Index

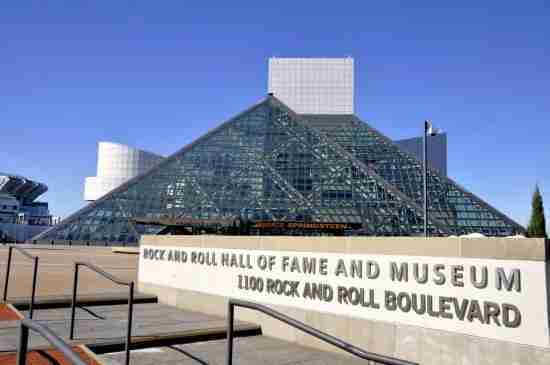

Issue Three: The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Is Expansive and Inclusive

Now we get to the heart of why the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame seems to suck for so many people and why its suckage may never be remedied.Because there is no standard definition of rock and roll, the Hall is expansive, meaning that an ever-increasing range of styles and genres keep getting added to the musical form labeled "rock and roll." And because there are no universally objective criteria for evaluating legacy, the Hall is inclusive, meaning that evaluating a candidate for the Hall becomes a subjective judgment with no threshold or parameters.

Recall poor Charlie Gillett's attempt to define "rock and roll"—and he had only to do so for about a decade-and-a-half's worth of music. Yet in that time, rock (and soul) had already begun to evolve from its roots in blues, rhythm and blues, folk, and country and western into ever more eclectic styles, not only returning to those wellsprings to make them more pronounced and explicit (folk-rock, blues-rock, country-rock), but it had begun to incorporate other sources to produce art-rock or progressive-rock, jazz-rock, the Motown sound, Southern soul, psychedelic rock, and so on.

And those innovations in turn spawned even more styles, with funk, heavy metal, disco, and punk-rock being among the best-known sounds from the 1970s. And those styles spawned or combined (or even re-combined) to produce even more variants, each ranging even further afield from the "style of popular music that derives in part from blues and folk music and is marked by a heavily accented beat and a simple, repetitive phrase structure," to borrow from one of our previous dictionary definitions of rock.

Correspondingly, these ever-multiplying styles and genres (and sub-genres) found audiences that varied greatly in size, interest, and sponsorship so that a "cult" artist could sustain a career, and even prove to be influential on contemporary and subsequent artists, without needing to have hit singles, huge sales, or large-scale concerts. And as technology evolved and barriers to entry into the rock and roll industry were removed, even greater numbers of artists were able to reach and establish audiences.

Up until the 1980s, artists largely had to attract a major recording label that could produce and distribute their music, and then try to impress broadcasters, primarily radio stations, if they wanted to build an audience and sustain a career. As technology and alternative business models progressed, more artists found it easier to enter the field.

And this was a two-way street: Audiences became more sophisticated and more discerning, willing to support "underground" or "alternative" artists because they offered music that appealed to them more so than "commercial" music, which still had its audiences, but as the market of listeners expanded, so did the number of artists, now at many levels of popularity, to meet the growing demand.

By the 1980s, smaller labels began to act as "farm teams" for artists who could (and did) attract interest from major labels and thus also attract larger audiences (a classic example being R.E.M., which began as college favorites on I.R.S. before moving to Warner Bros. and mainstream success). And by the time the Internet Age began, the music business that had already undergone so many changes since the inception of rock music in the 1950s experienced another profound jolt: An artist creating professional-quality music in his or her own home could market it directly to the world on the internet through a number of online channels.

All of which suggests how increasingly difficult it is to establish, first, any objective evaluation criteria, but, second, how to apply it universally to an ever-increasing range of music grouped under the "rock" umbrella that operates on so many viable levels, from the superstar pop acts of today to the niche artist with a small yet loyal following, with artists at every point of this spectrum having the potential to influence the course of "rock" as it continues to progress. The music is truly inclusive.

So how can you hope to have a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame that can capture these ever-changing dynamics without becoming a haphazard mess subject to various biases, prejudices, and limitations?

To put this into perspective, let's contrast this with the nature of the Halls of Fame for the Big Four major American team sports. Once again, we are not contrasting, let alone comparing, the endeavors themselves—rock and roll music and each of the team sports—as they have so little in common beyond providing entertainment to spectators. But each uses the common mechanism of a Hall of Fame to preserve it history and to celebrate its legacy, and examining why the sports Halls of Fame are generally successful can help to illustrate why the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is not.

