Index

The Virtue of Selfishness

Movies discussed in this section, listed here alphabetically although discussed chronologically below:

![]()

![]() Atlas Shrugged, Part I (2011)

Atlas Shrugged, Part I (2011)

![]()

![]() Atlas Shrugged, Part II: The Strike (2012)

Atlas Shrugged, Part II: The Strike (2012)

![]() Atlas Shrugged, Part III: Who Is John Galt? (2014)

Atlas Shrugged, Part III: Who Is John Galt? (2014)

![]()

![]() The Fountainhead (1949)

The Fountainhead (1949)

Nearly four decades after her death, Ayn Rand has become a resurgent icon of American conservatism and libertarianism, her political and philosophical ideas, primarily Objectivism, best known through her 1957 novel Atlas Shrugged, a sprawling work that paints a dystopian United States in which intrepid industrialists, hamstrung by an interventionist, collectivist federal government, disrupt the economy by going on strike.

Rand's resurgence can be traced, at least in part, to economist Alan Greenspan, a member of Rand's inner circle in the 1950s who lauded Rand's influence when he became chairman of the Federal Reserve System, the central bank of the United States, in 1987, a position he held for nearly two decades with a firm commitment to laissez-faire capitalism and the monetarist policies associated primarily with economist Milton Friedman, both of which remain pillars of the American political right.

Rand's ideas epitomized in Atlas Shrugged got their first notable airing in her 1943 novel The Fountainhead, which featured her prototypical rugged, individualistic man struggling to erect his monuments to individual rights and freedoms to be admired as an aesthetic ideal against the daunting tide of oppressive collectivism, and if those overtones sound overtly sexual, Rand herself adapted her novel for the film version of The Fountainhead—and even Hollywood's Production Code era can't disguise some of its more outré elements.

Rand died in 1982, ironically as a beneficiary of both Social Security and Medicare—both the debilitating tools of a collectivist government, remember—which left libertarian businessman John Aglialoro struggling to erect his cinematic monument to Rand's magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, for several years until it bore its first fruit in 2011.

![]()

![]() The Fountainhead (1949)

The Fountainhead (1949)

Directed by King Vidor. Written by Ayn Rand, adapted from her eponymous novel.

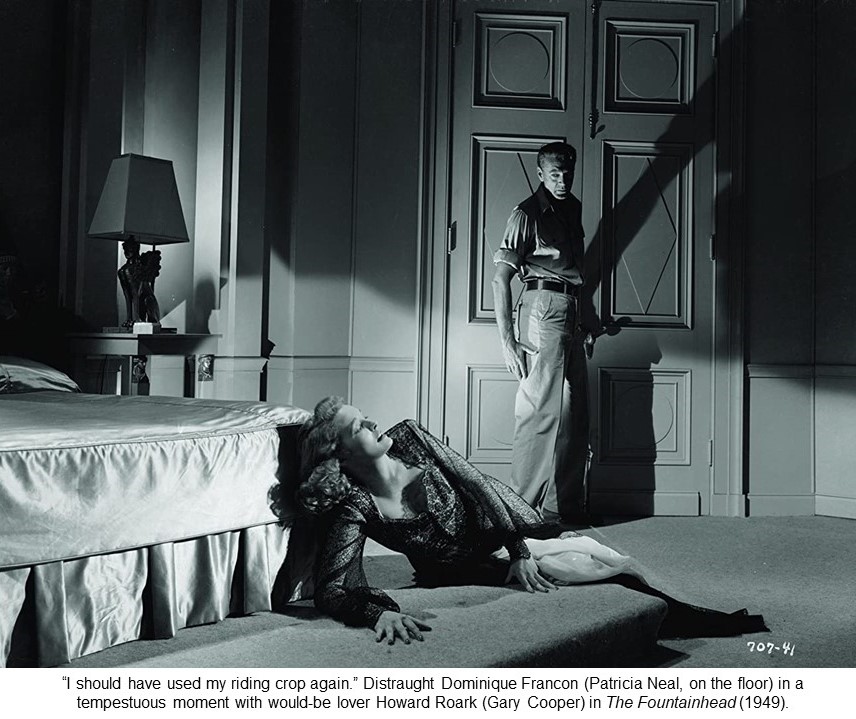

Resolute and uncompromising, steely-eyed architect Howard Roark (Gary Cooper) would rather starve than be forced to alter his conceptions, epitomizing the struggle of the visionary individual against conformist society in Rand's strident, portentous critique of collectivist oppression that's as subtle as a jackhammer.

