Exemplifying that tacit acknowledgement is the fact that when MLB integrated in 1947, none of the sixteen MLB teams were located in the Deep South; all were concentrated in the northeast quadrant of the United States. However, there was a "gentleman's agreement" against hiring black players among the team owners that was tacitly shared by Kenesaw Mountain Landis, whose tenure as MLB's commissioner lasted from 1920 to 1944, coinciding with the most of the existence of the now-recognized Negro Leagues.

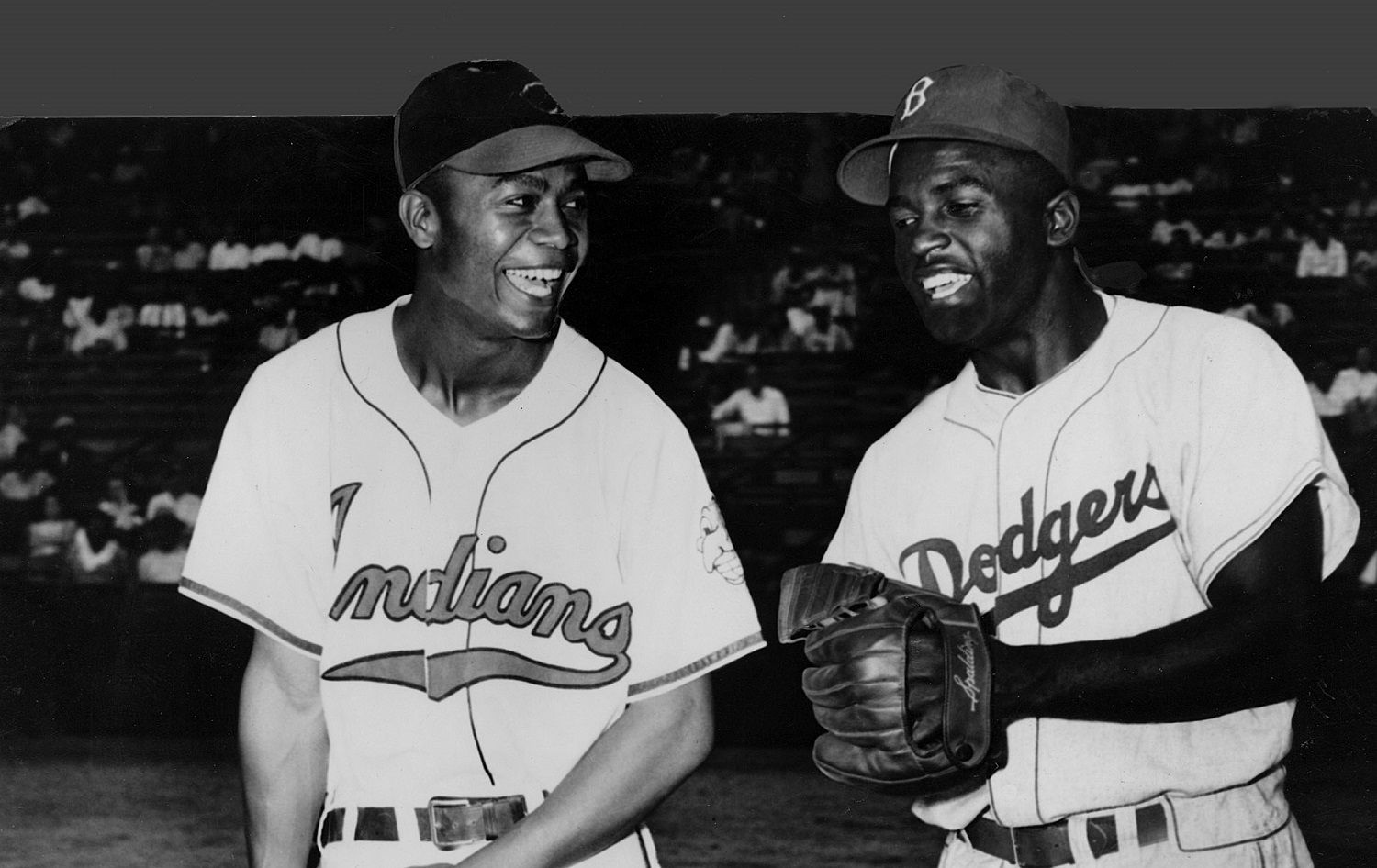

Needless to say, all were white men. But when Landis died in 1944, his replacement as MLB commissioner was Albert "Happy" Chandler, a white man who was not opposed to integration; that indeed occurred during his tenure, which lasted from 1945 to 1951. The tremendous abuse that Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to play in the National League in the 20th century in April 1947, and Larry Doby, the first to play in the American League nearly three months later, endured to participate in the "Major Leagues" was a harrowing, ugly ordeal that cannot and should not be forgotten.

Integration at last: Larry Doby (left) and Jackie Robinson, the first African-Americans of the 20th century to play, respectively, in the American and National Leagues after playing in the Negro Leagues.

Whitewashing the History of Jim Crow

But let us not forget that that abuse did not abate after their first season. De-segregating baseball was a gradual, even grudging process (the Boston Red Sox did not hire its first black player until 1959—three years after Robinson had retired), and animus against African-American players persisted and even crested by the early 1970s as Hank Aaron, closing in on Babe Ruth's career home run record, received death threats for the effrontery of being a black man about to break the record of a white man.