Contrasts with the Sports Halls of Fame

In truth, there is variance among the sports Halls of Fame. The Basketball Hall of Fame, more properly the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (named for basketball's inventor, Dr. James Naismith), is easily the most expansive of the four as it inducts both amateur and professional candidates not just from the United States but from around the world. So, while the National Basketball Association, the top-tier professional basketball league in the United States (with one Canadian team extant, the Toronto Raptors), is prominently represented, it is not the exclusive representative.

Similarly, the Hockey Hall of Fame is not exclusively dedicated to the National Hockey League, the top-tier professional hockey league in the United States and Canada, as it includes selected individuals with no NHL connections, although a common criticism of the Hockey Hall of Fame is that it is focused on the NHL to the general exclusion of other hockey leagues in North America and around the world.

However, both the Pro Football Hall of Fame and the Baseball Hall of Fame concentrate exclusively on their top-tier professional leagues—the National Football League and Major League Baseball (comprising the American League and the National League), respectively—barring any historical leagues that relate directly to the current structures.

In fact, consider how exclusive and restrictive is the Baseball Hall of Fame. First of all, when you walk into the Baseball Hall of Fame, you know what you're getting: baseball. That might sound obvious or even silly, but it means that you're not getting a sport that is similar to or derived from or that influenced or inspired baseball—cricket, softball, or rounders, for instance. Recall that at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, there is no standard definition of rock and roll.

And it is not just any baseball—it is Major League Baseball, the top-tier of American professional baseball. That means no youth or amateur leagues, no minor leagues, no independent leagues, and no international leagues. True, players in or to be considered for the Hall may have had experience with those other leagues, but those experiences have no impact on consideration of a candidate for the Hall except as part of the candidate's narrative.

This will prove to be more than simply theoretical when outfielder Ichiro Suzuki becomes eligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame in a few years' time. (I've written about Ichiro and the Hall twice, once in 2011, and again in 2016.) Suzuki was a superstar in Japan for nine years, with the Orix Blue Wave in the Nippon Professional Baseball League, before coming to the United States to play for the Seattle Mariners.

Last year, he reached the 3000-hit plateau in Major League Baseball, which, barring two certain examples, is practically a lock for the Hall of Fame. En route to 3000 Major League hits, Ichiro notched a safety that put him at 4257 hits when his hit totals from both NPB and MLB are combined, which led some to dub him the "all-time hit king of professional baseball." Not surprisingly, this provoked immediate backlash, not least from Pete Rose, who with 4256 hits is the all-time hit king in MLB history, and who noted that the caliber of play in the NPB is not the same as it is in the MLB and thus it is not a valid assertion.

While I agree with Rose and other like-minded persons, for our purposes here, look at what that suggests—a redefinition of "baseball" as it relates to the Hall of Fame, which is the problem that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame always faces. The issue isn't whether the Baseball Hall of Fame should expand, which is a valid discussion, but rather that the reason why the Baseball Hall of Fame is so successful is because its parameters are so narrowly defined. Suzuki's hits accrued in NPB fall outside those narrowly defined parameters.

And restricting those parameters even further, not only does a candidate had to have played in the MLB, he had to have played for at least 10 years; furthermore, he doesn't become eligible for the ballot until five years have elapsed since his retirement year.

But playing for at least 10 years does not automatically put a player on the Hall of Fame ballot—the player had to have had a notable enough career to be included on the ballot, which is the ballot that is voted on by the eligible members of the Baseball Writers' Association of American (BBWAA).

Once on the ballot, the player-candidate must receive at least 75 percent of the vote in order to be elected to the Hall of Fame—and he must receive at least five percent of the vote to remain on the ballot. Finally, and barring election or receipt of less than five percent of the vote, the player-candidate may remain on the BBWAA ballot for only 10 years—an even further restriction as that maximum length of time had been reduced from 15 years in 2014. If a player has not been elected to the Hall after 10 years, he is no longer eligible for the Hall unless he is nominated by a veterans committee that may vote him into the Hall with at least 75 percent of its vote.

Talk about restrictive and exclusive: A player who has been voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame first had to ascend through multiple levels of competitive play, possibly starting way back in Little League and other youth leagues before playing on high school or college teams, then generally entering the professional minor leagues with their own ascending levels before getting an opportunity to play in the Major Leagues. By that time, only an elite few have managed to make it that far. Then the player must perform well enough to stay in the Majors for at least ten years and earn a spot on a BBWAA Hall of Fame ballot, where he must still satisfy voting criteria just to stay on a ballot, yet still earn enough votes to be elected to the Hall of Fame before ten years have elapsed, at which time, if he is not elected, he might get a second chance on a future veterans committee ballot, which is far from guaranteed.

