Ballot Overview

The fifteen nominees are the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Chic, Green Day, Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, Kraftwerk, the Marvelettes, Nine Inch Nails, N.W.A., Lou Reed, the Smiths, the Spinners, Sting, Stevie Ray Vaughan, War, and Bill Withers. Six artists are on the ballot for the first time while nine have been nominated previously:- Two artists are eligible for the ballot for the first time this year: Green Day and Nine Inch Nails.

- Four artists have been eligible for the ballot in previous years and are on the ballot for the first time: The Smiths, Sting, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Bill Withers.

- Three artists are returning to this year's ballot from the 2014 ballot: The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Chic, and N.W.A.

- Six artists have been on previous ballots but were not on the 2014 ballot: Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, Kraftwerk, the Marvelettes, Lou Reed, the Spinners, and War.

| 2015 Nominee |

Nominated Previously |

Number of Times Nominated Previously |

Last Time Nominated |

| The Paul Butterfield Blues Band |

Yes |

3 |

2014 |

| Chic |

Yes |

8 |

2014 |

| Green Day |

No |

NA |

NA |

| Joan Jett and the Blackhearts |

Yes |

2 |

2013 |

| Kraftwerk |

Yes |

2 |

2013 |

| The Marvelettes |

Yes |

1 |

2013 |

| Nine Inch Nails |

No |

NA |

NA |

| N.W.A. |

Yes |

2 |

2014 |

| Lou Reed |

Yes |

2 |

2001 |

| The Smiths |

No |

NA |

NA |

| The Spinners |

Yes |

1 |

2012 |

| Sting |

No |

NA |

NA |

| Stevie Ray Vaughan |

No |

NA |

NA |

| War |

Yes |

2 |

2009 |

| Bill Withers |

No |

NA |

NA |

With a total of nine chances for the bouquet, Chic has been a bridesmaid longer than anyone on this ballot. Bill Withers has been eligible since 1996, the longest eligibility period of any artist on the ballot who has never been nominated. However, the Spinners and the Marvelettes have both been eligible since the first year that the Hall began inducting artists, 1986, with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, first eligible in 1988, not far behind them. Meanwhile Lou Reed has waited longer than any previously-nominated artist for his current nomination, since 2001, and should Reed be elected, it would be a posthumous induction.

Overall, the ballot reflects an emphasis on the 1970s and 1980s, with a handful of 1960s acts (the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Marvelettes, the Spinners) acting as the deep historical choices, although the Spinners sustained front-line visibility into the Disco Era. Chic, Kraftwerk, Lou Reed, War, and Bill Withers all had their heydays in the 1970s, with Reed and to a lesser extent Chic and Kraftwerk soldiering on into the 1980s, and for Reed, beyond that. Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, the Smiths, Sting, and Stevie Ray Vaughan established their presences in the 1980s, while Green Day, Nine Inch Nails, and N.W.A. used the tail-end of that decade as their springboard into the 1990s and beyond, although N.W.A. was a short-lived act.

Ballot Criteria: Theirs, Yours, and Mine

Last year, I examined the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's primary criterion for defining what composes a Hall of Fame-caliber musical act, "musical excellence," and I noted that the Hall does not actually define just what it means by "musical excellence." Inquiring readers are encouraged to read further from last year's article, but for our purposes here I will simply repeat the entire statement of eligibility from the Hall of Fame's own website, which is as follows:To be eligible for induction as an artist (as a performer, composer, or musician) into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the artist must have released a record, in the generally accepted sense of that phrase, at least 25 years prior to the year of induction; and have demonstrated unquestionable musical excellence.

We shall consider factors such as an artist's musical influence on other artists, length and depth of career and the body of work, innovation and superiority in style and technique, but musical excellence shall be the essential qualification of induction. [Emphases added.]

The Hall does emphasize aesthetic reflection and aesthetic judgment as important concepts in helping to determine "musical excellence" (they are also listed in the glossary of terms). Those definitions of aesthetic reflection and aesthetic judgment are key concepts worth examining; from the Hall's glossary:

Aesthetic reflection: The act of becoming aware of one's own process of understanding and responding to the arts, and of examining how others respond to artistic expression.

Aesthetic judgment: The ability to form and articulate a critical argument based on aesthetic criteria.

Everyone who expresses an opinion on whether an artist belongs in the Hall of Fame follows those two concepts to arrive at that opinion. How well we formulate that opinion is a function of individual bias and limitations, with the correspondingly wide variance both in the range and in the quality of that opinion.

In essence, though, this is a two-stage operation. First, with aesthetic reflection, we sort out why it is that we respond favorably or unfavorably toward a certain form, style, or genre of music, and toward individual artists within those forms, styles, and genres. Developing a conscious understanding of why we like or dislike different types of music and different artists helps toward the next step of then being able to evaluate those types of music and those artists.

However, that is a big next step because that requires us to not only recognize why we like or dislike a musical type or musical artist, but to recognize why someone else may like or dislike a musical type or musical artist—and, more importantly, why that musical type or artist may be significant regardless of how we feel about it. Music appreciation is an intensely emotional experience, and it is overwhelmingly subjective, but it is possible to put our individual judgments into perspective, into a picture of the overall body of music of the Rock and Soul Era, to try to determine the significance of a musical type and a musical artist within that overall picture as the basis for evaluation.

None of which helps with defining what exactly the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame means by "musical excellence," particularly as it regards "musical excellence" as the overriding factor in whether an artist is worthy of the Hall of Fame. In political statecraft, the term "national security" serves the same function: It is never defined but it is used to justify war-making capabilities, invading other countries, enacting potentially oppressive laws, and spying on everyone including the state's own citizens. That ranges a bit far afield for our purposes here, but it illustrates how a broad, vague term lacking clear definition enables any and every kind of action, with the corresponding consequences.

Regardless of what "musical excellence" may actually mean, I have developed what I call Defining Factors to assess whether an artist is worthy of inclusion into the Hall of Fame. These five Defining Factors are:

Innovation. The artist has invented or refined one or more aspects of the music.

Influence. The artist has made a demonstrable impact on the music of either contemporaries or succeeding artists.

Popularity. The artist has achieved an appreciable measure of commercial or critical success.

Crossover appeal. The artist is recognized and appreciated outside the artist's primary arena.

Legacy. The artist's accomplishments have lasting impact and appeal.

To be considered a Hall of Fame act, I think that an artist must rate as highly as possible in as many Defining Factors as possible. I developed these Defining Factors during my series of "audits" of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's selections from 1986 to 2013 (the sixth and latest installment contains links to the previous five installments).

Unlike the Hall of Fame, though, I maintain that the "essential qualification of induction" is not "musical excellence"—again, whatever that might mean—but rather legacy. This is implied in the Hall's one unequivocal criterion for eligibility, which is that an artist is not eligible until twenty-five years have elapsed from the release of the artist's first recording. This enables historical perspective, to put the artist into context within the overall continuum of the Rock and Soul Era to assess whether the artist really has had an impact on the music and, to a greater extent, on the culture that fostered the music.

In essence and in fact, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is a museum, an institution designed to evaluate and recognize how the past has shaped our present and how it may suggest our future. Simply put, seeing an artist in the Hall of Fame means that the artist had some significant bearing on the music. The term "significant" is a notoriously subjective one, one that becomes an ill-defined and -placed boundary separating those artists who are worthy from those who are not. Perhaps this is the elusive "musical excellence" of the Hall's statement?

