The Current Structure of the Veterans Committee

Actually, since 2010 the "Veterans Committee" has comprised three separate committees: the Pre-Integration Committee, which covers the period from 1876 to 1946; the Golden Era Committee (1947–1972); and the Expansion Era Committee (1973–present). Each committee meets annually on a rotating basis to evaluate and vote on a roster of candidates selected by a Historical Overview Committee for that particular era. That roster may contain individuals who had been managers, umpires, executives (which includes team owners, general managers, and major league officials), and long-retired players, and just as with the BBWAA balloting, a candidate who receives at least 75 percent of the vote from that era's committee is thus elected to the Hall of Fame.Last year, the Expansion Era Committee chose three inductees—Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa, and Joe Torre—all managers, although Torre's record as a near-Hall of Fame player was likely another factor, and all are worthy choices. The previous year, the Pre-Integration Era Committee also chose three inductees: Hank O'Day, who, elected as an umpire, also had careers as a baseball player and manager; Jacob Ruppert, the owner of the New York Yankees responsible for bringing Babe Ruth to the franchise; and Deacon White, a Deadball-era player who retired more than a decade before the Wright Brothers flew their first successful airplane.

In 2012, the Golden Era Committee elected one player to the Hall of Fame: Ron Santo, whose initial snubbing by the BBWAA voters had been criticized for years as his case for why he should be in the Hall became stronger every year. (I too championed Santo in my very first column for this site.)

Santo's was an oversight that the Committee corrected—but are there any other players from the "Golden Era" whose careers have been unjustly overlooked?

The 2015 Golden Era Ballot

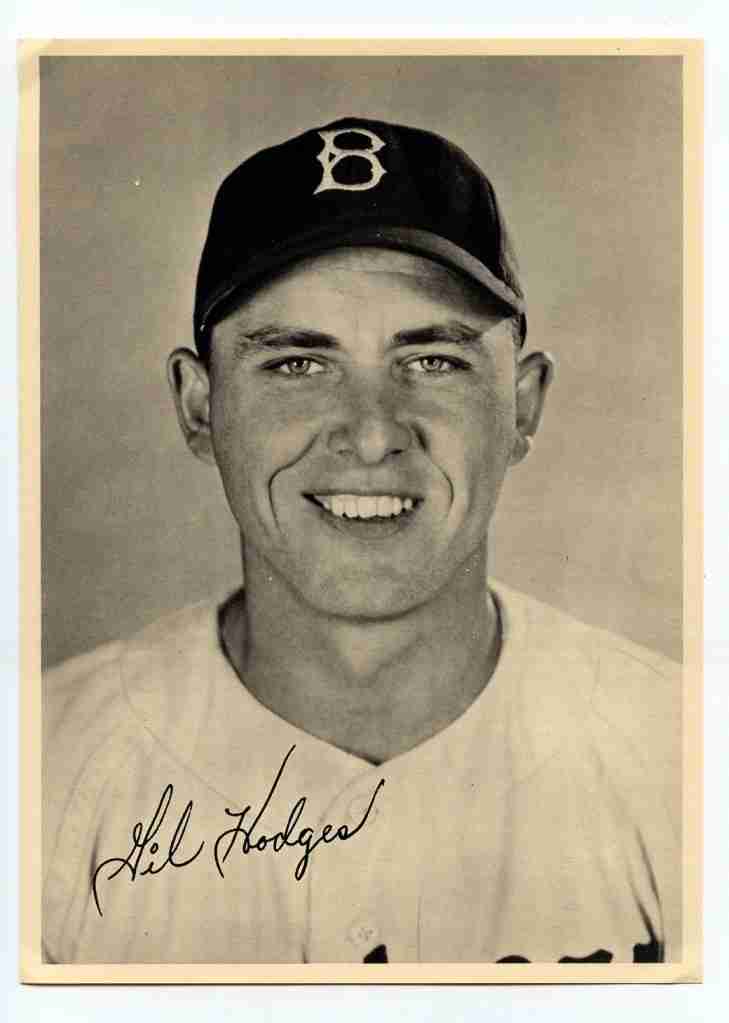

This year's Golden Era Committee has ten candidates to consider, nine players and one executive. The nine players are Dick Allen, Ken Boyer, Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso, Tony Oliva, Billy Pierce, Luis Tiant, and Maury Wills. The sole executive is Bob Howsam.Six of those players were on the 2012 ballot, with Allen, Pierce, and Wills being new for this year. Kaat was the top vote-getter in 2012, garnering 10 of the 16 possible votes for a 62.5 percent showing; Hodges and Miñoso each got nine votes (56.3 percent) while Oliva polled eight (50 percent). Boyer and Tiant received less than three votes each.

All nine players appeared on ballots voted on by BBWAA voters when they were first eligible following retirement—although the fates of three players, noted in the table below, took some interesting wrinkles.

Dick Allen was one-and-done in 1983, but he was returned to the ballot in 1985 and remained on it until 1997, which was his 15th and final year on the ballot—and it included his "missing" year of 1984, when he was not on the ballot.

Ken Boyer spent five years on the ballot beginning with his first year of eligibility in 1975, but he never received five percent of the vote during that time and was dropped following 1979. However, he re-emerged on the ballot in 1985 and remained on it for ten more years, giving him the full 15 years commonly granted (barring election or falling below the five percent threshold) until 2014, when it was announced that the maximum allowable time on the ballot will be reduced to ten years starting with the 2015 vote.

Minnie Miñoso was also a one-and-done in 1969, following his seeming retirement from Major League Baseball in 1964, but then he made brief returns to the Majors in 1976 and again in 1980—more on Miñoso's surprising longevity later—which restarted his eligibility clock, as it were, and he remained on the ballot for 14 more years starting in 1986.

The table below summarizes the nine players' experience on the BBWAA ballots, listing their first year of eligibility (including the anomalous situations described above), the number of years they were on a BBWAA ballot, the percentage of the vote they received in the first and last years of eligibility, and the highest percentage of the vote they received during their entire run on the ballot.

| 2015 Golden Era Candidates, BBWAA Voting Summary |

||||||

| Player |

First Eligible |

Years on Ballot |

Debut Percentage |

Ending Percentage |

Highest Percentage |

|

| * Allen, Dick |

1983 |

1 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

|

| * Allen, Dick |

1985 |

13 |

7.1 |

16.7 |

18.9 |

|

| ** Boyer, Ken |

1975 |

5 |

2.5 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

|

| ** Boyer, Ken |

1985 |

10 |

17.2 |

11.8 |

25.5 |

|

| Hodges, Gil |

1969 |

15 |

24.1 |

63.4 |

63.4 |

|

| Kaat, Jim |

1989 |

15 |

19.5 |

26.2 |

29.6 |

|

| *** Miñoso, Minnie |

1969 |

1 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

| *** Miñoso, Minnie |

1986 |

14 |

20.9 |

14.7 |

21.1 |

|

| Oliva, Tony |

1982 |

15 |

15.2 |

36.2 |

47.3 |

|

| Pierce, Billy |

1970 |

5 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

|

| Tiant, Luis |

1988 |

15 |

30.9 |

18.0 |

30.9 |

|

| Wills, Maury |

1978 |

15 |

30.3 |

25.6 |

40.6 |

|

** Ken Boyer did not meet the five percent of the vote on his first ballot in 1975, but he remained on the ballot until 1979. However, he was reinstated to the BBWAA ballot in 1985.

*** Minnie Miñoso did not meet the five percent of the vote on his first BBWAA ballot in 1969, which followed his last year in the majors in 1964, and he was dropped from subsequent ballots. However, Miñoso returned to the majors briefly in 1976 and in 1980, which reactivated his eligibility starting in 1986.

Seven of the nine Golden Era player-candidates had been on the BBWAA ballot for the full 15 years then established as the maximum number of years allowed on the writers' ballot; Dick Allen was on the ballot for 14 years all told, having lost a year of eligibility between his first year of eligibility and his reinstatement two years later, and Billy Pierce was on the ballot for only five years even though he never reached the two-percent mark in voting during that time. Gil Hodges had the best showing, netting 63.4 percent of the vote in his final year of 1983, which is significant because no other candidate even reached the 50-percent mark in voting during his time on the writers' ballot.

