Index

The Modern Era

Movies reviewed in this section:

The Bad News Bears (1976): 4.8 WAR

Bull Durham (1988): 5.0 WAR

Eight Men Out (1988): 5.0 WAR

Field of Dreams (1989): 2.0 WAR

A League of Their Own (1992): 4.5 WAR

Major League (1989): 4.4 WAR

Mr. Baseball (1992): 3.2 WAR

The Natural (1984): 3.2 WAR

Soul of the Game (1996): 3.3 WAR

What defines the Modern Era? In baseball terms, this is the era of both league expansion and tiered postseason play, although only one of these movies is actually set in Major League Baseball during this era.

In fact, in movie terms, all the other films are split between gauzy nostalgia for earlier eras—although at least one of them lifts the gauze for a harder examination—and, intriguingly, perspectives on baseball other than at the Major League level—and not just in the United States—with one movie managing to split the difference.

The nostalgia movies harken back to the sentimentality of earlier baseball movies—one of them egregiously so—while the contemporary movies have a sardonicism that can be both refreshing and hilarious. But all of them have strong production values while flashing fairly credible baseball action—even when the baseball is supposed to be deliberately bad.

Looking at the movies in this era, though, it is tough not to say that this, at least from a cinematic perspective, is the real "Golden Era" for baseball movies, with a number of these titles among the most popular and well-regarded of any baseball movies.

A prime example of this is one movie in which the baseball is supposed to be deliberately bad, but whose impact is hilariously brilliant. I speak of course about The Bad News Bears (4.8 WAR), which taught us that life's bittersweet lessons can be found anywhere, and for The Bad News Bears they're learned on the Little League baseball diamond: It's not whether you win or lose but, rather, how you hold a grudge.

Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau) contemplating tough decisions as the coach of The Bad News Bears.

Bill Lancaster's ribald script skewers mid-1970s American middle-class suburbia with a refreshing lack of sentimentality even as this uproarious satire slyly celebrates that hoariest of sports-film tropes, the Cinderella story, with a rainbow coalition of misfits and losers led by a most unlikely—and reluctant—inspiration. Once a minor-league pitching prospect, Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau) now cleans pools to support his drinking habit until he's paid to coach the Bears, which, thanks to a class-action suit, were created within an ultra-competitive Little League somewhere within the ocean of suburbs in Southern California.

The motley squad includes corpulent catcher Engelberg (Gary Lee Cavagnaro), asthmatic benchwarmer Ogilvy (Alfred Lutter), and pugnacious shortstop Tanner (Chris Barnes), and when they get creamed in the season opener by the Yankees, coached by taskmaster Roy Turner (Vic Morrow), Buttermaker must seeks ringers. One of those is pitcher Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O'Neal), the fireballing daughter of an ex-girlfriend, while the other, Kelly Leak (Jackie Earle Haley), a delinquent who terrorizes the ball fields on his Harley-Davidson dirt bike, just happens to be a slugging sensation, but the Bears' unlikely but inevitable climb toward the championship holds unforeseen challenges.

Keeping your ace focused on the game: Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O'Neal, left) gets pitching pointers from Buttermaker (Matthau).

Director Michael Ritchie's sharp pacing and perceptive framing hits the strike zone consistently as Matthau's Buttermaker sets the acerbic tone, particularly his prickly, intriguing relationship with O'Neal's Amanda, with Jerry Fielding's spare but effective score, adapted from Bizet's Carmen, accenting memorably. Moreover, the kids display believable dimension without affect, with charismatic juvenile hellion Haley an especial highlight, although Barnes and particularly Lutter, who made an auspicious debut opposite Ellen Burstyn and Jodie Foster in 1974's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (which inspired the sitcom Alice), give him a run for his money. And who can forget bespectacled Stein (David Pollock), willing to take one for the team? All right, maybe not so willing.

Meanwhile, Morrow, tasked as the villain, soldiers on dutifully as the dad you love to hate, with Brandon Cruz, playing his son Joey, executing some classic 1970s nose-thumbing at authority (as well as at his own teammates) as The Bad News Bears cheekily defies convention. And how can you not love a team sponsored by . . . Chico's Bail Bonds? "Let Freedom Ring." (The Bad News Bears spawned two sequels and a remake, which if anything demonstrates how milkable the original remains.)

The Bears confer with their coach in The Bad News Bears. How can you not love a Little League team sponsored by . . . Chico's Bail Bonds?

But glorious ineptitude on the diamond is hardly restricted to Little League—it can even afflict the Major League (4.4 WAR), or at least the Cleveland Indians. At the time that writer-director David Ward made this enduring comedy, the Indians were a dilapidated franchise that had not won an American League

Pennant since 1954 (losing the World Series that year to the then-New York Giants, a Series most notable for "the Catch," Willie Mays's immortal defensive play in deep—I mean deep—center field in Game One), and they had not won a World Series since 1948; in fact, the Indians are still waiting to win a World Series despite three trips to the world championship since the movie was released, with their last two World Series appearances, particularly in 2016, among the most dramatic Series in baseball history.

Coming on like an unholy cross between The Bad News Bears and Airplane!, Major League shamelessly, gleefully expropriates the hoariest clichés from both baseball movies and actual baseball—the grizzled veterans, the hungry rookies, the heartless front office, and of course the Big Game—with utter predictability. And why not? Baseball is routine, repetitive, and predictable. Until it's not. Major League's wild thing is Ward's sleeper script that tips its pitches—until it doesn't—as it tosses out gags without belaboring them, producing belly laughs while slyly instilling a little sentiment.