Nevertheless, as I have done for my assessment of the 2013 and 2014 ballots and for my six "audits" of the artists already in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I have used my Defining Factors to assess the fifteen nominees for the 2015 ballot. And no matter how much aesthetic reflection and aesthetic judgment I use, these assessments cannot help but reflect my own biases and limitations.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band

Background: This home-grown outfit was among the first to explore American blues rock but found itself overshadowed by the spate of British acts that leapt to prominence in the mid-1960s from the Rolling Stones on down. The irony is that the Paul Butterfield Blues Band learned at the feet of the Chicago masters and at times even featured members of Howlin' Wolf's bands. Led by singer and harmonica player Paul Butterfield, who picked up his instrumental cues from Little Walter, and highlighted by guitarists Mike Bloomfield—arguably the greatest white blues guitarist you've never heard of—and Elvin Bishop, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band released a self-titled debut album for Elektra Records in 1965 that was a high-energy, if overly literal, distillation of Chicago blues—from "Born in Chicago" to "Mellow down Easy" to "Look over Yonder's Wall"—that spotlighted both Butterfield's and Bloomfield's impressive chops.The next album, 1966's East-West (Elektra), was even better as the band blended jazz and even East Indian influences into its blues-rock core, the former with a cover of Nat Adderley's "Work Song" and the latter with the lengthy title instrumental: "East-West" was a revolutionary track that stood at the forefront of the extended instrumental workouts soon to be found in psychedelia and in the next wave of blues-rock jamming—the seeds of the Allman Brothers' guitar interplay, for instance, can be found here in Bishop's and Bloomfield's fretwork. When Bloomfield departed, Butterfield regrouped with a horn-based approach, as exemplified by 1967's The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw (Elektra) that anticipated the big-group jazz-R&B sound soon to be associated with Blood, Sweat and Tears and the Chicago Transit Authority as well as with Bloomfield's own short-lived Electric Flag. However, Butterfield's curse was being able to forecast trends but being unable to capitalize on them, either through inadequate songcraft or modest arrangements that, barring exceptions such as "East-West," didn't fully explore the implications he had uncovered.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. With its third nomination in as many years, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band either has been close in recent voting or it has one or more champions on the nominating committee. However, the presence of Stevie Ray Vaughan on this year's ballot may siphon this possible groundswell of support that is keeping this band alive as the blues or blues-rock pick. Regardless, this is still an act that appeals to aficionados and not to general listeners—in other words, a marginal one.

Would I vote for the artist? No. Although it might be unfair that the British blues rockers nabbed the spotlight from Butterfield and his band, it is not unjustified—they used the form as a springboard to more substantial developments. Butterfield did anticipate a number of musical trends but he couldn't translate them into commercial success or significant influence.

Chic

Chic has been nominated for the Hall an unprecedented nine times.

Background: Blending rock and R&B influences into its bouncy disco strategy, Chic offered a grittier, funkier take on dance music, and in the process provided inspiration for hip-hop and rock artists—the hit "Good Times," and particularly Bernard Edwards's rubbery bass line, provided the bedrock for, among others, the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight" and for Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust." Edwards also provided another signature low-register classic for the risqué smash "Le Freak" as he and guitarist Nile Rodgers, both veteran session men, crafted the earthy foundation of Edwards's thick bottom and Rodgers's chicken-scratch guitar—funk elements dating back to James Brown's JBs—that supported the washes of strings and the airy voices of the female singers whose words carried an undertone of social unease even as the overt message was to "Dance Dance Dance," another key hit for the collective.

Chic offered a durable approach for disco, but by the 1980s the genre was getting buffeted, and the band had often been unfairly cast as relics of that period, exemplified by the seeming vacuity of tracks such as "I Want Your Love" and "Everybody Dance." Yet Chic developed a hybrid sound that proved accessible not only to dance styles—Chic's contemporary Sister Sledge bore a literal relationship to Chic's sound—but also to urban, hip-hop, and rock styles, while the full yet economical production work of Edwards and Rodgers, the hallmark of Chic's success, quickly became in-demand, thus perpetuating Chic's influence. As any number of the anonymous disco bands from that period fade into nostalgia, the impact and influence of Chic becomes more salient.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? Yes. This is Chic's ninth nomination, and with no other disco act on the ballot this year, its supporters on the nominating committee must believe that a majority of voters will check the Yes box if only to keep Chic from appearing on subsequent ballots. With Donna Summer elected two years ago, and last year's Hall and Oates induction still relatively fresh in voters' minds, the consensus could be that dance music may in fact be more significant than thought previously.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Admittedly a borderline pick, Chic nevertheless transcends its primary genre, disco, while influencing various styles. Its impact on hip-hop pioneers Grandmaster Flash and the Sugarhill Gang alone is an indication of Chic's impact on the development of music of the Rock and Soul Era, even crossing over into hard rock (cf. Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust").

Green Day

Green Day is eligible for the Hall for the first time this year.

Background: Combining the energy and candor of punk- and underground rock with an undeniable pop appeal, Green Day may offend purists but it has done as much to keep stripped-down but increasingly smarter rock before a mass audience as have—dare we say it?—Nirvana. The trio—singer and guitarist Billy Joe Armstrong, singer and bassist Mike Dirnt, and drummer Tré Cool (Frank Wright)—channeled suburban disaffection and ennui into compact outbursts that over time evolved from brash adolescence to surprisingly reflective maturity while seldom abandoning the essential elements of rock and roll: hard-driving guitar, bass, and drums, and a passionate voice with a point of view.

After two albums of indie-label woodshedding, Green Day exploded onto the mainstream stage with 1994's Dookie (Reprise), which marshaled head-snapping rockers ("Basket Case," "She," and the compelling "Welcome to Paradise") with the more considered observations of "Longview" and the confident swagger of "When I Come Around" to establish the band as instant heavyweights. After Dookie's runaway success, the follow-up Insomniac (Reprise, 1995) couldn't help but seem disappointing—but in addition to showcasing the band's continuing maturity, Insomniac rocked harder and more convincingly, led by the punchy gem "Brain Stew," the high-velocity "Jaded," and instantly familiar "Stuck with Me," while "Walking Contradiction" streamlined previous attitudes into more than a cocky pose. Green Day's ambition soared on Nimrod (Reprise, 1997), sampling various styles (even surf instrumentals with "Last Ride In") with varying degrees of success, although its pop-punk approach remained largely intact on the Hüsker Dü-like blur of "Nice Guys Finish Last" and the Stray Cats-styled stomper "Hitchin' a Ride," while "Redundant" reached back to 1970s power-pop arrangements and "Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)," its surface magnanimity masking subtle barbs, found Green Day fully immersed in the ballad game.