In other words, BBWAA voters of the time did not consider any of the 2015 Golden Era player-candidates to be Hall of Fame-caliber players when each had the opportunity to be voted in by the writers. They did ask for Ken Boyer to be reinstated after his first stint, and his ballot performance was much better during his second term although his best showing was about 25 percent; significantly, though, Ron Santo was also a reinstatement at this time, and the Golden Era Committee did elect Santo to the Hall in 2012. Dick Allen, too, got a new lease of life although he never reached the 19-percent mark in any year on the ballot.

So, are any of the nine players on the 2015 Golden Era ballot secretly Hall of Famers just waiting to be recognized? Will today's advanced statistical analysis help to reveal that fact? That is our purpose here, but before we begin to analyze the players and speculate upon their fate, let's look at the current Golden Era Committee and at a brief history of the Veterans Committee.

The 2015 Golden Era Committee

The 2015 Golden Era Committee comprises 16 members, eight who are currently enshrined in the Hall of Fame (seven players and one executive), four executives, and four media figures. The committee composition differs significantly from the 2012 committee that elected Ron Santo to the Hall; only four members of the 2012 committee are on this current committee.The Hall of Fame members of the current committee are Jim Bunning, Rod Carew, Pat Gillick, Ferguson Jenkins, Al Kaline, Joe Morgan, Ozzie Smith, and Don Sutton. Only Gillick was not a player, and he and Bunning were elected by the Veterans Committee. The executives are Jim Frey, David Glass, Roland Hemond, and Bob Watson. Watson is a former general manager, notably with the New York Yankees, with whom he won the 1996 World Series and became the first African-American GM to win a world championship, and was also a Major League Baseball official as vice president in charge of discipline and vice president of rules and on-field operations until he retired in 2010; Watson was also a former player with a respectable 19-year career primarily with the Houston Astros, with whom he was thought to have scored MLB's one millionth run in 1975, although that has been disputed subsequently. The media members of the committee are Steve Hirdt, Dick Kaegel, Phil Pepe, and Tracy Ringoldsby.

Kaline, Sutton, Hemond, and Kaegel were members of the 2012 committee.

Brief History of the Veterans Committee

Before evaluating the ten candidates for the 2015 Golden Era ballot, it is useful to review a brief history of the post-BBWAA Hall of Fame voting that has been the task of baseball's various Veterans Committees since 1939. That action in 1939, by the Old Timers Committee, came just three years after the very first elections by the BBWAA in 1936 with the intention of recognizing 19th-century players, including Cap Anson, Candy Cummings, Buck Ewing, and Old Hoss Radbourn.It indicated early on that baseball was keenly invested in its legacy, and in ensuring that a mechanism existed to memorialize players who may have escaped the notice of the writers; it also ensured that non-players integral to the history of the game also got proper recognition, which in fact began in 1937 with the induction of executives, pioneers, and managers (specifically, Connie Mack and John McGraw). This attention to the game's legacy continued to be felt as, beginning in 1971, a separate Negro Leagues Committee began inducting players (for example, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Buck Leonard) and non-players (Rube Foster) whose careers were primarily or exclusively in the Negro Leagues prior to baseball's integration in 1947.

Since then the various and sundry committees have been criticized either for inducting too many players, or else players of lesser caliber, or not inducting anyone. Adding to the confusion and criticism are the various names of committees tasked with specific duties, and the rules and mandates committees labored under, which over the years have changed as often as have the names of the committees.

For example, in 1945 the Old Timers Committee selected ten inductees as had been requested by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who had died in late 1944 and was himself almost immediately inducted into the Hall; in addition, his mandate lived on as the Old Timers Committee did indeed induct ten players whose careers were primarily in the 19th century, including Dan Brouthers, Jimmy Collins, and King Kelly. This was done also to break up the logjam on the BBWAA ballot, as the BBWAA, which had been meeting every three years at this time, had not elected anyone in 1945. (And does a "logjam" sound similar to our current situation with the BBWAA ballot?)

And even though the Committee was later criticized for inducting too many players, it returned the following year to select eleven more players, including Jesse Burkett, Eddie Plank, and the Cubs' famed double-play team of Frank Chance, Johnny Evers, and Joe Tinker. And while Burkett and 325-game winner Plank seemed reasonable, the Cubs' trio has since been regarded as a sentimental rather than a substantive vote. Moreover, even though the 1945 vote drew criticism only retrospectively, the 1946 vote drew complaints almost immediately, not only for the Committee's choices (right fielder Tommy McCarthy, chosen in 1946, is often regarded as the worst player in the Hall of Fame; his Wins Above Replacement, from baseball-reference.com, admittedly a retrospective value, is 16.1—with the average value of all 24 right fielders in the Hall being 73.2), but for infringing on the responsibilities of the BBWAA, which had been unable to elect candidates at this time.

Thus the Committee scaled back its scope and operations, waiting until 1949 to elect only two players (pitchers Mordecai Brown and Kid Nichols), then waiting four years to elect six candidates (only two of whom were players), and then electing just two candidates every other year until 1961. By now the Committee had renamed and reconstituted itself as the Committee on Baseball Veterans, shortened as the Veterans Committee, and that name has stuck as the catch-all term for any non-BBWAA body evaluating potential Hall of Famers even if the name itself is not actually in use.

In 1962, the Committee (and we are using the catch-all term for simplicity's sake) resumed annual operations, and it remained that way until the end of the century, although names, scope, and members have changed significantly over the last half-century; for instance, the Committee began evaluating Negro Leagues personages for the Hall.

Not that the Committee then became immune to criticism. In the early 1970s, the Committee, with Hall of Fame players Frankie Frisch and Bill Terry prominent members, selected several players, including Chick Hafey, Jesse Haines, High Pockets Kelly, and Rube Marquard, whose credentials are hardly up to Hall standards—more suspiciously, they were also one-time teammates of either Frisch's or Terry's. Thus the Committee's reputation took a serious hit. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the Committee elected no one in 1988, 1990, and 1993.

But even following the suspected Frisch-Terry collusion, the Committee still elected players whose credentials did not seem substantial enough for the Hall of Fame. For every Johnny Mize or Ron Santo or Hoyt Wilhelm elected by the Committee, players whose records and impact were overlooked by the BBWAA, there are a host of marginal players whom the Committee has also deemed worthy of the Hall, including George Kell, Chuck Klein, Bill Mazeroski, Phil Rizzuto, and Hack Wilson.

By the turn of this century, the Veterans Committee instituted a radical reform, greatly expanding the pool of members, including all living Hall of Famers, and creating a Historical Overview Committee to nominate 260 candidates, including 200 players and 60 managers, umpires, and executives. Such an ambitious undertaking resulted, not surprisingly perhaps, in no elections of former players—although the top three vote-getters were Gil Hodges, Tony Oliva, and Ron Santo. In 2005, the Historical Overview Committee offered voters a much-trimmed ballot of 25 players, although voters were still unable to deliver at least 75 percent of the vote required for election to any candidate; again, though, Hodges, Oliva, and Santo were the three highest vote-getters, with first-timer Jim Kaat close behind. The results were the same in 2007—three shutouts in a row—and criticism of the Committee's methods and standards was becoming widespread.

Thus the Committee tried again in 2007, splitting the composite ballot of all candidates into two separate ballots for non-players, one for managers and umpires and one for executives, while reducing the voting membership to a handful of Hall of Famers and adding a small contingent of executives and media members. The Committee would also vote on the non-player ballots only in even-numbered years starting in 2008; meanwhile, the players ballot in 2008, which was limited to players whose careers began after 1943, did not see any elections (although the top finishers remained Santo, Kaat, Oliva, and Hodges), but a separate election in late 2008 for the Class of 2009 for those players whose careers did begin before 1943 yielded the election of second baseman Joe Gordon.

Following a final, non-players vote in late 2009 for the Class of 2010, which saw the election of umpire Doug Harvey and manager Whitey Herzog, the old Veterans Committee was sundered. It was replaced by the current configuration of three separate committees—the Pre-Integration Era (1876 to 1946) Committee, the Golden Era (1947 to 1972) Committee, and the Expansion Era (1973 to the present) Committee—that would vote in turn every year, meaning that each committee would vote every three years. The Historical Overview Committee would continue to select the candidates for each ballot, with that ballot now including players and non-players alike. And a select number of members—players, executives, and media figures—would staff each committee, with most members joining for one session before being replaced.