Trophy-widow owner Rachel Phelps (Margaret Whitton) savors the downfall of the Cleveland Indians in Major League. Or is that premature?

Trophy widow Rachel Phelps (Margaret Whitton) is determined to sink the Cleveland Indians, which she now owns. Why? So she can move the team to greener pastures in Miami. That's why she restocks the already-moribund franchise with losers and misfits—career minor-league manager Lou Brown (James Gammon), broken-down catcher Jake Taylor (Tom Berenger), showboating walk-on Willie Mays Hayes (Wesley Snipes), and fireballing felon Rick Vaughn (Charlie Sheen), whose optical challenges yield his nickname "Wild Thing"—to join past-his-prime third baseman Roger Dorn (Corbin Bernsen), Voodoo-worshipping (and curveball-susceptible) slugger Pedro Serrano (Dennis Haysbert), and Holy Rolling, over-the-hill junkballer Eddie Harris (Chelcie Ross) for the final curtain.

Time to tame the Wild Thing (L-R): Tom Berenger ("Jake Taylor"), Charlie Sheen ("Rick Vaughn"), and James Gammon ("Lou Brown") confer.

Yet as the season progresses, Cleveland begins to rise from the dead, but can Phelps's sometimes-hilarious attempts at sabotage, such as cutting expenses for luxuries and amenities alike, ultimately tame the Tribe? One Airplane!-like gag has the team being shown an "alternate route" through the airport to board their charter flight, only to be led to a derelict Douglas DC-3—a propeller-driven airliner introduced into service way back in 1936—looking like a refugee from Casablanca.

Deluxe accommodations for the Cleveland Indians in Major League include this vintage Douglas DC-3, seemingly on the lam from some earlier movie, say Casablanca.

Top-billed Berenger gets dimension with his subplot to rekindle his relationship with swimmer-turned-librarian Lynn Weslin (Rene Russo), already engaged to a lawyer who is part of the downtown-chic crowd; upon learning that Jake plays for the Indians, one of them exclaims, "Here in Cleveland? I didn't know they still had a team!" Nevertheless, Major League is mostly a boys-only clubhouse, led by gravel-voiced anchor Gammon, with team announcer Harry Doyle (a riotous Bob Uecker) supplying sardonic narration that's just a bit outside the usual patter right up to the final play. (An alternate ending features a twist that rescues Phelps but smacks of too much contrivance.) James Newton Howard's bush-league score is synthetic pap, but using "Burn On," singer-songwriter Randy Newman's droll recounting of Cleveland's 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, over Major League's opening credits demonstrates smart pitch selection.

Still, the Indians wouldn't mind signing New York Yankees first baseman Jack Elliot (Tom Selleck), but the fictitious slugger winds up Japan playing for Nagoya's not-fictitious Chunichi Dragons in Mr. Baseball (3.2 WAR), and you already know that this American is going to experience Japanese culture shock both on and off the Nippon Professional Baseball field.

A hole in his swing you can drive a shuuto pitch through: Jack Elliot (Tom Selleck) navigates the finer points of Nippon Professional Baseball as Mr. Baseball in Mr. Baseball.

This workmanlike sports comedy endured a scripting saga, passing through a series of hands to satisfy both Selleck and Japanese sensibilities; what emerges is a heavily-massaged narrative as predictable as a lazy fly ball to straightaway center field, which still makes fans rooting for the team in the field happy, anyway. Jack certainly isn't happy with the deal as he feuds with his interpreter Yoji (Toshi Shioya), who has to tap-dance Jack's surly observations, and with his manager Uchiyama (Ken Takakura), whose bluster belies his front-office woes, while Jack flouts the team's routines and protocols.

Fellow expatriate player Max Dubois (Dennis Haysbert—yes, he was Serrano in Major League) offers exasperated advice, but when Jack spars with comely Hiroko (Aya Takanashi), who forces him to do an insipid television commercial as stipulated in his contract, their friction signals attraction as inevitably as a shuuto pitch induces Jack's swinging strikes—and just as inevitably, Hiroko turns out to be Uchiyama's daughter. Indeed, Jack's journey holds few surprises as he must overcome his batting slump and help the Dragons challenge the rival Yomiuri Giants for the pennant while he learns teamwork, humility, and respect—which we all know are sports-movie staples as requisite as the Big Game, which Mr. Baseball dutifully provides.

Really friends after all: Ken Takakura (left) and Tom Selleck in Mr. Baseball.

Director Fred Schepisi has a feel for the characters more so than for the game, although he does avoid most rookie mistakes, while veteran Jerry Goldsmith's score merely fills a roster spot. Selleck is serviceable, though he does swing a mean left-handed bat, with Takakura gaining strength in a sly sleeper performance as Mr. Baseball demonstrates that reliable sports clichés work in Japanese too.

At least Jack Elliot got to the Show. That's not a certainty, let alone a guarantee, for the players on the Durham Bulls, an actual Class-A team then in the Carolina League (although this story is fictional), save for one of them—if he can get his act together in time to make the late-season call-up to the Majors. Writer-director Ron Shelton knew of what he depicted in Bull Durham (5.0 WAR). As a second baseman, Shelton spent five years in the Baltimore Orioles farm system, working his way up to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings, and much of that experience gets channeled into one of the greatest baseball movies—hell, sports movies—ever made, not just because its portrayals of baseball ring with authenticity, but because its characters sing with distinction. making it a true Hall of Fame accomplishment.