That acoustic approach informed 2000's Warning (Reprise), which drew from folk as it turned its gaze toward social issues, its relative drop in commercial success counterbalanced by the band's rising critical esteem. "Minority" made its political statements explicit while "Macy's Day Parade" slyly disguised its insightful commentary as it and the droll, clever "Warning" recalled Paul Westerberg and the Replacements; meanwhile, "Waiting" seemed to reach all the way back to the Beatles for inspiration. Warning set the stage for 2004's American Idiot (Reprise), a full-blown concept album about the antihero "Jesus of Suburbia" and his search for truth, meaning, love—or something—and while Green Day may have ultimately overreached itself (the title of "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" itself is a howling cliché, not to mention the song's musical resemblance to Oasis's "Wonderwall"), it did show the band and its principal songwriter Armstrong continuing to develop and mature. In any case, the album spawned a successful stage version and a film version still in development, and by now Green Day, its career path now advancing in the same fashion as Pink Floyd and the Who, could hardly be ignored.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? Yes. Green Day's story is much like that of Nirvana's, which opened the path for Green Day in the first place, albeit with a happier ending: Band crystallizes a brash hard-rock sound with immediate commercial appeal, and in Green Day's case band is able to progress to the point that its work transcends the music world and broaches the broader reaches of pop culture. Probably the closest thing to a sure bet on the 2015 ballot.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Complaints about Green Day's being derivative are almost beside the point in the face of the band's ability to internalize its influences and inspirations into a truly appealing musical and lyrical approach. Green Day's songs sound instantly familiar, and before you've worked out just where you've heard them before they have hooked themselves into your ear and have become enduring. The kicker is an increasing intelligence born of disaffection but savvy enough to make itself accessible.

Joan Jett and the Blackhearts

Background: Singer and guitarist Joan Jett might have had a lurid start as a member of the punk-bait Runaways, but once she went solo in the late 1970s, she quickly established herself as a genuine hard-rocker informed by punk chops and attitude. The title song to Jett's debut Bad Reputation (Boardwalk, 1981, although it had been issued the previous year as an eponymous self-release) announced her defiant presence with a brash bash, as did the hit title-track declaration from her follow-up album, I Love Rock 'n' Roll (Boardwalk, 1981), with the Blackhearts now fully in tow. That album featured another hit, an intriguing cover of "Crimson and Clover"—intriguing because Jett couldn't change the gender of the song's subject without changing the lyrics—but that also underscored the defining characteristic of Jett's career: She has been primarily a juke box, churning out a host of cover versions (including an entire album of them titled The Hit List for Blackheart/CBS Records in 1990) that showcases her taste and knowledge—with some, such as her take on Lesley Gore's pre-feminist anthem "You Don't Own Me," being downright inspired—but not necessarily her artistic ability. (Even "I Love Rock 'n' Roll" was a cover of Arrows' mid-1970s single.)Granted, Jett has recorded a number of her own compositions, and some of them have gained success, such as "I Hate Myself for Loving You" (albeit written with song doctor Desmond Child), although many of her own songs seem to scream "issues": "Let Me Go," "Don't Abuse Me," "Love Is Pain," "Victim of Circumstances," "You're Too Possessive," "Fake Friends," and "This Means War" among them. The psychological interpretations are best left to her therapist, and Jett is hardly alone in airing her grievances in song, but apart from "Let Me Go" and a couple of others, they don't make for memorable rock songs, certainly compared to the verve she brings to her renditions of "I Love Rock 'n' Roll," "Do You Wanna Touch Me," "You Don't Own Me," and "Everyday People." As an inspiration to riot grrrls and other female rockers, Jett comes on like Chrissie Hynde's kid sister, and that sums up Jett's problem: She has never stepped out from the shadows of others to establish herself as an artist in her own right.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? Yes. Joan Jett looks like the kind of female rocker Hall voters would love to embrace—brash and post-punk but with a firm attachment to the classic-rock legacy through all those cover versions. Not that the voting won't be close, but compared to some of the nominees the Hall has elected, Joan Jett is not the worst.

Would I vote for the artist? No. Joan Jett doesn't rise to the level of a Hall of Famer in terms of Defining Factors. Her musical approach is derivative and hardly innovative, and it doesn't carry much insight or lasting appeal. As a hard rocker, she is generally enjoyable but ultimately non-essential.

Kraftwerk

Kraftwerk exerted an influence on later styles including electronica and hip-hop.

Background: Given that Germany, until the late 1960s, had no rock tradition but did have a technocratic one dating back much earlier than that, it is no surprise that it should spawn an initial wave of "krautrock" that emphasized electronic, synthesized sounds from bands such as Faust, Kraftwerk, and Tangerine Dream. (Can, also of that generation, pursued similar technological sounds only using more organic instrumentation.) With a penchant for simplicity and hypnotic repetition, along with flashes of deadpan humor, Kraftwerk, formed in 1970 by multi-instrumentalist mainstays Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, was the most accessible of the lot. That accessibility in turn translated to influence.

The lengthy title tracks to the 1970s albums Autobahn (Phillips/Vertigo, 1974) and Trans-Europe Express (Kling-Klang/EMI-Electrola/Capitol, 1977) evoked impressions of a long car trip and railroad trip, respectively, while exemplifying the monotonous yet lulling rhythm of both modes of transportation, enlivened occasionally by a passing distraction; in that respect, Kraftwerk manifested into rock the influences of fellow German electronic pioneer Karlheinz Stockhausen as well as American composer Steve Reich. Kraftwerk also displayed a droll sense of humor ("Showroom Dummies," with its sly shock of recognition for Doctor Who fans, and "The Model," which prefigures the supermodel phenomenon), all the more salient for coming from "humorless German engineers" forecasting the age of robots and computers ("The Man-Machine," "Computer World").

In fact, the Teutonic technocrats get quite punny on the bilingual (English and German) Radio-Activity (Kling Klang/EMI/Capitol, 1975), both verbally and aurally, as the album title and "Radioactivity" allude to both the communication medium and radiation, with the latter also getting its hearing on "Geiger Counter" and "Uranium," although "Radio Stars" is hardly a tribute to Jack Benny or the Lone Ranger but to pulsars and quasars instead (while also nodding musically to Tangerine Dream); meanwhile, "Airwaves" may fondly—if oddly—remind you of the theme music to Star Trek, and if you've heard the Chemical Brothers' "Leave Home," then you've heard the opening sample from "Ohm Sweet Ohm" (hah sweet hah!).

Kraftwerk's minimalist approach got old fairly quickly—by the early 1980s the band was repeating itself to no benefit—but by offering a stark, shiny, hypnotic sound from the future, it provided a tangible influence on avant-garde, hip-hop (Africa Bambaata's seminal "Planet Rock" was built upon "Trans Europe Express"), and New Wave while laying the foundation for electronica, which owes a significant debt to Kraftwerk and its forecasting the form a decade or two before it became pervasive.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? Yes. Hall voters seem to be coming to terms with modern rock and pop styles, and part of that acceptance is acknowledging the influences on those styles. Voters will also be defusing criticism that they are biased toward American and British artists by making Kraftwerk the first German artist elected to the Hall.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Albeit it is a reluctant yes, as I do not think that Kraftwerk's body of work beyond Autobahn and Trans-Europe Express is remarkable. However, much like Black Sabbath, Kraftwerk exerted an influence that transcended its own artistic limitations. It is that influence and legacy, though, that pushes these "transistorized pranksters" (to borrow critic David Fricke's expression) into the Hall.