First up for the Class of 2011 was the Expansion Era Committee, which voted executive Pat Gillick, who as a general manager won world championships with the Toronto Blue Jays (1992, 1993) and Philadelphia Phillies (2008), into the Hall. The Golden Era Committee voted Ron Santo into the Hall for 2012. In 2013, the Pre-Integration Committee elected three candidates, umpire Hank O'Day, executive Jacob Ruppert, and catcher/third baseman Deacon White, in a year that saw the BBWAA unable to muster a 75-percent vote for any player on its superstar-packed ballot that was also laced by players with known or suspected performance-enhancing drug involvement (this was the first ballot for left fielder Barry Bonds and pitcher Roger Clemens, for instance)—leading to sardonic remarks about how the only Hall-worthy candidates in 2013 were those who had been dead for more than seven decades. The Expansion Era Committee, in its second showing for the Class of 2014, did manage to elect three managers, Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa, and Joe Torre, who are all living; they joined the three candidates the BBWAA managed to elect for 2014, pitcher Tom Glavine, pitcher Greg Maddux, and first baseman/designated hitter Frank Thomas, at Cooperstown, New York, for the induction ceremonies earlier this year.

Which brings us to the Golden Era Committee's turn at bat for the Class of 2015. But although the changes instituted from 2011 on seem to be viable, a vital question remains unanswered: Are there really any Hall of Fame players left unselected from the Pre-Integration and Golden Eras?

Of course, cases can still be made for a few players from the Pre-Integration Era (I would make one for shortstop Bill Dahlen), and we will soon find out whether any of the player-candidates for the 2015 Golden Era Committee ballot are truly Hall of Fame-caliber. But the point is this: After three-quarters of a century of baseball second-guessing itself—or at least the Baseball Writers Association of America—about the legacy of its players and non-players alike, haven't these candidates been examined and re-examined enough already?

A re-examination using current advanced metrics may reveal a Ron Santo or a Bill Dahlen, a "sleeper" Hall of Famer whose anecdotal tales of greatness are validated by his statistical record. (Conversely, those same metrics can reveal that existing Hall of Famers may not be as good as their tales initially advertised them to be.)

Will the Historical Overview Committee keep sending the same candidates to the ballots until it finds a voting committee that will finally elect them? Or, as with the BBWAA ballot, should there be a statute of limitations, a maximum number of times a candidate can appear on a "Veterans Committee" ballot before being removed permanently? (Keeping in mind that this year the BBWAA rules were amended to shorten the time allowed on its ballot from fifteen years to ten years.)

For our purposes, these are rhetorical questions, but they are ones to keep in mind as we examine these well-examined nine players on the 2015 Golden Era ballot.

The 2015 Golden Era Player Candidates

Make no mistake about the nine player candidates on the 2015 Golden Era ballot: They are "bubble" candidates—players whose records and accomplishments are on that great, fuzzy margin that separates Hall of Fame talent from the rest of the field.If there are any players here who truly belong in the Hall, it will be a judgment call to elect them now—keeping in mind that with two exceptions, Dick Allen and Billy Pierce, these players were on BBWAA ballots for all fifteen years of eligibility (Allen was on fourteen ballots; Pierce on five), all nine players have been considered by previous Veterans Committees, and all except for Allen, Pierce, and Maury Wills were on the 2012 Golden Era ballot that elected Ron Santo to the Hall.

The players' records don't change but perceptions of them do. In a context-neutral setting, Santo's numbers were not eye-popping, but putting him in the context of the tough-pitching 1960s and his playing for the generally hapless Chicago Cubs, along with advanced qualitative statistics that supported the anecdotal evidence of Santo's excellence, convinced committee voters in 2012. Will any candidates in 2015 experience a similar reversal of fortune?

Perhaps, but even advanced statistics may not help as much as could be expected, at least with respect to Wins Above Replacement player, or WAR, which measures a player's contribution to his team's wins, taking into account his offensive and defensive contributions, above what a replacement player would contribute. WAR is not a be-all and end-all statistic, but it does give an indication of a player's worth, and it is the only statistic that can be used to compare position players with pitchers. There are different versions of WAR; the two versions discussed here are from Baseball Reference (bWAR) and FanGraphs (fWAR). Often, the difference between the two is marginal—but as we will see below, there can be significant differences in a couple of cases.

Here are the six position players on the 2015 Golden Era ballot, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it and explained below the table.

| Position Players on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Boyer, Ken |

.287/.349/.462 |

.355 |

62.8 |

54.8 |

116 |

116 |

| Allen, Dick |

.292/.378/.534 |

.400 |

58.7 |

61.3 |

156 |

155 |

| Miñoso, Minnie |

.298/.389/.459 |

.382 |

50.1 |

50.8 |

130 |

133 |

| Hodges, Gil |

.273/.359/.487 |

.378 |

44.9 |

42.1 |

120 |

121 |

| Oliva, Tony |

.304/.353/.476 |

.365 |

43.0 |

40.7 |

131 |

129 |

| Wills, Maury |

.281/.330/.331 |

.301 |

39.5 |

35.7 |

88 |

91 |

wOBA: Weighted on-base average as calculated by FanGraphs. Weighs singles, extra-base hits, walks, and hits by pitch; generally, .400 is excellent and .320 is league-average.

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

OPS+: Career on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 OPS+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

wRC+: Career weighted Runs Created, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 wRC+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

Here are the three pitchers on the 2015 Golden Era ballot, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it and explained below the table.

| Pitchers on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Pitcher |

W-L (S), ERA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

ERA+ |

ERA– |

FIP– |

| Tiant, Luis |

229–172 (15), 3.30 |

66.7 |

53.9 |

114 |

87 |

90 |

| Pierce, Billy |

211–169 (32), 3.27 |

53.2 |

54.7 |

119 |

84 |

90 |

| Kaat, Jim |

283–237 (18), 3.45 |

45.3 |

69.4 |

108 |

93 |

90 |

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

ERA+: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA+ indicating a league-average pitcher, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

ERA–: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA- indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

FIP–: Fielding-independent pitching, a pitcher's ERA with his fielders' impact factored out, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 FIP– indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

The table below combines both position players and pitchers into a ranking by bWAR with their fWAR values also listed.

| All 2015 Golden Era Candidates, Ranked by bWAR |

|||

| Rank |

Player |

bWAR |

fWAR |

| 1 |

Tiant, Luis |

66.7 |

53.9 |

| 2 |

Boyer, Ken |

62.8 |

54.8 |

| 3 |

Allen, Dick |

58.7 |

61.3 |

| 4 |

Pierce, Billy |

53.2 |

54.7 |

| 5 |

Miñoso, Minnie |

50.1 |

50.8 |

| 6 |

Kaat, Jim |

45.3 |

69.4 |

| 7 |

Hodges, Gil |

44.9 |

42.1 |

| 8 |

Oliva, Tony |

43.0 |

40.7 |

| 9 |

Wills, Maury |

39.5 |

35.7 |

The table below combines both position players and pitchers into a ranking by fWAR with their bWAR values also listed.

| All 2015 Golden Era Candidates, Ranked by fWAR |

|||

| Rank |

Player |

fWAR |

bWAR |

| 1 |

Kaat, Jim |

69.4 |

45.3 |

| 2 |

Allen, Dick |

61.3 |

58.7 |

| 3 |

Boyer, Ken |

54.8 |

62.8 |

| 4 |

Pierce, Billy |

54.7 |

53.2 |

| 5 |

Tiant, Luis |

53.9 |

66.7 |

| 6 |

Miñoso, Minnie |

50.8 |

50.1 |

| 7 |

Hodges, Gil |

42.1 |

44.9 |

| 8 |

Oliva, Tony |

40.7 |

43.0 |

| 9 |

Wills, Maury |

35.7 |

39.5 |

Yes, there is. Sabermetrician Jay Jaffe has developed "JAWS," the Jaffe WAR Score system, to compare a player at a position against all players, in aggregate, who are already in the Hall at that position by using their WAR values. Note that Jaffe's system uses the Baseball Reference version of WAR, and the usual caveats about the limitations of WAR apply.

The JAWS rating itself is an average of a player's career WAR and his seven-year WAR peak. Jaffe also assigns one position to a player who may have played at more than one position, choosing the position at which the player contributed the most value; thus, in the table below, Dick Allen is compared against third basemen although he actually played more games at first base. The purpose of JAWS is to improve, or at least maintain, the current Hall of Fame standards at each position to ensure that only players at least as good as average current Hall of Famers are selected for the Hall.

