Index

Presidents and Pretenders to the Throne

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although not discussed in alphabetical or chronological order below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The American President (1995)

The American President (1995)

![]()

![]()

![]() J. Edgar (2011)

J. Edgar (2011)

![]()

![]() Kisses for My President (1964)

Kisses for My President (1964)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Lincoln (2012)

Lincoln (2012)

![]()

![]() The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977)

The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Sunrise at Campobello (1960)

Sunrise at Campobello (1960)

![]()

![]()

![]() Vice (2018)

Vice (2018)

![]()

![]() W. (2008)

W. (2008)

With two exceptions, these movies deal with actual personages although there must be many Democrats who still wish that the fictitious President Andrew Shepherd, played by Michael Douglas, in The American President was really, really who Bill Clinton was supposed to be. Otherwise, these movies based on real political figures, most of them US presidents, present them in various shades of equally varying effectiveness ranging from adulatory to sympathetic to less than either.

We'll begin with the movies depicting the two fictional presidents before moving onto the movies that portray actual presidents—as well as two remarkable characters in American politics who might as well have been president given their power and ambition.

![]()

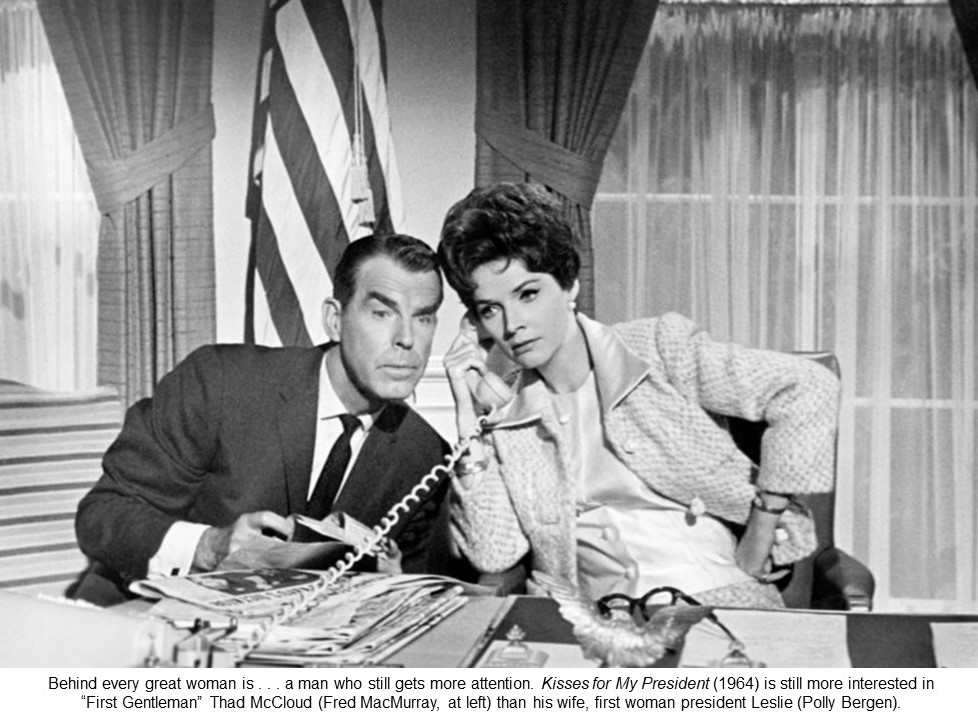

![]() Kisses for My President (1964)

Kisses for My President (1964)

Directed by Curtis Bernhardt. Written by Claude Binvon and Robert Kane, adapted from a story by Kane.

Kudos to Kisses for My President for an unprecedented premise: The United States elects its first woman president, Leslie McCloud (Polly Bergen). Unfortunately, this light-hearted but ultimately patronizing comedy treats that premise as a joke while focusing on how hubby Thad (Fred MacMurray) reacts to being the "First Gentleman" left to twiddle his thumbs while his wife is preoccupied with—you know, being president and all—until a situation unique to women forces a reappraisal of the chief executive's priorities. Barely ensconced in office, Leslie faces political pressure from opposition Senator Walsh (Edward Andrews), who pushes for renewed aid for visiting Latin American dictator Raphael Valdez, Jr. (Eli Wallach).

Dispatched to entertain Valdez, Thad embarrasses the president in a well-publicized altercation at a strip club. Then Thad's old flame Doris Reid (Arlene Dahl) offers him a job to boost her company's brand. Finally, their kids (Ahna Capri, Ronnie Dapo) begin to run wild. What's a mother to do? Bernhardt steers this narrative between slapstick and smarts: Valdez, despite Wallach's parodic stereotype, symbolizes the dark side to American foreign policy while maneuvering by the Soviet Union's ambassador (John Banner) signals Cold War intrigue, all captured in Robert Surtees's crisp black-and-white photography. Meanwhile, MacMurray emerges as the polished politician as Kisses for My President delivers a kiss-off to the first woman President with a rushed, contrived, egregious ending that says a woman's place is indeed in the house—just not the White House.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The American President (1995)

The American President (1995)

Directed by Rob Reiner. Written by Aaron Sorkin.

Speaking of unprecedented, how would the public—and the media that shapes public perception—react to a sitting president, in the television era, who begins dating? The delightfully savvy romantic comedy The American President explores this intriguing question as President Andrew Shepherd (Michael Douglas), a widower with a bright, sassy teenage daughter (Shawna Waldron), begins to date attractive environmental lobbyist Sydney Ellen Wade (Annette Bening)—which then attracts the nation's scrutiny including that of conservative Senator Bob Rumson (a chops-licking Richard Dreyfuss), who attacks their morality as part of his quest for his party's presidential nomination.

