Index

2018: Johnny Damon, Andruw Jones, Jamie Moyer, Johan Santana, Scott Rolen, Omar Vizquel

The 2018 ballot offers two first-time candidates, Chipper Jones and Jim Thome, whose elections to the Hall of Fame are both likely on this ballot and all but certain on a subsequent ballot if not. Moreover, there should be a thinning of the ballot in comparison to previous years.Could this spell hope for our six borderline candidates?

Johnny Damon and Andruw Jones

Center fielders have not fared well on the Hall of Fame ballot in recent years—Jim Edmonds, Steve Finley, and Kenny Lofton did not survive their first ballot appearance while Bernie Williams was gone by his second chance—but the 2018 ballot has two first-time center fielders, Johnny Damon and Andruw Jones, who could not be more different although they do share one unusual distinction: In 2002, each was the 30th player selected for their league's respective All-Star team through an online vote by fans, the first time such a vote had been held; Damon, then on the Boston Red Sox, was the American League's 30th player while Jones, a member of the Atlanta Braves, represented the National League.

Johnny Damon's early career had the hallmarks of a star player on the rise. Starting in 1995, he spent his first six seasons with the Kansas City Royals, becoming a full-time player in 1996, honing his skills and adjusting to the Major Leagues, which culminated in 2000 when he led the AL in runs scored (136) and stolen bases (46), both career highs, as he racked up 214 hits, another career high and his only 200-hit season, including 42 doubles, 10 triples, and 16 home runs, all good for a .327/.382/.495/.877 slash line, that last percentage his OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) that generates a 118 OPS+, and a 115 wRC+. In his six seasons with the Royals, Damon averaged 149 hits per year including 26 doubles, 8 triples, and 11 home runs, with 84 runs scored and 26 stolen bases. Over that period, Damon posted a .292/.351/.438/.789 slash line but a 101 OPS+, essentially league-average.

Part of a three-way trade in 2001, Damon moved to the Oakland A's where his effectiveness dipped significantly despite scoring 108 runs. The following season, now a free agent, Damon signed a four-year contract with the Red Sox, becoming a part of the "idiots" who would go onto an epic heartbreak in the 2003 AL Championship Series against Boston's bitter rivals the New York Yankees before breaking the Curse of the Bambino the following season in a truly historic postseason that saw them clinch their first World Series in 86 years.

In his four-year stint with the Red Sox, Damon, in his age-28 through age-31 seasons, generated a .295/.362/.441/.803 slash line with a 108 OPS+ as he averaged, per season, 182 hits including 34 doubles and 14 home runs along with scoring 115 runs and swiping 24 bases. Damon led the AL in triples (11) in 2002 and in 2005 banged out 197 hits, fifth in the American League, while his 117 runs scored was fourth in the league, as was his .316 batting average, the fourth of five times that he would hit .300 or higher in his career. However, his previous season, the 2004 championship season, may be Damon's most solid overall as he posted a .304/.380/.477/.857 slash line, which yielded a 117 OPS+, while he established career highs in walks (76) and runs batted in (94) while hitting at least 20 home runs for the first of three times in his career.

The 2004 postseason found Damon winning the first of two World Series rings during Boston's historic, dramatic year that saw the Red Sox lose the first three games of the ALCS to the hated Yankees—only to win the next four games to move onto the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, the only time an MLB team had lost the first three games of a seven-game series but rebounded to eventually win the series. Damon's overall performance in the ALCS was unremarkable, notching just 6 hits in 35 at-bats, including 8 strikeouts, for a .171 batting average—however, two of those hits were home runs, both coming in the decisive Game Seven, with the first a second-inning grand slam that put the nail in the Yankees' coffin, all the more damaging as it occurred in Yankee Stadium.

Johnny Damon would go on to see much more of Yankee Stadium: At the end of 2005, he signed a four-year contract with the Bronx Bombers, and the center fielder hitting-machine's ascendancy to the top of the baseball world, begun in lowly Kansas City with stops in Oakland and Boston, seemed complete. Of course, Damon incurred the wrath of the Fenway faithful—who had voted him to the AL All-Star squad in 2005, his second and final selection—as he had sworn earlier in the year that he would never play for the Yankees, but he was hardly unique in that as Red Sox icons Wade Boggs and Roger Clemens, and later Jacoby Ellsbury, all played for the Yankees following their tenure in Boston.