Again, let us not forget that the "Major Leagues" were segregated until 1947, forcing black ballplayers to create a clearly separate, conspicuously unequal major-league system because they were not permitted to play in the actual "Major Leagues." MLB's co-opting of the Negro Leagues is a wholesale attempt to sanitize the history of the era by pretending that the omission of their inclusion is simply administrative oversight. There is no other way to put this: It is a literal whitewashing of history that effaces the reality of racial segregation in the United States.

Even after the end of segregation in baseball begun in 1947, Major League Baseball remained resistant to that history or has tried to soft-pedal it. In 1969, MLB under commissioner Bowie Kuhn officially recognized six leagues, including the current American and National Leagues, as constituting the "Major Leagues" but did not include any of the Negro Leagues among them—the "oversight" that Rob Manfred had referred to above.

In 2010, the National Baseball Hall of Fame reorganized its Veterans Committee into three subcommittees, with one, covering the period from 1871 to 1946, dubbed the "Pre-Integration Era," a euphemism for "Segregation Era." (That reconfiguration was changed in 2016, with that "pre-integration" period now simply called "Early Baseball"; by 2022, another revamping resulted in the "Classic Baseball Era," now extended to 1979.)

As for the four other "major leagues" admitted in 1969, they comprised all white players, with three of them, including the American Association (1882–1891), disbanding prior to the 20th century, and two of them, the Union Association (1884) and the Players' League (1890), lasting for just one season. The Federal League lasted two seasons, 1914 and 1915. When the American Association disbanded, several of its teams were folded into the National League, while players from the other three leagues found jobs in the NL and, by the time of the Federal League, the American League as well.

But while white players could choose to throw in their lot with rival leagues and return to the NL (or, later, the AL) without penalty, black players had no choice—they had to play "separate but equal" baseball in leagues they formed themselves because they were not permitted to play in any "major league" as defined by the 1969 announcement.