And to illustrate how exclusive are baseball and football, and to lesser extents hockey and basketball, keep in mind that there are limited opportunities for a player (a "performer") to play in that respective sport. There are 30 teams in MLB, 32 teams in the NFL, 30 teams in the NHL (expanding to 31 for the 2017-18 season), and 30 teams in the NBA. With each sport experiencing widening talent pools, competition for those limited number of roster spots becomes tougher, making it harder to keep a spot and thus establishing a Hall of Fame case.

Contrasting the Sports Halls of Fame with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

If you think that we've wandered far afield from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, remember that our point here is to contrast that Hall with the sports Halls of Fame, not to conflate rock and roll with sports but to illustrate the fundamental differences between how their respective Halls operate. I may have loaded the argument by using the Baseball Hall of Fame, which has the most rigorous (yet transparent) requirements for induction; yet the baseball Hall is considered to be the most prestigious of the sports Halls of Fame not simply because it is the oldest, serving the oldest of the four major team sports, but because it is the most stringent of the Halls.

But all of the sports Halls of Fame share, albeit to different degrees, a crucial fact: By the time each of the Halls prepares to determine inductees, all of them have been pre-screened and selected to be among the elite through the very nature of the endeavor: Within a universal and easily understood definition of the sport, using to a significant extent objective evaluation criteria that can be universally applied, the candidates are drawn from only the top ranks of the sport, and for baseball and football and to a large extent hockey those top ranks are even more narrowly defined.

To put this in the context of the issues facing the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, imagine that the Baseball Hall of Fame included candidates from not only baseball at all levels but from sports similar to baseball as they are now all grouped under the catch-all term "baseball." That is what it means not to have a standard definition of baseball. Then imagine that although all the various manifestations of "baseball" generate their own statistics, they cannot be compared to each other equally owing to the varying quality of play. That is what it means not to have objective evaluation criteria that can be applied universally.

In other words, can you imagine a Baseball Hall of Fame in which Hank Aaron and Babe Ruth stand equally with Mike Hessman, the all-time home run leader (433 home runs) in the American minor leagues, and with Buzz Arlett, whose former record Hessman broke by one home run? And although both Hessman and Arlett played some games in the Major Leagues, that isn't a fair comparison. Or is it?

Again we encounter the inherent nature of each endeavor, either sports or rock and roll music, which of course makes it useless to try to compare, or even contrast, them directly as they are so dissimilar. But each uses a Hall of Fame as its mechanism to preserve its history and celebrate its legacy, and to celebrate its legacy, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame uses the same process as do the sports Halls of Fame: Round up a collection of candidates every year, present that ballot of candidates to a panel of voters for their evaluations and decisions, count up the votes, and enshrine those candidates that pass the threshold for induction.

Nominating and Voting Processes for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Let's take a moment to outline how that process works—or doesn't—for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Determining which artists appear on an annual ballot falls to a nominating committee. Not only does the size of this committee vary from year to year, but who the members of the committee are is often an exercise in sleuthing although the team at the Future Rock Legends website does a yeoman service in identifying those members—and it should be no surprise that the nominating committee is weighted heavily with individuals with past or current affiliations with Rolling Stone magazine and thus with Jann Wenner, the driving force behind both that magazine and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation, the organization that administrates the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Each member of the nominating committee gets to nominate two or three artists for a preliminary ballot (depending on the source cited), which the committee then winnows down to a manageable ballot of between 15 to 20 candidates, more or less—and you should be getting the idea that not only is the process not clearly defined but that it is not even transparent.

Nevertheless, that ballot is then sent out to the voters, who are industry professionals including "every living Rock Hall inductee," with a potential pool that numbers in the hundreds, again depending on the year and the source. That voting pool in turn casts its ballots, and the candidates with the highest vote totals become the latest Hall inductees, with the class usually numbering five. Or six. Or occasionally seven. Or—guess what? Is this clearly defined too? And do we even get to know what the voting totals for all of the candidates were in a given year?

At least candidates do get elected, but as we have seen, whether those candidates meet anyone's definition of "rock and roll" or anyone's criteria for a "Hall-worthy" candidate is a wide-open question.

