Index

Is There Hope?

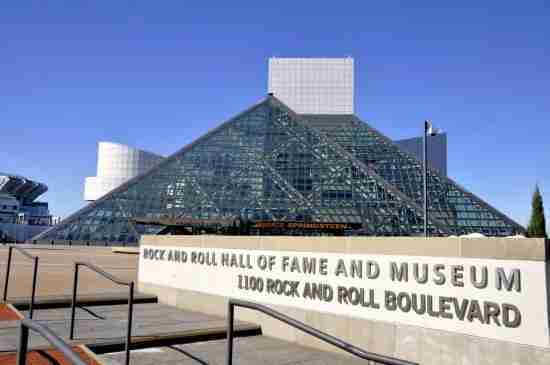

Yes, there is hope: I think the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame can be saved, but it will take a combination of the fundamental fixes and "Band Aid" fixes outlined above:"Smithsonian Institution." Whether it is a physical or virtual restructuring, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame must expand to encompass the tremendous growth and development of popular music since the mid-1950s, what I refer to rather inadequately as the Rock and Soul Era. Musical forms and genres such as hip-hop and heavy metal have spawned their own domains under the blanket term of "rock and roll," domains that have become too expansive to be managed by the Hall in its current state. A series of federated Halls of Fame similar to the many museums and galleries administered by the Smithsonian Institution can accommodate the current musical explosion that will only continue to grow in the years and decades to come.

Ballot Structure and Protocol. To adequately process the enormous number of potential candidates, more of whom are added every year, the Hall must institute a formal ballot structure and protocol to standardize the voting process. This would entail:

— Ballot criteria: Minimum voting percentage required to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, minimum voting percentage required to remain on a ballot, and the maximum number of years a candidate can remain on a ballot.

— Eligibility efficiency: Once candidates have met the 25-year eligibility period, they are put on the ballot. Given the tremendous volume, this will need to be staggered, or else refined through either a pre-screening or runoff process, but the haphazard, arbitrary method currently in place is chaotic and inefficient. Fans and voters—not to mention most especially the performers themselves—need to know that there is a standardized, ordered process in place instead of the current arbitrary, haphazard crapshoot.

— "Veterans committee" re-evaluation: A candidate who fails to gain election on the initial ballot process can be re-evaluated for induction at a future time. Given the tremendous throughput of an expansive, inclusive Hall of Fame, it is inevitable that the "ballot logjam" will eliminate candidates who may be otherwise worthy. Performance on that ballot can be used to select candidates for a re-evaluation committee, which could comprise the "educated, elite and sophisticated group of people" Jann Wenner and Rob Tannenbaum concede are better qualified to do this evaluation—although, noting the recommendations of Tannenbaum, Courtney E. Smith, and others, this must include a diverse membership and not just the white guys who are "older than the Atlantic Ocean."

— Nominating and voting transparency: Jon Landau's acknowledgement that the Hall does a good job of keeping the proceedings nontransparent and that "it all dies in the room" itself has to die. This is not national security. This is determining legacy for music of the Rock and Soul Era, a component of pop culture—and the acknowledgement of non-transparency is a tacit admission that the Hall is gaming the selections to reflect its conception of the legacy, the canon that is defining who is historically important. Making the balloting statistics public must be a standard practice. It is certainly a common-sense one—unless you're hiding something.

New Stewardship of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation as it stands now must go. If the Hall does expand to a "Smithsonian Institution" model, those administrative requirements will exceed the current capacity, and with the popular perception that the Foundation is running a rigged game, it is standard public relations strategy to make those top-down changes to restore confidence in the system.

Does It Matter?

But even if the fundamental fixes outlined above, or some other in-scope alternative, are implemented, does it even matter? When even those inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame bite the hand that feeds them by castigating the very institution that has enshrined them (which in any event may be a very rock and roll attitude), does the Hall hold any relevance? Particularly as the Hall begins to mirror how diffuse, diverse, expansive, and inclusive popular music has become.That is the issue I have been wrestling with for some time. When I first learned in the early 1990s that there was such an institution as the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, quite frankly, my first impression was: That seems pretty cheesy. Familiar with the Halls of Fame for the Big Four American sports, I thought of them as being "establishment," and like millions of people, I had the impression that rock and roll was anti-establishment, and wasn't a Hall of Fame for rock music an admission that it was now just part of the "establishment"?

Perceptions change as we grow older, runs the conventional wisdom, and mine certainly have. Part of that involved my continuing interest not just in music but, as someone with a corresponding interest in history and the social sciences, how that music reflects society overall.