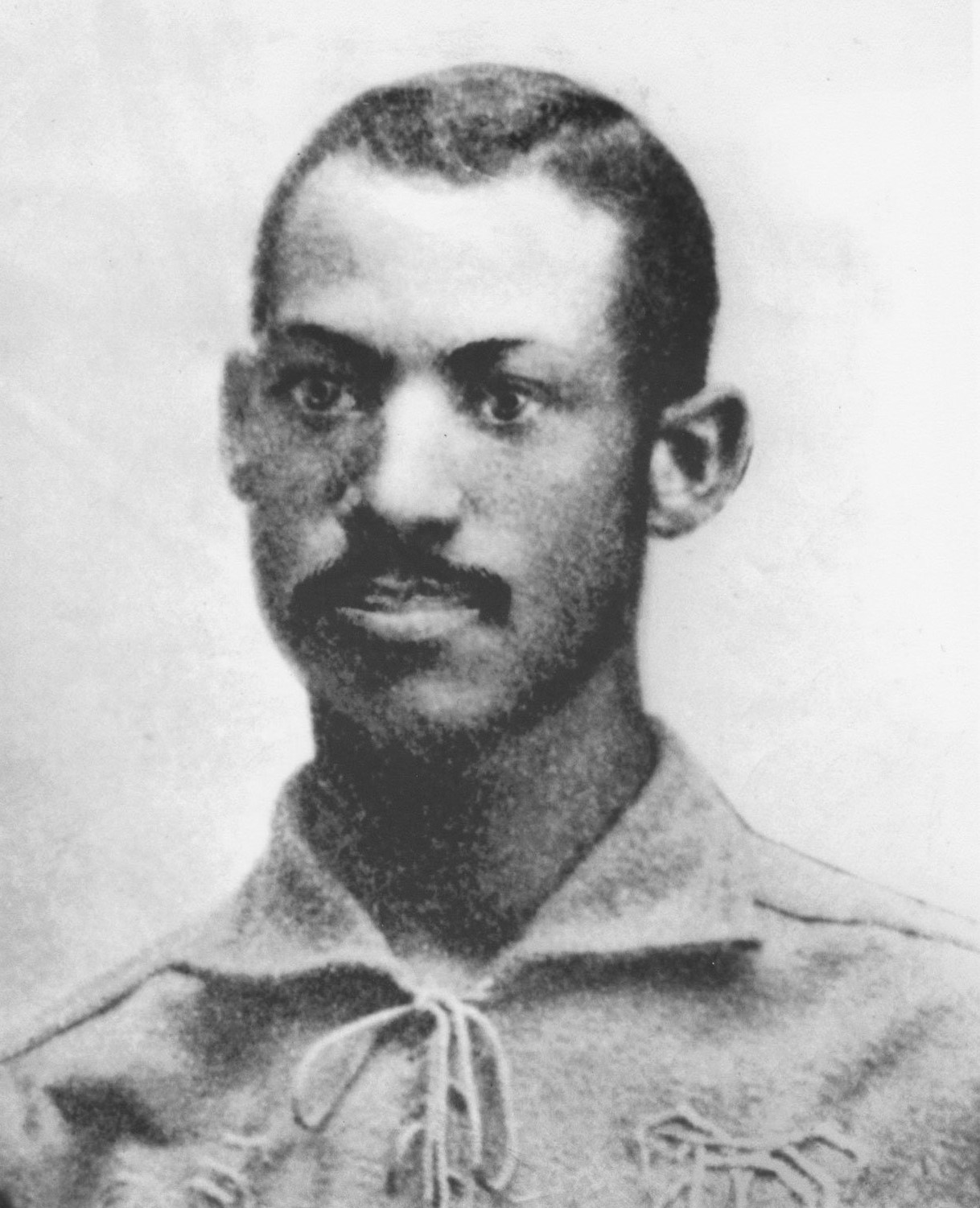

The only notable exception is Moses "Fleet" Walker, generally considered be the first clearly African-American baseball player when he played 42 games for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association in 1884. Like Doby and Robinson, Walker endured sustained abuse (notably from Hall of Famer Cap Anson) as did his brother Weldy, who played five games for the Blue Stockings in 1884. (The Walkers are predated by one William Edward White, the son of a white plantation owner and one of his black female slaves, who played one game for the Providence Grays of the National League in 1879; however, White passed as white and identified himself as such without the racial abuse the Walkers experienced.)

Moses "Fleet" Walker, the first African-American to endure racial abuse for playing Major League baseball in the 19th Century.