A wealthy young dilettante (Patricia Neal), who writes a column for tabloid mogul Gail Wynand (Raymond Massey), does become Roark's champion sight unseen, although when she does meet him, working in her daddy's Connecticut quarry, she ends up striking him across his cheek with her riding crop, spurring him to ravish her later. Her name? Dominique. Really. Thus, sneering social critic Rand becomes a panting schoolgirl gushing sadomasochistic fantasy, with anguished Dominique marrying Wynand, who eventually champions Roark too, erecting Rand's modernist, ideological ménage à trois.

Vidor's perceptive direction also picks up on Rand's psychosexual cues disguised as architectural angst: Robert Burks's acute black-and-white cinematography takes in every phallic skyscraper in New York's background, climaxing with the iconic shot of an orgiastic Neal in an outdoor elevator rushing up to Cooper, astride the world's tallest skyscraper. In case you don't get what a Fountainhead really is. Cooper is, er, stiff and stilted—check his courtroom speech near the climax—but Neal, sensing Max Steiner's pervasive, melodramatic score, plays up Rand's aloof dominatrix-cum-submissive with sexy gusto, almost redeeming the leaden manifesto The Fountainhead.

![]()

![]() Atlas Shrugged, Part I (2011)

Atlas Shrugged, Part I (2011)

Directed by Paul Johansson. Written by John Aglialoro and Brian Patrick O'Toole, adapted from the eponymous novel by Ayn Rand.

