Index

Today's Era

Movies reviewed in this section:

Chasing 3000 (2010): 2.0 WAR

42 (2013): 3.6 WAR

Million Dollar Arm (2014) 3.1 WAR

Mr. 3000 (2004): 2.0 WAR

Moneyball (2011): 4.6 WAR

61* (2001): 3.1 WAR

Sugar (2008): 4.5 WAR

Trouble with the Curve (2012): 3.2 WAR

What defines Today's Era? In baseball terms, it reflects the current environment of baseball with its advanced statistics and keen understanding that baseball is big business—not that the two are mutually exclusive.

In movie terms, all of these films, regardless of when they are set, were made in the 21st century and reflect the advancements of contemporary filmmaking, particularly, in one case, the use of special effects. That case involves one of the two films with a historical narrative, with both films recognizing landmark occurrences in the history of baseball. And while two of the films in this era attempt an ultimately inept take on baseball legacy, four of them take a considered view of the dynamics and realities of baseball today.

Starting with the historical narratives, both of which use iconic numbers for their titles, 42 (3.6 WAR) revisits Jackie Robinson's 1947 Major League debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The number 42 was of course Robinson's uniform number, which Major League Baseball retired universally in 2004, which also marked the first Jackie Robinson Day on April 15, the date of Robinson's first game with the Dodgers, with every player on that day wearing 42 as his uniform number in honor of Robinson.

The first recipient of the current Rookie of the Year Award (awarded to just one rookie from both the American and National Leagues until 1949), Robinson was a first-ballot Hall of Famer in 1962, joining Bob Feller. Curiously, Robinson garnered just 77.5 percent of the vote to ease over the threshold (Feller coasted in with 93.8 percent), although suspecting any residual racism might not be the case.

First, Robinson was already 28 when he became an MLB "rookie," with his earlier years spent not only playing Negro League baseball but serving in the US Army as he was drafted in 1942, following America's entry into World War Two; Robinson was (in)famously court-martialed in 1944 after refusing to sit in the back of a bus, but he was acquitted by a panel of all-white officers and was himself honorably discharged as a junior officer.

Then, because of his advanced age as a player, Robinson played for just ten years; thus, his counting numbers are light although his rate stats are outstanding for a middle infielder of his or any era: he batted .311 lifetime, with an on-base percentage of .409 and a slugging percentage of .474. Finally, on that 1962 ballot were 78 candidates who received votes (contemporary ballots average in the mid-30s), with a staggering 35 candidates subsequently elected to the Hall of Fame, with all but one (Al Lopez) inducted as a player—although Jim Bottomley, Jessie Haines, Travis Jackson, and Lloyd Waner, among several others, are pretty marginal inductees, but that's another story.

We've seen Jackie Robinson's story told before, first by the man himself in The Jackie Robinson Story and then in Soul of the Game, and what is notable about writer-director Brian Helgeland's homage to Robinson's historic season is that it not only captures the feel of the period, it plays like a middlebrow baseball flick of the period, an earnest if fuzzy biopic laced with familiar platitudes that rarely cut below the surface.

Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey (Harrison Ford) wants to integrate baseball as much for pragmatic reasons as for idealistic ones—the Negro Leagues contained many excellent players who could staff championship teams. These include the Kansas City Monarchs' Robinson (Chadwick Boseman), gifted with both playing skills and the temperament to withstand the racist vitriol sure to accompany his appearance, such as that aimed at him by Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman (Alan Tudyk) during a game, in the film's most tensely staged scene. With support from loyal wife Rachel (Nicole Beharie), Robinson faces resistance even from his own Dodgers teammates, but with Rickey's and erstwhile manager Leo Durocher's (Christopher Meloni) encouragement, he helps lead the team to the National League pennant.

It could get ugly: Alan Tudyk's portrayal of Philadelphia Phillies' manager Ben Chapman provides uncomfortable tension in the Jackie Robinson biopic 42.

Helgeland's serviceable if predictable script doesn't stray from cliché, with Mark Isham's overloaded score peppering the emotional cues with musical fungoes. In the titular role, Boseman, lacking presence and looking a bit too young, is solid but not as electrifying as his subject while Beharie is adorable decoration. Ford, however, seems engaged by his pivotal role while John C. McGinley affects a game Red Barber, the Dodgers' announcer, and Meloni sparkles in limited screen time.