With his stint with the Yankees coinciding with his decline phase, Damon still generated a .285/.363/.458/.821 slash line, good for a 112 OPS+, while averaging 159 hits, including 31 doubles and 19 home runs, 102 runs scored, and 23 stolen bases over his four seasons in the Bronx. His .303 batting average in 2008 was his fifth and final season of hitting .300 or higher while he hit 24 home runs in a season, his career high, twice, in 2006 and again in 2009.

For the Yankees in the 2009 postseason, Damon managed just one hit in 12 at-bats against the Minnesota Twins in the AL Divisional Series, which the Yankees swept despite him, but he came alive against the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim as he hit two home runs, drove in five runs, and batted .300 during the six games that saw New York advance to the World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies, looking to defend their world championship. Damon batted a torrid .364, scored six runs, and drove in four more as the Yankees won their first World Series ring since 2000 in six games, with Damon stealing three bases—including two in the same play against the Phillies' overshift that left third base unattended.

Unable to come to terms with the Yankees at the end of the 2009 season, Damon, by now a left fielder and designated hitter, spent a season each with, respectively, the Detroit Tigers, Tampa Bay Rays, and Cleveland Indians before the MLB jobs dried up after 2012. In his 18-year career, Johnny Damon finished 31st in runs scored (1668), 46th in doubles (522), 53rd in hits (2769), 67th in stolen bases (408), and 128th in triples (109). He had 10 years with 100 or more runs scored, nine of those consecutively from 1998 to 2006, and 12 years with 150 or more hits, with nine of those seasons, not surprisingly, also between 1998 and 2006.

Defensively, Damon was never an asset although the move to left field during his decline phase boosted his effectiveness. His overall defensive WAR (dWAR), computed by Baseball Reference, of –3.1 reflects his liability in the field, as reinforced by his Total Zone total fielding runs above average (Baseball Reference) in center field at –35 runs, with his defensive runs saved (Baseball Reference) at the same position as –28 runs, both for the 1298 games Damon played in center field, although he looks better in left field (684 games played) with 48 runs and 8 runs, respectively.

On the other hand, Andruw Jones, who at least during the first 12 years of his 17-year career, appeared to be the poster boy for advanced defensive metrics, at one point emerging as one of the greatest defensive players ever, although subsequent reassessment has brought the slugging center fielder down from such Olympian heights. Nevertheless, Jones, a native of the Caribbean island of Curaçao who first appeared in his age-19 season in 1996 with the Atlanta Braves and who finished fifth in National League Rookie of the Year voting the following year, won ten consecutive Gold Gloves starting in 1997, putting him in a tie for second for the most Gold Gloves by an outfielder with Ken Griffey, Jr., Al Kaline, and Ichiro Suzuki—with the first two Hall of Famers and the last a certain one when he retires. Moreover, and unusual for a center fielder, Jones had a cannon for an arm and ranks 34th in assists (102) for center fielders.

How good was Jones as a defensive center fielder—and how bad was Damon? For comparative purposes, the following table details the following:

The FanGraphs and Baseball Reference Total Zone total fielding runs above average ratings, ranked by FanGraphs Total Zone for this sample, for center fielders currently enshrined in the Hall of Fame and (in bold italic) upcoming candidates Johnny Damon and Andruw Jones along with (in bold) recent Hall of Fame candidates Jim Edmonds, Steve Finley, Kenny Lofton, and Bernie Williams.

The FanGraphs Total Zone ratings are for center field unless marked by an asterisk (*), which indicates that only overall outfield data is available. For Baseball Reference Total Zone, no data is available for players up to the 1950s.

Also listed is Defensive Runs Saved, from Baseball Reference, although data is only available for recently retired players; all others are listed with an NA for not applicable.