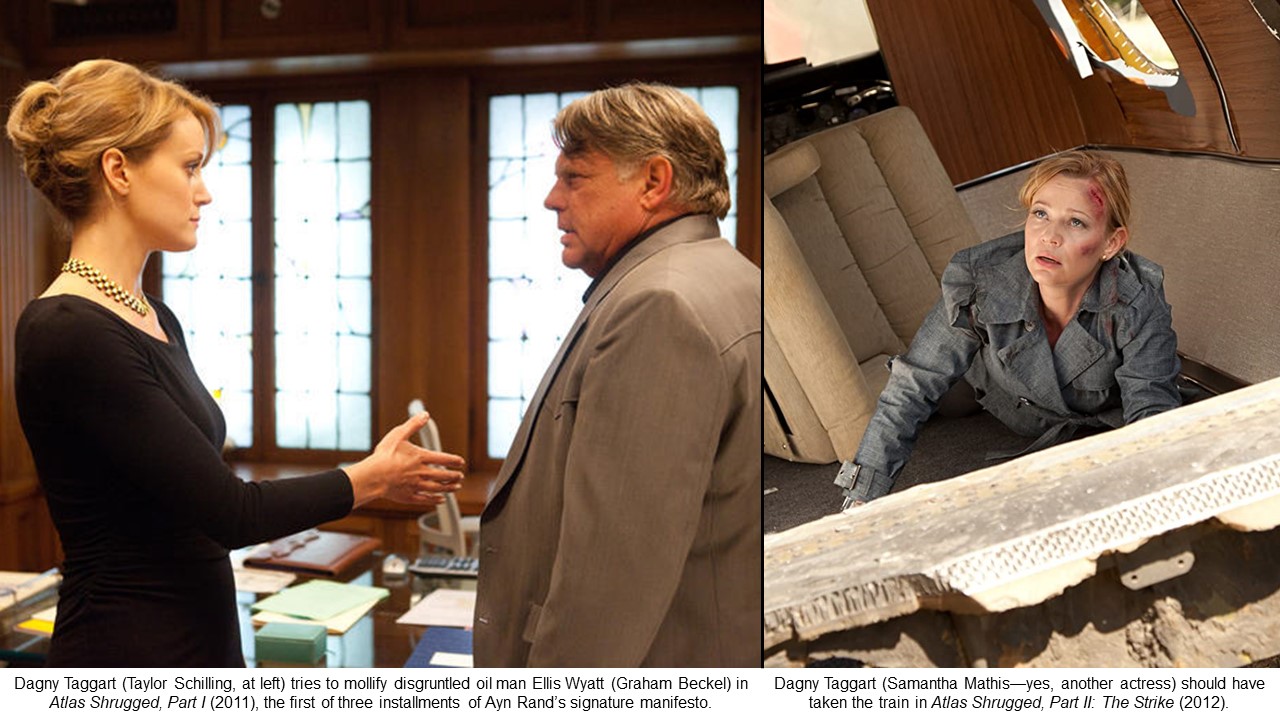

The Atlas Shrugged trilogy's most distinguishing quality is that each part features an almost entirely different cast and crew, with producer Aglialoro the only constant. Remarkably, this seeming discontinuity doesn't hamper any of the movies because all of them struggle to rise to cinematic mediocrity, and the eternal hope is that one of the teams might actually succeed through, ahem, collectivist action. Part I labors to bring together Rand's elements of mystery, romance, and social commentary on an epic scale, but its execution falls far short of its ambition. In 2016, America is wracked by depression and oil shortages that has left railroad travel as the most viable transportation option, faithfully retaining Rand's original vision but introducing the jarring juxtaposition of mid-20th-century affectation with near-future sleekness.

Trying to save Taggart Transcontinental rail lines, Dagny Taggart (Taylor Schilling) battles her scheming brother James (Matthew Marsden) and meddling bureaucrats while finding allies in maverick oilman Ellis Wyatt (Graham Beckel) and especially workaholic Hank Rearden (Grant Bowler), whose innovative metal inspires Dagny to rebuild a failing Taggart rail segment as her own company. Soon, Dagny and Hank are investigating rumors of a revolutionary motor, and the romance—well, you can see that one coming a mile away, which exemplifies the narrative deficiencies: Every line is exposition, not conversation, prompting the actors to portray their characters as symbols, not individuals. John Mott's sumptuous—if incongruous—production design and Ross Berryman's sometimes-sweeping photography cannot lift Atlas Shrugged beyond half-inspired amateurism, exemplified by Elia Cmiral's cliché-laden score. Only the partisan politics survive this aesthetic train wreck.

![]()

![]() Atlas Shrugged, Part II: The Strike (2012)

Atlas Shrugged, Part II: The Strike (2012)

Directed by John Putch. Written by Brian Patrick O'Toole, Duke Sandefur, and Duncan Scott, adapted from the eponymous novel by Ayn Rand.

The best of the Atlas Shrugged trilogy, Part II: The Strike avoids the first movie's self-conscious homage and even injects an occasional drop of humor, but while it rises to made-for-cable technical competence, this installment of Rand's saga disgorges the pat dialogue and pacing of any message-of-the-week movie without evincing any sense of grandeur. The Taggart railway-tycoon siblings, Dagny and James, are now played by, respectively, Samantha Mathis and Patrick Fabian with marginal improvement over their predecessors, although Mathis, whose Dagny is the linchpin to the Atlas Shrugged saga, is merely adequate but no more.

James has been conciliatory to big government, which continues to crack down on business, first with its "Fair Share" law, which snares Dagny's confederate and lover Hank Reardon (Jason Beghe), and then by declaring "economic martial law" with "Directive 10-289," which further forces Reardon's hand while Dagny quits her position, but a train disaster forces her back—and to a fateful encounter that heralds the third part. Part II delivers a more cohesive near-future feel along with the economic and social unrest (ostensibly inspired by the Occupy Wall Street movement), but although the dialogue is conversational and not simply polemic, it displays the banality of a prime-time soap opera even if enough vaguely familiar faces (Diedrich Bader, Paul McCrane, Thomas F. Wilson, Ray Wise) warrant pursuit of the answer to the persistent question, "Who is John Galt?"

![]() Atlas Shrugged, Part III: Who Is John Galt? (2014)

Atlas Shrugged, Part III: Who Is John Galt? (2014)

Directed by James Manera. Written by Manera, John Aglialoro, and Harmon Kaslow, adapted from the eponymous novel by Ayn Rand.

Unfortunately, the crumb of hope offered by the previous installment of producer Aglialoro's mash note to Rand and her magnum opus novel, which relates how interventionist government oppresses enterprising industrialists, comes to a shuddering close in Part III: Who Is John Galt? with all the grace and subtlety of a high-speed train derailment.