And why is Meloni's screen time limited? In 1947, baseball commissioner Happy Chandler (Peter MacKenzie) suspended Durocher for his "known associations with gamblers" as baseball had another brush with that kind of notoriety, which seems ripe for its own movie: The colorful "Leo the Lip," whose famous (mangled) observation "nice guys finish last" has become a well-worn trope, was already made for the screen.

First, Durocher was married to actress Laraine Day for several years; then he guest-starred on several television shows including a legendary episode of the sitcom Mister Ed in which the titular talking horse hits a home run off Hall of Fame pitcher Sandy Koufax and slides into home plate to complete the play, an image not soon forgotten. And speaking of sitcoms, Max Gail, part of the ensemble cast on the acclaimed police sitcom Barney Miller, portrays Burt Shotton, who took over the Dodgers' managerial duties during Durocher's 1947 suspension.

Other notable aspects about 42 are, thanks to computer-generated images, the digital recreations of bygone ballparks such as Brooklyn's Ebbets Field, Pittsburgh's Forbes Field, and Manhattan's Polo Grounds (home to the Dodgers' hated rivals the Giants), helping to reinforce Helgeland's atmosphere of a period baseball movie made in the period it is depicting. Still, as an updated Jackie Robinson Story, 42 hits safely but it's hardly a home run no matter which ballpark, real or virtual, it's set in.

Harrison Ford (as Branch Rickey, left) and Chadwick Boseman (as Jackie Robinson) are real but Brooklyn's Ebbets Field is CGI animation in 42.

Also awash in nostalgia is noted New York Yankees fan Billy Crystal, whose 61* (3.1 WAR) is his praise-song to his beloved Bronx Bombers' historic 1961 season, profiling the travails of Yankees' sluggers Mickey Mantle (Thomas Jane) and Roger Maris (Barry Pepper) as both assault Babe Ruth's then-record of 60 home runs hit in a single season. Long on detail and sentiment but short on distinction, director Crystal, managing Hank Steinberg's workmanlike script, displays the savvy of the informed, engaged fan, but that fandom also pervades his soft-focus portrayals of the "M&M Boys" with their warts and all but still on their pedestals.

In 1961, which saw the American League expand its season to 162 games, Ruth's record was still revered, and even if another Yankee should break it, fans wanted the superstar Mantle and not the journeyman Maris to be the one. The pressure mounts on both as each slugs his way to contention, but when Mantle becomes injured and Maris pulls ahead, the stress takes its toll on the taciturn Midwesterner, especially when baseball's Commissioner Ford Frick (Donald Moffat) decrees that the record must be broken within the 154-game span of Ruth's era. Occupying the film's center, Jane and Pepper, both of whom resemble their respective stars, provide convincing surface portrayals without digging too deeply beneath the dirt.

Thomas Jane (left) as Mickey Mantle and Barry Pepper as Roger Maris in 61*.

As Crystal frames Maris as the sympathetic one, Jane works harder to make his Mantle appealing, although Crystal can't resist revisiting sports-movie cliché, eagerly abetted by Marc Shaiman's overbearing musical cues, as Maris finally finds acceptance. Supporting Jane and Pepper are Jennifer Crystal Foley (Billy Crystal's daughter) as Maris's wife Pat, Peter Jacobsen and Richard Masur as a shrewd sports-writing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (echoing John Sayles and Studs Terkel in Eight Men Out), Christopher McDonald as Yankees broadcaster Mel Allen, Bruce McGill as Yankees manager Ralph Houk, and Anthony Michael Hall as Mantle's pal, pitcher Whitey Ford. Solid but predictably rendered, 61* won't set any records, although you don't have to put an asterisk next to it, either.

Speaking of asterisks, none of which were ever applied to Maris's record or any other record—although the steroids-users-are-cheaters crowd are dying to apply them even now—Maris did play in 161 games in 1961 while Ruth played in 151 games in 1927. However, Maris's 698 plate appearances are only seven more than Ruth's 691 even if Maris did play in ten more games. His 61st home run did come in his final game of the season, in his 696th plate appearance, with a solo shot off Tracy Stallard of the Boston Red Sox; it was the only run scored by either team.

