staples to write a "vintage" folk song, "Old Shoe, " about a missing US soldier, with a secretly psychotic Woody Harrelson playing that soldier whose circumstances are an eerie preview of the Jessica Lynch deception during the early stages of the 2003 Iraq War. And just wait until you see CIA operative William H. Macy "end" the "war." What is truly frightening about Wag the Dog is not just how seamlessly it fabricates reality but how easily it is accepted as truth—Orwellian doublespeak and revisionism in the 24-hour news cycle. And in an age with a reality-television star as president, Wag the Dog remains, tragi-comically, all too relevant.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() State of Play (2003)

State of Play (2003)

Directed by David Yates. Written Paul Abbott.

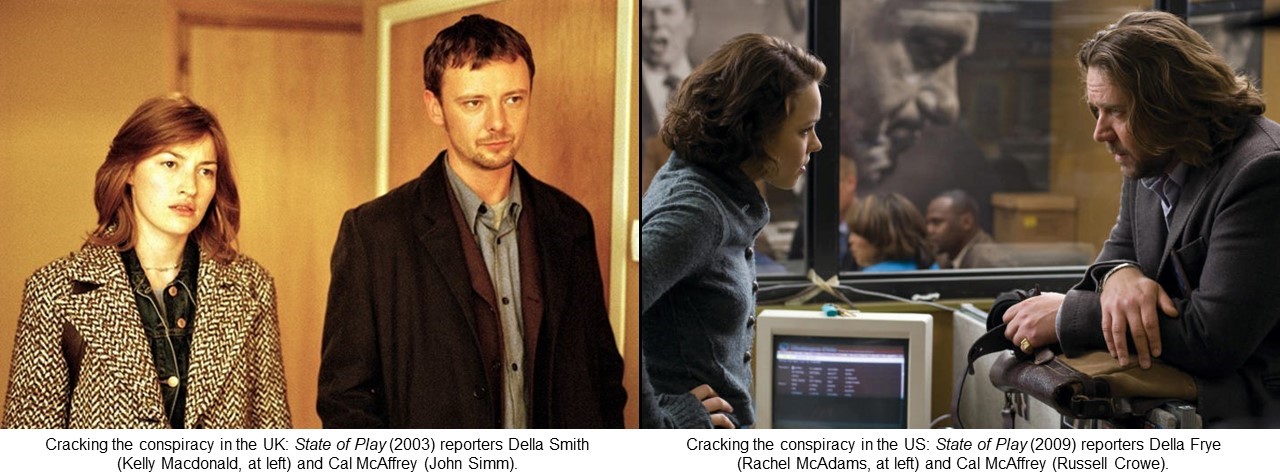

Mixing political chicanery, media scrutiny, and interpersonal relationships, the ambitious State of Play marshals a wealth of narrative and characterization into a generally compelling story that commands attention and rewards close examination. This six-part BBC miniseries is the only television production included in this voters' guide because it was adapted directly into a 2009 feature film (discussed below). The British take on State of Play uses the apparent suicide of a young female researcher beneath a London subway train as the impetus into a complex web of connections that lead to Minister of Parliament Stephen Collins (David Morrisey), for whom the woman had been working. Reporter Cal McCaffrey (John Simm), who once worked for Collins, offers his sympathy as he is investigating the apparently drug-motivated killing of a young black man—but when a briefcase in the man's possession contains surveillance material on the dead researcher, McCaffrey enlists fellow reporter Della Smith (Kelly Macdonald) to help investigate a thickening plot.

Oh, boy, does the plot thicken. Spurred by their editor Cameron Foster (the always-enjoyable Bill Nighy), McCaffrey and Smith begin to uncover a larger, Byzantine thread that points to governmental and industrial corruption and conspiracy through increasing degrees of realization and on the kind of grand scale that British drama seems able to shrug off as easy as breathing without becoming grandiose, melodramatic, or, crucially, unbelievable—a testament to Abbott's ability to concoct a rich, complex story. With six hours of narrative, State of Play cannot help but be sprawling and occasionally padded, but Yates's steady direction keeps the lanes straight as the principals, supported by James McAvoy, Polly Walker, and Marc Warren, whose near-manic PR flack Dominic Foy is almost comic relief, make the connections clear and compelling.

![]()

![]()

![]() State of Play (2009)

State of Play (2009)

Directed by Kevin Macdonald. Written by Matthew Michael Carnahan, Tony Gilroy, and Billy Ray, based on Paul Abbott's eponymous teleplay.

The American movie adaptation of State of Play, directed by Macdonald seemingly after repeated screenings of All the President's Men, distills the miniseries' general premise but, now set in the United States, many of the specific references become more identifiable in an American context. The young researcher tied to now-Senator Stephen Collins (Ben Affleck) emerges as an analog to the 2001 disappearance and murder of Chandra Levy, a federal intern who had been having an affair with Democratic Representative Gary Condit, while PointCorp, a shadowy private security contractor fallen under Collins's scrutiny, echoes the description of Blackwater, the de facto American mercenary army infamous for its massacres in Iraq.