For this website, I had written a series of "audits" of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, evaluations of the performers inducted from 1986 to 2013:

— Part 1 covers inductions from 1986 to 1990

— Part 2 covers inductions from 1991 to 1995

— Part 3 covers inductions from 1996 to 2000

— Part 4 covers inductions from 2001 to 2005

— Part 5 covers inductions from 2006 to 2010

— Part 6 covers inductions from 2011 to 2013

Overall, it was an enlightening experience, if only to challenge my biases, prejudices, and limitations. I began with an initial sorting of the inductees into three "buckets": Yes, Borderline Yes, and No. (A "Borderline Yes" simply indicates that there may be contention concerning inclusion and thus a case should be made to support that inclusion.)

As I began to investigate each case, I found myself moving specific inductees from one bucket to another—generally from a "No" to either of the "Yeses." Two examples are Leonard Cohen and Brenda Lee, whose bodies of work I was admittedly unfamiliar with—a clear case of "limitations"—until I actually began to listen to their output and research their careers. In the case of Guns 'N Roses, whom I'd not considered Hall-worthy because of a short career and limited output ("bias"), I realized that its impact and influence outweighed its relatively brief career. Meanwhile, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, whom with the exception of bassist Flea I'd never considered musically or technically proficient ("prejudice"), nevertheless had an impact and influence that exceeded their perceived shortcomings—and as we have been stressing all along, with no objective evaluation criteria that can be universally measured, what is the yardstick to measure that? There is none.

Nevertheless, my overall approach still entailed an expansive view of the music. To me, it seems perfectly logical to include Madonna, Bob Marley, and Miles Davis in the Hall even though none of them resemble the old white guy's conception of "rock and roll."

And yet I also held the perception of the "small hall," of needing to establish a baseline, or threshold, of "unquestionable musical excellence" that neither the Hall could define nor myself even in the five Defining Factors I have cited above. Thus, I found myself genuinely agonizing over whether I would include either LaVern Baker or Ruth Brown in the Hall—but because of my "small-hall" perception, I could not have both. In the end, I gave the thumbs-up to Baker, reasoning that she had the technically and aesthetically "better" voice, even though Baker was always reluctant to sing "rock and roll"—and even knowing that Atlantic Records, the supremely influential label for whom Brown recorded, was known as "the house that Ruth built."

Similarly, I gave the thumbs-up to Brenda Lee but not to Dusty Springfield, largely because she wasn't as popular in the United States as she had been in Britain, and because her critical and commercial success had waned by the 1970s—and, again, doing so even though I knew that in their Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock, Nick Logan and Bob Woffinden of New Musical Express claimed that Springfield "was the best female rock singer Britain ever produced." Granted, my edition of their book was published in 1977, so the "ever" part could be challenged now, but she had already established a legacy—and don't think I don't feel the daggers of foolishness and regret every time I hear Dusty unleash "Brand New Me" or "Mama's Little Girl."

The final irony is that, when I tabulated all the audits, I concluded that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame got it right about 75 percent of the time. That's a passing grade, a solid "C," perhaps not a gold star—but hardly terrible enough to label it a "Hall of Shame" or a "Hall of Lame." And as I've just suggested, that "grade" could go up as I would now include Ruth Brown, Dusty Springfield, and others such as Buddy Guy as being "valid" inductees.

Of course, that's just my perception of the Hall's inductees (at least up to 2013). Your mileage may vary. Everybody's mileage may vary because we are all shaped by our biases, prejudices, and limitations, and to repeat the mantra yet again: There is no standard definition of "rock and roll," there are no objective evaluation criteria that can be universally applied, and a constantly-evolving music means an ever-more expansive and inclusive Hall. And as I reflect on that exercise now, I believe that not only was the attempt to cast a wide net but yet maintain a "small hall" attitude a fool's errand, but it was as arbitrary as the efforts of the Hall itself.

But even if those fundamental issues are addressed in a fundamental manner as outlined above, we are likely to have a Hall of Fame that is so sprawling as to be meaningless. A "Smithsonian Institution" approach can mitigate some of that. Using the existing Smithsonian as an example, if all you care about is airplanes and space exploration, you go to the National Air and Space Museum and don't bother with the National Museum of Natural History, or any of the other affiliated institutions. Similarly, if you are a metal fan, you care about what happens at the Heavy Metal Hall of Fame and ignore others, such as the Singer-Songwriters Hall of Fame or Hip-Hop Hall of Fame. (All currently hypothetical Halls, of course.)

But can you accept that those other Halls of Fame are all part of the larger Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? If you can, then we have a Smithsonian Institution model in which we have an overarching concept of popular music since the 1950s, one in which you might not be interested in other forms and genres but you accept that they are all part of this larger, ever-expanding body.

