Index

The Struggle for Legacy

Watching a player struggle to reach a milestone can be painful. In recent memory, Tim Wakefield battled to reach the 200-win plateau in 2011. The knuckleballing right-hander won his 199th career game with the Boston Red Sox on July 24 with a 12–8 home-field victory over Ichiro Suzuki's Seattle Mariners although Wakefield in 6.1 innings surrendered 10 hits including a pair of home runs while allowing seven earned runs. Then Wakefield pitched seven more starts while pursuing that milestone 200th win.In 43 innings over those seven starts, Wakefield gave up 45 hits including seven home runs while allowing 33 runs, 25 of those earned, for a 4.79 ERA and a .259/.307/.454 opponents' slash line; he also walked 11 batters and hit three more although with that dancing knuckleball he did strike out 31. During that stretch, Wakefield lost three games while getting no decision in four starts as his win-loss record evened out to six wins and losses each; the Red Sox won two and lost five during his starts while losing another game, a 10–0 rout by the Texas Rangers, in which Wakefield pitched the final four innings as mop-up and did quite well, allowing no runs and only three hits while striking out three.

Wakefield finally notched his 200th win seven weeks later with a home-field victory over the Toronto Blue Jays on September 13, a wild one as the Red Sox trounced the Jays 18–6 although in six innings Wakefield allowed two home runs and five runs, all earned, while walking two batters and hitting one although he did strike out six hitters. Making two more starts to finish the 2011 season, Wakefield lost both of them and wound up with a sub-.500 record of 7–8. In the top ranks of Red Sox pitchers all-time in several categories, including first in innings pitched with 3006, Tim Wakefield will most likely be inducted into the team's Hall of Fame at some point. But although Wakefield is eligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame next year, he will be a one-and-done, and he would be even on a light ballot and not the overstuffed one it will be.