Baseball history, or more accurately its legacy, remains the focus of our next two movies, one purely fiction and one a fictionalized narrative keyed to actual baseball history. That legacy, another statistical milestone, is the accomplishment of reaching 3000 hits, an achievement that only thirty-two hitters in Major League history have attained. In 1972, Roberto Clemente became the eleventh hitter to join that elite circle when he doubled in his last regular-season at-bat. Three months later, the Latinx superstar died in a plane crash while on a mercy mission to aid victims of a massive earthquake that rocked Nicaragua.

Chasing 3000 (2.0 WAR) uses Clemente's quest as the impetus for two teenage brothers to return to Pittsburgh to see him attain that hallowed milestone in person using a time-honored device, the road trip, as the vehicle that reduces the iconic Hall of Famer, seen only in archival footage, to a MacGuffin in service to hackneyed family melodrama. With Cris D'Annunzio, Bill Mikita conceived the story based on his brother Steve, a wheelchair-bound lawyer with muscular dystrophy, rendered here in teenage form as Mickey (Trevor Morgan) and Roger (Rory Culkin), forced by their single mom Marilyn (Lauren Holly) to move from Pittsburgh to Southern California in the hope of alleviating Roger's disease.

Resentful, ill at ease, missing their grandfather "Poppy" (Seymour Cassel), Mickey decides to "borrow" mom's car for a trip back home, ostensibly to see Clemente reach 3000 hits, with Roger tagging along as they leave a trail of contrivances in their impetuous wake strewn across America. First, they have to stop at an emergency room because Roger forgot to bring his meds. Then, when Marilyn discovers her car is gone along with her two boys, she alerts the police, which forces the boys to abandon the car and hop a freight train, where they meet Kelly (Tania Raymonde), a teenage drifter who gets them not to St. Louis, where they can catch another train to Pittsburgh, but somewhere in the wilds of Alabama as Clemente closes in on his milestone.

Hoping to catch Roberto Clemente make history in 1972, Roger (Rory Culkin, left) and Mickey (Trevor Morgan) hop a freight train in Chasing 3000.

Baseball may be routine and predictable, but we watch to see when it isn't, an expectation Chasing 3000, generically directed by Gregory Lanesey, pursues in vain as every twist is telegraphed, every complication is fabricated, every emotion, underlined by Lawrence Shragge's cloying score, is calculated, with no symbol too obvious. (Mickey and Roger? You mean Mantle and Maris?) As the brawn, Morgan is unremarkable, but Culkin, as the brains and the object of pity, flashes some depth while Ray Liotta plays the adult Mickey with two kids of his own in the narrative frame as veteran supporters Keith David (you know his voice from many baseball documentaries) and M. Emmett Walsh carry water in a transparent tale that sacrifices Clemente to advance an ill-conceived conceit.

With exactly 3000 hits, Roberto Clemente is Mr. 3000 and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973 as the Hall waived the five-year eligibility requirement on account of his 1972 death while still an active player. On the other hand, Stan Ross (Bernie Mac), the fictional Mr. 3000 (2.0 WAR), finds it a challenge to be elected to the Hall of Fame even when he too reaches that hallowed milestone.

Talented but arrogant and surly to the fans and the media, Barry Bonds—sorry, Stan Ross—star player for the Milwaukee Brewers, notches his 3000th hit, but following a snit with reporters in the locker room after the game, Stan abruptly announces his retirement, noting that he's headed for the Hall of Fame anyway. (Can you say "hubris"?) However, Stan quits right as the Brewers are in a tight pennant race, making him even more unpopular with the fans—and now with his teammates and his manager, Gus Panas (Paul Sorvino).

No matter, because Stan uses his "Mr. 3000" moniker as the marketing label for his string of business ventures as he awaits the call to Cooperstown. But he doesn't get that call during his first few years of eligibility, and when statisticians review his game logs, they discover that he had been credited with three more hits than he actually collected over his career. With both his Hall of Fame credibility and his marketing slogan accuracy on the line, Stan persuades the Brewers to let him make a comeback at age 47 so he can try to get back those three little hits.