Young girls don't get woolly, meat: Pitching phenom Nuke LaLoosh (Tim Robbins, left) and veteran catcher Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) don't always see eye-to-eye in Bull Durham.

Catcher Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) had a cup of coffee in the Show, but as a career minor-leaguer who never got another call-up, he has resigned himself to a more modest goal. However, that goal wasn't to be sent down to Class-A ball—and certainly not to mentor Ebby "Nuke" LaLoosh (Tim Robbins), a young, brash pitching phenom with Big League talent but Little League maturity. Resentful of Nuke for any number of reasons, Crash teaches him to respect his Hall of Fame arm, as well as to respect the game that can make him that Hall of Famer, with heated exchanges on the mound such as when Nuke, after shaking off Crash's call for a curve ball, says that he wants to "announce his presence with authority" with his fastball; that seemingly convinces Crash—who promptly tells the hitter what's coming next.

Economy or first class? Crash (Costner, left) and Nuke (Robbins) discuss accommodations on Nuke's gopher ball as Nuke learns another potentially big-league lesson in Bull Durham.

Complicating their already-adversarial relationship is Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon), a "baseball Annie" (to borrow the term Jim Bouton uses to describe a baseball groupie in his landmark exposé Ball Four) yet serial monogamist who selects Nuke as her lover for the season, to Crash's seeming chagrin. Nevertheless, she finds herself in league with Crash to prepare the mercurial Nuke for the Majors, and as Nuke's maturation improves the Bulls' fortunes, Annie and Crash see their initial mutual antagonism begin to dissolve.

Like most baseball plays, Bull Durham's love triangle offers routine, predictable reassurance, but it's the beauty inherent in the execution of those plays that fosters fans' admiration; similarly, Shelton makes nary an error in his depiction of the endless monotony legions of players endure in the hope of making it to the Majors—or not—with William O'Leary, Jenny Robertson, Trey Wilson, and Robert Wuhl bolstering the lineup. With Costner's quiet resignation providing the fulcrum, Sarandon's sexy eccentric balances Robbins's cocky bumpkin as Bull Durham not only displays its keen insight into the game, it celebrates all who worship in the church of baseball.

Bull Durham is notable for not only eschewing the obligatory Big Game, but, more importantly, for not even being set in the Major Leagues—in fact, it illustrates how difficult it is to even get to the Bigs, which only one of our previous movies, Big Leaguer, addressed seriously. But there was a time when it wasn't just talent—or a lack thereof—that kept a baseball player out of the Majors: the color of his skin automatically prevented that.

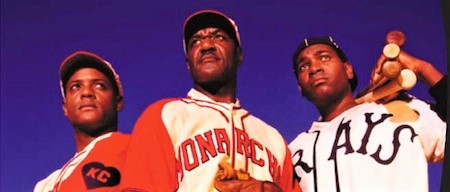

We have seen how The Jackie Robinson Story presented a sanitized, positive narrative of Robinson's historic achievement to become the first African-American Major Leaguer in the 20th century. Soul of the Game (3.3 WAR) broadens that scope to offer a salutary, sometimes bracing look at Robinson (Blair Underwood) and two other Negro League legends around the time of Robinson's 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers as it presents two of those legends, pitcher Satchel Paige (Delroy Lindo) and catcher Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson), as Robinson's de facto godfathers.

Negro Leaguers Jackie Robinson (Blair Underwood), Satchel Paige (Delroy Lindo), and Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson) contemplate the Soul of the Game.

Scripting Gary Hoffman's story, David Himmelstein illuminates the three against the backdrop of their personal and professional contemporaries with a series of pointed sketches that tend to overemphasize the emotions to the point of melodrama. Director Kevin Rodney Sullivan exacerbates that tendency with clipped, consciously underlined segments that encourage his cast to goose their performances, affectation that detracts from an otherwise-effective dynamic.

Paige, seemingly ageless yet clearly aging, and Gibson, supremely talented yet tormented by inner demons, spar as rivals on the diamond but foster their mutual ambitions off the field, foremost being their determination to play in the Majors. Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey (Edward Herrmann, in typically excellent form) is scouting Negro Leaguers for that goal, but he chooses Paige's teammate Robinson—younger, college-educated, more resilient temperamentally—to make that breakthrough, which only makes the increasingly-erratic Gibson more truculent, highlighted in scenes that might aim for poignancy but instead play as heavy-handed manipulation.

Rivals on the field, Satchel Paige (Delroy Lindo, pitching) and Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson, batting) both shared dreams of Major League glory.

Robinson remains the focus of Soul of the Game but a charismatic Lindo gets to display the most dimension as his Paige, a savvy showman and businessman, sublimates the indignities of segregation into his determination to succeed as Williamson, his Gibson struggling to articulate his frustrations, must weather an underdeveloped part; meanwhile, Salli Richardson-Whitfield, as Lahoma Paige, and Gina Ravera, as Grace, Gibson's girlfriend already married to another man, are saddled with the obligatory supportive-women roles, with Lee Ermey, Jerry Hardin, and Richard Riehle filling out the roster. Stringing together one carefully crafted teachable moment after another, Soul of the Game delivers laudable life lessons but falls short of an effective, engaging narrative.

Another barrier to entry into the Majors, whether around the time of Soul of the Game or at any other time, is gender. But as the United States entered World War Two in December 1941, the fate of the 1942 baseball season (as we are experiencing in 2020, although because of an entirely different kind of enemy) was seriously in question. Both major and minor leaguers were joining the ranks of millions of American men entering the armed forces, thinning not only rosters and bleachers but also forcing the decision of whether it was appropriate, or indeed patriotic, to continue playing Major League Baseball during time of war.