Having survived the plane crash that ended Part II, railroad magnate Dagny Taggart (Laura Regan) is lifted from the wreckage by the titular enigma (Kristoffer Polaha), seemingly stepping from a romance-novel cover to rescue the damsel. (Remember The Fountainhead?) Galt's Shangri-La in the Rockies is where he and several "disappeared" captains of industry drink wine and pontificate about the evils of "Head of State" Thompson's (Peter Mackenzie) inevitably sinister socialistic government that is failing to halt the increasing social and economic decay barely noticeable in these (mostly) white-privilege settings. Dagny refuses to join them as she believes in the (largely hypothetical) fight against the government, and Galt discreetly decides to help her—

—Argh! Enough! The narrative is as maladroit as the ludicrous sex scene between Dagny and Galt, a risible prelude to Galt's preposterous bully-pulpit sermonizing and the torture-porn finale into which Rob Morrow wanders, seemingly looking for NUMB3RS—and Morrow, top-billed in the credits as audience bait, barely makes a blip in Part III. Manera's utter lack of competence—he fiddles over fancy shots while his impoverished story crashes and burns—makes Part III: Who Is John Galt? an embarrassingly awful film, one that even cameos from fellow travelers Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, and Ron Paul cannot redeem. Who is John Galt? Who cares?

Laws and Sausages

Movies discussed in this section, listed alphabetically here although discussed chronologically below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Advise & Consent (1962)

Advise & Consent (1962)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Great McGinty (1940)

The Great McGinty (1940)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() In the Loop (2009)

In the Loop (2009)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Milk (2008)

Milk (2008)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Selma (2014)

Selma (2014)

Laws are necessary and sausages might not be too far behind, but folk wisdom dictates that you don't want to know how either one of them is made. Better just to savor the end product. Loosely grouped together are one or two movies that deal with lawmaking directly along with the bulk that deals with politicking in various forms.

The half-dozen selections in this section, all based in the United States with one or two excursions overseas, range from local to national to international politics and across issues that include civil rights, gay rights, and foreign policy. Their common theme is an insider's look at how those issues are handled within the corridors of power from city hall to the US Senate.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

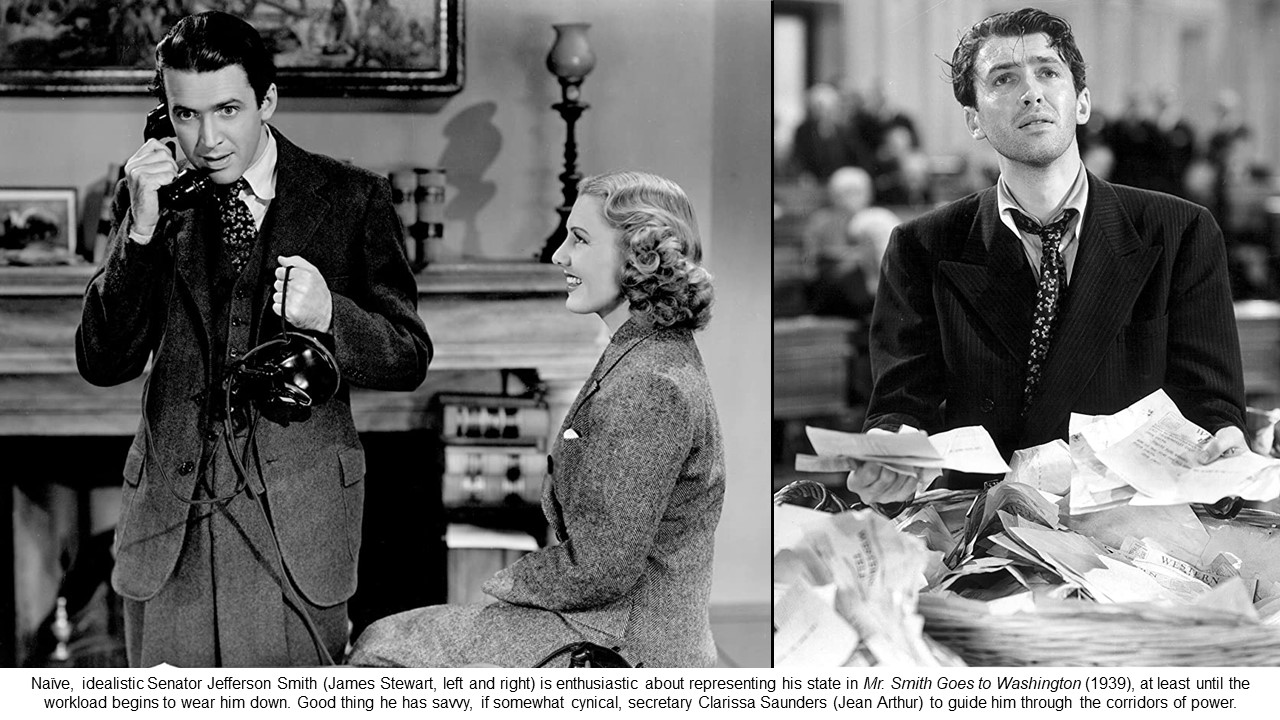

Directed by Frank Capra. Written by Sidney Buchman, adapted from the unpublished story "The Gentleman from Montana" by Lewis Foster.