Get right back to where I started from: Stan Ross (Bernie Mac, batting) has to chase 3000 hits all over again for the dubious premise of Mr. 3000.

This premise, cooked up by Eric Champnella and Keith Mitchell with Howard Michael Gould helping with the screenplay, is not only flimsy and dubious, but baseball fans know that it's asinine—in a sample size of 3000 hits, three hits are statistical noise. Stan is still the same caliber of player at 2997 hits as he is at 3000 hits. Moreover, if Stan was striking out with the Hall of Fame at 3000 hits before this clerical error was discovered, how does getting back to 3000 hits, where he started from, improve his chances now? Or is this all a cost-cutting measure so he doesn't have to rebrand his businesses? (Speaking of branding, just how successful could the "Mr. 3000" marketing label be if Stan "Mr. 3000" Ross himself is not exactly Mr. Popularity?)

All right, that shaky premise might have a kernel of credibility. The late, great Detroit Tigers right fielder Al Kaline might be the poster boy for the just-missed-the-milestone crowd. In his career, he batted .297 (three points shy of .300) with 498 doubles (two shy of 500) and 399 home runs (one shy of 400). But he did collect 3000 hits, 3007, to be precise. (Returning to the fictitious Stan Ross: Assuming he got back to 3000 hits, would he quit again? Or would he try to move past Clemente on the all-time list?)

However, Kaline was concerned that by not getting to that milestone, he might not be considered worthy of the Hall of Fame. He finished the 1973 season, in his age-38 year, with 2861 hits, having banged out 79 hits in just 91 games and 347 plate appearances as, banged up by age and injuries, he was nearing the end of his career. But determined to reach 3000, he returned in 1974 and, appearing exclusively as the Tigers' designated hitter, introduced into the American League the previous season, in 144 games and 630 plate appearances, he knocked out 146 hits to push himself past the 3000-hit threshold. Then he retired.

Al Kaline was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1980, his first year of eligibility, with 88.3 percent of the vote. Also elected that year was Duke Snider, with 86.5 percent of the vote; it was Snider's eleventh year on the ballot. That ballot had 61 candidates, ten of whom were voted into Cooperstown on future ballots.

Was it necessary for Al Kaline to have reached 3000 hits in order to be voted into the Hall? Certainly, he thought so. As we've been reminded by articles and news reports of his recent passing at age 85 on April 6, Kaline was that rarity among celebrities: a humble, unassuming superstar who downplayed his own greatness. True, playing his entire career in Detroit, he didn't get as much exposure as players in larger media markets although during his 22-year career, he was voted to the All-Star squad in 15 of those years, making his name notable in any case.

Perhaps he would not have been a first-ballot Hall of Famer had he retired after the 1973 season, but I find it highly unlikely that he wouldn't have been voted in at some point during his eligibility—and sooner rather than later—even knowing that voters might withhold their approval for a myriad of reasons. For instance, I still find it hard to believe that it took Rogers Hornsby five tries to get elected to Cooperstown. Yes, he was a driven son of a bitch who was probably more unpopular than our fictitious Stan Ross, but the baseball writers of Hornsby's time couldn't have been that churlish. Could they?

Speaking of Stan Ross, no, the premise of Mr. 3000 doesn't have a lot of integrity to it, but that is not the point of this sports comedy. Stan must learn the lessons of humility and generosity while serving as the example for the Brewers' new Stan Ross, slugging center fielder T-Rex Pennebaker (Brian J. White), not to be an arrogant jerk as Stan tries to rekindle his relationship with reporter Mo Simmons (Angela Bassett), all of which has the predictability of a routine grounder to short.

Stan Ross (Bernie Mac, left) also tries to chase reporter Mo Simmons (Angela Bassett) in Mr. 3000. Don't strike out, Stan.

Fortunately, Bernie Mac takes the role seriously enough to sustain interest as director Charles Stone III doesn't dwell too long on the clichés—even if this story does exhume the old hidden ball trick—keeping the pace lively as it checks off the plot points on its lineup card. Supporting players Chris Noth and Michael Rispoli buttress the tale, with Sorvino supplying the amusing gimmick before Stan makes the ultimate sacrifice (bunt). Nevertheless, Mr. 3000 is hardly bound for Cooperstown.