The Marvelettes

Background: One of Motown's earliest hit-makers, notching their only Number One single "Please Mr. Postman" in 1961, the Marvelettes were also one of the most anonymous of the Motown ensembles. That relative facelessness resulted in the group being overlooked as the label's solo artists and high-profile members of other groups became known quantities, but although the Marvelettes delivered Motown's first Number One hit ("Please Mr. Postman"), they were soon eclipsed by these more talented artists.The girl-group did reach the Top Forty through 1968 as "Playboy," "Beechwood 4-5789," "The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game," "My Baby Must Be a Magician," and especially the winsome "Don't Mess with Bill" all made at least Number 20 on Billboard's Hot 100 pop singles chart. But the Marvelettes never abandoned the ultimately limiting format of the anonymous girl-group ensemble—Wanda Rogers eventually emerged as the group's singing personality, although she paled in comparison to Diana Ross and even Martha Reeves—and despite Smokey Robinson's guidance (he provided them with "Don't Mess with Bill," sung by Rogers), Motown relegated the Marvelettes to background status, and after "My Baby Must Be a Magician," they did begin to fade like the smoke from a conjuring trick.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. Hall voters have been overly zealous in backfilling earlier artists, particularly from the 1960s, but Motown, justly so, is well-represented in the Hall of Fame, and the Marvelettes do not rise to the level of their more illustrious label mates.

Would I vote for the artist? No. The Marvelettes provided a handful of engaging hits throughout the 1960s, and although they were able to adapt to a number of production styles, they lack strong Defining Factors to qualify them for the Hall.

Nine Inch Nails

Nine Inch Nails has been a most visible industrial-rock artist.

Background: Industrial rock had been simmering beneath the punk-rock surface since the late 1970s, and it accrued underground cachet throughout the 1980s, but it took Nine Inch Nails to thrust industrial into the mainstream—no small feat as the band has made few lyrical or musical concessions since its 1989 debut Pretty Hate Machine (TVT). That album featured one performer almost exclusively, Trent Reznor, and although Reznor has used a plethora of musicians on subsequent releases and concert tours, Nine Inch Nails has been the vehicle for Reznor's angst-ridden outbursts incorporating sex, politics, and religion (Pretty Hate's "Sanctified" and "Something I Can Never Have"), even as "Down in It" and "Head Like a Hole" demonstrated considerable pop accessibility. Going the Ministry route, NIN replaced the synth-pop of Pretty Hate Machine with a metal attack on the brutal 1992 EP Broken (TVT/Nothing), with remixes subsequently released as Fixed, as uncompromising tracks such as "Happiness in Slavery" and the hit "Wish" ushered the band into the ranks of influential noise merchants of the 1990s, with Reznor's lyrical and melodic hooks propelling him above the pack.

The Downward Spiral (Nothing, 1994)upped the ante as the concept album about suicide not only kept up the electro-metal assault but drew its inspiration from earlier experimental- and progressive rock (particularly David Bowie's Low); prog-rock stalwart Adrian Belew (King Crimson, Talking Heads, Frank Zappa) supplies distinctive guitar. The album contained the band's signature song "Closer" while the blistering "March of the Pigs" maintained the edgy aggression, and the jarring dynamics of "Mr. Self Destruct" chronicled the clashing social and personal upheaval. Subsequent recordings found Nine Inch Nails working through the implications of the sound it had found with mixed success, although With Teeth (Interscope, 2005) still proffered a catchy thumper in "The Hand That Feeds," and Year Zero (Interscope, 2007) was a full-blown examination of future political dystopia that was ultimately uneven and suggested that Reznor's insights were more effective in concentrated doses.

But as Reznor and Nine Inch Nails have continued to record and tour, their legacy has been established, and at this point it is simply a matter of updating the résumé. Reznor has garnished his reputation by supplying songs for film soundtracks and, with musician and composer Atticus Ross, has scored three David Fincher films, winning an Academy Award for The Social Network (2010), and establishing industrial rock as a mainstream genre—you cannot escape it even in the safety of your MultiPlex cinema.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? Yes. Hall voters may be holding their noses as they check this box, but they also know that few acts have—perhaps no other act has—pushed industrial into the mainstream with such forceful conviction as has Nine Inch Nails.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Industrial music has remained murky and anonymous, but Trent Reznor and Nine Inch Nails have given it both a face and a voice, in turn making industrial a rock genre to be reckoned with as they have inspired subsequent musicians. Moreover, Nine Inch Nails's lyrical and musical contributions have helped to shape the course of contemporary rock.

N.W.A.

N.W.A. changed hip-hop with its album Straight Outta Compton.

Background: Sometimes the history of the Rock and Soul Era is punctuated by artists whose moment was brief but enduring, altering the course of the music irrevocably even though the artist's presence was fleeting. Bill Haley, the Sex Pistols, and Grandmaster Flash were such artists, and so was the hip-hop group N.W.A. Short for Niggaz wit Attitudes, N.W.A. wasn't the first gangsta-rap act—Schoolly D delivered the first truly graphic street-level vignettes (such as "PSK—What Does It Mean?), although Hall of Fame recognition for him is non-existent; first is not always lasting—but N.W.A. did deliver the definitive tract for the genre, Straight Outta Compton (Ruthless/Priority/EMI, 1988), N.W.A.'s second album, which has influenced countless acts while spawning the solo careers of Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, and Ice Cube. "Straight Outta Compton" is a gripping statement of purpose while "Gangsta Gangsta" details inner-city life in ambiguous terms and the notorious "Fuck tha Police" is a landmark challenge to authority that eerily presaged the 1991 Rodney King beating in Los Angeles and the subsequent rioting following the acquittal of the four L.A. police officers charged with the beating.

And that was it for N.W.A. Its first album was a tepid exercise that could hardly predict the impact Compton would have, and its releases subsequent to that quickly became uninspired and parodic. Furthermore, internal disputes ensured that N.W.A. would not last long, with Dr. Dre and Ice Cube embarking on substantial careers while Eazy-E, who also went solo, died in 1995. By that time, gangsta rap had become the dominant hip-hop genre while exerting a fascination throughout contemporary music and pop culture in general. N.W.A. had ratcheted up the stark storytelling of Grandmaster Flash and Run-D.M.C. while echoing the bluntness of rock's hardcore underground, and it pushed the Rock and Soul Era into a graphic, profane existence. Like it or lump it, you cannot ignore it.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. This is despite the fact that the decks are cleared for N.W.A.—there is no other hip-hop act on this year's ballot—and the group seems to have backing in the nominating committee if it has made the ballot for three years in a row. Nevertheless, given the still-contentious nature of hip-hop being in the "Rock and Roll" Hall of Fame, I still don't see Hall voters voting for thiship-hop act anytime soon. Which doesn't mean that I don't hope that I'm dead wrong about that.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Although N.W.A.'s legacy amounts to only one album, its impact is what matters, and the band redirected the course of hip-hop, with a corresponding ripple effect on other musical and cultural forms, as a result of it. N.W.A. is the hip-hop equivalent of the Sex Pistols, and it will be interesting to see, if it is elected, if the group regards its election as a "piss stain" as well.