Still one of the greatest films about the American political system, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is no more ashamed of its idealism as it is shy about its cynicism, and its genius is that it reconciles both attitudes without compromising either one. All right—the ending is a gyp, and Harry Carey as the President of the Senate tips his gavel hand once too often, but Capra's rousing political comedy-drama still elicits outrage and encouragement in equal measures, thanks to a star-making performance by James Stewart and an endearing one by Jean Arthur.

Stewart is Jefferson Smith, a naïve, idealistic new senator shepherded through the halls of power by Arthur's savvy, cynical secretary Clarissa Saunders—and Smith needs it as his supposed mentor, Senator Joe Paine (the always-delightful Claude Rains), will throw him under the bus to support a corrupt dam project spearheaded by powerful businessman James Taylor (Edward Arnold). To clear his name of Paine's phony charges of corruption, Smith must maintain a filibuster on the Senate floor in Mr. Smith's iconic climax as Saunders is finally won over by Smith's idealism and Carey's senate president tips the audience reaction.

Marshaling his performers while quietly driving the narrative, Capra emphasizes the small gesture as much as the broad statement, supported by Joseph Walker's sympathetic black and white photography and Dmitri Tiomkin's discreet score, as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, heart proudly on its sleeve, wins by a landslide.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The Great McGinty (1940)

The Great McGinty (1940)

Written and directed by Preston Sturges.

Offering a political spin on the rags-to-riches-to-rags formula, Sturges, in his directorial debut, gives incisive teeth to the potent, brilliantly scripted The Great McGinty, which strikes uncomfortably close to precinct patronage while offering an ultimately endearing cautionary tale. (Check The Last Hurrah, in the Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail section, for a more sentimental contrast.) Tough guy Brian Donlevy is Dan McGinty, a once-and-future political star who winds up tending bar in an unnamed banana republic and counseling a despondent expatriate banker whose moment of weakness reminds McGinty of his own downfall.

When a low-level political fixer (William Demarest), impressed by hobo McGinty's resourcefulness in fraudulent municipal voting, brings him to his boss (the wonderfully malaprop-prone Akim Tamiroff), McGinty becomes his enforcer, and then his political protégé, becoming the "reform" mayor. Of course, to appear respectable, McGinty has to marry his secretary, single mother Catherine (Muriel Angelus), whose integrity begins to rub off on McGinty as they fall for each other—and forces him to his "moment of weakness" when the boss decides that he should be governor. In Donlevy, Sturges has the ideal spearhead for his keenly uncomfortable skewering of political machines and local corruption as The Great McGinty heralds the arrival of Sturges as a witty, perceptive, slyly satirical filmmaker and social critic.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Advise & Consent (1962)

Advise & Consent (1962)

Directed by Otto Preminger. Written by Wendell Mayes, adapted from the eponymous novel by Allen Drury.

With a forceful yank, Advise & Consent pulls back the curtain on the United States Senate to expose the public and private workings of this eminently powerful legislative body during the contentious confirmation hearings of Robert Leffingwell (Henry Fonda), the ailing President's (Franchot Tone) controversial nominee for Secretary of State, in this powerful if flawed political drama. Liberal Leffingwell's backers include Majority Leader Bob Munson (Walter Pidgeon), but the glib intellectual faces opposition from Senator Brig Anderson (Don Murray) and from reactionary Senator Seab Cooley (Charles Laughton), whose surprise witness, Herbert Gelman (Burgess Meredith), accuses Leffingwell of being a communist.

Although Leffingwell publicly refutes Gelman, he perjures himself in the process and insists that the President withdraw his nomination. The President refuses, inciting Anderson—and prompting Senator Fred Van Ackerman (George Grizzard), sympathetic to Leffingwell, to dig up explosive dirt on Anderson. (Note the parallels with The Best Man in the Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail section.) That last, along with the President's ill health, mars Advise & Consent with melodramatic contrivance for much of its second half, although the first half crackles with seamless assurance and remains a definitive portrayal of American governance, honorable and otherwise. Preminger renders Advise & Consent an unblinking portrait of power and zealousness, idealism and pragmatism, and old-fashioned political mud-wrestling.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Milk (2008)

Milk (2008)

Directed by Gus Van Sant. Written by Dustin Lance Black.