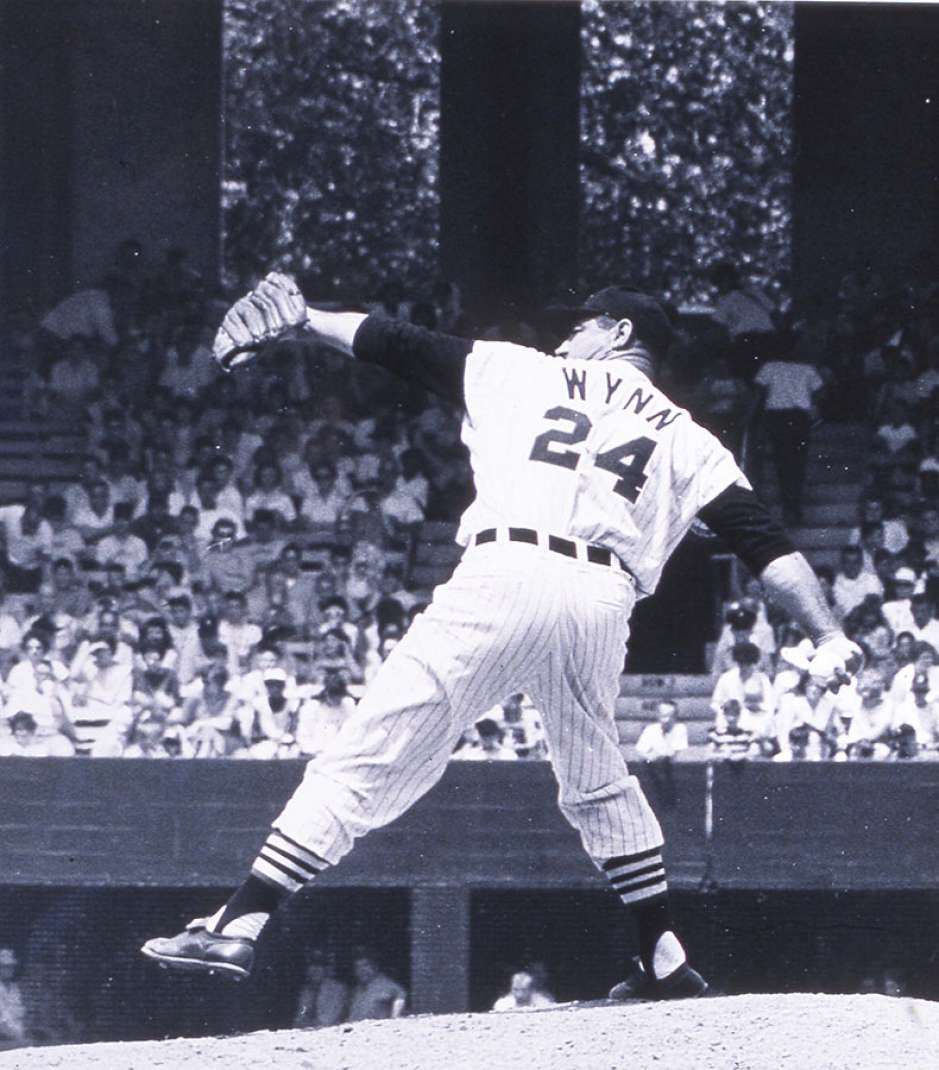

However, one pitcher who is in the Hall of Fame had an epic—and painful—struggle to reach the historic milestone of 300 wins. Early "Gus" Wynn labored to reach that 300th win. At the start of his penultimate season of 1962, the right-hander stood at 292 career wins; by the end of the season, having pitched for the Chicago White Sox, he had a 7–15 win-loss record for a .318 winning percentage. His ERA was 4.46, up nearly a run from the previous season. But most importantly, he was one win shy of 300 wins. Nevertheless, the White Sox, with no interest in a 42-year-old pitcher with gout whose fastball was gone, released him.

But Wynn, renowned as a battler, signed as a free agent in 1963 with the Cleveland Indians, for whom in nine seasons from 1949 to 1957 he had posted a 163–100 win-loss record with a 3.27 ERA and 118 ERA+, notching four seasons with 20 or more wins as part of a classic rotation that included future Hall of Famers Bob Feller and Bob Lemon. (ERA+ is a pitcher's earned run average adjusted for the league's ERA and park effects, and is indexed to 100, with 100 indicating a league-average pitcher.) Wynn did not sign with Cleveland until June 1963 and made his first appearance, a start, on June 21 against, fittingly enough, the White Sox. Although he lost, he pitched a complete game in a 2–0 shutout. His next two starts were both no-decisions even though the Indians ultimately won both games.

But on July 13, Wynn took the mound for the second game of a doubleheader in Kansas City against the Athletics. With the score tied at one-all in the top of the fifth inning, Wynn led off with a single and eventually scored as part of an Indians four-run frame that staked him to a lead. However, Wynn allowed three consecutive singles in the bottom half of the fifth, with all three runners scoring on a bases-clearing Jerry Lumpe double although Wynn caught a break when Lumpe was thrown out at third trying to stretch his drive into a triple. (One of the runners who scored had been pinch-runner Tony La Russa, who would ultimately go into the Hall of Fame as a manager.)

In the sixth, Wynn was lifted for a pinch-hitter, and Jerry Walker took over on the mound; Walker scattered three hits and worked around two walks without allowing any runs, earning the save in the Indians' eventual 7–4 victory—and Early Wynn's 300th career win. It wasn't pretty, with Wynn surrendering six hits including a home run as he walked three and allowed four runs, all earned, in five innings—and as Athletics third baseman Ed Charles recounted, Wynn was throwing nothing but "bloopers and junk," with a fastball that could not have topped 80 miles per hour.

Pitcher Early Wynn struggled his way to 300 wins--but did not feel proud about doing so. Will Ichiro Suzuki regret a similar slog to 3000 hits?

Wynn would go on to make 15 more appearances in 1963, including a start two weeks after winning his milestone game that saw him give up eight hits and two runs in 4.1 innings and that netted him a no-decision although Cleveland did win the game, while he was tagged with his final loss, his 244th, after pitching in relief on July 21 against the New York Yankees, who won in extra innings.

The Indians released Early Wynn after the 1963 season, and he appeared on his first Hall of Fame ballot in 1969, garnering just 27.9 percent of the vote despite becoming, at that time, only the 14th pitcher in Major League history to record 300 wins. However, he saw significant upticks in his next two appearances including 66.7 percent in 1971, and in the following year 76.0 percent of the voters elected Wynn to the Hall of Fame.