Sorkin's superb screenplay displays an absolutely contemporary grasp of personal and political issues, but his sharp, snappy dialogue harkens back a half-century to the smart comedies of Howard Hawks and Preston Sturges while embracing the idealism of Frank Capra's inspirational best—check Shepherd's climactic press-conference speech for proof—heralding what Sorkin would develop with The West Wing.

True, too much of that dialogue can become glib, and you have to pay attention to the business about the crime and environmental bills that become contentious between Andrew and Sydney, but Douglas and Bening sparkle, singly and together, while backlit by a colorful entourage that includes Martin Sheen as the sage, supportive chief of staff (a role for Sheen later upgraded to president himself in The West Wing); Michael J. Fox as the George Stephanopoulos-like speech writer; David Paymer as the sardonic numbers-cruncher; and Anna Deavere Smith as the high-strung press secretary.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Lincoln (2012)

Lincoln (2012)

Directed by Steven Spielberg. Written by Tony Kushner.

Turning now to actual personages, Spielberg's mission to be the Baby Boomers' vivid if conventional historical tribune continues with Lincoln, although he wisely avoids hackneyed biography of the iconic 16th president by adopting Kushner's august script chronicling Republican Abraham Lincoln's (Daniel Day-Lewis) efforts to get the Thirteenth Amendment passed in the House of Representatives in early 1865. That amendment eventually outlawed slavery, reinforcing Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and, indeed, one of the reasons for the Civil War, although he faces challenges to getting the amendment passed even with the Union sure to win the war.

Despite a majority Republican House and support from Secretary of State William Seward (David Strathairn) and influential abolitionist Congressman Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones), Lincoln must rally support from across the aisle while assuaging both his son Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who wants to join the army, and his wife Mary (Sally Field), who won't forgive him if Robert is killed.

Kushner's dialogue exhibits a little too much period affectation while Spielberg cannot resist an extended denouement that, inevitably, touches on Lincoln's assassination and legacy. Still, Spielberg's framing and pacing rightly makes Lincoln an epic—even John Williams's score cannot overwhelm the narrative—with Day-Lewis's tremendous portrayal of Lincoln bringing the entire film into sharp focus as Lincoln's broad strokes, safe for all historical and political sensibilities, grandly and without controversy reinforce that old schoolyard generality: "Lincoln freed the slaves."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Sunrise at Campobello (1960)

Sunrise at Campobello (1960)

Directed by Vincent Donehue. Written by Dore Schary, adapted from his eponymous play.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt became one of America's greatest presidents by overcoming a handicap that was crippling not only physically but potentially politically had he not skillfully harnessed it to his advantage, as demonstrated at the climax of Sunrise at Campobello. Set between 1921 and 1924, Schary's labor of love Campobello depicts FDR (Ralph Bellamy), recently defeated as the Democrats' 1920 vice-presidential candidate, struggling with the paralysis that had struck him down while vacationing with his family, including wife Eleanor (Green Garson), on New Brunswick's Campobello Island. Early scenes of the initially-stricken Roosevelt veer between saccharine and melodrama as Bellamy and Garson seemingly overplay the Roosevelts' distinctive blue-blood accents.

Then Hume Cronyn's Louis Howe, FDR's key early advisor, catalyzes Donehue's workmanlike framing as Franklin gains strength—and Eleanor, domestic and timorous, gains confidence as she becomes Franklin's external emissary, delivering speeches and developing her own political acumen, as Franklin must eventually make his own crucial speech. Campobello exhibits its period politesse—the Roosevelts' relationship is storybook, the children are properly well-behaved—but both Bellamy and Garson, spurred by Cronyn's droll tartness, coalesce into the budding icons Franklin and Eleanor both became as Franklin's interactions with Governor Al Smith (Alan Bunce) and especially political gadfly Lassiter (David White) hint at FDR's incipient greatness.

![]()