This is the salient fact of how Jim Crow affected baseball, and no after-the-fact assimilation of the Negro Leagues into the "Major Leagues" can change that history.

Co-opting Perceptions of History

However, that assimilation can change perceptions of that history, particularly as, overall, Americans' grasp of history is tenuous and fragmentary at best. The timing of the announcement, made at the end of 2020, raises questions about a possible ulterior motive to smooth over baseball's role in a shameful past by co-opting it through this formal recognition of the Negro Leagues.

That year, with the COVID-19 pandemic gone global and a bitterly divisive presidential election in the United States, was undoubtedly a tumultuous one. Exemplifying this was the death on May 25 of an African-American man, George Floyd, at the hands (and knees) of Minneapolis, Minnesota, police officers, which sparked protests, resistance led primarily by Black Lives Matter, and crackdowns by law enforcement and counter-resistance by white supremacists not only in the United States but also around the world.

Then, on August 26, following the shooting the previous day of another African-American man, Jacob Blake, by Kenosha, Wisconsin, police officers, which also spurred rioting and backlash, a number of American professional sports teams refused to play their games in protest. Those included six Major League Baseball teams, causing the postponement of three games, with sports strikes continuing for a couple of days afterward.

The fact that MLB teams participated in these strikes is significant in two respects. The first is that black representation in MLB is less than eight percent, yet some teams acted collectively in protest, and teams even held subsequent discussions concerning race relations not just in the sport but in the society that supports it.

The second is that among the "Big Four" big leagues of professional team sports—baseball, basketball, football, and hockey—in the United States and Canada, MLB is the most apolitical, and when it does express a political view, it is overwhelmingly conservative, in both ideology and degree of candor, whether expressed by ownership, management, or the players.