By contrast for the sports Halls of Fame, the baseball and football Halls especially, their candidates have already undergone years of rigorous pre-screening before they even join the pool of potential candidates in the top tier of their sport. That is inherent in the endeavor itself, which is premised on competition so that the best keep rising until they reach the top tier. Furthermore, the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame at least keep their charter narrowly focused on that top tier.

Not so with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as rock music, like any musical form, is an aesthetic endeavor that affects the culture that spawns it in ways that cannot be measured—or even predicted. True, hot prospects enter the top tiers of the Big Four team sports every year, and some may succeed while others fail. But even when "phenoms" enter the top tier—Wayne Gretzky, Michael Jordan, Babe Ruth—they do not fundamentally change the nature of their sport. Even Babe Ruth, who did revolutionize offensive strategy in baseball by establishing the primacy of the home run, still played a game defined by almost all of the same rules, protocols, and dimensions as when he started, while his innovation, which coincided with the advent of the Live Ball Era of baseball, is nearly a century old now.

The Changing, Variable Nature of "Rock and Roll Music"

On the other hand, rock and roll music is constantly evolving and expanding, pushing into directions that often defy prediction, but when they occur, they execute another quantum leap from the origins of the music, "a type of pop music originating in the 1950s as a blend of rhythm and blues and country and western," as we've seen it defined.

Moreover, an artist does not have to have "played," or have been on the rock-music scene, for very long, or to have even been a "top-tier player," in order to have made an impact significant enough to have altered the course of the music.

Bill Haley and His Comets put rock and roll on the map in the mid-1950s with four Top Ten hits including the immortal "Rock around the Clock," which eventually became a chart-topping single after its use in the 1955 Glenn Ford film Blackboard Jungle, and the song has long been considered a milestone not only in rock and roll history but in pop culture overall. Haley was soon supplanted by Elvis Presley, who supplied the raw sexuality that the cherubic Haley could not, but Haley and his Comets brought rock and roll into the popular consciousness, thus paving the way for Presley. (Haley and various permutations of his band continued to perform as a nostalgia act for many years after their brief heyday, and in fact had begun as a Western swing band in the early 1950s, typifying the "country and western" influence we've seen in definitions of rock music.) Haley was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, and in one of those Band-Aid fixes the Hall has tried during its existence, several of his Comets were inducted a quarter-century later, in 2012.

The Sex Pistols were not the first punk band, nor were they even the best, but during their brief mid-1970s existence they managed to crystallize the burgeoning punk revolution with their attitude, behavior, and, not least, with a few signature songs that defined this brash, inchoate rebellion. And in true, albeit predictable, fashion, this Johnny Rotten-led outfit rejected its induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006, calling the institution and indeed rock and roll a "piss stain" next to the Sex Pistols. Maybe they were right?

Although it wasn't the first gangsta-rap act, N.W.A. established itself as the definitive one, and in the process it changed the course of hip-hop and by extension "rock and roll" as by the 1988 release of N.W.A.'s album Straight Outta Compton (Ruthless/Priority), hip-hop was indisputably a significant component of popular music. The group, scratching for success prior to the album's release, was soon defunct as its various members, most notably Ice Cube and Dr. Dre, split for solo careers, but during its short span it helped to shape the course of popular music; N.W.A. was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2016.

While Bill Haley and His Comets had a long career that predated the "birth" of rock and roll by the mid-1950s, their window of influence was small, coinciding with the phenomenon's initial burst of popularity—which of course they helped to establish—but, as with events in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang, the music began to experience quantum jumps in development very quickly, and their style of rock and roll (or perhaps "rock 'n' roll" as Charlie Gillette would have it) was soon superseded although they continued to play it for years afterward as a popular nostalgia act. On the other hand, the Sex Pistols seemed engineered for quick self-destruction, and N.W.A. also sundered relatively quickly although a couple of its individual members proceeded to have significant (and lengthy) solo careers.

Furthermore, just using these three examples illustrates how much "rock and roll" had evolved in less than four decades, to the point that it is difficult to find any similarities in Bill Haley, the Sex Pistols, or N.W.A. The Sex Pistols, like many punk bands, may have returned to a simpler musical approach—that "heavily accented beat and a simple, repetitive phrase structure" of one of our dictionary definitions above—but they had an abrasiveness, both musical and lyrical, scarcely conceivable in Haley's day. Likewise, N.W.A. had journeyed very far afield from the "soul" and "R&B" of pioneers Ray Charles and even James Brown, whose own musical approach underwent several transformations including early hip-hop.