Finally, the player's defensive Wins Above Replacement (dWAR), as calculated by Baseball Reference, is listed. Please note that dWAR takes into account the player's defensive rating at any position he played and is not exclusively for center field.

| Rank |

Player |

Total Zone (FanGraphs) |

Total Zone (Baseball Reference) |

Defensive Runs Saved (Baseball Reference) |

Defensive Wins Above Replacement (Baseball Reference) |

| 1 |

Jones, Andruw |

220 |

220 |

61 |

24.1 |

| 2 |

Mays, Willie |

148 |

176 |

NA |

18.1 |

| 3 |

Lofton, Kenny |

119 |

115 |

–21 |

14.7 |

| 4 |

Speaker, Tris |

91* |

NA |

NA |

2.5 |

| 5 |

Carey, Max |

86* |

NA |

NA |

–0.1 |

| 6 |

Edmonds, Jim |

83 |

80 |

–7 |

5.9 |

| 7 |

Dawson, Andre |

78 |

77 |

NA |

0.9 |

| 8 |

Duffy, Hugh |

68* |

NA |

NA |

–2.5 |

| 9 |

DiMaggio, Joe |

49* |

NA |

NA |

3.2 |

| 10 |

Hamilton, Billy |

30* |

NA |

NA |

–5.2 |

| 11 |

Combs, Earle |

6 |

NA |

NA |

–2.8 |

| 12 |

Griffey, Jr., Ken |

4 |

6 |

–42 |

1.3 |

| 13 |

Cobb, Ty |

0 |

NA |

NA |

–10.8 |

| 14 |

Finley, Steve |

–4 |

–16 |

–3 |

2.8 |

| 15 |

Ashburn, Richie |

–5 |

39 |

NA |

5.3 |

| 16 |

Roush, Edd |

–6* |

NA |

NA |

–6.1 |

| 17 |

Doby, Larry |

–8 |

–5 |

NA |

–0.1 |

| 18 |

Puckett, Kirby |

–12 |

–12 |

NA |

–1.0 |

| 19 |

Snider, Duke |

–20 |

–7 |

NA |

–6.0 |

| 20 |

Mantle, Mickey |

–26 |

–10 |

NA |

–10.1 |

| 21 |

Averill, Earl |

–32* |

NA |

NA |

–5.3 |

| 22 |

Wilson, Hack |

–32* |

NA |

NA |

–7.2 |

| 23 |

Damon, Johnny |

–35 |

2 |

–28 |

–3.1 |

| 24 |

Williams, Bernie |

–44 |

–108 |

–64 |

–10.3 |

Quite noticeably, Andruw Jones stands alone as a defensive superstar, even ranking higher than Willie Mays, who is considered to be the greatest center fielder, both offensively and defensively, of all time. Only Jones and Mays rank among the top 1000 fielders at any position in all-time dWAR, with Jones ranking 20th while Mays is tied for 63rd place.

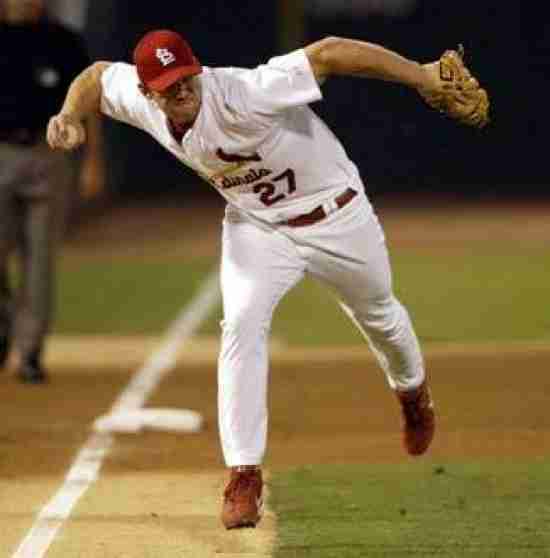

Advanced metrics place Andruw Jones among the greatest defensive center fielders of all time--but will his career nose-dive hurt him?

But defensive prowess, even at a strength position such as center field, is rarely the decisive factor in a Hall of Fame selection. Kenny Lofton, who had compiled an outstanding offensive record in addition to being one of the best defensive center fielders in the sample above, could not muster the necessary five percent of the vote to remain on a Hall of Fame ballot in his inaugural year—although that year happened to be 2013, when with a ballot overstuffed with qualified candidates, voters could not elect a single candidate to the Hall.