If you cannot, then we have Balkanization, in which that popular music has splintered into component factions that are at best indifferent and at worst antithetical to each other. (And I will note only in passing another huge bias heretofore unmentioned: I have been speaking only about the "rock and roll" associated with the West, meaning Europe, English-speaking North America, and Australia and New Zealand. What to do about "rock and roll" in Africa, Asia, and Latin America? That would require a United Nations model!)

In either case, does it matter?

Since 2013, I have been posting my ballot assessment for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I did not post one for the 2017 ballot, partly because of outside issues, but largely because I found it harder to expend time and effort on what I was coming to realize was a meaningless exercise.

Not meaningless in the sense that I no longer considered whether any given artist should or should not be in the Hall; indeed, I had started the assessment, but then decided that it was meaningless because of the fundamental issues with the Hall that form the core of this article. In fact, I had written about that as the preamble to the ballot assessment, and I wound up scrapping the ballot assessment—which, as the ramifications of the fundamental issues became more salient to me, seemed like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic—and expanding the preamble into this article instead.

The question remains: Does it matter?

In the largest sense, yes, it does. As Courtney E. Smith noted, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, for better or for worse, has begun to establish a canon for the era around which it was founded. This canon, exemplified by the inductees in the Hall, shapes our perceptions of the music of the era and leads to the reactions of fans exemplified by innumerable examples of "the Hall of Fame sucks because Artist A [the artist I hate] is in but the Artist B [the artist I love] is not."

And with each succeeding year that makes new artists eligible for the Hall, fans indifferent to older acts start to become engaged—witness Jillian Mapes's Gen X colleague who now seemingly "has to care" because Nirvana was inducted—thus adding to that canon, no matter how skewed or slanted that canon may appear.

Music is an intensely emotional and intimate experience, one that stays with us throughout our lives, especially the music that moved us in our formative years of childhood through young adulthood. This is the wellspring for the depth of feeling people have when it comes to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the artists it inducts, or does not induct.

So, in that sense it matters as well: The Hall is an embodiment of that individual and collective experience, no matter how fundamentally flawed is that embodiment. We have examined why the Hall is fundamentally flawed, and what fundamental fixes could try to remedy those flaws. "Try" is the operative word as there may not be a fix for an entity, "rock and roll," that (one last time) has no standard definition, no objective evaluation criteria that can be universally applied, and that continues to evolve, making "rock and roll" ever more expansive and inclusive.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has its biases, prejudices, and limitations. So do we. And while we can suggest, even demand, fixes both major and minor to the Hall, we also need to make those fixes to ourselves.

Can you overcome your biases, prejudices, and limitations to accept that your definition of "rock and roll" in all likelihood does not match anyone else's? Can you use aesthetic reflection and aesthetic judgment to accept that artists you do not like, or that you think are not "rock and roll," may in fact be worthy enough to be added to the canon? Above all, can you accept that even if you can accept the last two conditions, that ultimately the endeavor of trying to define a canon through the Hall of Fame process, even with fundamental fixes applied, may indeed be a fool's errand because the scope is too broad and expansive?

If your answers are "yes," then we may have a "Smithsonian Institution" outcome, which is not a perfect solution but at least it recognizes the daunting gamut of the endeavor and tries to accommodate its enormous scope. But if your answers are "no," then we have "Balkanization," and what had been initially labeled "rock and roll" has splintered into the various factions that were created and developed following the Big Bang of Rock and Roll in the mid-1950s and exist separately with little to no connection to each other.

In the latter case, Snowden dies from the abdominal wound, to use our Catch-22 analogy, because no matter how well you bandage the less-serious leg wound, it won't address the more-serious wound left unattended; put more simply, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has run its course.

Yossarian bandages Snowden's leg wound--but it's the belly wound that will kill him. Similarly, the Rock Hall requires fundamental fixing--

Band-Aid solutions offered previously do not address the fundamental issues that can doom the Rock Hall to perpetual suckage.

But along with the fundamental fixes to address the fundamental issues of what is wrong with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame needs to come fundamental changes to ourselves, recognizing that the dizzying growth and scope of popular music in the last six decades has been enormous and will continue to be so, and thus the Hall of Fame has long outgrown what had been called "rock and roll" at its outset, recognizing that there is no definitive method to determine how an artist is a Hall of Fame-caliber artist, and recognizing that even with fundamental fixes, the Hall of Fame will continue to be very imperfect—and that your Hall may not be the same as mine.

A daunting task? Yes. But we can try, dammit, and maybe do so to these words of wisdom from Pink Floyd's "Have a Cigar":

"It's a helluva start, it could be made into a monster

If we all pull together as a team"

« Prev Next

Comments powered by CComment