The table below lists all nine players on the 2015 Golden Era ballot, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics, which are explained below the table, as well as the average bWAR and JAWS statistics for all Hall of Fame players at that position. The table also contains the players' ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards, also explained below the table.

| All 2015 Golden Era Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Players (Ranked by bWAR) |

|||||||||

| Player |

Pos. |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

Ave. HoF bWAR |

Ave. HoF JAWS |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Tiant, Luis |

SP |

66.7 |

44.6 |

55.6 |

51 |

73.4 |

61.8 |

97 |

41 |

| Boyer, Ken |

3B |

62.8 |

46.3 |

54.5 |

14 |

67.4 |

55.0 |

86 |

36 |

| Allen, Dick |

3B |

58.7 |

45.9 |

52.3 |

17 |

67.4 |

55.0 |

99 |

39 |

| Pierce, Billy |

SP |

53.2 |

37.8 |

45.5 |

97 |

73.4 |

61.8 |

82 |

35 |

| Miñoso, Minnie |

LF |

50.1 |

39.8 |

45.0 |

22 |

65.1 |

53.3 |

87 |

35 |

| Kaat, Jim |

SP |

45.3 |

38.4 |

44.9 |

101 |

73.4 |

61.8 |

130 |

44 |

| Hodges, Gil |

1B |

44.9 |

34.2 |

39.6 |

34 |

65.9 |

54.2 |

83 |

32 |

| Oliva, Tony |

RF |

43.0 |

38.5 |

40.8 |

32 |

73.2 |

58.1 |

114 |

29 |

| Wills, Maury |

SS |

39.5 |

29.5 |

34.5 |

46 |

66.7 |

54.7 |

104 |

29 |

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

WAR7: The sum of a player's best seven seasons as defined by bWAR; they need not be consecutive seasons.

JAWS: Jaffe WAR Score system—an average of a player's career WAR and his seven-year WAR peak.

JAWS Rank: The player's ranking at that position by JAWS rating.

Ave. HoF bWAR: The average bWAR value of all the Hall of Famers at that position.

Ave. HoF JAWS: The average JAWS rating of all the Hall of Famers at that position.

Hall of Fame Monitor: An index of how likely a player is to be inducted to the Hall of Fame based on his entire playing record (offensive, defensive, awards, position played, postseason success), with an index score of 100 being a good possibility and 130 a "virtual cinch." Developed by Baseball Reference from a creation by Bill James.

Hall of Fame Standards: An index of performance standards, indexed to 50 as being the score for an average Hall of Famer. Developed by Baseball Reference from a creation by Bill James.

With a few isolated exceptions, the various elements used to compare the nine Golden Era player candidates show that the candidates do not measure up to Hall of Fame standards. A few are close, and arguments can be made for them that they are worthy candidates compared to some players already enshrined in the Hall, several of those elected by past Veterans Committees—and as we have seen earlier, some of those committees made some dubious selections.

But because this committee is focusing solely on the Golden Era from 1947 to 1972, it may be helpful to concentrate on only those Hall of Fame players as comparisons to the nine candidates. In other words, how do our nine candidates stack up against their contemporaries already enshrined in the Hall of Fame?

Golden Era Hall of Fame First Basemen

Because these nine player candidates have been identified as belonging to the Golden Era, it may be useful to compare them with their Golden Era contemporaries already in the Hall of Fame. So, starting with this segment and in the following segments, I have grouped each of the nine player candidates with the Hall of Fame players that also played the same position as the candidate. The exception is Dick Allen, who played both first base and third base and is included in the comparisons of Hall of Fame players at both positions; although Allen played more games at first base, Jay Jaffe's JAWS statistics lists him as a third baseman because he provided the greatest value at third.The Hall of Fame players were selected if they played the majority of their careers during the pre-defined Golden Era. I used 1964 as the latest first-year date for the Hall of Fame players because that is the first-year date for Luis Tiant, who had the latest start of the nine candidates.

The purpose of this is simple: If these nine player candidates are to be considered Hall of Fame players from baseball's Golden Era, how do they stack up against other Fame players from that Golden Era who already have been inducted into the Hall of Fame?

Let's start with first base. Here are the five Hall of Fame first basemen associated with the Golden Era and 2015 Golden Era first-base candidates Dick Allen and Gil Hodges, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame First Basemen and 2015 First Basemen Candidates on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| McCovey, Willie |

.270/.374/.515 |

.388 |

64.4 |

67.4 |

147 |

145 |

| Killebrew, Harmon |

.256/.376/.509 |

.389 |

60.3 |

66.1 |

143 |

142 |

| Allen, Dick |

.292/.378/.534 |

.400 |

58.7 |

61.3 |

156 |

155 |

| * Torre, Joe |

.297/.365/.452 |

.365 |

57.6 |

62.3 |

129 |

129 |

| Perez, Tony |

.279/.341/.463 |

.356 |

53.9 |

58.9 |

122 |

121 |

| Cepeda, Orlando |

.297/.350/.499 |

.370 |

50.2 |

50.3 |

133 |

131 |

| Hodges, Gil |

.273/.359/.487 |

.378 |

44.9 |

42.1 |

120 |

121 |

Among their Golden Era contemporaries, Allen compares quite favorably to Willie McCovey and Harmon Killebrew in percentages (slash line, wOBA), value (WAR), and league- and park-adjusted indexes (OPS+, wRC+). In fact, in this sample, Allen is tops in on-base percentage, slugging percentage, wOBA, OPS+, and wRC+. Hodges, on the other hand, lags behind all others in terms of value, and is most comparable to Tony Perez, who is a very marginal Hall of Famer, and whose eventual election by the BBWAA in 2000 is likely due to his being a key component of the Cincinnati Reds' "Big Red Machine" as much as his individual excellence. This is an angle that applies to Hodges's case, as we will examine shortly.

The table below lists the five Hall of Fame first basemen associated with the Golden Era along with Allen and Hodges, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all first basemen in the Hall of Fame.

| 2015 Golden Era First Basemen Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame First Basemen (Ranked by bWAR) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Ave of 19 1B HoFers |

NA |

NA |

NA |

65.9 |

42.4 |

54.2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| McCovey, Willie |

22 |

1959 |

1980 |

64.4 |

44.8 |

54.6 |

12 |

110 |

44 |

| Killebrew, Harmon |

22 |

1954 |

1975 |

60.3 |

38.1 |

49.2 |

19 |

178 |

46 |

| Allen, Dick |

15 |

1963 |

1977 |

58.7 |

45.9 |

52.3 |

NA |

99 |

39 |

| Torre, Joe |

18 |

1960 |

1977 |

57.6 |

37.3 |

47.5 |

22 |

96 |

40 |

| Perez, Tony |

23 |

1964 |

1986 |

53.9 |

36.4 |

45.2 |

26 |

81 |

41 |

| Cepeda, Orlando |

17 |

1958 |

1974 |

50.2 |

34.5 |

42.4 |

30 |

126 |

37 |

| Hodges, Gil |

18 |

1943 |

1963 |

44.9 |

34.2 |

39.6 |

34 |

83 |

32 |

In terms of personality and temperament, Dick Allen and Gil Hodges are poles apart. We will examine Allen more closely in the third baseman segment below. In this segment, we will examine Hodges more closely.

Gil Hodges and "The Boys of Summer"

Gil Hodges is a sentimental favorite for the Hall of Fame—he polled nine of sixteen votes in the last Golden Era Committee ballot—and that sentiment that has been in part fostered and perpetuated by Roger Kahn's 1972 hagiography about the Brooklyn Dodgers, The Boys of Summer. That keynote book profiled the team up to their 1955 World Series victory in relation to Brooklyn native Kahn's life and career as a reporter and writer. Kahn's gushing paean to the "Bums" still informs "the boys of summer," four of whom were Hodges's teammates during this period and who have been enshrined in the Hall of Fame—where, Hodges's supporters insist, Hodges belongs as well.