Although the movies in Today's Era lack strength in conveying baseball's history and legacy, movies that examine the conditions of contemporary baseball make a strong showing, barring a slip or two. One of the constant challenges of the sport is finding talent, which has become an international quest as the sport has spread across the globe.

And although India has not yet proved to be a fertile source, that cricket-crazy country did inspire sports agent J.B. Bernstein to travel there in 2008 to create a reality-television show, Million Dollar Arm, to search for live arms to satisfy that eternal baseball plaint: you can never have enough quality pitching. Million Dollar Arm (3.1 WAR) depicts Bernstein's (Jon Hamm) true-life tale about how he and his business partner Ash Vasudevan (Aasif Mandvi), gambling everything they had on the venture, went halfway around the world to find a pair of pitching prospects.

But since this is a Disney biopic, don't be surprised that Tom McCarthy's sharp, tidy script assiduously ticks off the dramatic boxes on the way to its feel-good conclusion. After losing their shot at a business-saving client, J.B.—inspired by watching Indian cricket bowlers—and Ash convince an investor (Tzi Ma) they can land a couple of prospects in India, then line up pitching coach Tom House (Bill Paxton) to train the raw recruits.

After obligatory culture-shock routines in India (think: exotic food and differences in how to conduct business), J.B. returns to the US with Dinesh Kumar Patel (Madhur Mittal) and southpaw Rinku Singh (Suraj Sharma) in tow. Neither of them even likes cricket, let alone plays it, but, hey, they can throw a baseball fairly hard. Back in Los Angeles, however, they flounder under J.B.'s inattention until Brenda Fenwick (Lake Bell), a physician intern renting the cottage in J.B.'s back yard, intervenes, leading to the Big Tryout before MLB scouts.

Bonding while enduring culture shock in Los Angeles (L-R): Suraj Sharma, Madhur Mittal, Pitobesh Tripathy, and Jon Hamm all hoping that Million Dollar Arm will pay off for them.

Director Craig Gillespie's slick pacing keeps the wheel of karma, or at least the wheel of crisis resolution, spinning smoothly as J.B. confronts—or is confronted by—all the obstacles to his success, especially the realization that his success ultimately resides in the success of his charges, two village boys suddenly transplanted to Southern California. (Remember, this is a Disney production.)

Hamm is a solid starting player who gets winking support from Darshan Jariwala, Pitobesh Tripathy, and especially Alan Arkin's cranky-old-man persona, this time as a grizzled scout who's seen it all—or, more accurately, he's heard it all—and Million Dollar Arm would have benefited from more Arkin. Instead, we get Hamm's shaky chemistry with a much-too-glib Bell; not surprisingly, it fizzles despite the fact that she tears up at the end of watching The Pride of the Yankees with him. (Reminder: Disney.) Fortunately, A.R. Rahman's Indo-eclectic score sizzles like a high-and-tight fastball, although it loses velocity once the action moves from India to Los Angeles, as Million Dollar Arm delivers pleasant, predictable lessons.

He's heard it all before: Alan Arkin's grizzled scout Ray knows the sound of a live pitch with his eyes closed, but he could have kept them open longer for Million Dollar Arm.

Culture shock plays a central role in Sugar (4.5 WAR), although this time it's not an exotic novelty but a central reality as this incisive look at both the minor leagues and the struggle to break into the Majors from the perspective of countless players from Latin America makes for one the best baseball movies of this era—or any other era, for that matter. In fact, Sugar transcends mere baseball to become one of the finest contemporary immigrant stories extant.

Miguel "Sugar" Santos (Algenis Perez Soto) is a young Dominican Republic pitching phenom who enters the farm system of the fictitious Kansas City Knights; called to spring training in Arizona, he earns a berth with the Knights' single-A team in Iowa. While living with a host family, Sugar succeeds in spite of the cultural and language differences, but when an injury sidelines him, he struggles to overcome not only the physical ailment but, more seriously, the psychological obstacles faced by those under constant pressure to avoid failure and be sent packing—which is only exacerbated by being a stranger in a strange land.

With his sweet delivery, Miguel "Sugar" Santos (Algenis Perez Soto) hopes to make it to the Major Leagues in Sugar--if he can weather the culture shock in the United States.