President Franklin Roosevelt ultimately decided that, yes, baseball was deemed essential to the war effort as a morale-booster for both the home front and the armed forces overseas. And just as women were moving en masse into wartime jobs in both public and private sectors, so too did women move into baseball. Formed in 1943, The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was initially conceived as a replacement for Major League Baseball, but with no interruption to MLB, the AAGPBL still went ahead, lasting until 1954.

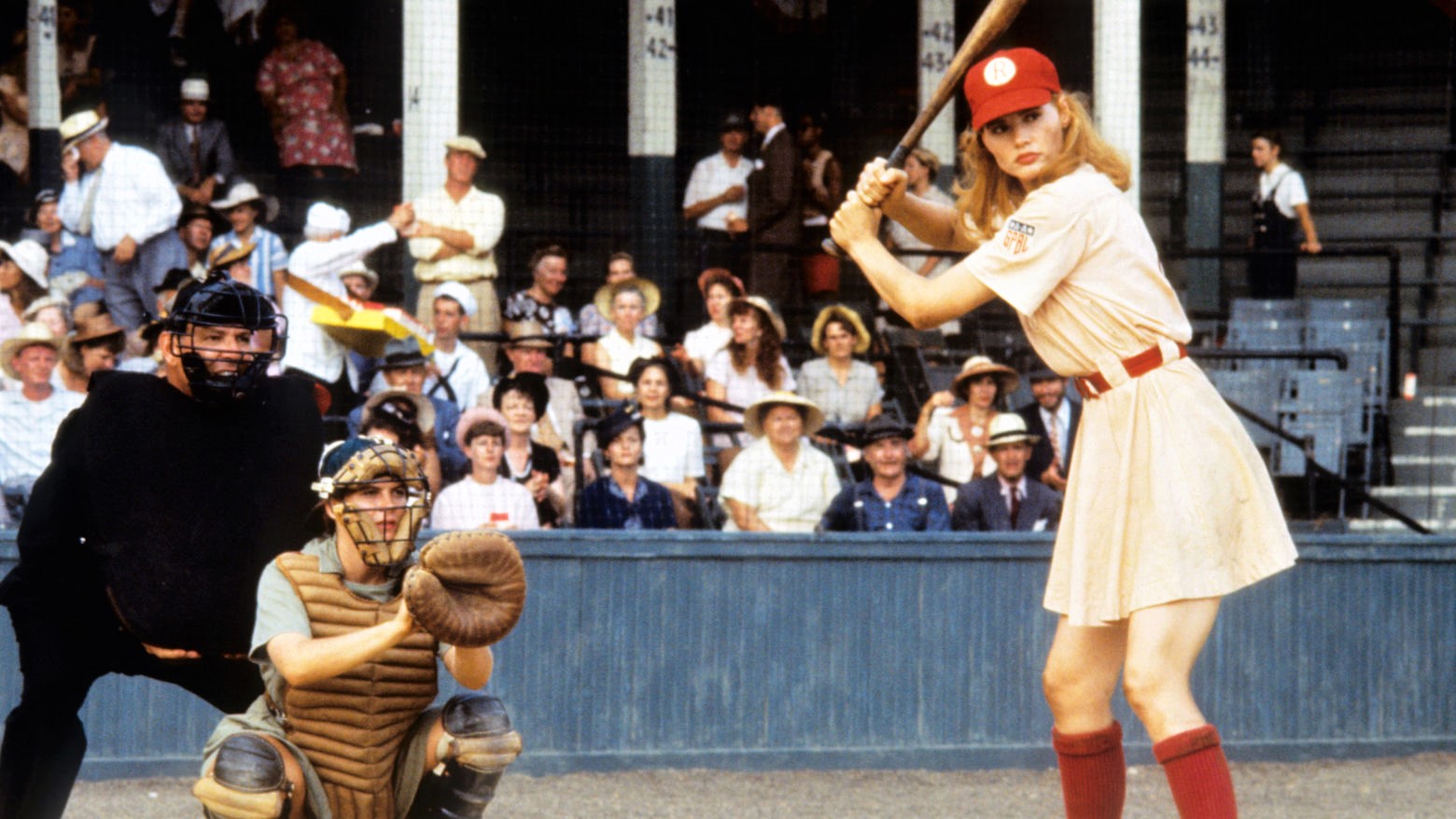

Penny Marshall was inspired to make A League of Their Own (4.5 WAR) after watching a 1987 documentary of the same name about the AAGPBL, which she—like so many others including me—had never heard of before. She commissioned screenwriters Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel to work with the documentary's creators, Kelly Candaele and Kim Wilson, to script a fictionalized account of the league centered around a sibling rivalry between Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis), a hard-hitting catcher, and her kid sister, pitcher Kit Keller (Lori Petty).

Dirt in the skirt: Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis, batting) shows how the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League gets it done in A League of Their Own.

Make no mistake. Marshall, sister of television producer Garry Marshall, is nothing if not a product of television; even if she did establish a career as a feature-film director, Marshall still retained a sitcom sensibility, as did Ganz and Mandel, who wrote for Marshall's Laverne & Shirley comedy series as well as for the big screen. As a result, everything about this baseball comedy-drama conforms to sports movie cliché, right down to the finale's big-game showdown that pits the two principals against each other. Yet Marshall and her cast shine here because of the film's laudatory subject—and Marshall, ever-generous, even finds roles for her former Laverne & Shirley castmates Eddie "the Big Ragu" Mekka and especially David L. "Squiggy" Lander as a radio announcer broadcasting the games.