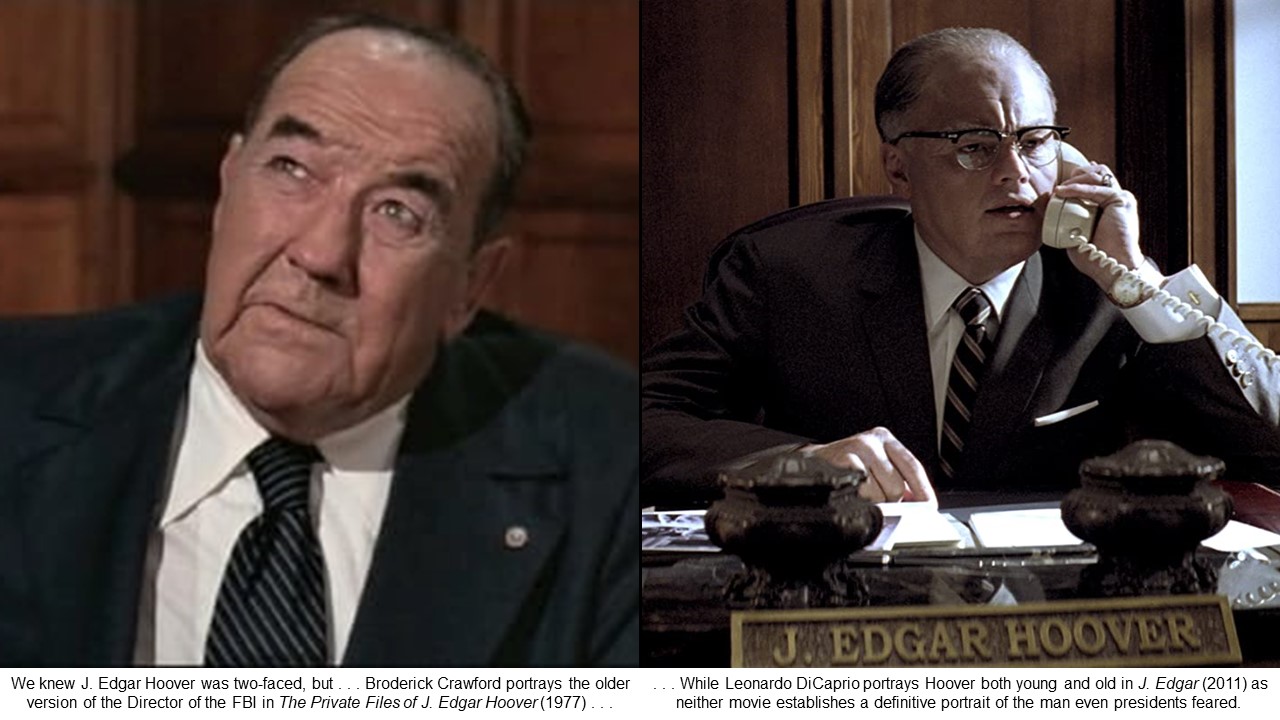

![]() The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977)

The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977)

Written and directed by Larry Cohen.

From 1924 to 1972, J. Edgar Hoover served as the obsessive, autocratic, ruthless Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover, released at the height of 1970s investigations into Vietnam, Watergate, and other governmental malfeasance, functions as a distilled exposé of those revelations that often displayed Hoover's fingerprints on them. However, in his attempt at a sweeping look at 20th-century American history through the lens of Hoover's FBI, Cohen's reach exceeds his grasp: Not only does he have too many targets to shoot at, but he adopts a lurid tone—trumpeted by Miklós Rósza's hyperbolic score—further hampered by the joint schizophrenia incurred by having James Wainwright and Broderick Crawford portray, respectively, the young and old Hoover.

Nevertheless, Cohen pulls no punches with unsparing vignettes illuminating Hoover's various crusades against, among others, immigrants, communism, organized crime—at least initially—and the civil rights movement, particularly Martin Luther King (Raymond St. Jacques), as he compiled compromising dossiers on individuals, often focusing on their sex lives—all while being a "confirmed bachelor" with a suggestively close relationship to FBI Associate Director Clyde Tolson (Dan Dailey). Amidst this overstuffed narrative, the thread involving Hoover's antagonistic relationship with Attorney General Robert Kennedy (Michael Parks), detailing Hoover's quest for power, stands out best and illustrates how Cohen should have selected just a few Private Files and not them all.

![]()

![]()

![]() J. Edgar (2011)

J. Edgar (2011)

Directed by Clint Eastwood. Written by Dustin Lance Black.

For a half-century across the heart of the American 20th century, Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover stood at the center of public life: he built, maintained, and often overextended the nation's premier domestic law-enforcement agency, holding political figures in thrall to him, and even inflaming the cultural imagination (The F.B.I. television series, which was stage-managed by the Bureau), while fending off speculation that he was gay. In J. Edgar, Eastwood and Black attempt to examine the personal and public faces of Hoover but rarely dive beneath the surface and, crucially, are not able to put Hoover into a definitive historical or popular context.

As Hoover, a compelling Leonardo DiCaprio holds the center of J. Edgar, but the film itself lacks a center, specifically, examination of Hoover's demons and how they impacted American society. Not helping is an elliptical, looping narrative that juxtaposes events from throughout the decades: The Palmer Raids at which Hoover cut his teeth while still living with his mother Annie (Judi Dench), the investigation of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping that established the FBI, and—all too briefly—Hoover and the FBI's counterintelligence role in the civil rights and antiwar movements, particularly Hoover's pronounced animosity toward Martin Luther King, Jr.. Ultimately, though, Eastwood and Black cannot find the spark to ignite the tinder they've gathered. J. Edgar Hoover's legacy was larger than life, but J. Edgar regretfully scales it back.

![]()