Bill Haley and His Comets getting wild 'n' woolly in the 1950s as a seminal influence on rock and roll. But how much relation do they have . . .

. . . To N.W.A., a seminal influence on hip-hop nearly four decades later? Do these two acts really belong in the same Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

The point is that although these artists, composed as they were at the time of their critical influence, existed for only a relatively brief time (figuratively speaking for Haley and His Comets), but in that time they effected a change in the course of the music that has lived much longer than the artists did themselves.

Another factor to consider is that unlike the team sports, performing within an endeavor predicated on competition that drives ever-increasing excellence resulting in "performers" who, by the time they ascend to the top tier of their sport, are similarly top-tier players, rock and roll artists do not have to be the "best" in their craft to make a significant impact.

Certainly some level of technical competence is necessary in the overall presentation, although that doesn't mean it has to be the performers—remember Milli Vanilli? Conversely, technically adept performers are not guaranteed to be successful, which only underscores the serendipitous nature of rock and roll—what becomes popular or influential can be a sound, a feeling, a turn of phrase, even an attitude, that cannot be measured or quantified, and that does not have to be among the "best" of its kind, with "best" again being a relative and subjective judgment.

All of which speaks not only to the expansive nature of rock and roll, but also to its emotional and aesthetic essence. At the risk of belaboring this point, we have spent considerable time elaborating differences between the nature of evaluating team sports and the nature of evaluating rock and roll; this is not to contrast, let alone compare, the two endeavors but to illustrate that because each endeavor uses the same mechanism to preserve its history and to celebrate its legacy, a Hall of Fame, the sports Halls of Fame tend to be much more successful at determining legacy because they are restrictive and exclusive (albeit to varying degrees) while the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is expansive and inclusive.

Simply put, the sports Halls of Fame, which, again, have a distinct definition and objective evaluation criteria that can be universally applied, additionally have a much smaller pool of potential candidates from which to draw.

This is not true of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There is no standard definition of "rock and roll." There are no objective evaluation criteria that can be universally applied to its candidates. As the music evolves, the already-expansive definition of "rock and roll" continues to expand, and because the significance of an artist's impact does not necessarily correspond to even broad definitions of technical or artistic "excellence"—recall that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame lists "unquestionable musical excellence" as a mandatory condition but its descriptors are broad and subjective—the range and scope of the candidates under consideration for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame are enormous.

Is it any wonder that no one is satisfied with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

And while it is too easy to criticize the Hall for its selections or its non-selections, as people bitch equally about who has been inducted as about who has not been inducted, we should also realize that (with apologies to Shakespeare) the fault lies not in our rock stars but in ourselves.

Biases, Prejudices, and Limitations

As we noted above, ask 100 persons for a definition of "rock and roll" and you'll get 100 different answers, and those are likely to be examples of artists or even genres that the person considers to be "rock and roll" and not an overall description of "rock and roll" itself. And in fairness, we have explored in detail how expansive and elusive that definition can be.But that expansiveness pinpoints a fundamental shortcoming: We cannot know all that "rock and roll" entails unless we learn it—and that is no small task. Rock and roll has existed under that label for six decades, and it has evolved, and continues to evolve, all during that time. Unless you are an industry professional, or an amateur whose interest in rock and roll borders on the obsessive, you cannot hope to develop a comprehensive understanding of all that gets grouped under the umbrella of "rock and roll." And if you don't have that understanding, how can you expect to be able to evaluate the current inductees in, or prospective candidates for, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

The short answer is that you can't—which does not stop people from trying. Two common judgments leveled against the Hall are:

- The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame sucks because it has inducted Artist A.

- The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame sucks because it has not inducted Artist A.

- The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame sucks because it has inducted Artist A but not Artist B.

- The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame sucks because it has inducted Artist B but not Artist A.

This is an important point because music, perhaps more so than any other art form, engenders a personal, even intimate, relationship with it that arouses great feeling in us. Music touches us deeply.

Some years ago I hosted a "desert island" exercise in my workplace as a fun distraction from the usual grind, asking my colleagues to send me their top ten picks that I collated and distributed back to the department. People were enthusiastic and responsive when it came to favorite movies and television programs, but I noticed that the response for music wasn't as robust.

However, it wasn't because the prospective respondents were not as excited about music—rather, as a few of them admitted to me, music was such a deeply personal subject to them that it was hard for them to compile a list that was meaningful to them or, more typically, they felt reluctant about sharing with others a list that was very meaningful to them. Of course, there were those who couldn't wait to wax rhapsodic about their favorite music, and they did so in grand style. (I was one of those in the latter camp, and I even posted my top ten albums and top ten playlists on this site.)