Oregonian farm girl Dottie is a phenom catcher whom scout Ernie Capadino (a scene-stealing Jon Lovitz) recruits for the new league; Dottie insists that her kid sister Kit, a pitcher, must come as well. In Chicago for tryouts, Dottie and Kit join saucy speedster Mae Morabito (Madonna), brash basher Doris Murphy (Rosie O'Donnell), and homely heavy-hitter Marla Hooch (Megan Cavanaugh), among others, on the Rockford Peaches, one of four teams in the league created by candy mogul Walter Harvey (Garry Marshall), based on real-life sponsor P.K. Wrigley, and run by believer Ira Lowenstein (ever-reliable David Strathairn, whom we'll see shortly in a more prominent role), who keeps the league afloat when initial interest sours.

Combing the sticks for talent: Baseball scout Ernie Capadino (Jon Lovitz) makes his pitch to Dottie and her sister Kit in A League of Their Own.

Tom Hanks is terrific as Jimmy Dugan, an alcoholic former big-league slugger, loosely based on Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx, tapped to manage the Peaches; his professional relationship with Dottie forms the heart of this movie along with Dottie and Kit's rivalry, which culminates in the big-game showdown as Ganz and Mandel keep the slick dialog flowing around both slapstick and sentiment. There might not be any crying in baseball, but A League of Their Own pitches its heartwarming laughs right across the plate.

Game's gettin' excitin', huh? (L-R) Pitcher Kit Keller (Lori Petty), manager Jimmy Dugan (Tom Hanks), and catcher Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis) confer in A League of Their Own.

One brief scene in particular shines for me, consciously crafted as one of those lump-in-the-throat moments that still does its job. During the tryouts at Wrigley Field, a ball rolls out to the warning track, near where an African-American woman is walking; she's well-dressed but clearly not included in the all-white activities as baseball, even at the AAGPBL level, is still segregated. She retrieves it—then uncorks a Roberto Clemente-like throw that sails into the infield, where Dottie catches it. All it takes are two silent nods—the black woman's nod of assertion, and Dottie's nod of acknowledgement—for the tingling to blossom at the back of my neck. And talk about attention to detail—check out how instinctively Marla backs up the play behind Dottie.

Marla Hooch--what a hitter! Actually, homely heavy-hitter Marla (Megan Cavanaugh) can flash a little leather out there at second base, too.

Actual events and personages also inform Eight Men Out (5.0 WAR), based on Eliot Asinof's true account of how eight players on the Chicago White Sox conspired with gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series and thus trigger a monumental scandal whose repercussions reverberate even today. Just ask Pete Rose about that.

Who are the White Sox and who are the "Black Sox"? Eight players helped gamblers fix the 1919 World Series in the historical drama Eight Men Out.

Recall from the Vintage Era how sportswriter Ring Lardner was haunted by this 1919 "Black Sox" scandal that rocked not just baseball but American society (Fitzgerald's "faith of fifty million," remember?). Two of Lardner's stories made into baseball vehicles for Joe E. Brown, Elmer, the Great and Alibi Ike, featured gamblers angling to corrupt Brown's talented rube, with the real-world analog being White Sox star outfielder "Shoeless Joe" Jackson, whose lifetime batting average of .356 is topped only by Ty Cobb's (.367) and Rogers Hornsby's (.358), but whose involvement in the scandal has still kept him ineligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame. A fan favorite, Jackson's saga is encapsulated by the (in)famously apocryphal newspaper account (demonstrating that "fake news" has always been with us, but I digress) of kids confronting their hard-hitting idol after revelations about his helping to throw the World Series, with one pleading, "Say it ain't so, Joe," to which Jackson must reply that it is.

Say it ain't so, Joe: Buck Weaver (John Cusack, left) gets caught in the middle of the scandal that also implicated superstar Joe Jackson (D.B. Sweeney).

Still, it's an account too good not to include in Eight Men Out as John Sayles not only wrote and directed this rich dramatization of the scandal, he portrays Ring Lardner as he and fellow sports reporter Hugh Fullerton (Studs Terkel) start keeping track when they realize that a fix must be on as the heavily-favored White Sox—a powerhouse team that finished 36 games above .500 to win the 1919 American League pennant (yet finished only 3.5 games ahead of a Cleveland Indians squad that featured future Hall of Famers Stan Coveleski and Tris Speaker)—start to struggle against the underdog Cincinnati Reds. (In actuality, the Reds finished 52 games above .500 and nine games ahead of the New York Giants—in other words, they hardly scraped into the World Series.)

With cinematographer Robert Richard applying the appropriate sepia tones, Eight Men Out harkens back to the vintage days of baseball although it is poles apart from the myths and melodramas of bygone baseball films. Sayles betrays not a whiff of nostalgia or sentimentality as he strives to convey both the burgeoning Jazz Age and the World Series diamond with realistic verité, succeeding impressively with an overarching ambition and attention to detail along with the actors' engaged portrayals and overall baseball-playing believability.

White Sox owner Charles Comiskey (Clifton James) assembles a championship team managed by former player Kid Gleason (John Mahoney), but his notorious parsimony made some players susceptible to offers to throw the World Series and thus lose it for more money than they would make for winning it. Although the term "Black Sox" came to describe the 1919 White Sox once the scandal came to light, it appears to have been used prior to the Series to describe the team. Not that the team was taking dives or cheating (there have been no reports of trash cans being banged during White Sox home games in 1919, for instance), but they may have been "playing dirty": Comiskey was such a skinflint that he actually made the players pay for their own laundry (calling Indians owner Rachel Phelps from Major League!), so in protest they allegedly played with dirty uniforms including "black socks."