However, Andruw Jones, at least during his 12 seasons with the Braves, from 1996 to 2007, proved to be a potent offensive weapon certain to establish Hall of Fame credentials given that his final season in Atlanta, 2007, was only his age-30 season. In his time with the Braves, Jones compiled 1683 hits including 330 doubles and 368 home runs with 1045 runs scored, 1117 runs batted in, and 138 stolen bases. In a ten-year period between 1997 and 2006, Jones generated a .268/.346/.506/.852 slash line, yielding a 117 OPS+, while averaging, per season, 153 hits including 30 doubles and 34 home runs, 95 runs scored, 101 RBI, and 13 stolen bases.

The knocks against Jones was that he didn't hit for average—he batted at least .300 only once with a .303 average in 2000 when he fell one hit shy of the 200-hit plateau, his career high. That is not necessarily a negative in the sabermetric/Moneyball era, but neither was Jones working the count for bases on balls as he walked 80 or more times in a season only twice. Moreover, he struck out a lot, again not unusual in these free-swinging days, but he struck out at least 100 times in 11 consecutive seasons, and his 1748 career whiffs are tied for 22nd all-time.

However, Andruw Jones could hit for power, drive in runs, and at least early in his career could steal bases, all in addition to being a defensive superstar in center field. In 1998, his age-21 season, Jones hit 31 homers, and for the next nine consecutive seasons he hit at least 25 dingers every year, culminating with 51 big flies in 2005, which led the National League as did his 128 runs driven in, besting the St. Louis Cardinals' Albert Pujols in both categories while Jones finished second to Pujols in Most Valuable Player voting. Jones's 51 home runs remain a Braves single-season record—no small feat for a franchise that counts Hall of Famers Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews among its sluggers—and when Jones clouted 41 homers the following year along with 129 RBI, his career best, his ascendancy as an elite player establishing a Hall of Fame career seemed assured.

So, what happened? Jones's final season in Atlanta, 2007, saw him drop below league-average in both OPS+ (87) and wRC+ (86) with a paltry .222/.311/.413/.724 slash line although he did slug 26 homers while driving in 94. Weight and attitude problems were supposedly to blame, and when Jones wasn't re-signed by the Braves after the 2007 season, he signed as a free agent with the Los Angeles Dodgers. However, he reported to the Dodgers overweight and sustained a knee injury during a most inauspicious season that saw him, in only 75 games and 238 plate appearances, fall well below the Mendoza Line with an anemic .158/.256/.249/.505 slash line and only three home runs. More alarmingly, he was no longer an elite defender—his fielding runs above average fell into the negative range with –10 while his defensive runs saved dropped to –6 and his range factors, always previously better than the league's average, were now below-average.

In fact, Jones, with whom the Dodgers had negotiated a release, would finish the rest of his career as a corner outfielder, first with the Texas Rangers for a one-year stint before signing with the Chicago White Sox in 2010, then ending his Major League career in 2012 with the Yankees after signing with them in 2011. Jones did play two seasons in Japan before trying MLB comebacks in 2015 and 2016, then announcing his official retirement earlier this year.

Defensively among center fielders, Andruw Jones ranks 15th in putouts (4457), 34th in assists (102), and 40th in double plays turned (23), while his 434 home runs is tied for 44th on the all-time list.

In addition to the 20 Hall of Fame players identified by Jay Jaffe's JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) system as being a center fielder, the table below lists (in bold italic) Johnny Damon and Andruw Jones as well as recent Hall of Fame candidates (in bold) Jim Edmonds, Steve Finley, Kenny Lofton, and Bernie Williams. The players are ranked by JAWS, and the table includes other evaluation statistics, which are explained below the table, as well as the average aggregate bWAR and JAWS statistics for all center fielders already in the Hall of Fame.