Sean Penn inhabits the title personage in Milk, the involving political biopic about Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man elected to California public office before being assassinated in 1978. Informed by the acclaimed 1984 documentary The Times of Harvey Milk, Black delivers a hard-hitting if occasionally earnest narrative although director Van Sant softens the edges with his sympathetic investment in this gritty, little-explored examination of gay rights. When Milk and his lover Scott Smith (James Franco) open a camera shop in San Francisco, the animosity they encounter prompts Milk to activism, eventually winning a seat on the city supervisors' board in 1977.

There he meets conservative supervisor Dan White (Josh Brolin), whose adversarial relationship with Milk, and, later, with Mayor George Moscone (Victor Garber), leads to Milk's climactic confrontation. Black and Van Sant use the state and national anti-gay efforts of John Briggs and Anita Bryant as both the impetus and mirror for Milk and his followers, contrasting the political battles with Milk's contentious personal life as Van Sant, working around some uneven performances, develops intimacy amidst the throng, with cinematographer Harris Savides's washed-out photography supplying period patina and Danny Elfman's score avoiding his usual annoying quirks. But Milk belongs to Penn, who transcends mimicry and stereotype to make Harvey Milk a genuine inspiration.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() In the Loop (2009)

In the Loop (2009)

Directed by Armando Iannucci. Written by Iannucci with Jesse Armstrong, Simon Blackwell, and Tony Roche.

Every edge of the political satire In the Loop is so sharp that no one can avoid getting nicked, let alone gored, by its scathing, take-no-prisoners approach that examines the petty, territorial, backstabbing, yet ultimately influential and consequential machinations of mid-level bureaucrats on both sides of the Atlantic (think The West Wing with switchblades) during the run-up to an imminent invasion of a Middle Eastern country (think 2003 invasion of Iraq).

When Secretary of State for International Development Simon Foster (Tom Hollander) publicly blunders his opinion about the possibility of a war, communications director Malcolm Tucker (a torrential Peter Capaldi) rakes him over the coals, but not before Foster attracts the interest of American Undersecretary of State Karen Clarke (Mimi Kennedy), whose aide, Liza Weld (Anna Chlumsky), has authored a paper that actually argues against an invasion but is eventually spun as the rationale to go to war.

Director Iannucci doesn't waste a frame as he whips the story to a heady froth, with the poor unfortunate who gets thrown under the bus getting it in the most banal manner possible, while In the Loop's relentless, profane sardonicism demands full attention for the full hilarious effect. The only knocks are with the barrage of cultural references in danger of becoming stale—although the details of the invasion are suitably vague enough to avoid pigeonholing—and that there isn't anyone likeable or sympathetic here, a serious omission for a film looking to excoriate everyone within sight.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Selma (2014)

Selma (2014)

Directed by Ava DuVernay. Written by Paul Webb.

Voting-rights struggles during the Civil Rights era come to a head in Selma, the Alabama city that became a flashpoint for white resistance to African-Americans' registration efforts led by Martin Luther King, Jr. (David Oyelowo), and a series of peaceful protest marches whose brutal suppression shocked the world and prompted federal legislation championed by President Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) as director DuVernay's absorbing, affecting docudrama makes those historical events sear with the immediacy of a contemporary news flash—all too contemporary in the wake of 2020's Black Lives Matter confrontations.

Webb's thoroughgoing script encompasses a historian's dream of personages and events—from Malcolm X (Nigél Thatch) to J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker) to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963 Birmingham—before sending King into 1965 Selma to support registration efforts, only to be rebuffed by city leaders ultimately supported by Alabama Governor George Wallace (Tim Roth). Meanwhile, internecine struggles between King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee also hamper the efforts as Hoover's zeal to discredit King foments alienation between King and his wife Coretta (Carmen Ejogo). (Hoover gets his own spotlight in the Presidents and Pretenders to the Throne section below.)

As waves of personal anguish highlight the iconic, horrific confrontations at Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge, Oyelowo, tasked with portraying an icon, makes King human, not symbolic, while Wilkinson, similarly challenged, delivers a yeoman performance, although final credit for Selma's triumph belongs to DuVernay's sweeping, empathetic vision.

Comments powered by CComment