But does Hodges stack up against his teammates Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, and Duke Snider? The following table lists the qualitative statistics of these Hall of Fame "boys of summer" along with Hodges's.

| Brooklyn Dodgers Golden Era Hall of Fame Position Players and Gil Hodges, Qualitative Statistics Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Snider, Duke |

.295/.380/.540 |

.404 |

66.5 |

63.5 |

140 |

139 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

.269/.366/.377 |

.350 |

66.3 |

64.4 |

99 |

103 |

| Robinson, Jackie |

.311/.409/.474 |

.406 |

61.5 |

57.2 |

132 |

135 |

| Hodges, Gil |

.273/.359/.487 |

.378 |

44.9 |

42.1 |

120 |

121 |

| Campanella, Roy |

.276/.360/.500 |

.385 |

34.2 |

38.2 |

123 |

123 |

| Brooklyn Dodgers Golden Era Hall of Fame Position Players and Gil Hodges, Hall of Fame Comparison Statistics (Ranked by bWAR) |

||||||||||

| Player |

Pos. |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Snider, Duke |

CF |

18 |

1947 |

1964 |

66.5 |

50.0 |

58.2 |

7 |

152 |

47 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

SS |

16 |

1940 |

1958 |

66.3 |

41.0 |

53.6 |

17 |

100 |

39 |

| Robinson, Jackie |

2B |

10 |

1947 |

1956 |

61.5 |

52.1 |

56.8 |

10 |

98 |

38 |

| Hodges, Gil |

1B |

18 |

1943 |

1963 |

44.9 |

34.2 |

39.6 |

34 |

83 |

32 |

| Campanella, Roy |

C |

10 |

1948 |

1957 |

34.2 |

32.8 |

33.5 |

25 |

108 |

39 |

In both sets of data, Hodges generally ranks behind all his "boys of summer" contemporaries except for Roy Campanella, whose slash line, wOBA, OPS+, and wRC+ are roughly equivalent to Hodges's. Campanella, though, suffered misfortune at both ends of his short career: A Negro League player, Campanella's first Major League season was in 1948, following integration the previous year, in his age-26 year. Then, tragically, his career ended following a January 1958 automobile crash that left him paralyzed for the rest of his life. That occurred in what would have been his age-36 year.

Had Campanella not been injured, it is intriguing to consider what the Dodgers would have done with both Campanella and Hodges. As a catcher, Campanella was already in his decline phase before he was injured—in 1957 he started 94 games at catcher, his lowest number since his rookie season—and whether he would have continued as a catcher or have been traded away are points of speculation. However, the Dodgers could have considered moving him to first base—and where would that have left Hodges? Let's note that Hodges had come up as a catcher but was moved to first base to accommodate Campanella. Would Hodges have been moved off first base to accommodate Campanella again?

Again, that is a what-if situation, but it gets to the question of relative value, and of Hodges's specific value. Roy Campanella was named the National League's Most Valuable Player three times (1951, 1953, 1955) during his ten-year career (we'll leave aside whether he deserved the honors), and he finished in the top ten for MVP voting one other time. Jackie Robinson was the NL MVP in 1949, and he finished in the top ten for MVP voting in two other years; Robinson was also the 1947 NL Rookie of the Year—the award is now named for him. Pee Wee Reese was never named MVP but he finished in the top ten for MVP voting eight times. Similarly, Duke Snider was never an MVP but he finished in the top ten six times, with three of those top-five finishes. Hodges had three top-ten MVP-voting finishes and never won the award.

Snider had five consecutive years in which he hit 40 or more home runs, leading the NL in 1956 with 43, and he drove in 100 or more runs six times, leading the NL with 136 in 1955. Hodges hit 40 or more home runs twice and drove in 100 or more runs in seven consecutive seasons, although he never led the league in either category. Campanella hit 41 home runs in 1953, the only time he reached that plateau, while driving in a league-leading 142 runs in that same season, one of three times that he reached that plateau. Campanella, Hodges, and Snider were power-hitting, middle-of-the-order players and are more easily compared to each other, although Robinson, who was not primarily a home-run hitter, actually played more games batting in the cleanup position, and his OPS+ and wRC+ are better than Hodges's. Reese was a table-setter at the top of the order, and his offensive stats cannot match closely to Hodges's—although Reese's batting average and on-base percentage are comparable.

But catcher Campanella, shortstop Reese, second baseman Robinson, and center fielder Snider staffed the core defensive positions up the middle while Hodges was a first baseman, the least demanding defensive position. Granted, Hodges was an excellent-fielding first baseman, winning the first three Gold Glove Awards at that position when the award was introduced in 1957—a greater honor in that inaugural year as the award was presented to only one player at each position across both leagues. However, Hodges's career Range Factor scores are actually lower than the league averages for each statistic: For Range Factor per 9 innings, Hodges posted a 9.56 versus the league's 9.75, and for Range Factor per Game, Hodges had an 8.71 versus the league's 9.67. (For Range Factor per 9 Innings, the equation is put-outs plus assists multiplied by 9, then divided by the number of innings played; for Range Factor per Game, the equation is put-outs plus assists divided by the number of games played.)

Hodges may have been overshadowed by his "boys of summer" teammates, but that is for good reason: Hodges simply wasn't as good as they were in terms of the Hall of Fame. His WAR, JAWS, Hall of Fame Monitor, and Hall of Fame Standards statistics show that he is not even close to the thresholds in comparison either to his storied teammates or to Golden Era first basemen already in the Hall. Aside from the fulsome sentimentality exemplified by Roger Kahn's book, there seems to be a "complete the set" mentality concerning Hodges—all his star "boys of summer" teammates are in the Hall, so why isn't Hodges? That seems to have been the case for Tony Perez, whom even BBWAA voters thought should join his "Big Red Machine" teammates Johnny Bench and Joe Morgan (and presumably Pete Rose should he have been eligible) when they voted Perez into the Hall in 2000. (Coincidentally, the Veterans Committee voted Reds manager Sparky Anderson into the Hall that same year.)

As we have seen in the comparisons above, Hodges and Perez are pretty close to each other in a number of categories. Perez hit for a slightly better average, but Hodges got on base and slugged at a higher percentage. In counting numbers, though, Perez has the edge as he is in the top 60 lifetime in a few key categories: He ranks 57th in hits with 2732 (Hodges ranks 315th with 1921), 55th in doubles with 505 (Hodges is 446th with 295), and 28th in runs batted in with 1652 (Hodges is 125th with 1274), although Perez had more than 2600 more plate appearances than did Hodges, which makes Hodges's 370 home runs to Perez's 379 look that much more impressive. But neither Hodges nor Perez are Hall-worthy.

Where Hodges has another claim to the Hall is as a manager. Following his player retirement during the 1963 season, Hodges became the manager of the Washington Senators until 1967 before becoming the manager of the New York Mets for the 1968 season. The Senators did not have a winning season under Hodges, although in four full seasons the team improved steadily to a 76–85 (.472) mark in 1967. Similarly, the Mets were also a sub-.500 club under him during his first year in New York, but in 1969 Hodges took the "Miracle Mets," who won 100 games and took the National League Pennant, all the way to the World Series, which they won in five games against the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles. Hodges was named The Sporting News Manager of the Year, which in 1969 awarded the honor to only one manager across both leagues. (Note that in 1983 the BBWAA, which votes for Rookie of the Year, Cy Young, and Most Valuable Player awards, instituted its own Manager of the Year award although The Sporting News continues to present its award, and since 1986 it is presented to a manager in each league.)

Here the comparison is to Joe Torre, a near-Hall of Famer as a player who went on to an auspicious managing career, which landed him in the Hall of Fame in 2014. But just as we saw above that Torre's playing record is superior to Hodges's, there is no comparison as a manager. Torre ranks fifth all-time among managers in wins with 2326, against 1997 losses for a .538 winning percentage, winning six pennants along the way. and Torre posted a 84–58 mark (.592) in the postseason, winning four World Series with the New York Yankees; those 84 postseason wins are the best all-time (taking into account that they all came during the current Divisional Era with its three rounds of postseason play, thus greatly expanding the number of postseason games in a season). Hodges posted a 660–753 record (.467) as a manager with one pennant won and one World Series won. Hodges died in 1972, two days shy of his 48th birthday, and thus there is no way to know what Hodges could have accomplished as a manager had he lived.

But you evaluate the baseball you have, not the baseball you wish you had. Hodges's playing record and managing record are not sufficient to call him a Hall of Famer, either singly or together.