Lou Reed

Background: With a solo career that dates back to the early 1970s, Lou Reed has always divided opinion—critical darling, bête noire, underrated genius, overrated poseur—while his considerable output has similarly been uneven. Reed is already in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as the leading light of the Velvet Underground (inducted in 1996), while his solo material, stretching across four decades until his 2013 death at age 71, provides as many reasons to disqualify him as it does to recommend him.Reed struck early with 1972's Transformer (RCA), which yielded the signature hit "Walk on the Wild Side"—Velvet Underground decadence diluted for Top 40 radio, albeit with "giving head" sneaking in nevertheless—while "Perfect Day" and "Satellite of Love" operated between the Velvets and David Bowie, who produced the album, and "Vicious" was a coolly ironic rocker. Berlin (RCA, 1973) was an ambitious song cycle that often seemed trapped between Cabaret and The Rocky Horror Show ("Caroline Says"). Sally Can't Dance (RCA, 1974) was uninspired time-filling—the title song plucked pieces from whatever pop trends caught Reed's fancy that day—while the live album Rock 'n' Roll Animal (RCA) from that same year enlisted a crack hard-rock band, including guitarists Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner, to pump up Reed's Velvets classics (including "Sweet Jane" and "Rock and Roll") to arena-level anthems (critic Ira Robbins deemed it "unbelievably bombastic"), which left Reed a sideman on his own material. But Metal Machine Music (RCA, 1975) signaled Reed's nadir: an interminable electronic drone and feedback exercise that functioned as commercial and critical suicide—although you know that an avant-garde quarter or two heralded it as subversive genius.

Such is the impact of Lou Reed. Also released in 1975, Coney Island Baby (RCA) tried to smooth ruffled feathers with the pleasantly languid title song; Reed's feint toward Leonard Cohen, "A Gift"; and another itchy rocker, "She's My Best Friend." Encouragingly, Street Hassle (Arista, 1978) aimed for the Big Statement of Berlin with better results (the title suite, "I Wanna Be Black," "Real Good Time Together"), although as punk and new wave pushed the old guard, including Reed, to the side, Reed's opportunity to snap up the grail seemed to have passed.

Or did it? Reed's early-1980s albums—he was back with RCA for The Blue Mask (1982), Legendary Hearts (1983), and New Sensations (1984)—promised a renaissance; the first two, recorded with legendary punk guitarist Robert Quine, offered stripped-down rockers and ballads in the Velvets' mode but with a definite contemporary feel, while New Sensations actually aimed for upbeat fun ("My Red Joystick"). Mistrial (RCA, 1986) tried to mix drum programming and social comment with middling results, but when Reed returned to minimalist rock with New York (Sire, 1989), he may have made the best album of his solo career: Although references to Jesse Jackson and Kurt Waldheim, among others, date the record now, New York contains Reed's most cogent songwriting, an unsentimental observation of events both global and local. "Dirty Blvd." was a hit, while "Sick of You" remains a timeless rant, and "Dime Store Mystery" is an elegy of sorts for Velvet Underground mentor Andy Warhol. Reed and former Velvets bandmate John Cale collaborated on Songs for Drella (Sire, 1990), a full-fledged memorial to Warhol, and as Reed moved through the 1990s and into the 21st century, his less-frequent releases exhibited increasingly elegiac airs, with The Raven (Sire, 2003) a grand homage to Edgar Allan Poe, until his own death in 2013.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. Despite his passing last year, Lou Reed has never engendered widespread sympathy previously and is unlikely to do so now, although this year may be Reed's best shot at the Hall as he remains fairly fresh in the memory. Reed's reputation is scattered across various perceptions—subversive pioneer (and already covered with his induction with the Velvet Underground), punk inspiration, sardonic singer-songwriter, casually caustic rocker—and it is hard to see the overall groundswell of support coalescing to vote him in.

Would I vote for the artist? No. Lou Reed's solo career, which lasted a good four or five times longer than his career with the Velvets, has been a classic case of arrested development. Over the years, he has matured, to the point that New York remains a bracing statement although it is not a brilliant one, certainly not musically—although that is admittedly deliberate on Reed's part—but also not lyrically, either, no matter how intelligent Reed's observations are. Overall, Lou Reed's solo legacy is that of a minor talent whose reach exceeded his grasp.

The Smiths

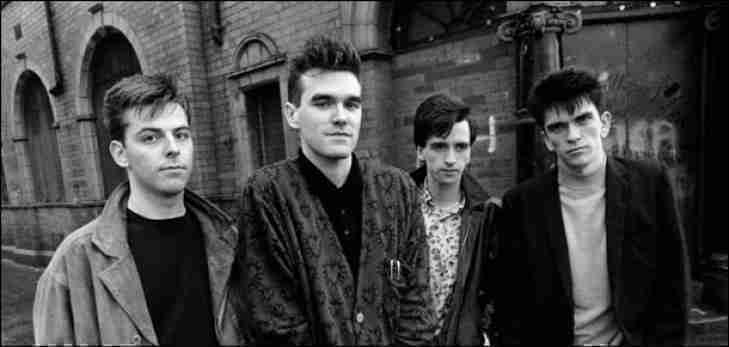

The Smiths were one of the most popular and influential bands of the 1980s.

Background: Hugely popular in Great Britain, the Smiths straddled the mainstream and the underground, the former through a shimmering, gorgeous jangle-pop approach that glided on ball bearings, and the latter through the singular, idiosyncratic, immediately distinctive voice and lyrics of lead singer Morrissey (first name Steven), whose keening, vulnerable persona and mannered air make Brian Ferry look and sound like Wilson Pickett. The Smiths' atmospheric mopery initially brooked comparisons with the romantic gloom of acts such as Depeche Mode and Spandau Ballet, although the Smiths parted company right away starting with their ordinary-sounding name—a direct repudiation of such pretentious appellations as Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark—to their shunning of synthesizers; instead, the band wedded the chiming, melodic, often multi-tracked guitars of Johnny Marr and the sturdy rhythm team of bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce to Morrissey's warbling, winsomely self-absorbed ruminations and rode them to post-punk glory.

Amazingly, the Smiths accomplished all this in the space of about five years in the mid-1980s, the band's output totaling four full-length studio albums and a passel of non-album singles. The first single, "Hand in Glove," memorably told us that the sun shines out of our behinds but made little initial impact; however, the follow-up "This Charming Man" struck gold while introducing the coy, teasing themes of homosexuality that helped to inform Morrissey's outlook, which came to encompass asexuality, celibacy, and the effects of child abuse among other deliberately non-commercial subjects. The Smiths' 1983 self-titled debut album for Rough Trade elaborated further with a remixed version of "Hand in Glove" while "Reel around the Fountain" was a lovely if ravaged ballad, and the elliptical, equivocal "What Difference Does It Make?" became another hit. The engaging single-only "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now" sharpened the Smiths' appeal as it became one of the band's signature songs (reference to Caligula notwithstanding); another non-album single, the compulsive, gently propulsive "How Soon Is Now?" made inroads in the United States. However, the band's second album Meat Is Murder (Rough Trade, 1985), although overtly political and bravely confrontational, seemed too strident despite—or because of—its condemnation of corporal punishment ("The Headmaster Ritual") and its support for depressives ("That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore") and vegetarianism (the title song).