Leading a cast of unknowns, Soto proves credible as an actor and a ballplayer, providing a clear focal point into both the baseball and the immigrant experience. Writer-directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck foster this not only with extraordinary detail, but with a documentary filming style that avoids sentimentality as it stresses realism.

The plush baseball academies in the Dominican Republic provide a harsh contrast to Sugar's (Algenis Perez Soto, right) impoverished hometown, which he is determined to escape in Sugar.

First up is the dramatic contrast between the plush Dominican baseball academy, funded by the Major League team in the United States, and Sugar's poverty-stricken home town. Then comes Sugar's trek to the US, where he bunks with host families, learns to order correctly—and economically—at coffee shops, and adjusts to the various ballparks, all familiar territory for countless domestic minor leaguers, but terra incognita for Sugar and his fellow Latinx players all weathering the cultural and language barriers that compound the challenges of just trying to stay in baseball and move up the ladder to the parent team.

Boden and Fleck's documentary realism does mean that no strong personalities emerge, not even Sugar's; this flattens the narrative and makes no one outside Sugar memorable, although his change-of-heart motives in the film's final third are murky, perhaps deliberately so. Nevertheless, Sugar is one of the most compelling baseball movies you'll ever see, and given Dominicans' current dominance in the game, one that's long overdue.

Did I order the right dish? Sugar Santos (Algenis Perez Soto, foreground) navigating everyday life in the United States in Sugar.

Moving from the now-global search for baseball talent to evaluating baseball performance are two movies that play as natural contrasts to one another, with one epitomizing the sabermetric revolution and the other exemplifying the traditionalist approach. And as the traditional movie was released after the saber movie, it is hard not to think that it was a deliberate rejoinder to all those newfangled statistics—don't you know that you can't play baseball from a spreadsheet?

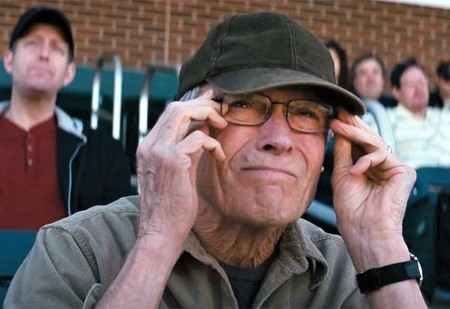

And who better to play that crotchety old coot, who knows his instincts and don't need no fancy numbers, than Clint Eastwood? In Trouble with the Curve (3.2 WAR), Eastwood is Gus Lobel, a grizzled scout for the Atlanta Braves who would be staring retirement in the face if only his eyesight was better. Disdaining the modern statistical analysis—there's that damned spreadsheet again—favored by ambitious Braves front-office executive Philip Sanderson (Matthew Lillard), Gus relies on his instincts and lifetime of experience—and, as it turns out, he's like Alan Arkin in Million Dollar Arm: he knows 'em when he hears 'em—as he heads to North Carolina to see high school phenom Bo Gentry (Joe Massingill).

Grizzled baseball scout Gus Lobel (Clint Eastwood) can't always trust what he's seeing--or not seeing--while trying to determine who has Trouble with the Curve.

Gentry is a possible top draft pick also being scouted by the Boston Red Sox, whose scout Johnny Flanagan (Justin Timberlake), also investigating Gentry, had been one of Gus's finds when he was a player. Concerned that the Braves will send Gus to the showers if he blows the call on Gentry, Gus's boss and friend Pete Klein (John Goodman) persuades Gus's daughter Mickey (Amy Adams) to accompany Gus. Mickey, pushing to become a partner at her law firm, is reluctant to go, but of course she does, triggering flirtations from Flanagan and flare-ups with her father on the way to the finish.

Like father, like daughter? Lawyer Mickey Lobel (Amy Adams, left), Gus's (Clint Eastwood) daughter, flashes baseball instincts like his in Trouble with the Curve.

Newcomer Randy Brown's unexceptional script (which became subjected to a subsequent plagiarism lawsuit) flashes its baseball trivia along with cardboard supporting characters played by Massingill, Lillard, and Robert Patrick as the Braves' general manager, while the feel-good conclusion is just too pat. But director Robert Lorenz doesn't waste time between pitches, keeping the story on pace before you can spot the derivations.