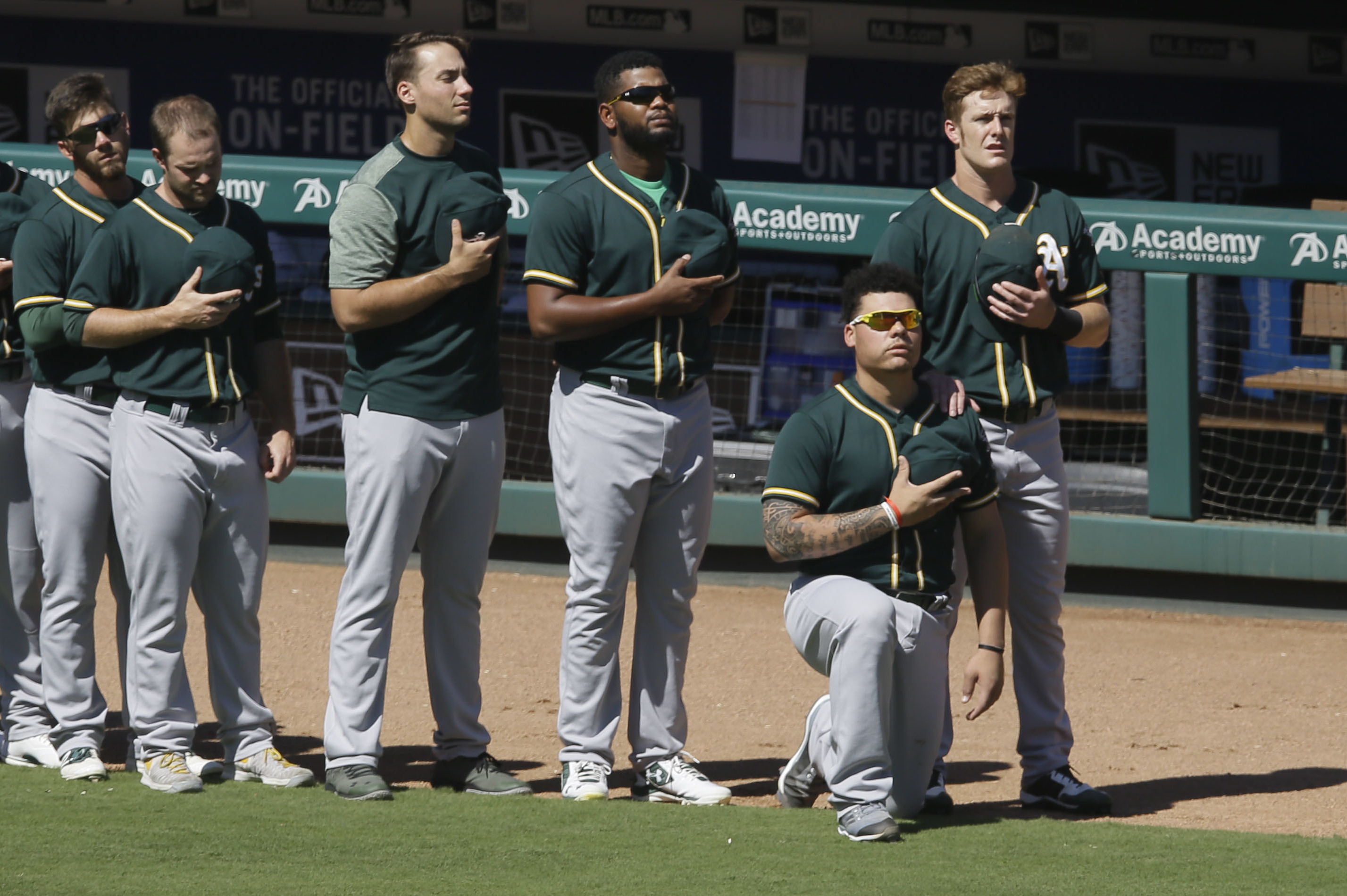

Bruce Maxwell was an exception. In September 2017, the bi-racial backup catcher for the Oakland Athletics "took the knee"—knelt in protest of racial injustice during the national anthem—and became the only Major League player to do so until 2020. He paid a price for his actions, becoming—predictably—the target of hate speech and death threats.

Although the Athletics initially supported him, MLB did not comment on his gesture. A month later, Maxwell was arrested on a felony charge of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, perhaps a consequence of his growing depression over his action and the reaction to it; he was sentenced to two years' probation in 2018. Playing in just 18 games with 58 plate appearances in 2018, Maxwell was designated for assignment in September. To date, it was his last MLB season; he currently plays in a Mexican league.

Bruce Maxwell (kneeling) was the first--and-only--Major League Baseball player to "take the knee" as a protest against racism in 2017. Six MLB teams refused to play in protest to racial violence in 2020.

Whether Bruce Maxwell's lone protest in 2017 prompted, consciously or not, a larger protest among MLB players remains to be seen. However, some Major Leaguers were stirred to more than just a token protest in 2020, and this time MLB did react with an official tweet to the George Floyd killing in June 2020 condemning racism and racial injustice.

But it's the MLB announcement made in December 2020 regarding the Negro Leagues that begs further scrutiny. As the election season drew to its contentious close in November, voters heard increasingly more about "critical race theory" (CRT), a cross-disciplinary examination of race, society, and law, as right-wing media trumpeted CRT as a prime example of "woke-ism" and "cancel culture" threatening white history and culture.

President Donald Trump seized on CRT as a campaign theme to rile up his base of supporters, launching a wave that raced down-ticket and into the state level, with several states introducing bills that circumscribed how race was to be taught in K-12 schools in 2021. (Ironically, CRT was taught in colleges and universities, not in primary or secondary education.)

Major League Baseball, despite the permanent retirement of Jackie Robinson's uniform number 42 across both leagues in 1997, has rested on its laurels about breaking the color line fifty years previously for far too long—and perhaps it knew it. So, come the end of 2020, MLB's claim that "the Negro Leagues are the Major Leagues" co-opted the race question and blended it into a sanitized narrative.