| 2018 Center Field Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Center Fielders (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player |

fWAR |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Mays, Willie |

149.9 |

156.2 |

73.7 |

115.0 |

1 |

376 |

76 |

156 |

154 |

| Cobb, Ty |

149.3 |

151.0 |

69.0 |

110.0 |

2 |

445 |

75 |

168 |

165 |

| Speaker, Tris |

130.6 |

133.7 |

69.0 |

97.9 |

3 |

252 |

73 |

152 |

157 |

| Mantle, Mickey |

112.3 |

109.7 |

64.7 |

87.2 |

4 |

300 |

65 |

172 |

170 |

| Griffey, Jr., Ken |

77.7 |

86.6 |

53.9 |

68.8 |

5 |

235 |

61 |

136 |

131 |

| DiMaggio, Joe |

83.1 |

78.1 |

51.0 |

64.5 |

6 |

270 |

58 |

155 |

152 |

| Snider, Duke |

63.5 |

66.5 |

50.0 |

58.2 |

7 |

152 |

47 |

140 |

139 |

| Ave. of 20 CF HoFers |

NA |

71.1 |

44.5 |

57.8 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Lofton, Kenny |

62.4 |

68.2 |

43.3 |

55.7 |

9 |

91 |

42 |

107 |

109 |

| Jones, Andruw |

67.1 |

62.8 |

46.4 |

54.6 |

10 |

109 |

34 |

111 |

111 |

| Ashburn, Richie |

57.4 |

63.6 |

44.3 |

53.9 |

11 |

112 |

41 |

111 |

115 |

| Dawson, Andre |

59.5 |

64.5 |

42.5 |

53.5 |

12 |

118 |

44 |

119 |

117 |

| Hamilton, Billy |

70.3 |

63.3 |

42.6 |

53.0 |

13 |

154 |

51 |

141 |

142 |

| Edmonds, Jim |

64.5 |

60.3 |

42.5 |

51.4 |

14 |

88 |

39 |

132 |

132 |

| Doby, Larry |

51.1 |

49.5 |

39.6 |

44.6 |

20 |

72 |

30 |

136 |

137 |

| Damon, Johnny |

44.5 |

56.0 |

32.8 |

44.4 |

21 |

90 |

45 |

104 |

105 |

| Puckett, Kirby |

44.9 |

50.9 |

37.5 |

44.2 |

22 |

160 |

39 |

124 |

122 |

| Carey, Max |

60.1 |

54.2 |

32.9 |

43.6 |

25 |

76 |

36 |

108 |

110 |

| Williams, Bernie |

43.9 |

49.4 |

37.5 |

43.5 |

26 |

134 |

49 |

125 |

126 |

| Averill, Earl |

47.9 |

48.0 |

37.3 |

42.7 |

27 |

128 |

50 |

133 |

131 |

| Combs, Earle |

41.3 |

42.5 |

34.3 |

38.4 |

36 |

94 |

37 |

125 |

127 |

| Roush, Edd |

49.6 |

45.2 |

31.5 |

38.3 |

37 |

72 |

36 |

126 |

127 |

| Finley, Steve |

40.4 |

44.0 |

32.0 |

38.0 |

40 |

72 |

36 |

104 |

104 |

| Wilson, Hack |

42.1 |

38.8 |

35.8 |

37.3 |

43 |

100 |

39 |

144 |

143 |

| Duffy, Hugh |

48.3 |

43.0 |

30.8 |

36.9 |

46 |

155 |

55 |

123 |

118 |

| Waner, Lloyd |

25.0 |

24.1 |

20.3 |

22.2 |

116 |

86 |

31 |

99 |

99 |

| Hanlon, Ned |

19.2 |

18.0 |

14.2 |

16.1 |

163 |

12 |

12 |

102 |

104 |

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

WAR7: The sum of a player's best seven seasons as defined by bWAR; they need not be consecutive seasons.

JAWS: Jaffe WAR Score system—an average of a player's career WAR and his seven-year WAR peak.

JAWS Rank: The player's ranking at that position by JAWS rating.

Ave. HoF bWAR: The average bWAR value of all the Hall of Famers at that position.

Ave. HoF JAWS: The average JAWS rating of all the Hall of Famers at that position.

Hall of Fame Monitor: An index of how likely a player is to be inducted to the Hall of Fame based on his entire playing record (offensive, defensive, awards, position played, postseason success), with an index score of 100 being a good possibility and 130 a "virtual cinch." Developed by Baseball Reference from a creation by Bill James.