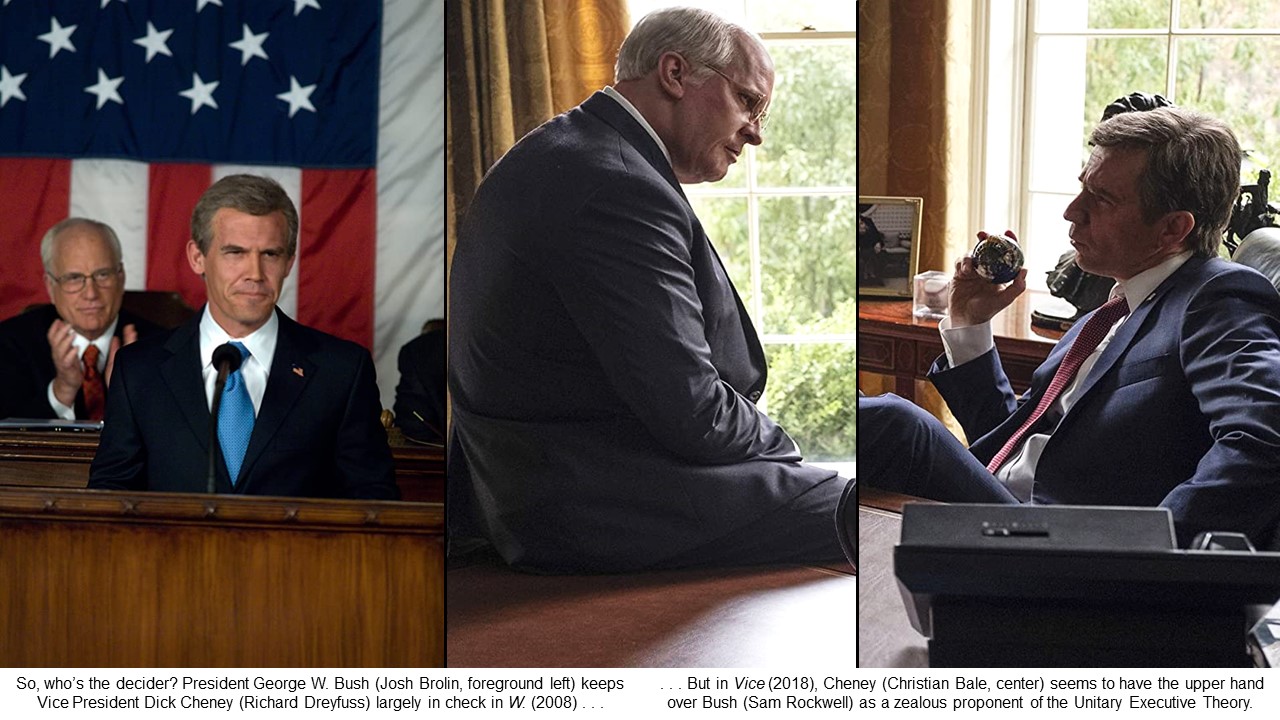

![]() W. (2008)

W. (2008)

Directed by Oliver Stone. Written by Stanley Weiser.

You might well expect Stone to take an antagonistic approach to the legacy of George W. Bush, but Weiser's conspicuously underwhelming script delivers an oddly hagiographic biopic with W. and its scattershot, elliptical path to Bush's becoming a president whose two terms were defined by the September 11, 2001, terror attacks and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that ensued from them. W. spans Bush's life from college wastrel to born-again reformed alcoholic to politician called by God in a non-linear narrative that not only lacks definition but fails to be definitive.

Josh Brolin performs yeoman service as Dubya, yet his portrayal, straddling imitation, parody, and conviction, informs most of the other performances—often it's difficult to tell if W. is supposed to be a put-on or if Stone and his cast are even aware of that effect. Furthermore, W. has no closure—it simply applies newspaper-thin coverage to too much territory. Moreover—and shockingly for Stone—there are no politics here, only shallow sound bites save for Dick Cheney's (Richard Dreyfuss) Machiavellian outline for renewed American imperialism that comes much too late to establish any context—or content. Elizabeth Banks, Ellen Burstyn, James Cromwell, and Dreyfuss are the best supporters in a cast chosen for their resemblances to actual players surrounding Dubya as W. makes him an empty suit hardly misunderestimated.

![]()

![]()

![]() Vice (2018)

Vice (2018)

Written and directed by Adam McKay.

Speaking of Machiavellian, Dick Cheney became the most influential vice president in modern American history, truly the power behind the throne with two crucial advantages—one, the vice-president receives little scrutiny as a "ceremonial" post; two, Cheney has always been a laconic enigma; thus, he has remained largely incognito. McKay attempts to solve Cheney's mystery in Vice, and while Christian Bale effects a remarkable depiction of Cheney, Vice lacks incisiveness, its flashy but scattershot delivery biting off more than it can chew as McKay struggles to use Cheney as a metaphor for the last fifty years of American governance, which has exacerbated economic disparity, perpetuated militarism, and, after 9/11, restricted civil liberties.

Snapped into focus by driven wife Lynne (Amy Adams), Cheney becomes an intern to Nixon-era Representative Donald Rumsfeld (a terrific Steve Carrell), who instills in Cheney a lust to secure and hold power through the Unitary Executive Theory, first as Gerald Ford's chief of staff, then as George H.W. Bush's defense secretary, and finally as George W. Bush's (Sam Rockwell) vice president, pushing for the 2003 Iraq invasion, which spurs the creation of Islamic State terrorists.

By casting his net wide, McKay's non-linear narrative becomes a series of shallow sound bites splashed onscreen by Hank Corwin's febrile edits and punctuated by McKay's audacious cinematic stunts—witness Dick and Lynne's mock-Shakespearean pillow talk, or the jokey false ending midway through—capped by self-conscious closing sequences that are already dating badly. Vice does little to illuminate or dispel Cheney's public image, riffing on obvious biographical points and leaving him incognito still.

Nixon's the One

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although not discussed in alphabetical or chronological order below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