Golden Era Hall of Fame Third Basemen

In this segment, we examine the two third basemen candidates named on this year's Golden Era ballot, Dick Allen and Ken Boyer. Allen was evaluated in the preceding segment that examined first basemen as Allen played more games at first base (795 games started; 571 complete games) than at third base (646 games started; 593 complete games). However, Jay Jaffe's JAWS ratings place Allen at third base because he produced his greatest value as a third baseman.Here are the four Hall of Fame third basemen associated with the Golden Era and 2015 Golden Era third-base candidates Dick Allen and Ken Boyer, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame Third Basemen and 2015 Third Basemen Candidates on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Mathews, Eddie |

.271/.376/.509 |

.389 |

96.4 |

96.1 |

143 |

143 |

| Robinson, Brooks |

.267/.322/.401 |

.322 |

78.3 |

80.2 |

104 |

104 |

| Santo, Ron |

.277/.362/.464 |

.367 |

70.4 |

70.9 |

125 |

126 |

| Boyer, Ken |

.287/.349/.462 |

.355 |

62.8 |

54.8 |

116 |

116 |

| Allen, Dick |

.292/.378/.534 |

.400 |

58.7 |

61.3 |

156 |

155 |

| Kell, George |

.306/.367/.414 |

.362 |

37.6 |

38.2 |

112 |

111 |

Boyer, on the other hand, has been considered a poor man's Ron Santo, and as the slash lines above indicate, they are very similar—Boyer hit for a better average, Santo had a better on-base percentage (he led the National League in that category twice and in walks four times), and their slugging averages are a wash. Both played for 15 seasons, but Santo played in roughly 200 more games with about 1100 more plate appearances, which gives him the edge in counting numbers (hits, doubles, home runs, runs scored and runs batted in). Boyer won the NL Most Valuable Player award in 1964 when he led the NL in RBI with 119.

Both third basemen won five Gold Gloves each. Boyer was probably the better defensive third baseman: Baseball Reference calculates his defensive Wins Above Replacement (dWAR) at 10.6 while Santo's is 8.6, and the site calculates Boyer's Total Zone Total Fielding Runs above Average, the number of runs above or below average a fielder was worth based on the number of plays made, at 73 while Santo clocks in at 20. FanGraphs gives Boyer the edge over Santo in Defensive Runs Above Average (the number of runs above or below average a fielder is worth on defense; it combines fielding runs and positional adjustment), with Boyer's 105.7 topping Santo's 69.5, although—oddly—FanGraphs rates Santo higher in Total Zone Number of Runs Saved, with Santo indexed at 27 while Boyer is at 7.

Defensively, Allen is a tremendous hitter. Allen's overall dWAR is –16.5 while his overall Defensive Runs Above Average is –152.2; at third base, Allen rates a –45 in Total Zone Total Fielding Runs above Average and a –46 in Total Zone Number of Runs Saved.

The table below lists the four Hall of Fame third basemen associated with the Golden Era along with Allen and Boyer, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all third basemen in the Hall of Fame.

| 2015 Golden Era Third Basemen Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Third Basemen (Ranked by bWAR) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Mathews, Eddie |

17 |

1952 |

1968 |

96.4 |

54.3 |

75.4 |

2 |

162 |

54 |

| Robinson, Brooks |

23 |

1955 |

1977 |

78.3 |

45.8 |

62.1 |

8 |

152 |

34 |

| Santo, Ron |

15 |

1960 |

1974 |

70.4 |

53.8 |

62.1 |

7 |

88 |

41 |

| Ave of 13 HoFers |

NA |

NA |

NA |

67.4 |

42.7 |

55.0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Boyer, Ken |

15 |

1955 |

1969 |

62.8 |

46.3 |

54.5 |

14 |

86 |

36 |

| Allen, Dick |

15 |

1963 |

1977 |

58.7 |

45.9 |

52.3 |

17 |

99 |

39 |

| Kell, George |

15 |

1943 |

1957 |

37.6 |

27.8 |

32.7 |

48 |

90 |

29 |

Ken Boyer is a promising candidate but doesn't quite measure up as a deserving Hall of Fame inductee. Dick Allen is a more intriguing proposition.

The Intriguing if Troubled Career of Dick Allen

Beginning his career in the mid-1960s, Allen is a fitting presence in that turbulent decade—controversial, outspoken, misunderstood, and ultimately mistreated. As an African-American, Allen endured racial harassment even before he joined the Philadelphia Phillies as he became the first black player on the Phillies' minor-league affiliate in Little Rock, Arkansas, at the time still one of the most racially divisive regions in the United States. (Recall that only a few years before, in 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus had called out the state National Guard to prevent the integration of Little Rock Central High School, a move that was countered by President Dwight Eisenhower when he sent federal troops to Little Rock to ensure the students' safety.)

But when Allen joined the parent club for his first full season in 1964, he merely became the National League's Rookie of the Year when he led the league in runs (125), triples (13), and total bases (352)—and also strikeouts (138)—while collecting 201 hits, slugging 38 doubles and 29 home runs, posting an impressive slash line of .318/.382/.557, generating a 162 OPS+, and driving in 91 runs. Allen was one of the true bright spots in a season that saw the Phillies, who had been in first place for most of the season, fall into a horrendous slump during the final weeks of the season and lose the pennant, one of the most notorious collapses in baseball history. Yet Allen did not endear himself to Phillies fans—indeed, not only did they hurl insults and racial epithets at him, they began to hurl physical objects at him, prompting Allen to wear a batting helmet as he played the field, which earned him the nickname "Crash," short for "crash helmet." Even his teammates threatened him, such as Frank Thomas (not the 2014 Hall of Fame inductee), a known racist who wielded a bat at Allen in an infamous 1965 incident that saw Thomas ejected from the team.

As a result, Allen demanded to be traded from the Phillies. He was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals (who had eventually taken the NL pennant in 1964, with its own third baseman, Ken Boyer, winning the MVP award) in 1970, and found himself again a part of history: One of the players for whom he was traded was Curt Flood, who famously refused to be traded without his consent; Flood's protest, though ultimately futile, did eventually lead to the dismantling of baseball's Reserve Clause and to the current free-agency environment. Allen's short stay in St. Louis was relatively uneventful, and he was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers, for whom he played one season before being dealt to the Chicago White Sox. (He was traded for Tommy John, who himself would make history for the arm surgery now named for him.)

In his first year with the White Sox, Allen owned the American League: He led the AL in home runs (37), RBI (113), bases on balls (99), on-base percentage (.420), slugging percentage (.603), and, retrospectively, OPS+ (199) while batting .308 and even stealing 19 bases, one shy of his career-high 20 in 1967. Allen walked away with the MVP award, garnering 21 of the 24 first-place votes, and was certainly the best position player in the league that year. But a serious leg injury curtailed his 1973 season, and although he rebounded the following year, his age-32 season, with a .301/.375/.563 slash line and a league-leading 32 home runs (he also led the AL in slugging percentage), Allen quit the White Sox with two weeks to go in the 1974 season, claiming a feud with Ron Santo, in his last season before retirement, was to blame. Allen announced his own retirement following the season, but he was lured back to, of all places, Philadelphia. However, his previous injury and the onset of his decline phase meant that Allen had seen his best seasons already pass him by. He retired for good following the 1977 season, after an undistinguished part-time year with the Oakland Athletics.

In terms of offensive effectiveness, Dick Allen is probably the most potent of the six position-player candidates on the Golden Era ballot. Minnie Miñoso and Tony Oliva could hit for average and get on base, and Gil Hodges hit more home runs (370) than did Allen (351), but Allen could do all of that impressively—and he is the only one of the six with a slugging percentage above .500. Allen's counting numbers cannot match up with career leaders, and apart from his sensational 1964 rookie season and his masterful 1972 MVP season, Allen did not have a streak of dominance that would indicate an incipient Hall of Fame talent; apart from his rookie campaign and his MVP season, he had only one other year in which he finished in the top ten for MVP voting: in 1966, when he placed fourth after generating a .317/.396/.632 slash line—that .632 slugging average led the NL—hitting 40 home runs, and driving in 110 runs.

Offensively, Dick Allen is the best candidate on the 2015 Golden Era ballot, but he falls just short of the Hall of Fame.