Cal McAffrey (Russell Crowe) is now a grizzled Washington Globe beat reporter investigating a local shooting who locks horns with the paper's young online blogger Della Frye (Rachel McAdams) investigating the researcher's death until, with the blessing of Globe editor Cameron Lynne (Helen Mirren), they join forces to prove that the aide was murdered to discredit Collins's investigation into PointCorp. Of course, there is a plot twist lurking, facilitated by sleazy public relations flak Dominic Foy (a delightfully greaseball Jason Bateman) working for PointCorp, leading to an unsurprising conclusion. Jeff Daniels and Robin Wright add interest to this earnest if unexceptional political drama, although any Washington thriller that can squeeze Gil Scott-Heron's cutting Reagan critique "B Movie" onto the soundtrack can't be all bad.

![]()

![]()

![]()

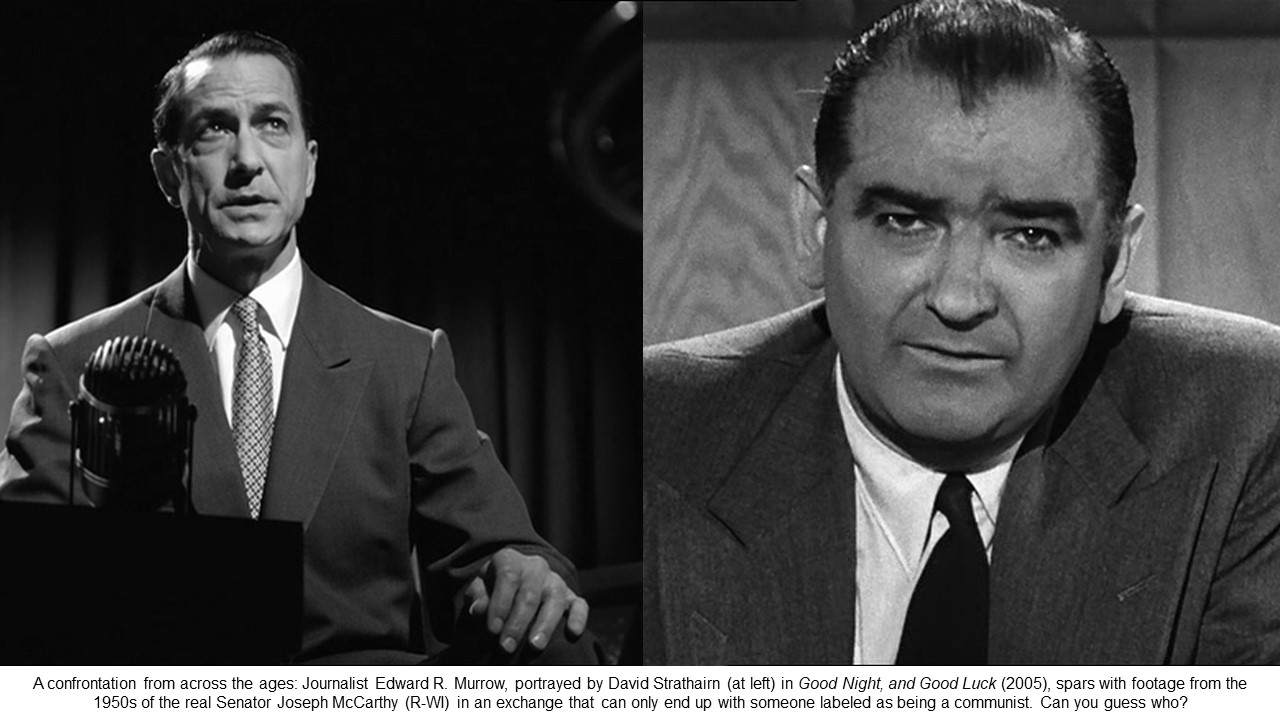

![]() Good Night, and Good Luck (2005)

Good Night, and Good Luck (2005)

Directed by George Clooney. Written by Clooney and Grant Heslov.

Delving back into the 1950s, Good Night, and Good Luck features David Strathairn portraying legendary journalist Edward R. Murrow and battling archival footage of Senator Joseph McCarthy during that decade's Red Scare, with Robert Elswit's seamless black-and-white photography defusing that potential conceit. Murrow, a crusading pioneer in television's early days, incurs McCarthy's wrath when he dares to criticize McCarthy's bullying tactics, which have cowed the nation, gripped in Cold War paranoia, that include McCarthy's threats of labeling someone a communist, a charge that taints fellow journalist Don Hollenbeck (Ray Wise). And although CBS head William Paley (Frank Langella) supports Murrow, it comes at the cost of alienating advertisers like aluminum giant Alcoa.