This isn't to say that the declaration is just a cynical public relations ploy. MLB might sincerely believe that the move is a genuine attempt at recognizing, understanding, and reconciling the problem. Baseball Reference certainly thinks so, having updated its invaluable data repository with Negro Leagues statistics—as it has done for other officially-recognized major leagues—and has integrated them with those players who had played subsequently in the American or National Leagues. (Baseball Reference is not affiliated with MLB.)

Controlling the Narrative to Minimize the Past

But MLB's actions are more than an official acknowledgement of an "oversight" that resulted from Jim Crow. Their tacit overlooking of Jim Crow attempts to gloss over that history by offering the hollow reparations of parity with all the other officially recognized major leagues.

The problem, however, is that the Negro Leagues were fundamentally different from all the other major leagues. They did not come into being out of choice; they came into being out of necessity.

Granted, two of the early leagues, the Federal League and the Players' League, were formed in opposition to the draconian Reserve Clause, the contractual stipulation declaring that a team controlled a player in perpetuity; meanwhile, the American Association, with "river city" teams that included the future Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates, and St. Louis Cardinals franchises, evinced a class-consciousness of sorts as "river cities" were considered socially inferior by eastern elites. By contrast, the Union Association, whose status as a "major league" has been disputed by Bill James and other baseball analysts, does indeed appear to have been a vanity league founded by St. Louis millionaire Henry Lucas.

And although the white players in these leagues left the National League (or, for the Federal League, the American League as well) to form their rival leagues, they could return to the AL or NL after their rival league had folded. Not so for African-American players—they were barred from all major leagues in any circumstance and had to create their own leagues.

This might not be a problem if issues of racism and white supremacy that dominated American society a century ago did not exist today. But they do. A hundred years later and we are still mired in that toxic, sometimes violent divisiveness. More to the point, the same attempts to whitewash history have happened recently, and continue to happen, in much more serious situations.

In 2013, the right-wing majority on the US Supreme Court struck down portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in its Shelby County v. Holder ruling, claiming that since conditions at the time of the Act's passage no longer existed, they were unconstitutional; the Act was further weakened in 2021 by the right-wing now-supermajority in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. Both decisions exemplify the extraordinary effort the right wing, acutely aware that it could never win over a majority of voters, has made to rig elections and suppress voters' ability to cast ballots, particularly votes by African-Americans.

Major League Baseball has hardly gone that far, and may very well have acted with all good intentions, but its need to control the historical narrative, wittingly or not, accomplishes a similar purpose of minimizing—if not outright effacing—the past, the Jim Crow reality of African-American baseball prior to integration, while claiming that the present is much better now that the Negro Leagues are the Major Leagues. They are not. They were the only alternative to the Major Leagues that blacks had since they were barred from playing in the Majors. Without that prohibition, there would be no Negro Leagues.

At the risk of hyperbole, because any invocation of the Holocaust is like tossing an A-bomb into a foxhole, the watchwords for that horrific tragedy are "never forget." Similarly, though, we must not forget the reality of "separate but equal" that governed Major League Baseball until 1947. That was the only reason the Negro Leagues existed, and, indeed, once Negro League players began to play in the American and National Leagues, the Negro Leagues themselves dissolved very quickly except for a few teams that continued on for exhibition and entertainment purposes.

Of course African-American players, starting with the transitional players from the Negro Leagues—Robinson and Doby along with Roy Campanella, Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, and a few others—thrived and excelled in the Major Leagues, and that is to be celebrated. And of course it is a shame that older Negro Leagues players—Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Satchel Paige (in his younger incarnation), Bullet Rogan, and many more—never got to play in the Majors, and that is to be mourned.

But the reason why they couldn't play, prohibition enforced by a systemic policy of segregation not just in Major League Baseball but in American society, must never be forgotten. And a cheap accounting trick—"hey, the Negro Leagues really were the Major Leagues all along!"—only whitewashes the reason why they were excluded. It creates a dangerous delusion that not only are things better now, but things weren't really that bad way back then. They were. Never forget.

Comments powered by CComment