Golden Era Hall of Fame Left Fielders

Turning to the left fielder on the Golden Era ballot, Minnie Miñoso, we find that he is among some of the most auspicious names in the Hall of Fame.Here are the seven Hall of Fame left fielders associated with the Golden Era and 2015 Golden Era left-field candidate Miñoso, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame Left Fielders and 2015 Left Field Candidate on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Williams, Ted |

.344/.482/.634 |

.493 |

123.1 |

130.4 |

190 |

188 |

| Yastrzemski, Carl |

.285/.379/.462 |

.375 |

96.1 |

94.8 |

130 |

130 |

| Williams, Billy |

.290/.361/.492 |

.376 |

63.5 |

60.4 |

133 |

132 |

| Stargell, Willie |

.282/.360/.529 |

.387 |

57.5 |

62.9 |

147 |

145 |

| Miñoso, Minnie |

.298/.389/.459 |

.382 |

50.1 |

50.8 |

130 |

133 |

| Kiner, Ralph |

.279/.398/.548 |

.427 |

49.3 |

47.6 |

149 |

147 |

| Brock, Lou |

.293/.343/.410 |

.336 |

45.2 |

43.2 |

109 |

109 |

| * Irvin, Monte |

.293/.383/.475 |

.389 |

21.4 |

20.8 |

125 |

127 |

The table above has two significant outliers: At the top, Ted Williams is ridiculously overqualified for the Hall, as befits one of the greatest hitters in baseball history, and although Williams was in his decline phase in the 1950s as Miñoso was in his prime (a decline relative to Williams, that is—he still led the American League in batting in 1957, his age-38 season, with a .388 average while crushing 38 home runs, tied for the second-highest single-season total of his career), it was still Miñoso's misfortune to be a left fielder in the same league as Williams. At the other end of the scale, Monte Irvin played just eight seasons in the major leagues, but he was elected to the Hall of Fame by a special Negro Leagues Committee, having not entered the majors until 1949, his age-30 season—and we will address Minnie Miñoso and baseball's integration below.

So, if we toss out the two outliers in this sample of Golden Era left fielders in the Hall of Fame, we see Miñoso essentially identical to the other five players in terms of slash line, wOBA, OPS+, and wRC+. In WAR, he falls behind Carl Yastrzemski, who is another outlier in this category because of his longevity, Billy Williams, and Willie Stargell, but Miñoso is ahead of Ralph Kiner, whose career was cut short by injury by his age-30 year, and Lou Brock.

The table below lists the seven Hall of Fame left fielders associated with the Golden Era and Miñoso, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all left fielders in the Hall of Fame.

| 2015 Golden Era Left Field Candidate, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Left Fielders (Ranked by bWAR) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Williams, Ted |

19 |

1939 |

1960 |

123.1 |

69.2 |

96.2 |

2 |

354 |

72 |

| Yastrzemski, Carl |

23 |

1961 |

1983 |

96.1 |

55.5 |

75.8 |

4 |

215 |

60 |

| Ave of 19 HoFers |

NA |

NA |

NA |

65.1 |

41.5 |

53.3 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Williams, Billy |

18 |

1959 |

1976 |

63.5 |

41.3 |

52.4 |

11 |

122 |

48 |

| Stargell, Willie |

21 |

1962 |

1982 |

57.5 |

38.0 |

47.7 |

15 |

106 |

44 |

| * Miñoso, Minnie |

15 |

1949 |

1964 |

50.1 |

39.8 |

45.0 |

22 |

87 |

35 |

| Kiner, Ralph |

10 |

1946 |

1955 |

49.3 |

43.7 |

46.5 |

19 |

136 |

34 |

| Brock, Lou |

19 |

1961 |

1979 |

45.2 |

32.0 |

38.6 |

35 |

152 |

43 |

| Irvin, Monte |

8 |

1949 |

1956 |

21.4 |

21.3 |

21.3 |

102 |

18 |

18 |

In terms of WAR and JAWS statistics, Miñoso falls below the average marks for all left fielders in the Hall of Fame, but so does everyone in this sample except for Ted Williams and Yastrzemski. And apart from Irvin, who played just eight major-league seasons, Miñoso falls short in both Hall of Fame Monitor and Hall of Fame Standards ratings.

Furthermore, Miñoso's 15 seasons (not counting his guest appearances in 1976 and 1980) are the fewest in this sample except for Kiner, whose career was cut short by injury by age 30, and Irvin, who did not enter the majors until age 30. Miñoso himself did not play in his first Major League game until 1949, during his age-23 year, and that amounted to nine games and 20 plate appearances with the Cleveland Indians. Prior to that, he had spent three seasons in the Negro Leagues. This prompts the central question of Miñoso's candidacy, which is whether, as a black Latino, he would have compiled a more impressive playing record—and thus have boosted his chances for the Hall of Fame—had he come into the majors earlier in his career. Let's explore that possibility now.

Is Minnie Miñoso the Latino Jackie Robinson?

After three seasons in the Negro Leagues from 1946 to 1948, Minnie Miñoso was signed as a free agent by the Cleveland Indians in 1948. That season, he played a few games for the Indians' Single A affiliate the Dayton (Ohio) Indians before jumping to the parent club's Triple A affiliate the San Diego Padres the following year, for whom he played two full seasons, with a brief call-up to Cleveland in 1949 before making the majors for good in 1951.

Miñoso began that season with the Indians before being traded to the Chicago White Sox as part of a three-team trade (the Philadelphia Athletics being the third team) on April 30. The next day, in his first at-bat with the White Sox, Miñoso hit a 415-foot home run off the very first pitch he saw from the New York Yankees' Vic Raschi, and he was in business with the Sox. That year, Miñoso was the AL Rookie of the Year runner-up to the Yankees' Gil McDougald, and although the voting was fairly close (of the two candidates, McDougald polled 54 percent to Miñoso's 46 percent), in hindsight Miñoso looked to be the stronger candidate—he posted a .326/.422/.500 slash line while leading the AL in triples (14), stolen bases (31), and being hit by a pitch (16), the first of ten times he would lead the league in that category. Miñoso also finished fourth in MVP voting in 1951, and he would go on to finish fourth in MVP voting in three more seasons, with a career top-ten finish in MVP voting totaling five altogether.

Throughout the 1950s, Miñoso continued to be a star player both offensively and defensively, leading the AL in hits once, doubles once, triples three times, and stolen bases three times—as well as caught trying to steal a base six times—in a ten-year period from 1951 to 1960. Miñoso also won a Gold Glove for his defensive play during the first three of the four years the award had been in existence, and like Gil Hodges's win in 1957, Miñoso's win in that year is even more auspicious because there was only one Gold Glove awarded to a specific position for both leagues. Following a good if not noteworthy 1961 campaign in his age-35 year, Miñoso became a part-time player for three years before retiring following the 1964 season.

As we saw previously, Miñoso was a one-and-done in his first time on a Hall of Fame ballot in 1969, netting less than two percent of the vote. However, the White Sox engineered a pair of publicity stunts in 1976 and in 1980 in which Miñoso returned, at age 50 in 1976 and age 54 in 1980, to take a handful of at-bats and thus become the only player in Major League history besides Nick Altrock to play in five different decades. However, the ploy restarted Miñoso's clock with respect to the Hall of Fame—starting in 1986, Miñoso remained on 14 straight ballots, averaging about 15.2 percent of the vote with a high of 21.1 percent in 1988.

Now Minnie Miñoso's chances for the Hall of Fame rest with the Golden Era Committee, and the argument for Miñoso's inclusion is that he is a pioneer—the first star player from a Latin American country, predating Roberto Clemente, and thus is the "Latin Jackie Robinson"—one who also faced discrimination: As a black Cuban, Miñoso spent three years playing in the Negro Leagues at the cusp of baseball's integration before signing with the Cleveland Indians. The Indians were the first American League team to integrate when center fielder Larry Doby played his first major league game less than two months after Robinson did.

Doby saw limited action in 1947 but became a full-time player the following year; he remained the Indians' center fielder through the 1955 season, when he was traded to the White Sox and, fittingly enough, became Miñoso's teammate once again. Larry Doby was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1997 by the Veterans Committee; Doby had an excellent career although on numbers alone he does not look like a Hall of Famer, and his induction is recognition—belated recognition, to be sure—that Doby faced the same daunting challenges as did Jackie Robinson but received nowhere near the attention that Robinson did. Now a similar argument has been put forth for Minnie Miñoso.