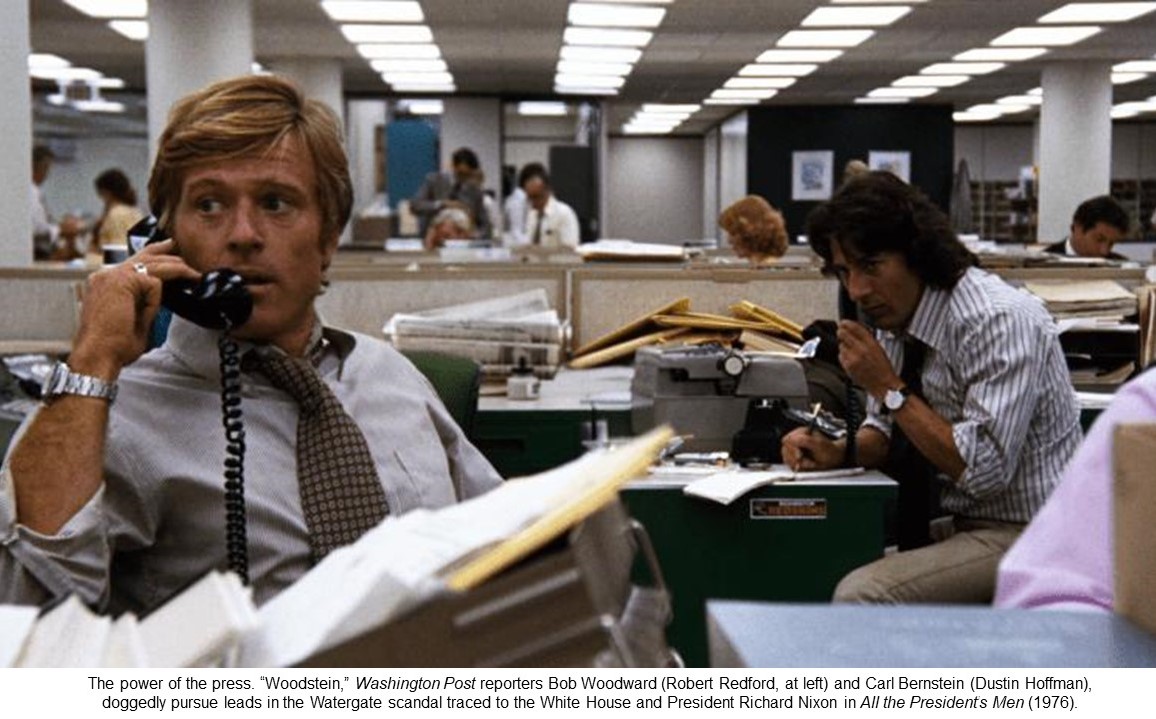

![]() All the President's Men (1976)

All the President's Men (1976)

![]()

![]()

![]() Dick (1999)

Dick (1999)

![]()

![]()

![]() Elvis & Nixon (2016)

Elvis & Nixon (2016)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Frost/Nixon (2008)

Frost/Nixon (2008)

![]()

![]() Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House (2017)

Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House (2017)

![]()

![]()

![]() Nixon (1995)

Nixon (1995)

Ah, Richard Nixon. The man we're still kicking around even a quarter-century after his death, a president whose imprint on the national consciousness was so singular that he deserves his very own section.

Growing up in a poor Quaker home in Southern California, Richard Milhous Nixon married Pat Ryan, became a lawyer, and served in the US Navy Reserve during World War Two before he began his political career in 1946 as a red-baiting Republican Congressman and Senator—he once described Helen Gahagan Douglas, his Democratic senatorial opponent, as "pink right down to her underwear." Then in 1952 he became Dwight Eisenhower's powerful and influential vice president groomed to become president himself in 1960 until John Kennedy, largely by positioning himself as even more anti-communist than Nixon, narrowly defeated him.

Following a defeat in the 1962 California gubernatorial race, Nixon infamously declared that, "You won't have Nixon to kick around anymore," and retired to private law practice, but in the tumultuous political year of 1968 Nixon returned to be elected as the 37th President of the United States, promising to end the Vietnam war ("peace with honor") and return law and order to the conservative "Silent Majority." Nixon scored foreign policy successes by opening relations with Communist China and furthering détente with the Soviet Union through arms-limitation talks, but he also widened the Vietnam war into Cambodia and oversaw a 1973 CIA-instigated coup in Chile.

Domestically, he battled inflation with wage and price controls and established both the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration—but he also unleashed the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Internal Revenue Service on his political opponents as the existence of a White House "enemies list" became known. That culminated with the June 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters in the Watergate hotel and office complex, which implicated Nixon when the burglars were quickly tied to the White House.

The Watergate investigations proceeded slowly and quietly—Nixon was still able to score a landslide re-election victory over Democratic candidate George McGovern in November—but Nixon's resistance to the investigations built toward impeachment charges of obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress fueled in part by revelations of a tape-recording system in the White House containing incriminating information on Nixon, including evidence of a "dirty tricks squad" sabotaging the McGovern campaign, which eventually forced him to resign in August 1974, the only president ever to resign while still in office.

With such a colorful résumé, you can see why we have a section devoted entirely to Tricky Dick. We begin with an overview of Nixon before delving into his signature association, Watergate, with both serious and satirical movies exploring this celebrated scandal, then ending on a curious historical footnote that straddles politics and pop culture.

![]()

![]()

![]() Nixon (1995)

Nixon (1995)

Directed by Oliver Stone. Written by Stone, Stephen J. Rivele, and Christopher Wilkinson.

Expecting a hit job on Richard Nixon from Stone? Admittedly, Nixon does not miss many of Tricky Dick's well-known dirty tricks—while insinuating others that are not so well-known—throughout his long political career, but thanks to Anthony Hopkins's quirky, oddly absorbing, but finally indefinite portrayal of Nixon, Nixon generates surprising if guarded empathy for the complex, cunning, contradictory, and ultimately needy man you loved to hate.

The overstuffed screenplay indulges that psychodrama, rooted in his humble, tragic Southern California upbringing and perpetuated in his sometimes-contentious marriage to Pat Ryan (an effective if underused Joan Allen), while using the Watergate scandal, Nixon's downfall, to anchor Stone's non-linear narrative. Beginning as a staunch anti-communist Congressman, Nixon eventually became Dwight Eisenhower's vice president, positioning him to be president in 1960 until upset by John Kennedy. Finally attaining the Oval Office in 1968, Nixon's quest for power and control delivers the inevitable hubristic comeuppance he is unable to accept.

Similarly, Stone's kinetic, frenetic pace delivers an overwhelming blizzard of images, personages, and events that defy viewers to process them adequately even within Nixon's mammoth running time. Fortunately, a formidable cast, particularly Paul Sorvino (portraying Henry Kissinger) and James Woods (H.R. Haldeman) as some of the president's men who add ruthless realpolitik, mitigates Stone's sprawl and inability to focus effectively as Nixon still has Nixon to kick around some more.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() All the President's Men (1976)

All the President's Men (1976)

Directed by Alan J. Pakula. Written by William Goldman, adapted from the eponymous book by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward.

Although the end result of the Watergate investigation was spectacular—the resignation of President Richard Nixon and the criminal convictions of several of his staff—the mechanics of the initial investigation was painstakingly methodical, even plodding, as was the non-fiction account All the President's Men by Washington Post reporters Woodward and Bernstein. Thus, it is remarkable that the investigation by Woodward (Robert Redford) and Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman), which starts with a break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate office complex in June 1972, manages to sustain interest and even suspense regarding mundane and now-archival material that mirrors faithfully actual persons, events, and timelines in this powerful film adaptation.