Hall of Fame Standards: An index of performance standards, indexed to 50 as being the score for an average Hall of Famer. Developed by Baseball Reference from a creation by Bill James.

OPS+: Career on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 OPS+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

wRC+: Career weighted Runs Created, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 wRC+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

Recent voting results for center fielders have exhibited a pronounced dichotomy. Ken Griffey, Jr., waltzed into the Hall of Fame with a record-setting vote tally and with qualitative statistics displayed in the table above that are well above the bar composed of aggregate results for all center fielders in the Hall. (The 19 Hall of Famers prior to Griffey's election composed an aggregate of 68.7 fWAR, 68.4 bWAR, 46.0 WAR7, and 55.7 JAWS.) However, of the preceding four center fielders on recent ballots, three never made it past their first year while the fourth, Bernie Williams, lasted only two years. Jim Edmonds and especially Kenny Lofton, though both beneath the bar, were truly borderline candidates; I had picked Lofton for the Hall in 2013, and I wouldn't complain if Edmonds were ever inducted.

An intriguing similarity between Ken Griffey, Jr., and Andruw Jones is that their peak period came early in their careers while they were playing for their first team, which was the team with which they played the majority of their careers. Each had a peak period of ten years, which is also the minimum length of Major League service needed to qualify for Hall of Fame consideration; for Griffey, that period was from 1990 to 1999, his age-20 to age-29 seasons, and for Jones, that period was from 1997 to 2006, also between his age-20 and age-29 seasons.

The table below compares selected qualitative statistics for Griffey and Jones based on their peak periods. The table also includes Johnny Damon although Damon's peak period is not as clearly defined, did not occur at the start of his career, nor occurred with just one team. Damon's ten-year period is 2000 to 2009, from his age-26 season, after he had been in the Major Leagues for five years, to his age-35 season, and it stretches across four teams.

| Ten-Year Peak-Period Comparison for Ken Griffey, Jr., Andruw Jones, and Johnny Damon, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Griffey, Jr., Ken |

.302/.384/.581/.965 |

.406 |

67.3 |

65.9 |

152 |

146 |

| Jones, Andruw |

.268/.346/.506/.852 |

.361 |

57.8 |

60.9 |

117 |

116 |

| Damon, Johnny |

.291/.360/.445/.805 |

.352 |

39.3 |

33.5 |

108 |

110 |

Just on his ten-year peak, Griffey would most likely be elected to the Hall of Fame with little effort while Jones would certainly be a much-discussed bubble candidate. Damon would likely not survive a first ballot.

In fact, Damon may remind you of Garret Anderson, evaluated in Part 1 of this series and determined to be a compiler. That's not an insult as any player has to be good enough to stay on a Major League roster in order to compile statistics significant enough to then be considered for the Hall of Fame; appropriately, Damon and Anderson each hit the same number of doubles, 522, in their careers. But Johnny Damon, despite some high-profile moments, was at best a notch or two above a league-average player, again, not an insult, but also not a Hall of Famer.

Andruw Jones, who by statistical coincidence hit the same number of doubles, 383, as Kenny Lofton, is not so easily pigeonholed. Unlike Damon, his traditional numbers are not impressive—he fell 67 hits shy of 2000, and his .254/.337/.486/.823 career slash line is unremarkable. Yet he hit 434 home runs, 337 of those during his ten-year peak, and 368 of those during his 12 years with the Atlanta Braves. Moreover, Jones, at least by modern defensive metrics, is considered to be one of the greatest defensive center fielders of all time with ten consecutive Gold Gloves to his name. And Jones's early, sustained peak looks most impressive—enough to make his dramatic decline in his last few seasons look like a debilitating liability.

Andruw Jones is hardly the only player who got off to a Hall of Fame-like start before collapsing; Nomar Garciaparra is a recent example, and we will see shortly whether Johan Santana is another example. To get into the Hall of Fame, a player must not only be very good—significantly better than league-average—but be very good for a very long time, or else have a tremendous peak. Jones will generate discussion based on his extraordinary fielding during his peak, and those 434 dingers will help, but he ultimately falls below the threshold.

Comments powered by CComment