In either case, though, that depth of feeling individuals have for their music is profound. Not surprisingly, then, that depth of feeling, that passion, gets translated into opinions about the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, often in the forms of argument just outlined above.

But look at how daunting it can be to try to formulate opinions about the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Rock and roll has no standard definition, and in fact the music keeps evolving and growing, making any definition ever more expansive. There are no objective evaluation criteria that can be applied universally. And because the music has grown so enormously over the last six decades, and seems likely to continue to grow, it is a Herculean task to try to assimilate it all, or at least to develop a strong enough understanding that enables an informed opinion. Yet that doesn't stop individuals from doing so because of the deep emotional bond they have with the music.

Are we doomed? Or, questioning my previous point, is this really our fault? On the latter point, it is not our "fault" in the sense that we have very little direct control over the nominating and voting phases of evaluating candidates for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame beyond having "voted" for them during their careers (or at least the segment of their careers that holds the most significance) by buying the records, going to the concerts, requesting that their songs be played on the radio, and so on.

True, in the last few years, the website for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has held a fan vote for each of the candidates on a given year's ballot. Visitors to the site can vote for up to five candidates, and that is not simply a popularity poll because the candidate who polls the most votes then has a ballot cast for him/her/them in the election. So, fans do have the barest modicum of influence on the election of candidates.

Now, does that influence make an actual difference? On the surface, the answer seems to be no, as it is one vote in a vote that can number in the hundreds. However, we do not know whether that popular vote echoes any consensus among the voting pool, or whether it exerts any influence on the voting pool.

Regarding the former point, whether we are "doomed" because the task of evaluation seems so daunting, it may be difficult, if not impossible, to remedy that—but it is possible to mitigate it.

A few years ago, the Hall's website used to have educational materials designed for teachers' instruction about rock music and the Hall of Fame to students that included material about music appreciation. That material is no longer available, which is unfortunate because it included a glossary of terms that contains some worthwhile definitions.

Among those definitions are those for aesthetic reflection and aesthetic judgment, which provide insight into the evaluation process—and that can prove to be valuable:

Aesthetic reflection: The act of becoming aware of one's own process of understanding and responding to the arts, and of examining how others respond to artistic expression.

Aesthetic judgment: The ability to form and articulate a critical argument based on aesthetic criteria.

Everyone who expresses an opinion on whether an artist belongs in the Hall of Fame follows those two concepts to arrive at that opinion. How well we formulate that opinion is a function of individual bias, prejudice, and limitations, with the correspondingly wide variance both in the range and in the quality of that opinion.

In essence, though, this is a two-stage operation. First, with aesthetic reflection, we sort out why it is that we respond favorably or unfavorably toward a certain form, style, or genre of music, and toward individual artists within those forms, styles, and genres, and even toward individual songs by that artist. Developing a conscious understanding of why we like or dislike different types of music, different artists, and different songs helps toward the next step of then being able to evaluate those types of music and those artists.

However, that is a big next step because that requires us to not only recognize why we like or dislike a musical type or musical artist, but to recognize why someone else may like or dislike a musical type or musical artist—and, more importantly, why that musical type or artist may be significant regardless of how we feel about it. Music appreciation is an intensely emotional experience, and it is overwhelmingly subjective, but it is possible to put our individual judgments into perspective, into a picture of the overall body of rock and roll music, to try to determine the significance of a musical type and a musical artist within that overall picture as the basis for evaluation.

This is the kind of thinking that can help us to evaluate more comprehensively, more thoughtfully, the choices the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has made and is considering making with each year's ballot; this is the kind of thinking that can help us overcome our biases, our prejudices, and our limitations.

However, that still requires us to accept the reality that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is expansive and inclusive, that it encompasses a diverse, even diffuse, body of music that, for better or for worse, has been grouped under an ever-growing umbrella called "rock and roll," and that even if we may have our preconceptions of what we consider to be "rock and roll," it may not match someone else's definition.

That is a tall order, and given the general dissatisfaction with the Hall, it does not promise to be one that is to be overcome any time soon. If anything, as the definition of rock and roll continues to grow, and as more, increasingly diverse artists become eligible for the Hall of Fame, the Hall can only become more expansive and more inclusive.

Does this spell the end of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Comments powered by CComment