"Woodstein" quickly discover the burglars' apparent connections to the Nixon White House, but with little to go on the reporters slowly piece together how the burglars received funds from the Committee to Re-Elect the President. Even with Woodward's notorious anonymous source Deep Throat (Hal Holbrook), who famously advises Woodward to "follow the money," they still have to convince Post Executive Editor Ben Bradlee (Jason Robards) that they have a story while battling the rival New York Times for scoops even as the continuing story, a dull daisy-chain of names linked by money connections, barely engages the public. Hoffman's Bernstein is pushy, almost impetuous, while Redford's Woodward is sober and meticulous, but their joint determination provides the narrative thrust, effectively framed by Pakula and cinematographer Gordon Willis, whose visuals provide the tense, dogged atmosphere in the lucid and engrossing All the President's Men.

![]()

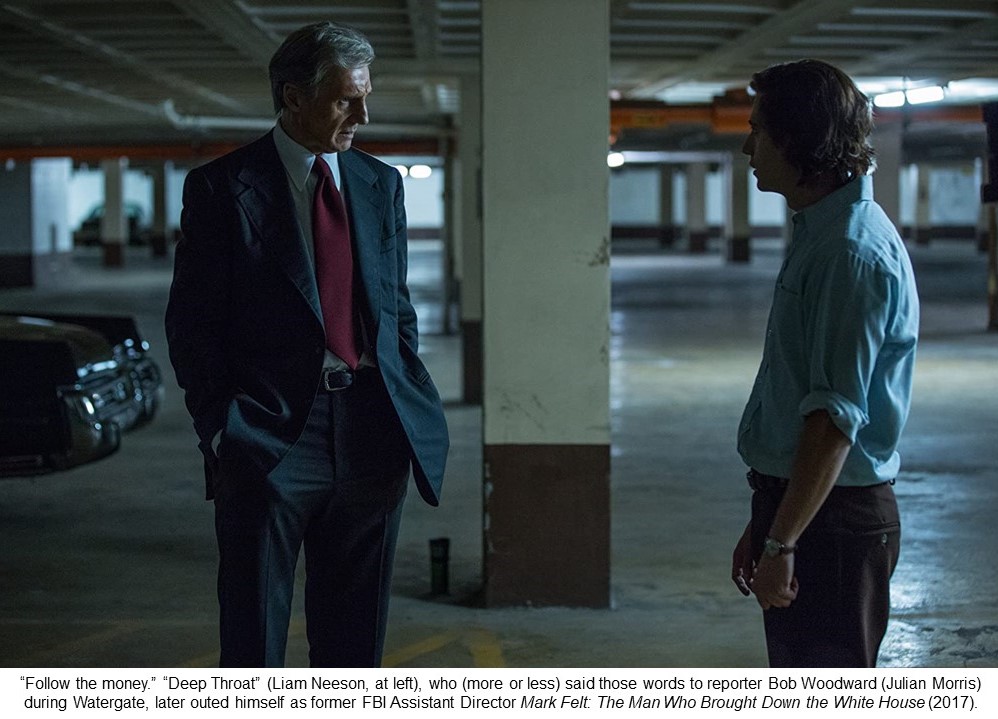

![]() Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House (2017)

Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House (2017)

Written and directed by Peter Landesman, based on the book A G-Man's Life by Mark Felt.

Even after President Richard Nixon's 1974 resignation resulting from his role in the Watergate break-in scandal, one enduring question remained: Who was "Deep Throat," the government insider whose anonymous tips to reporter Bob Woodward helped the Washington Post connect a "third-rate burglary" attempt at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate office complex to the Nixon White House, which tried to cover up its involvement.

In 2005, Mark Felt, a former Associate Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, revealed that he had been Deep Throat, with Landesman's oversized title alone attempting to thrust Felt, portrayed with imposing gravitas by Liam Neeson, into heroic status as the architect of Nixon's historic downfall. Expecting to succeed FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover following his 1972 death, loyalist Felt instead sees Nixon insider L. Patrick Gray (Marton Csokas) appointed to control the FBI's investigation into the Watergate break-in, to Felt's chagrin—although, ironically, Felt himself is later prosecuted for ordering break-ins of radical groups.

Landesman attempts to portray complex events through Felt's eyes, but he struggles to keep that many plates spinning without their crashing while penning conspicuously expository dialogue uttered by a parade of supporters including Julian Morris, portraying Woodward, and Tom Sizemore, portraying former FBI agent William Sullivan, a Hoover critic at loggerheads with Felt. Daniel Pemberton's quietly insistent, naggingly persistent score inflates the clandestine melodrama and stagy portentousness as Mark Felt broadcasts importance but without convincing relevance.

![]()

![]()