The following table lists qualitative statistics for Minnie Miñoso and selected Golden Era Hall of Fame players who played in the Negro Leagues before becoming Major Leaguers, ranked by bWAR.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame Negro Leagues Players and Minnie Miñoso, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||||

| Player |

Age at MLB Debut* |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

|

| Robinson, Jackie |

28 |

.311/.409/.474 |

.406 |

61.5 |

57.2 |

132 |

135 |

|

| Miñoso, Minnie |

23 |

.298/.389/.459 |

.382 |

50.1 |

50.8 |

130 |

133 |

|

| Doby, Larry |

23 |

.283/.386/.490 |

.396 |

49.5 |

51.1 |

136 |

137 |

|

| Campanella, Roy |

26 |

.276/.360/.500 |

.385 |

34.2 |

38.2 |

123 |

123 |

|

| Irvin, Monte |

30 |

.293/.383/.475 |

.389 |

21.4 |

20.8 |

125 |

127 |

|

The table below lists Minnie Miñoso and selected Golden Era Hall of Fame players who played in the Negro Leagues before becoming Major Leaguers, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards.

| Minnie Miñoso Qualitative Comparisons to Golden Era Hall of Fame Negro Leagues Players, Ranked by bWAR |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Robinson, Jackie |

10 |

1947 |

1956 |

61.5 |

52.1 |

56.8 |

10 |

98 |

38 |

| Miñoso, Minnie |

15 |

1949 |

1964 |

50.1 |

39.8 |

45.0 |

22 |

87 |

35 |

| Doby, Larry |

13 |

1947 |

1959 |

49.5 |

39.6 |

44.6 |

20 |

72 |

30 |

| Campanella, Roy |

10 |

1948 |

1957 |

34.2 |

32.8 |

33.5 |

25 |

108 |

39 |

| Irvin, Monte |

8 |

1949 |

1956 |

21.4 |

21.3 |

21.3 |

102 |

18 |

18 |

Would Miñoso have compiled a more Hall of Fame-worthy record had he entered the Majors as a full-time player before his age-25 season in 1951? Did he experience additional prejudice because he was both black and Latino? Is Miñoso indeed the Latino Jackie Robinson, a trailblazer for Latin players who deserves to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame because of it?

Strictly as a player, Miñoso has always been on the borderline as a Hall of Famer. Add that playing record to his status as the first Latino star, and it would not be surprising if the Golden Era Committee voted Miñoso into the Hall. It would be similar to previous acknowledgements of Monte Irvin, a star in both the Negro Leagues and in the Major Leagues, and particularly of Larry Doby, overshadowed by Jackie Robinson but no less a pioneer. Moreover, and despite the huge influx of Latin players into the majors in the last three decades, a Miñoso election would be a reminder that Latinos struggled with prejudice and discrimination as well, and it is not an issue that has been resolved.

When Arizona passed a state senate bill, SB 1070, in 2010 that targeted illegal immigrants and initially featured draconian measures regarding racial profiling, not only civil rights groups but even Major League Baseball itself protested its extremity, with high-profile Latino players such as Adrian Gonzalez and Albert Pujols stating publicly that they opposed the bill. Why? Arizona borders Mexico, and SB 1070 cannot help but target Latinos. There was talk about players boycotting the 2011 All-Star Game to be held in Phoenix; however, that talk—and any action—fizzled by the time the game was actually played, although by that time the more extreme elements of SB 1070 had already been struck down. (I wrote about the reaction to SB 1070, including a possible boycott, just prior to the 2011 All-Star Game.) And in 2012, Torii Hunter, who will get some Hall of Fame consideration when he retires, generated some controversy with his remarks about Latino players—and, apropos of Miñoso, black Latino players in particular—when he labeled them "imposters" and "not black." Hunter himself is African-American.

Although Hunter's remarks were tactless and impolitic, they do raise a point with respect to how situations are different between African-American players and Latino players. Both groups did—and do—face prejudice and discrimination. But the circumstances between the two groups are much different, and they should give pause to those simply equating Minnie Miñoso with Jackie Robinson.

The African-American experience in American history and society is unique. No other group was forcibly taken from their native lands in Africa and brought to North America to work as slaves. No other group was counted as three-fifths of a human being for representation and taxation purposes as described in the Three-Fifths Compromise portion of the United States Constitution. (Technically, black slaves were not explicitly named in the Constitution as counting as three-fifths of a human being—the language in Article 1, Section 2, Paragraph 3 states it as "three fifths of all other Persons"—but the historical context and intent make clear what group is being referred to.) Following emancipation from slavery, which precipitated the American Civil War, blacks were still subject to segregation in the American South (and tacit discrimination in many areas outside the South). This practice was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in its 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which immortalized the expression "separate but equal" as doctrinal law, and it was not struck down legally until another landmark Supreme Court ruling in 1954, Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, seven years after Jackie Robinson, and then Larry Doby, had led the drive to integrate Major League Baseball.

By contrast, Minnie Miñoso came from Cuba to the United States voluntarily: He had been offered a deal to play for the New York Cubans in the Negro National League in 1946. (And unlike Cuban players who even today are said to have fled Cuba's political repression, Miñoso had left Cuba 13 years before Fidel Castro and the communists took power in Cuba in 1959.) Two years later, and one year after baseball's color line had been broken, Miñoso had been signed by the Cleveland Indians at age 22. True, he didn't earn a full-time job in the majors until 1951, his age-25 season.

Did baseball's color line rob Miñoso of seasons in which he could have compiled an even stronger career playing record? Did the Cleveland Indians fail to fully recognize Miñoso's potential, or did they deliberately ignore it? Or did the Indians simply not have a place for him at the time they signed him? Or did Miñoso, in his first, limited action with the club in 1949, in which he batted .188 with one home run in nine games and 20 plate appearances, simply not impress the club, which thought he needed minor-league seasoning before he would be ready for the majors? And did any of these situations barring the first have anything to do with prejudice or discrimination based on Miñoso's being a Latino, or even a black Latino?

We may never know the answers to these questions, but one point is clear: As an immigrant, even a black immigrant from a Spanish-speaking country, Miñoso's experience was not the same as Jackie Robinson's, or Larry Doby's, or any other African-American player. Miñoso may have faced prejudice and discrimination, as have countless immigrants throughout American history, but those immigrants chose to leave their native countries and come to the United States. For African-Americans, though, the United States is their native country, albeit one they did not originally choose willingly, and it is within their native country that they have struggled for status equal to all other Americans—to be regarded as more than three-fifths of a human being for accounting purposes. That is why the African-American experience is unique, and that is why Miñoso's experience ultimately cannot be compared to Jackie Robinson's or Larry Doby's or any other pioneering African-American player. This may be what Torii Hunter was struggling to convey in his maladroit remarks about Latino players, particularly black Latino players—the sense of resentment that the immigrants' experience is equivalent to the African-Americans'.

And if baseball collectively is in such a self-congratulatory mood concerning its record of social pioneering, it may want to remember that the next time Marvin Miller and even Curt Flood are considered for the Hall of Fame. After all, their efforts led to the dismantling of the Reserve Clause, which historically had made players in essence chattel, or property, of the teams for which they played, to be used and discarded as the teams saw fit without any regard for the players' wishes—and without regard to a player's race, creed, or color.. The efforts of Flood and Miller led to the current economic environment of free agency, which has been as powerful and as revolutionary to baseball as had been integration, affecting all players be they African-American (such as Torii Hunter) or black Latino.

So, does Minnie Miñoso belong in the Hall of Fame, based on his playing record, his pioneering status, or both? His case is not as clear-cut as his proponents would argue, but neither is it unfounded. Previous veterans committees have elected players with substantially weaker cases; Miñoso would not be the worst inductee by a fair margin. Although I am, in the last analysis, not opposed to his induction, I cannot consider his playing record strong enough by itself for the Hall of Fame, and I have little more than lukewarm enthusiasm for his status as a pioneering Latino player being a non-playing factor in his Hall of Fame case.

Golden Era Hall of Fame Right Fielders

Moving to the other corner outfield spot, we find another Cuban whose playing record is on the bubble. And although Tony Oliva entered major league baseball in 1962, at a time when Latino players were becoming commonplace, the bigger hurdle he faces in a Hall of Fame assessment is his competition among right fielders already in the Hall—as we will see below, Oliva's contemporaries in right field are among the best whoever played the position.Here are those five Hall of Fame right fielders associated with the Golden Era along with Oliva, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame Right Fielders and 2015 Right Field Candidate on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Aaron, Hank |

.305/.374/.555 |

.403 |

142.6 |

136.3 |

155 |

153 |

| Musial, Stan |

.331/.417/.559 |

.435 |

128.1 |

126.8 |

159 |

158 |

| Robinson, Frank |

.294/.389/.537 |

.404 |