Clooney and Heslov's taut, effective script captures the clipped newsmen's dialogue and mid-century attitudes without ostentation while Clooney's direction, his shots perhaps a shade self-consciously arty, nevertheless evokes the tenseness of the time and Murrow's sense of purpose without melodrama, particularly when Murrow realizes that he's won the battle but lost the war. Reserved, unemotional, but resolute, Strathairn holds the center of the film, which, bookended by scenes of Murrow's prescient 1958 speech warning not to fritter away television's power on cheap entertainment, drives home a timeless message that surely resonates today and makes Good Night, and Good Luck, Murrow's sign-off phrase, enlightening and compelling.

![]()

![]()

![]() The Front Runner (2018)

The Front Runner (2018)

Directed by Jason Reitman. Written by Reitman with Jay Carson and Matt Bai, based on Bai's book All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid.

News media proved to be the downfall of Gary Hart, a Democratic rising star from Colorado who attracted favorable comparisons to John F. Kennedy when he ran for president in 1988 and quickly became The Front Runner. Like Kennedy, Hart (Hugh Jackman) was also known as a womanizer—but unlike JFK, it proved to be his undoing when the Miami Herald, staking out Hart on an anonymous tip, reported that a woman, Donna Rice (Sara Paxton), spent the night at Hart's Washington, D.C., townhouse while his wife Lee (Vera Farmiga) was still in Colorado. The ensuing media frenzy soon forced Hart to withdraw from the race (although he re-entered briefly during the early primaries).

Director Reitman starts The Front Runner off with a bang. Hart, with Lee on the periphery, hits the campaign trail flanked by staffers led by Bill Dixon (J.K. Simmons) firing off glib, profane dialogue, like West Wingers given permission to swear, in a narrative punctuated by Rob Simonsen's spare, percussive score as editor Stefan Grube sweats the fast cuts while blending in archival footage. Then Hart goes to Miami, meets Rice—and sets the media off to the races. After its manic first half, The Front Runner throttles back for a ruminative look at how the scandal mushroomed to swallow Hart's momentum, not helped by his clipped, cursory responses at a contentious press conference, but it also swallows the momentum of this shallow, extended vignette that produces tepid heat but no enlightenment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Truth (2015)

Truth (2015)

Written and directed by James Vanderbilt, based on the book Truth and Duty: The Press, the President and the Privilege of Power by Mary Mapes.

During the 2004 election, CBS's 60 Minutes aired an exposé delivered by journalist Dan Rather (Robert Redford) alleging that George W. Bush, seeking his second term as president, had received preferential treatment and had made unauthorized absences while serving in the Texas Air National Guard during the Vietnam conflict, with the smoking gun being copies of memos written by Bush's commander that were furnished to CBS by former Air National Guard officer Bill Burkett (Stacy Keach). However, the political blogosphere quickly challenged the veracity of the documents, prompting media scrutiny and subsequent backpedaling by CBS, which launched an internal investigation that targeted producer Mary Mapes (Cate Blanchett), whose team was unable to fully vet the memos because of scheduling pressures.

The hard-hitting docudrama Truth examines this controversy with little subtlety as Vanderbilt plunges ahead with slick convention and hastily drawn characterizations, underlined heavily by Brian Tyler's plangent score, and its unabashed championing of Mapes and her team (which includes Topher Grace, Elisabeth Moss, and Dennis Quaid) is guaranteed to polarize viewers with established political convictions. Yet conviction drives the essence of Blanchett's dynamic performance—she is the very heart of Truth—which lifts Vanderbilt's directorial debut above merely satisfactory as Redford, no stranger to cinematic and political conflict, delivers a nice emeritus turn. So, is Truth a lie? Better examine the evidence before you draw your conclusion.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Bombshell (2019)

Bombshell (2019)

Directed by Jay Roach. Written by Charles Randolph.

As the head of Fox News, Roger Ailes (John Lithgow) changed the face of cable-television news by developing a confrontational, unabashedly partisan format and by emphasizing the sex appeal of female anchors and reporters, paternalistic sexism that prompted his 2016 ouster from Fox amidst a slew of sexual-harassment allegations beginning with Gretchen Carlson's (Nicole Kidman) following her departure from Fox. Bombshell takes an up-close and personal look at the events leading up to the bombshell revelations against Ailes as Randolph's combustible script sweeps knowingly across the newsroom and director Roach sets a deliberate pace.

But Bombshell has a double meaning: Telling the tale isn't just Carlson but also Megyn Kelly (Charlize Theron), replacing Carlson in Fox's primetime while drawing blood in a public feud with then-Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump, and Kayla Pospisil (Margot Robbie), a (fictitious) young up-and-comer eager to land an on-air role—even if that requires a humiliating private audition before Ailes. Taken together, the three women—all attractive blondes—form the life cycle of the bombshell Fox newswoman, with Theron's Kelly the crucial linchpin in tipping credibility for the harassment claims in favor of the victims. Lithgow delivers a choleric, sometimes creepy performance that touches lightly on caricature in this diffuse yet forceful lead story that indeed drops a Bombshell.

Comments powered by CComment