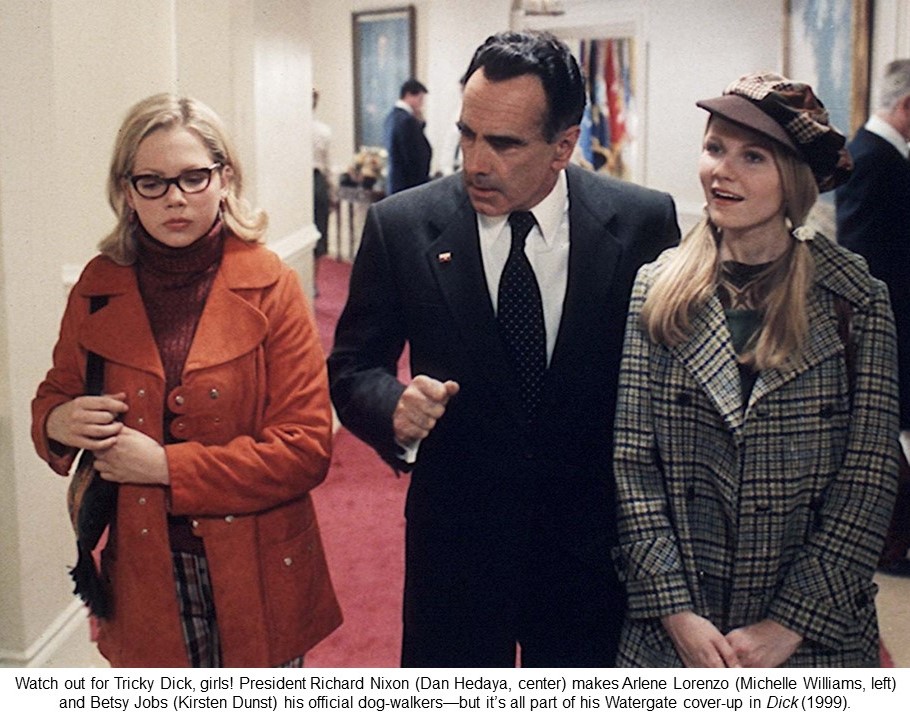

![]() Dick (1999)

Dick (1999)

Directed by Andrew Fleming. Written by Fleming and Sheryl Longin.

But wait a minute—what if Mark Felt wasn't Deep Throat? Fleming and Longin's broad political satire Dick (made before Felt's 2005 admission) offers another tongue-in-cheek possibility in their waggish, if ultimately middleweight, reimagining of the burglary scandal that ended Richard Nixon's (Dan Hedaya) presidency that deftly blends events and personalities to provoke knowing guffaws. However, Dick nearly stalls before it begins as a Larry King-like television interviewer (French Stewart) attempts to learn from bickering, childish Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward (Will Ferrell) and Carl Bernstein (Bruce McCulloch) the real identity of Deep Throat.

Fortunately, Kirsten Dunst and Michelle Williams appear to shift Dick into cruising gear. While living at the Watergate, high schooler Arlene Lorenzo (Williams) and her best friend Betsy Jobs (Dunst) stumble upon the burglary. Then, on a school tour of the White House, they are recognized, and, to keep them under surveillance, Nixon offers to make them White House dog-walkers to First Dog Checkers (Brunswick). Lo, the pair's lives intertwine with Tricky Dick's through marijuana, Vietnam, and arms control with the Soviet Union until they discover incriminating Watergate evidence—and when Arlene's crush on Dick sours, well, we can guess the rest of the story.

Dick plays like sketch comedy writ large with its inevitable peaks and valleys, but twin peaks Dunst and Williams are adorable—animated, engaged, resourceful—with Hedaya slyly skirting the temptation to caricature Tricky Dick as the soundtrack's parade of period-appropriate AM-radio hits drives Dick to its heartwarming, hilarious closing shot. At least now we know what was on that tape with the eighteen-minute gap.

![]()

![]()

![]()

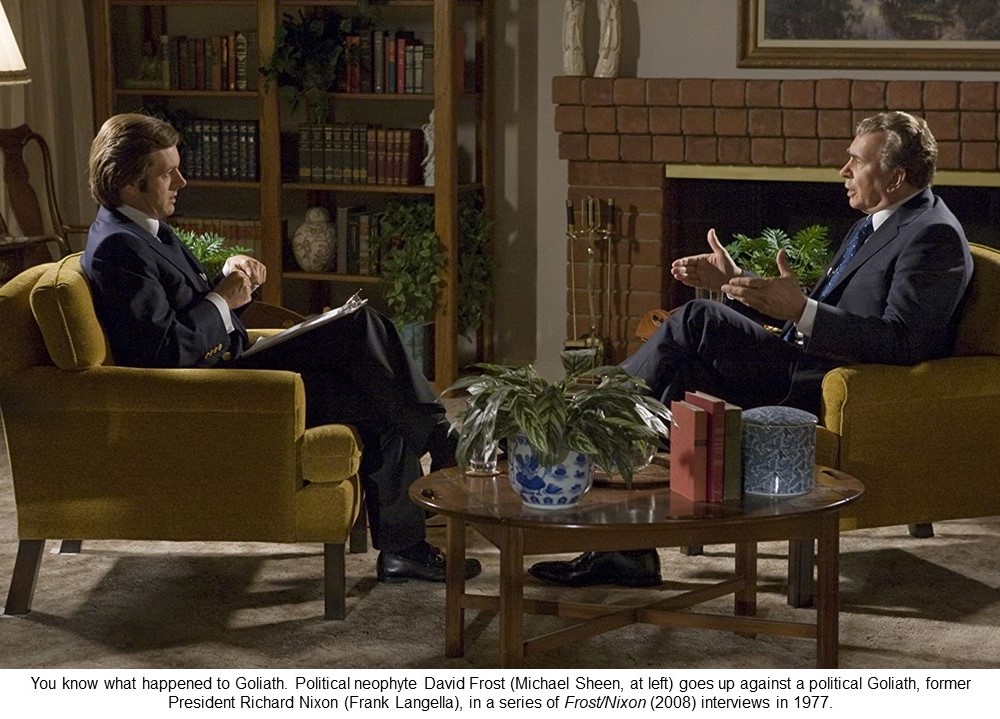

![]() Frost/Nixon (2008)

Frost/Nixon (2008)

Directed by Ron Howard. Written by Peter Morgan, adapted from his eponymous play.