The band rebounded with The Queen Is Dead (Rough Trade, 1986), which sharpened Morrissey's mordant wit into sardonic humor—if you believe that, in "Bigmouth Strikes Again," he is pulling our leg about knowing how Joan of Arc felt—and also sharpened Marr's guitar-driven hooks into sonic candy. "Cemetery Gates" and the unabashed "Never Had No One Ever" dared you not to cherish them as bruised and vulnerable plaints, as did the ethereal "The Boy with the Thorn in His Side," while the driving, U2-like title track was an oblique, fascinating rail covering personal and social politics, and "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" is the wryly winsome ballad that should have conquered America. It didn't, but Louder Than Bombs (Rough Trade/Sire, 1987), a compilation aimed at the US market, came fairly close with its lode of choice singles ("William, It Was Really Nothing," "Sheila Take a Bow," "Shoplifters of the World Unite"). The Smiths' final studio album, Strangeways, Here We Come (Rough Trade, 1987), tried to broaden the band's musical attack, but despite a standout or two ("Girlfriend in a Coma," "Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before") it ended the Smiths' career on a disappointing note. Morrissey went on to a notable solo career; the other Smiths, not so much.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. The Hall loves British bands, but with its American bias, it all but demands that those bands have had significant success in the States—how else to explain the induction of the Dave Clark Five? Unfortunately, the Smiths' American success amounts to a strong cult following and a couple of singles (particularly "How Soon Is Now?") that somehow stumbled onto the American dance chart.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Not only did the Smiths encapsulate bracing 1980s attitudes with an appealing, accessible sound topped by a truly distinctive frontman in Morrissey, but those yearning, mournful emotions, spiked with an acid wit, proved to be influential on the next wave of alternative navel-gazers and social misfits, echoed in the emo movement and elsewhere. The Smiths carried the banner for latchkey kids, secondary school outcasts, the sexually confused, and the socially awkward everywhere.

The Spinners

The Spinners began their career in the early 1960s and are still performing.

Background: You may be forgiven for thinking, "Wait a minute—aren't the Spinners already in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?" With a career that stretches back to the early 1960s, this soul singing group has been a fixture of the classic rock and soul period, and, with lead singer Philippé Wynne and songwriter-producer Thom Bell, a hit-making machine in the 1970s, the group's heyday; thus, their inclusion in the Hall seems a foregone conclusion. Yet the Spinners may have been too polite to attract serious attention: Lacking the brooding melodrama of the Four Tops, or the lean, sharp moods of the O'Jays, or even the histrionics of Percy Sledge, the Spinners, particularly during the Wynne-Bell years, made their sentiments seem too effortless, as if they came too easily and thus eluded appreciation.

The Spinners tasted their first singles success in 1961 with the doo-wop-inflected "That's What Girls Are Made For," recorded with lead singer Bobby Smith for Harvey Fuqua's Tri-Phi Records. The group failed to chart a follow-up, but the Fuqua connection got them a spot on the Motown roster, where their 1965 single "I'll Always Love You" snuck into the lower reaches of the Top 40, but the pleasant if unexceptional plaint was easily overshadowed by the label's heavyweights (a fate similar to the Isley Brothers), and it took another five years for another hit, writer-producer Stevie Wonder's "It's a Shame," which featured the game falsetto of lead singer G.C. Cameron.

Signing to Atlantic but losing Cameron, the Spinners picked up singer Wynne and producer Bell, and under Bell's tutelage the group released the low-key, heavily arranged "How Could I Let You Get Away" in 1972. It failed to dent the Top 40, but then Bell and the group, with a pair of charismatic leads in Smith and Wynne, sharpened their approach—and the floodgates opened: the engaging "Could It Be I'm Falling in Love," "One of a Kind (Love Affair)," "Mighty Love," the funky "I'm Coming Home," "Love Don't Love Nobody," and the relaxed, swinging confidence of "I'll Be Around" were unabashed ear candy that all made the Top 20 between 1972 and 1974, culminating with their chart-topper recorded with Dionne Warwick, the swirling, incandescent "Then Came You." Even the de rigueur social commentary of "Ghetto Child" was appealing enough to chart. By the mid-1970s, Bell's formula was losing its luster—"Sadie," "Wake up Susan," "You're Throwing Good Love Away," and "Heaven on Earth (So Fine)" all missed the Top 40—although the instant charm of "Games People Play" and the hilarious funk of "The Rubberband Man" were both undisputed hits. Moreover, the Spinners' albums Spinners (Atlantic, 1973), Mighty Love (Atlantic, 1974), and Pick of the Litter (Atlantic, 1975) were substantial works in and of themselves—not merely hits-plus-filler packages.

Wynne left the Spinners in 1977, and the group parted company with Bell by 1979; the Spinners managed a pair of hits at the turn of the decade with the disco-inflected medleys "Cupid"/"I've Loved You for a Long Time" and especially "Working My Way Back to You"/"Forgive Me, Girl" before they moved onto the oldies and nostalgia circuit, their legacy already established.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. With Chic, the Marvelettes, War, and Bill Withers also on the ballot, the easy charm of the Spinners is liable to be overlooked by voters. The group's biggest strength, instant accessibility, is also its biggest curse, which is why it took until 2012 just to get them on a ballot for the first time.

Would I vote for the artist? Yes. Percy Sledge is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—and the Spinners are not. In case that needs elaboration, the Spinners were among the top hitmakers of the 1970s, with an irresistibly engaging ensemble sound that helped to define the period. The Spinners have been long overdue for the Hall.

Sting

Background: When the Police halted operations in the mid-1980s, Sting (born Gordon Sumner), the band's lead singer, bassist, and principal songwriter, was tapped as the trio's best solo bet, and as if on cue he released his first solo album, The Dream of the Blue Turtles (A&M), in 1985. Reflecting Sting's jazz roots—jazz musicians backing Sting included saxophonist Branford Marsalis, keyboardist Kenny Kirkland, and drummer Omar Hakim—it was a critical and commercial success that spawned a number of hits including "Fortress around Your Heart," "Love Is the Seventh Wave," and a solo signature of sorts in "If You Love Somebody Set Them Free"; all three exemplified Sting's tendency toward keening romantic sentiment, although the topical songs "We Work the Black Seam," an ode to coal miners, and especially "Russians," an overwrought Cold War observation that even a cop from Sergei Prokofiev cannot ameliorate, suggested that he should leave politics to his former Police mate Stewart Copeland (whose father was, after all, a high-ranking field operative for the Central Intelligence Agency). The soundtrack to Bring on the Night (A&M, 1986), Michael Apted's documentary about Sting's budding solo career, underscored the jazz emphasis with live tracks that also featured Police songs.But with . . . Nothing Like the Sun (A&M, 1987) and The Soul Cages (A&M, 1991), Sting made like Paul Simon and went international, particularly Latin as the former album prompted an EP, . . . Nada Como el Sol (A&M, 1988), that featured five tracks from Sun rendered in Spanish or Portuguese including "They Dance Alone," about Chileans disappeared under the Pinochet regime. Both albums were informed by the deaths of his parents, with The Soul Cages being particularly somber, although each managed hit singles, Sun with "We'll Be Together" and "Be Still My Beating Heart" (and the less said about Sting's embalming of Jimi Hendrix's "Little Wing" the better), and Cages with the title song and "All This Time." Sting lightened up with Ten Summoner's Tales (A&M, 1993), which yielded hits in "If I Ever Lose My Faith in You" and "Fields of Gold," although his self-important cleverness was becoming irritatingly cloy—yes, we know you were a teacher once and even managed to rhyme "Nabokov" in a Police song—a trait perpetuated in subsequent albums such as Mercury Falling (A&M, 1996) and Brand New Day (A&M, 1999), culminating with Sting's songs getting the orchestral treatment with Symphonicities (Deutsche Grammophon, 2010), by which time Sting had become fully regarded as being as insufferable as he is talented.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. It may be a close vote as Sting has become the darling of middle-aged listeners wanting both sophisticated music and an articulate lyrical outlook. And with his previous success fronting the Police, Sting looks like his generation's Paul Simon. But Sting's urbane persona is polarizing, and voters may check the No box based on negative perception alone.