Eastwood is reliable as the crotchety old coot, and Timberlake is serviceable, but it is Adams who is the workhorse here, pushing her too-perfect ambitious lawyer and alternately resentful and hopeful daughter past the clichés while sounding sexy when she breaks down for Timberlake the late-1965 trade that sent Hall of Fame outfielder Frank Robinson, whom the Cincinnati Reds considered past his prime, to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher Milt Pappas. (In his first year with the Orioles, Robinson won the batting Triple Crown.) Somewhat hackneyed and hardly original, Trouble with the Curve serves up predictable pleasures.

Throwing her a curve: Mickey Lobel (Amy Adams, left) tangles with dad's rival scout Johnny Flanagan (Justin Timberlake) just to make more Trouble with the Curve.

When journalist Michael Lewis published Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game in 2003, he shone the spotlight onto the stealth revolution that was percolating within the lower reaches of Major League Baseball—literally the lower reaches, as in the teams that didn't have the exorbitant payrolls of teams that could buy themselves pennants and championships with high-priced superstar players.

Yet somehow the Oakland Athletics, at the time of Lewis's book next-to-last in terms of payroll spend, managed to make it into the postseason even after the loss of three marquee players after the 2001 season: center fielder Johnny Damon, first baseman Jason Giambi, and relief pitcher Jason Isringhausen. By now, we all know the story of A's general manager Billy Beane and the various analysts, especially Paul DePodesta, he hired to help him find the overlooked and underappreciated players, from raw rookies to wizened veterans to in-between misfits, who couldn't replicate what the departed players provided but could supply part of that—all while being affordable to a franchise that still clipped coupons to stretch its budget.

Along the way, Lewis shed light on Bill James, the Grand Old Man of sabermetrics, who, while working at a night watchman at a Hormel packing plant in the Midwest, worked out re-evaluations of baseball talent that even reassessed established players as being overrated or underrated. James's insights slowly spread until Beane, himself a potential phenom who couldn't catch on in the Majors, saw them as a pathway to keep the A's a winning team even among the big-money franchises such as the Boston Red Sox, who got Damon, the New York Yankees, who got Giambi, and the St. Louis Cardinals, who got Isringhausen.

Thus, we learn how Beane and DePodesta and the A's managed to "recreate the aggregate" of the departed players with players such as Giambi's own brother Jeremy, who chased balls in left field "like a postman trying to escape a mad dog," but who could wear out a pitcher to cadge a walk off him. Or Scott Hatteberg, a backup catcher whose operation to repair a ruptured nerve in his throwing arm fixed the nerve but left him unable to throw, who never played first base in the Majors but who managed to do so almost by dint of A's infield coach Ron Washington's constant reminder that he was a "pickin' machine," picking out throws in the dirt. On the other side of the baseball, relief pitcher Chad Bradford, who didn't throw hard or fast, managed to not walk hitters nor give up home runs and even strike out a batter every inning or so—the Golden Mean of the Three True Outcomes for a pitcher—because his submarine delivery not only confused hitters, it induced a lot of ground balls, which tend not to disappear over the fence for a home run.

Condensing Lewis's milestone work into a movie version meant simplifying the storyline down to basics, which screenwriters Aaron Sorkin and Steven Zaillian manage as they fashion the narrative into a familiar pattern that might offend purists but works to broaden the appeal of Moneyball (4.6 WAR) and its principles of sabermetrics to a wider audience. (Two friends of mine, both women and neither a baseball fan, not only thought Moneyball was a good film—they both enjoyed it.)

I ain't buying what you're selling. Billy Beane (Brad Pitt, smiling) doesn't seem to be convincing his players that his Moneyball approach will actually win them games.

Looking to rebuild after the 2001 departure of his marquee players, Beane (Brad Pitt) encounters Paul Brand (Jonah Hill as a composite of several analysts including DePodesta, who did not want to be named in the movie), a budding analyst toiling in the Cleveland Indians' front office whose unorthodox ideas about assessing player value through statistical analysis intrigue Beane, desperate to keep the A's competitive while on a tight budget. Beane lures Brand to Oakland, where they begin to acquire overlooked and underrated players to "replace in aggregate" what the A's had lost.