With a potential to become a real-life farce, Frost/Nixon, which dramatizes the landmark television interviews English presenter David Frost (Michael Sheen) conducted with Richard Nixon (Frank Langella) following his 1974 resignation, suggests initially that Frost, known only as a light-entertainment reporter, will be routed by the far more politically-savvy Nixon, expecting to shore up his reputation on such easy pickings. Morgan's incisive script, admittedly laced with dramatic license, nevertheless examines the dynamics behind Frost's attempts to fund and stage the interviews, not to mention Nixon's buy-in, with Sheen assuming a foppishness that disguises Frost's ambition while Langella adopts Nixon's mannerisms without outright imitation.

By 1977, Frost had managed to launch the project—a neophyte David confronting Nixon's political Goliath, according to Morgan's part-narrative, part-reflective script. As the interview tapings progress, Nixon seems in command of the proceedings, to the dismay of Frost's research team (portrayed by Matthew Macfadyen, Oliver Platt, and Sam Rockwell). Then Nixon makes a boozy late-night call to Frost—an obvious plot twist that did not actually occur—that spurs Frost to redouble his efforts for the final interview segment about Watergate, which prods Nixon into a shocking admission. Never an incisive director, Howard, with the script and the performances of Langella and Sheen driving his story, accents effectively with lively pacing and framing, making Frost/Nixon one of his most satisfying films, keeping you tuned in throughout.

![]()

![]()

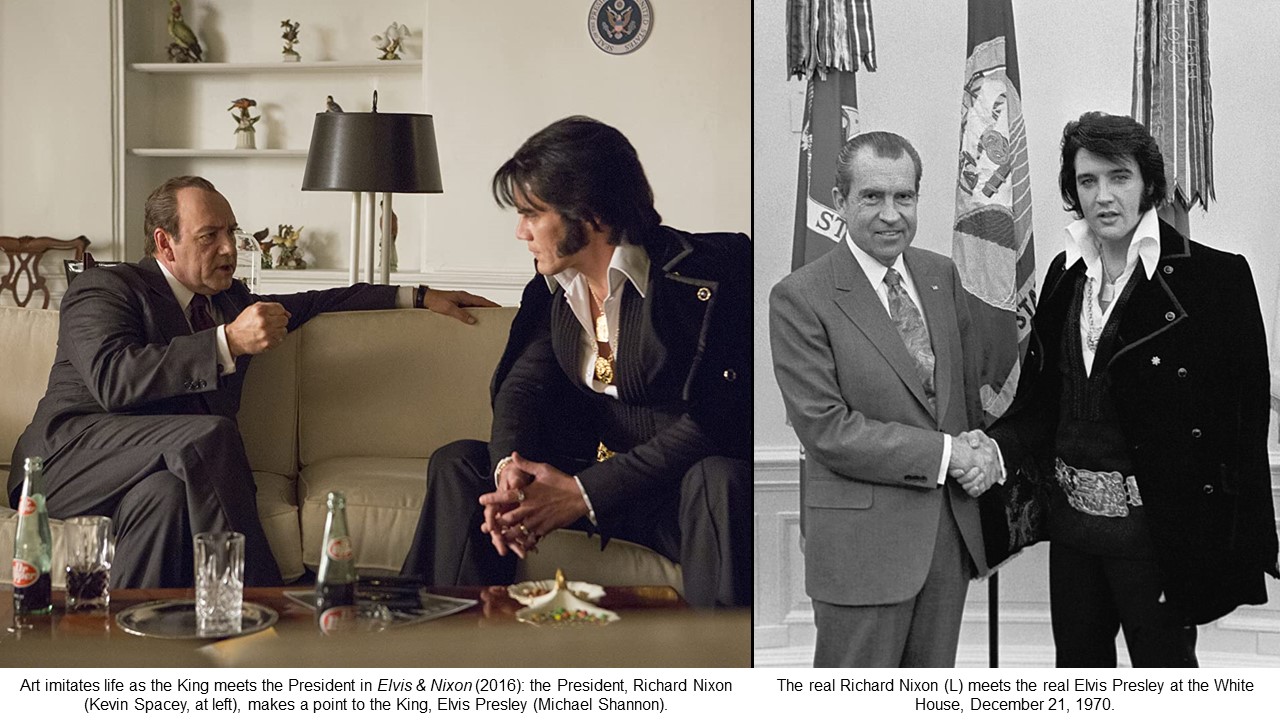

![]() Elvis & Nixon (2016)

Elvis & Nixon (2016)

Directed by Liza Johnson. Written by Cary Elwes, Hanna Sagal, and Joey Sagal.

Finally, light entertainment returns as pop culture meets politics in a decidedly offbeat manner in Elvis & Nixon, which would seemingly be fanciful Boomer wish-fulfillment were it not based on an actual December 21, 1970, encounter between the King, Elvis Presley (Michael Shannon), and the President, Richard Nixon (Kevin Spacey), in this amusing but slight vignette. And it's pop culture that rules the day as this true-life shaggy dog is told primarily from the Elvis camp's perspective, with Elvis crony Jerry Schilling (Alex Pettyfer) the fulcrum between the King's desire to serve as a "Federal Agent at Large" in the Nixon Administration's "War on Drugs," and White House staffers Egil Krogh (Colin Hanks) and Dwight Chapin (Evan Peters) who try to convince their boss, Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman (Tate Donovan), and then their über-Boss, Nixon, that this could help court the youth vote.

Not surprisingly, the actual meeting is anti-climactic, with director Johnson opting for a farcical recounting as Spacey, deftly underplaying Nixon's too-easily-caricatured mannerisms, nevertheless winds up looking buffoonish while the hip counterculture seems to put one over on the uptight Establishment—or does it? Shannon captures Presley's quietly bizarre behavior during this era without much insight into what produced it against the soundtrack's classic rock and soul songs as Johnny Knoxville and Tracy Letts provide support. Engaging and economical, Elvis & Nixon is ultimately Baby-Boomer ephemera.

Comments powered by CComment