"Black Sox" in more ways than one: The White Sox try to turn two the gritty way as part of the on-field baseball action in John Sayles's Eight Men Out.

Enter Boston gambler Sport Sullivan (Kevin Tighe) and a pair of his small-time grifters, "Sleepy" Bill Burns (Christopher Lloyd) and Billy Maharg (Richard Edison), who learn of the Sox's disgruntlement with Comiskey and broach an offer with first baseman Chick Gandil (Michael Rooker) to play poorly in the upcoming World Series in exchange for a bigger payoff ultimately supplied by legendary racketeer Arnold Rothstein (Michael Lerner). Needing more key players to help put the fix in, Gandil recruits pitcher Lefty Williams (James Read), infielders Swede Risberg (Don Harvey) and Fred McMullin (Perry Lang), and outfielders Happy Felsch (Charlie Sheen) and, haltingly, Joe Jackson (D.B. Sweeney).

Two other players prove pivotal. One is infielder Buck Weaver, who is aware of the fix but plays cleanly in the Series—although neither does he come clean about his knowing that there was a fix in place. John Cusack portrays Weaver as Sayles's fulcrum in Eight Men Out, its conscience conflicted by loyalty to his teammates, all with a mutual animosity toward Comiskey, and by his need to respect the game and, at the risk of waxing too grandiose, maintaining the faith of those fifty million Americans in the national pastime. By turns petulant, cowed, and outraged, Cusack acquits himself convincingly.

The other is pitcher Eddie Cicotte (David Strathairn), around whom Sayles structures Eight Men Out, first because, historically, Cicotte was a crucial cog in the fix. The knuckleballing right-hander (unsurprisingly, his nickname was "Knuckles") led the Majors in wins and winning percentage in 1919 with a 29–7 record, good for an .806 win-loss percentage, while posting a 1.82 ERA; he also paced the Majors with 30 complete games and 306.2 innings pitched, inconceivable seasonal numbers a century later but hardly unusual as the dead-ball era drew to a close. Cicotte was clearly the ace of the White Sox rotation, as he had been when the White Sox won the 1917 World Series against the New York Giants, and having him on the side of the conspirators would almost guarantee success.

Sayles also structures Eight Men Out around Cicotte because David Strathairn is a marvelous actor who conveys the gravity of the decision to throw in with the fixers. The keynote scene comes during Cicotte's confrontation with Comiskey over a term in his contract: Cicotte would get a $10,000 bonus if he won 30 games during the 1919 season (by the way, $10,000 in 1919 would be worth nearly $150,000 in 2020), but Comiskey had ordered Gleason to bench Cicotte for two weeks, during which time he would have started about five games, with the rationale being that he needed to rest Cicotte's arm for the World Series. Cicotte argues that he was likely to win at least one game during that stretch and thus would have won 30 games, but Comiskey—and veteran character actor Clifton James turns in a fine performance as the de facto real villain in this tale—tells him that, "twenty-nine is not thirty, Eddie." The range of emotions subtly but unmistakably passing across Strathairn's outwardly impassive face—disbelief, anger, and finally resignation—signals Cicotte's fateful decision. Thus the fix goes forward.

Chicago White Sox pitcher Eddie Cicotte faces the moment of truth in the 1919 World Series as David Strathairn becomes the center of Eight Men Out.

Of course, the majority of the White Sox players were clean, with second baseman Eddie Collins (Bill Irwin) and especially catcher Ray Schalk (Gordon Clapp), both future Hall of Famers, smelling something fishy on the diamond. And what of Joe Jackson? In actuality, Shoeless Joe led all hitters in the Series who had more than six at-bats with a .375 average including three doubles and the only home run hit in the Series by either team as he scored five runs and drove in six. Portraying Jackson, D.B. Sweeney captures his halting, uneducated manner without caricature while Clapp, a John Sayles regular, keeps the chatter strong—and accusing, once he realizes that some of his teammates are betraying him.

(Schalk, voted into the Hall of Fame in 1955 by the Veterans Committee, was one of the few players who made it into Cooperstown purely on his defensive play; for instance, he is credited with being the first catcher to back up first base on infield grounders. As a hitter, though, "Cracker" Schalk batted .253 lifetime with 11 home runs. Not exactly knocking down the fences. However, in 1919 he hit a career-high .282, and in the World Series he batted .304. Meanwhile, "Cocky" Collins, who hit .333 lifetime and whose 3315 career hits rank 11th all-time, hit just .226 in the 1919 World Series.)

To be sure, Eight Men Out is not perfect. Non-baseball fans might be awash in the details, some of which are too subtle for ready understanding, while the ramifications of the scandal, including the trial that saw all eight players acquitted of the conspiracy to defraud charges, and the appointment of baseball's first commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis (John Anderson), who subsequently banned all eight players from baseball for life, get a rushed denouement.

But as this is the first movie for which I've given more than just a capsule evaluation, not only do I think that Eight Men Out, which revisits the nostalgia-laden Vintage Era with anything but gloppy sentiment, is one of the greatest baseball movies ever, willing to expose one of the darkest chapters in the long history of this venerable sport, it does so with clear-eyed (if not always clear-spoken) discernment borne not of contempt for the game but rather of love for it. If you haven't guessed, this is the movie that I bumped up to Hall of Fame-level WAR, but given its historical importance and professional execution, it wasn't that far from the threshold in the first place.