Would I vote for the artist? No. Sting has enjoyed a successful solo career, and his embrace of first jazz and then international styles has given him the veneer of a musicologist à la Paul Simon. However, despite some commercial and critical success, Sting does not rate highly enough in the Defining Factors to merit inclusion in the Hall of Fame strictly on his solo output.

Stevie Ray Vaughan

Background: Cutting through the moping swirl of early-1980s synth-pop with the ringing, steely-sharp slice of his Stratocaster, Stevie Ray Vaughan emerged from Texas as the Great White Hope of blues rock, a genuine guitar hero with a sound as singular as B.B. King, Carlos Santana, and Jimi Hendrix. Fostered by legendary impresario John Hammond, Vaughan first came to notice, curiously enough, in 1983 on David Bowie's hit album Let's Dance (EMI), on which Vaughan's squalling fills gave notice to somebody distinctive in the mix. Vaughan's debut album, Texas Flood (Epic, 1983), recorded with Double Trouble, the solid if unspectacular rhythm duo of bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Chris Layton, contained an exciting if familiar mix of rockers ("Love Struck Baby," "Pride and Joy") and rave-ups ("Rude Mood," "Testify") while the slower numbers (the title track, the instrumental "Lenny") gave Vaughan space to stretch out his estimable playing, particularly in concert. Vaughan's follow-up Couldn't Stand the Weather (Epic, 1984) augmented its blues rock ("Cold Shot," a strident cover of "The Things (That) I Used to Do") with jazz flourishes (the nimble title song) and, with "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)," Vaughan's explicit nod to a seminal influence, Jimi Hendrix.But although Soul to Soul (Epic, 1985) sounded richer thanks to the addition of keyboardist Reese Wynans, who added crucial texture to the slower-tempo numbers "Ain't Gone 'n' Give up on Love" and "Life without You" (which still found the haze of Hendrix hanging over it) as well as on the rollicking cover of Hank Ballard's "Look at Little Sister," Vaughan had yet to make his mark as more than just a Stratocaster master. Perhaps the substance abuse that afflicted Vaughan and the band was the culprit. In 1986 the band released a concert set, Live Alive (Epic), a standard holding action and one that was heavily overdubbed in post-production to bolster the decent though hardly exceptional live renditions that include a cover of Stevie Wonder's "Superstition" and the wonderfully droll recounting of a gangster's flamboyant funeral, "Willie the Wimp." However, In Step (Epic, 1989) found Vaughan both newly sober and inspired by it; while "Tightrope" and especially "Wall of Denial" are the confessions of a recovering addict, their acute musicianship buoys Vaughan's other concerns such as the rambunctious opener "The House Is Rockin'," the gorgeous, reflective closing instrumental "Riviera Paradise" (with its tip of the hat to Lone Star jazz guitarist Kenny Burrell), and Vaughan's undisputed blues-rocker classic "Crossfire," capped by Vaughan's wrenching, quintessential guitar solo.

Then, tragically, as Stevie Ray Vaughan finally seemed set to grab the brass ring as not only a guitar titan but also as a recording and performing artist, he was killed on August 27, 1990, in a helicopter crash while leaving a concert in Wisconsin. Vaughan's premature death left his legacy largely unrealized although the spate of posthumous releases reminds listeners of Vaughan's promise, with The Sky Is Crying (Epic, 1991) a particularly strong artifact, offering the acoustic reminiscence "Life by the Drop" as the Texas guitar slinger's epitaph.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? Yes. With a tone as big and bold as Texas, Stevie Ray Vaughan looks like the Last Guitar Hero, the standard-bearer of the old guard who took on the ascendance of modern rock in the 1980s almost single-handedly. Hall voters will appreciate his old-school approach enough to reward him.

Would I vote for the artist? No. The tragic aspect to Stevie Ray Vaughan's career is that his life was cut short just as he was beginning to truly develop as an artist; that is doubly so as he had cleaned himself up from a near-lifetime of addiction and stood poised to realize his potential, only to be killed in an accident over which he had no control. But although Vaughan is undoubtedly one of the great guitarists in rock history, the recorded legacy he left behind does not support that perception.

War

Background: With a cosmopolitan, even catholic attitude toward popular music, War prefigured some of the genre blending and crossover approaches two decades before that became commonplace, while the band's best efforts remain a source of samples and inspiration for hip-hop. War's roots lie in Southern California, incorporating local African-American and Latin influences into its basic funk style, but early on it picked up a Jewish producer, Jerry Goldstein, a Dutch harmonica player, Lee Oskar, and, at least initially, an English singer in Eric Burdon, the former front man for two variants of the Animals. Burdon's narration helped "Spill the Wine," still a War touchstone, become an engaging hit with its vaguely internationalist feel, but on War's first two albums with Burdon, his psychedelic tendencies overwhelmed the band (two separate covers of "Nights in White Satin"!). Even un-Burdoned, War still needed an album to sharpen its focus: War (United Artists, 1971) flexed the band's lean, loose-limbed drive and warm group vocals ("Lonely Feelin'," "Sun Oh Son"), although the ham-handed anti-Castro jab "Fidel's Fantasy" found the band still developing its political commentary.The band honed that on All Day Music (United Artists, 1971) with "Get Down" and especially the brilliant urban tale "Slippin' into Darkness," keyed to Oskar's harmonica and B.B. Dickerson's bass (both of which suggest an inspiration for Bob Marley's "Get Up, Stand Up"), while the title song promised jazz-inflected good times. Even better was the 1972 chart-topping album The World Is a Ghetto (United Artists), its hit title song expressing that sentiment with lyrical and musical eloquence as "The Cisco Kid," echoing the Latino hero of the 1950s Western television series, reinforced the multicultural identification; meanwhile, the country-funk instrumental "City, Country, City" showcased War's musical ability. Deliver the Word (United Artists, 1973) suggested a hint of gospel (the title song) while the hard-driving "Me and Baby Brother" and a shortened version of "Gypsy Man" became hit singles. Bolstered by a pair of signature hits in the throbbing, tightly-wound "Low Rider" and the infectious, hilarious camaraderie of "Why Can't We Be Friends?," Why Can't We Be Friends? (United Artists, 1975) actually signaled the end of War's heyday. Platinum Jazz (Blue Note, 1976) was anything but, while the title track of Galaxy (MCA, 1977) was inspired by Star Wars, with the corresponding superficiality—more troubling was the game disco moves it displayed, indicating yet another band threatened by the next trend and trying desperately to stay au courant.