Who says you can't play baseball through a spreadsheet? Paul Brand (Jonah Hill) helps the budget-challenged Oakland Athletics find undervalued players in Moneyball.

Of course, this runs counter to the conventional wisdom of the traditional scouts (paging Gus Lobel from Trouble with the Curve!) and the on-field managerial expertise of Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman), and when the A's get off to a rocky start, they and the baseball establishment feel vindicated. But then the contributions of the motley squad that includes Scott Hatteberg (Chris Pratt), David Justice (Stephen Bishop), and Chad Bradford (Casey Bond) begins to cohere, and the A's not only find themselves in contention, they reel off a string of nineteen consecutive wins to tie the American League record, leading to the twentieth game that seems like a lock to break the record—but as Yogi Berra once said, it ain't over 'til it's over.

True, Moneyball does feature the stereotypical "big game" at its climax, and to broaden the appeal, director Bennett Miller backlights Beane's personality, which includes his relationship with Casey (Kerris Dorsey), his young daughter with ex-wife Sharon (Robin Wright), with Casey urging dad, who, famously and idiosyncratically, never watches his team's games, to see if the A's can make history. (It is entirely possible that my two female friends who liked Moneyball might have been lured into the theater because Brad Pitt was portraying Beane.)

Yes, it's the Big Hit in the Big Game, but . . . Scott "Pickin' Machine" Hatteberg (Chris Pratt) launches one to help the A's make baseball history (really) as depicted in Moneyball.

No matter, because Moneyball also features contemporary realism both on and off the field. Miller manages to stage front-office scenes with grit and substance even with obligatory shots of meaningful peering into computer screens, while the playing action flashes genuine credibility: Both Bishop and Bond played minor-league ball as did Derrin Ebert, who portrays relief pitcher Mike Magnante, and who even had two fleeting cups of coffee with the Atlanta Braves in 1999 (he did pick up a save), and—ringer alert—Royce Clayton, who collected 1904 hits and 231 stolen bases during his 17-year career as a Major League shortstop, and who portrays another shortstop, Miguel Tejada.

Including Tejada, albeit briefly, does belie the impression of the 2002 Oakland A's as the Bad News Sabermetric Bears scraping together an MLB-worthy team that Moneyball projects. In 2002, Tejada batted .308 with 204 hits, 34 home runs, 108 runs scored, and 131 runs batted in—all team bests—as he was named the American League Most Valuable Player; furthermore, with just 38 walks in 715 plate appearances, "Miggy" was hardly the kind of undervalued on-base secret weapon Beane and Brand (i.e., DePodesta) had in mind.

Moreover, the 2002 A's also featured a starting rotation that included three pitchers, right-hander Tim Hudson and southpaws Mark Mulder and Barry Zito, who were beginning to be compared to the Atlanta Braves' future Hall of Famers Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux, and John Smoltz. (Hudson was actually traded after the 2004 season to Atlanta, where he spent the majority of his 17-year career.) In fact, in 2002, Zito posted an AL-leading 23 wins against just five losses and a 2.75 ERA to garner the AL Cy Young Award. In other words, the A's had some more traditional talent to rely upon.

However, sticking too closely to the literal facts makes for a good documentary but not a good dramatic film, which is why Hoffman's Art Howe becomes the designated villain in Moneyball, consigned to the periphery to grouse about the abuse of old-school baseball as the keyboard warriors take over the team. That's showbiz for you. In any case, Pitt is the convincing backbone to Moneyball, Brent Jennings gets a humorous turn as Beane's infield coach Ron "Pickin' Machine" Washington (movie trailer pull-quote as Beane is trying to convince Hatteberg to play first base: Pitt: "It's not that hard, Scott. Tell him, Wash." Jennings: "It's incredibly hard."), although Hill is ultimately hitless even if he did snag a Best Supporting Actor nomination. But in the last analysis, Moneyball never fails to get on base, and that's the bottom line.

It can get lonely in the dugout sometimes. A's manager Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman) having to play the cards Billy Beane and Paul Brand have dealt him to play in Moneyball.

Comments powered by CComment