Remember Shoeless Joe? Well, he factors into another baseball movie, which has to be one of the most overrated baseball movies ever. I speak, of course, about the movie that can make grown men weep as they plow under their corn fields to make way for a baseball diamond. I cried, too, when I first watched Field of Dreams (2.0 WAR), but that was because I couldn't believe that such overweening, bathetic tripe was being passed off as a movie meant to appeal to anyone over the age of seven.

Recently, I tuned into the MLB Network and saw movie critic Jeffrey Lyons sitting on a panel of the network's hosts and analysts. Naturally, they were discussing baseball movies, and, inevitably, Field of Dreams came up. Cue the violins as the hankies came out; to a man, they cited it as their favorite baseball movie. The irony is that in an age of sabermetrics, that objective, analytical methodology often dismisses—and often with sneering arrogance—any kind of subjective, intangible, or emotional factors (usually described by body parts such as "heart" or "guts") to describe player performance—but apparently that all gets saved for singing the praises of manipulative glurge like this.

The ultimate in fantasy baseball? Disgraced White Sox players get a second chance in Field of Dreams, which promises baseball heaven but delivers Iowa corn instead.

Writer-director Phil Alden Robinson must have understood that baseball legacy often approaches mythology when he adapted W.P. Kinsella's magical-realism novel Shoeless Joe because he perpetuates that tendency with no hint of shame or self-consciousness, delivering this heap of cornfed sentimentality that also lards the narrative with paeans to the 1960s amidst attempts at hardball realism.

In his Iowa cornfield, farmer Ray Kinsella (Kevin Costner) hears a voice intone, "If you build it, he will come," with visions of a baseball field coming later. Initially skeptical, wife Annie (Amy Madigan) lets him plow under valuable crops to build it; eventually, deceased and disgraced superstar Shoeless Joe Jackson (Ray Liotta) appears on the field. Soon Jackson's 1919 "Black Sox" teammates join him for the ultimate in fantasy baseball. (And somewhere in the transition from one dimension to another, Shoeless Joe learned to bat right-handed. Not only that, but Southerner Jackson picked up a New York accent along the way. Maybe that's proof that he did consort with Eastern gamblers?)

Me a cheatah? Fuggedaboudit. Ray Liotta's Shoeless Joe Jackson, a Southerner who hit lefty and threw righty, picks up some odd traits crossing dimensions in Field of Dreams.

Then the voice spurs Ray to Boston to locate Terrence Mann (James Earl Jones), a J.D. Salinger stand-in, and "ease his pain." Mann was a miss, but they both get the message to proceed to Minnesota to seek out Moonlight Graham (Burt Lancaster), now an elderly physician but denied a real chance at the Major Leagues as a young man. Graham wasn't it, either, but then they pick up young, ballplaying hitch-hiker Archie Graham (Frank Whaley). Oh, look—there's that name again. Meanwhile, back on the home front, brother-in-law Mark (Timothy Busfield) warns of farm foreclosure.

Terrence Mann (James Earl Jones, right) still manages to look askance at Sixties throwback Ray Kinsella (Kevin Costner), but just wait until he visits Ray's magical Field of Dreams.

Costner is agreeably bland as the cockeyed crusader willing to bet the farm, quite literally, on an obsessive father fixation. In a thankless role as the practical wife and mother to glaring plot-device daughter Karin (Gaby Hoffman), Madigan gets a few good lines, particularly as a defender of free thought and expression at a contentious school assembly that lacks only torches and pitchforks (this is Iowa, after all), before receding into the background.

Jones, too, gets a strong start. In fact, my favorite moment comes when Ray, having uncovered Terrence's urban lair in Boston, stumbles into Terrence's trap: Listening to Ray's idealistic spiel, Terrence stops him. "Oh, my God," he gasps. "You're from the Sixties." Then, picking up an old-style insecticide sprayer we've all seen in Bugs Bunny cartoons, he exclaims, "Out! Back to the Sixties! Back! There's no place for you in the future! Get back while you still can!" Too bad that Jones's refreshingly bracing introduction inevitably melts into the treacle at the field of dreams.

Look, I get it: First and foremost, Field of Dreams is a fable that delivers life lessons, from Graham's Wrenching Dilemma to Ray's Heartfelt Reconciliation with his distanced father (Dwier Brown). That may excuse the lack of logos but not the surfeit of pathos that, thanks to a perfectly plangent score by ubiquitous industry abettor James Horner, inevitably becomes bathos. Field of Dreams promises baseball heaven; instead, it delivers Iowa corn.