Indeed, War never regained its touch as it entered the 1980s—the 1981 single "Cinco de Mayo" was a discofied re-write of "Low Rider"—and the band began to grind it out, releasing the occasional album for the fanbase while hitting the oldies and nostalgia circuit. But hip-hoppers didn't forget about War, and the best elements of this sturdy funk-rock band have served to enhance succeeding generations of musicians.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. Despite a mid-1970s clutch of strong albums and memorable singles, War never captured sufficient attention to make itself an integral part of the period. Voters may recall fondly "Slippin' into Darkness," "The Cisco Kid," or "Why Can't We Be Friends?," but that will not be enough to push the band into the Hall.

Would I vote for the artist? No. Even though War did construct a cross-cultural sound even more effective for its spare but resonant impact, the band never developed a distinctive voice nor, beyond a few cogent songs, much to say in the first place. The high points in the War catalog are nearly obscured by the mass of middling efforts that make up the bulk of it.

Bill Withers

Background: Soul and R&B singer Bill Withers did not release his first album, Just As I Am (Sussex, 1971), until he was 32, having spent nine years in the US Navy before he pursued his musical career in earnest. His debut, produced by Booker T. Jones and with backing by most of the MGs and guitarist Stephen Stills, was indeed auspicious as the smoldering hit "Ain't No Sunshine," spotlighting Withers's relaxed yet assured voice, gave notice to an already-mature talent with songwriting insights exemplified by "Harlem" and especially with the winsome reminiscence of "Grandma's Hands," a childhood tale that has seen several cover versions, while his own covers of "Let It Be" and Fred Neil's "Everybody's Talkin'" revealed Withers's broad-ranging tastes. Still Bill (Sussex, 1972) confirmed that with the bluesy thump of "I Don't Want You on My Mind," the funky "Kissing My Love," the edgy, perceptive accusation of "Who Is He (And What Is He to You)," the percolating lust declaration of "Use Me," and especially the gospel-tinged invitation "Lean on Me," which topped the singles chart as it became Withers's signature song.Still Bill remains Withers's high-water mark. He cut one more album for Sussex before moving to Columbia Records and a slicker sound in the mid- to late 1970s that incorporated disco and a more pedestrian, anonymous approach—the cheerfully bland "Lovely Day" (1977), which was his first Top 40 hit since 1973's "Kissing My Love," exemplifies this trend. By the 1980s Withers was at the forefront of the Quiet Storm format, collaborating with saxophonist Grover Washington, Jr., on the near-chart-topper "Just the Two of Us," an admittedly infectious trifle that would go onto to haunt supermarkets and elevators for the rest of eternity. By 1985, Withers, having failed to chart with the album Watching You Watching Me, had ended his association with Columbia, and he has been effectively retired from the music business ever since.

Will the artist be voted into the Hall? No. Bill Withers had a brief heyday in the early 1970s as a distinctive soul singer, leaving behind a handful of classic singles but hardly enough to merit his inclusion on this year's ballot as anything more than a courtesy.

Would I vote for the artist? No. With a glory period that lasted only a few years, Bill Withers simply does not have the presence to justify a Hall of Fame vote. Moreover, despite an engaging, confessional lyrical manner that was unusual in black music at the time, Withers did not make an innovation significant enough to call him a pioneer.

Voting Summary

The table below summarizes the 15 nominees for 2015 by how I think the Hall voters will vote and by how I would vote were I eligible to do so.| 2015 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Nominees |

||||

| Nominee |

Hall Vote |

My Vote |

||

| Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

| The Paul Butterfield Blues Band |

X |

X |

||

| Chic |

X |

X |

||

| Green Day |

X |

X |

||

| Joan Jett and the Blackhearts |

X |

X |

||

| Kraftwerk |

X |

X |

||

| The Marvelettes |

X |

X |

||

| Nine Inch Nails |

X |

X |

||

| N.W.A. |

X |

X |

||

| Lou Reed |

X |

X |

||

| The Smiths |

X |

X |

||

| The Spinners |

X |

X |

||

| Sting |

X |

X |

||

| Stevie Ray Vaughan |

X |

X |

||

| War |

X |

X |

||

| Bill Withers |

X |

X |

||

| Totals |

6 |

9 |

7 |

8 |

I am a little more bullish on this year's nominees, being willing to cast one more "Yes" vote than how I think the Hall voters will do. My estimations of how the Hall voters will decide is purely a shot in the dark—as if I could hope to encapsulate what more than 500 voters will think—and it is based on their collective historical record. I will not elaborate further on the Hall's vote but I will summarize my own choices below.

This year's "deep historical period" is represented by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Marvelettes, and the Spinners, whose careers began in the 1960s. Although the first two seem to have champions on the nominating committee, neither is significant nor distinguished enough to merit inclusion in the Hall of Fame. The Spinners, on the other hand, have been long overdue for the Hall, perhaps not an obvious choice but still a well-qualified one.

Moving into the 1970s, Chic and Kraftwerk are the two acts whose heydays reside in that decade that deserve to be enshrined—although both get the nudge across the threshold because of their subsequent influence. Admittedly, each is a borderline pick, but the combination of each act's own catalog and the inspiration others drew from that catalog adds up to the Hall. Lou Reed is a Grand Old Man of rock, and given his longevity and influence he could be seen as a Hall of Famer, but his solo output was so wildly uneven that it is hard to justify his inclusion as an individual artist—he lacks any truly distinguishing characteristics. War and especially Bill Withers had their moments during the decade, but neither survived until the next decade, and even their glory periods in the 1970s are not strong enough to consider them as Hall of Fame material.

Of the acts whose careers peaked in the 1980s, only the Smiths have a body of work substantial and influential enough to justify a Hall vote. Sting made a modest splash in the 1980s, and he continues to record and tour, but his solo presence is not strong enough to earn him a spot in the Hall just for himself; he will have to settle for his current enshrinement as a member of the Police. Although I think that the Hall will vote for both Joan Jett and the Blackhearts and for Stevie Ray Vaughan, I do not think that either act makes a strong enough case to merit a place in the Hall. In Vaughan's case, his is a tragic one because of his premature death, but Jett has had three decades to wow us as something more than a high-energy jukebox, extolling someone else's emotion but not her own.

It may not be surprising that the three acts from the 1990s, Green Day, Nine Inch Nails, and N.W.A., are the strongest ones on the ballot. (I'm counting N.W.A. as a '90s act for its influence rather than actual career; the group was effectively sundered by 1991.) The Hall has had sufficient time to consider and elect many acts from previous years, and with a few exceptions noted here (Chic, Kraftwerk, the Spinners), it has done so. Green Day and Nine Inch Nails are in their first year of eligibility, and it would be surprising if either is not voted into the Hall this year as each is among the most recognizable and influential names of the past 25 years. N.W.A. is a tougher sell, but its recurrence on the ballot means that someone is fighting for it, and a vote for this influential hip-hop band is a valid one.

The Class of 2015 may not be one of the greatest in the history of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but given judicious selections by the Hall voters, it could be one of the stronger ones in recent years. If only I had a ballot of my own . . .

Comments powered by CComment