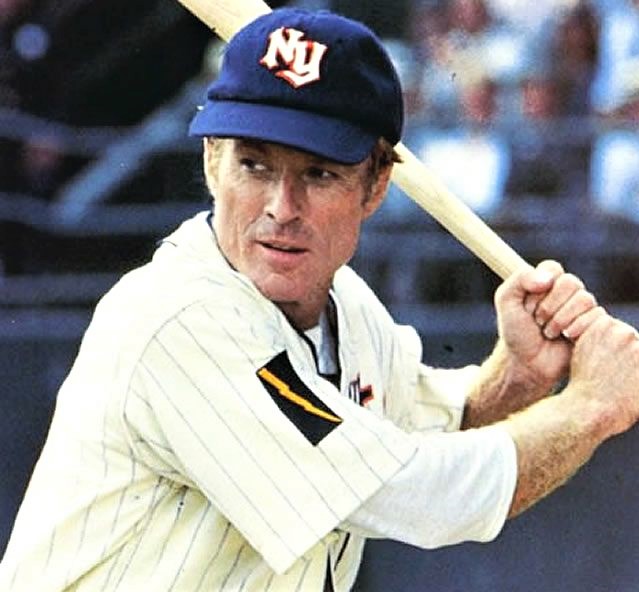

The corny roots of Field of Dreams lay in The Natural (3.2 WAR), which comes dangerously close to that movie's overblown histrionics as everything about The Natural screams mythic. Too much so. Yet the underplaying by the cast—sometimes too much so—keeps this period baseball epic, which is largely but not entirely faithful to Bernard Malamud's 1952 novel, from being sent to the showers. Director Barry Levinson sets a stately pace—sometimes too much so—for Phil Dusenberry and Roger Towne's adaptation of how Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford) goes from young phenom to middle-aged rookie while alluding to the true-life incidents of Eddie Waitkus and—here's that man again—Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Robert Redford takes his turn at-bat as Roy Hobbs, a Shoeless Joe Jackson stand-in, in The Natural.

After learning baseball down on the farm from his father (Alan Fudge), then leaving childhood sweetheart Iris (Glenn Close) behind, Roy heads to Chicago for his tryout with the Cubs. At a whistle stop along the way, he gets off the train and wows baseball star "the Whammer" (Joe Don Baker) and sportswriter Max Mercy (Robert Duvall) when Hobbs strikes out the Whammer on three pitches. In Chicago, however, before he can even get to the tryout, Roy is shot in his hotel by the Mysterious Woman in Black (Barbara Hershey) who had been on the train mooning over Hobbs after he had bested her previous obsession, the Whammer, whose moniker suggests a Babe Ruth-like nickname but sounds more like a failed breakfast special at Denny's (although Baker looks more Ruthian than did William Bendix in The Babe Ruth Story).

This parallels the actual June 1949 occurrence that befell Eddie Waitkus, the Cubs' promising first baseman—he had even been referred to as "the natural" when he came up—who had been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies the previous season. Back in Chicago for a game against the Cubs, Waitkus was lured to the room of Ruth Ann Steinhagen, an obsessive stalker who shot him in the chest. The bullet just missed his heart but Waitkus not only survived, he continued to play in the Majors until 1955. And like many of his generation, Waitkus served with distinction in the US Army during World War Two, earning four Bronze Stars while seeing fierce action in the Philippines.

However, The Natural uses the Waitkus incident, filled with drama all its own, solely as a plot point, and a tenuous one at that because the narrative immediately leaps ahead several years to present Roy as a middle-aged rookie who signs as an outfielder with the lowly New York Knights. With Hobbs foisted onto him by shadowy Knights owner "the Judge" (Robert Prosky), crusty Knights manager Pop Fisher (Wilford Brimley) grudgingly pencils Hobbs into the lineup, whereupon he becomes the Knights' savior with his slugging helping to lift them out of the cellar and into pennant contention.

Put me in coach, I'm ready to play (L-R): Robert Redford ("Roy Hobbs") makes his case to Wilford Brimley ("Pop Fisher") and Richard Farnsworth ("Red Blow") in The Natural.

Ah, but now cue Joe Jackson because the shadowy Judge—and I do mean shadowy as he seems never to have any light in his office—is consorting with shady gambler Gus Sands (an oddly uncredited Darren McGavin) in an internal fix: Pop has part-ownership in the Knights, but if they don't win the pennant, Pop's share reverts to the Judge. The Judge had been bribing right fielder Bump Bailey (Michael Madsen) to help sabotage the team, but Bump's lack of hustle spurs Pop to bench him during a game, and Roy literally knocks the horsehide off the ball while pinch-hitting for Bailey. Hold on—The Natural's overwrought symbolism gets better: Disgruntled at being benched, Bailey is so determined to show hustle to Pop that he runs straight through a wall while chasing a fly ball. That kills him. Really. It's not a joke. So, guess who becomes the starting right fielder?

And guess whom the Judge approaches with the same offer to spoil the Knights' pennant chances? To sweeten the pot, Pop's niece Memo Paris (Kim Basinger), Bailey's former squeeze, now comes on to Roy, who naturally can't resist Memo's abundant charms. (Didn't Hobbs get the memo about Wacky Waters way back in the Vintage Era's Ladies' Day?) Just as naturally, the Knights begin to falter as the season draws to a close.

Now The Natural's already-dubious symbolism thickens with not one but two Women in White. First up is Memo, whose femme fatale wiles complement the filmnoir moodiness of Caleb Deschanel's semi-sepia color photography. Next comes Iris, who reappears in Roy's life with some not-so-surprising news that might offer another reason why Roy was so all-fired anxious to get on that train to Chicago way back when; now Deschanel backlights Close with almost Biblical reverence (in fairness, Close had just come off playing a near-saintly character in 1983's OK Boomer-fest The Big Chill), all while Randy Newman's portentous score heralds the final fireworks. However, Redford's credibility builds on and off the diamond—he looks pretty natural swinging a left-handed bat—as he keeps The Natural's burgeoning pomposity in the ballpark.

In case you miss the symbolism in The Natural, cinematographer Caleb Deschanel makes sure Glenn Close ("Iris Gaines") gets backlighting fit for a saintly Woman in White.

Comments powered by CComment