Early Wynn's career record of 300–244 (.551) and 3.54 ERA, which translates to an ERA+ of 107, is not that of an elite pitcher. He was just above league-average, which is not an insult but neither is it a Hall of Fame career. Was it the allure of 300 wins, which carried more weight 40-plus years ago, that nudged him into the Hall of Fame? Was he not a Hall of Famer at 299 wins? Tellingly, Wynn himself was not proud about hanging on to get that 300th win: "If I had pitched a good game and had gone nine innings, that would have been something. But that's not the way it was," Wynn was quoted as saying in a May 6, 1982, Warsaw, Indiana, Times-Union newspaper article.

The Struggle for Suzuki

The circumstances for Ichiro Suzuki may be completely different. Obviously, he is a hitter scrambling to amass 65 hits for the 3000-hit plateau and not a pitcher looking for a win. And this is a much different baseball environment than the one Wynn was in—an environment that is far more open about its business orientation. Do the Miami Marlins see baseball value in having Suzuki as a fourth outfielder? Is it business and public-relations value for them to have him collect his 3000th hit as a Marlin? Or will the Marlins, should Ichiro prove to be too big a liability, deem him unfit for their roster? And not to play to cultural stereotype, but would that move be considered by the Japanese Suzuki to be an unacceptable loss of face?Moreover, this current baseball environment relies less on the traditional counting numbers and more on qualitative measurements to evaluate excellence and legacy. This environment also recognizes that for a player such as Suzuki, his legacy as a 42-year-old player has already been written, and reaching a milestone such as 3000 hits may be a neat finish but is not necessary—and hanging on to pad the numbers is recognized as such.

Not that doing so is unknown—in fact, many Hall of Fame hitters have done so. We've seen that Al Kaline returned in 1974 to try for the 3000-hit plateau and, had he not reached it, how he would have returned in 1975 to try again. Another right fielder, Paul Waner, ended the 1940 season with 2868 hits, 132 hits shy of 3000—and with seven hits more than Kaline had had at the end of his 1973 season—when the Pittsburgh Pirates, the only Major League team he had played for, released him. He signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers for the 1941 season, but after hitting .171 for the Dodgers in 11 games and 45 plate appearances, they released him too. Two weeks later, Waner was playing for the Boston Braves, and he rallied somewhat with 82 hits and a .279 batting average although only 14 of those hits were for extra bases—and still he was 44 hits shy of 3000.

Waner returned to the Braves in 1942, and in 114 games and 404 plate appearances he did bang out 86 hits to cross the 3000-hit threshold; his slash line was .258/.376/.324, anemic in terms of batting average and slugging percentage—only 19 of his 86 hits were extra-base hits—although with 62 walks his on-base percentage was impressive. But although he had reached 3000 hits, Waner played on, returning to the Big Apple as a part-time player with Brooklyn in 1943 before they released him late in the 1944 season; Waner then signed with the Yankees for the remainder of the season; he was with the Yankees the following year, walking in his only plate appearance, before the Yankees released the 42-year-old former Pirates star.

Even after reaching 3000 hits in 1942, Waner likely stuck around because Major League jobs were available during World War Two as the talent pool had been thinned by the war effort; otherwise, Waner may never have reached the 3000 mark. Paul Waner is 17th in lifetime hits with 3152, and for his career he posted an elite .333/.404/.473 slash line with 605 doubles, 1627 runs scored, 1309 runs batted in, and 1091 walks against only 376 strikeouts. And although hindsight, again, is a luxury, had he retired after the 1940 season, his slash line would have been .340/.407/.490 with an OPS+ of 136 as opposed to his actual 134 OPS+. Those are not precipitous drops, and playing on not only pushed him over the 3000-hit line, it also netted him 600-plus doubles, 1600-plus runs scored, 1300-plus RBI, and nearly 1100 bases on balls—retiring after 1940 would have left him with 558 doubles, 1493 runs scored, 1177 RBI, and 909 walks.

Paul Waner was on five Hall of Fame ballots before gaining induction in 1952 with 83.3 percent of the vote. At the time of his retirement, he was only the seventh hitter to notch 3000 career hits. Of the other six, Ty Cobb (4191 hits) and Honus Wagner (3240) were in the inaugural Hall of Fame Class of 1936, Nap Lajoie (3243) and Tris Speaker (3514) followed them into the Hall in the next year, and Cap Anson (3435) was a Veterans Committee pick in 1939 while Eddie Collins (3315) was voted in by the writers that same year, his fourth time eligible. Nevertheless, the developing policies and erratic voting habits of the early ballots make it hard to form a cursory opinion of the results, and of why Waner needed five tries for the Hall.

And once in a great while an aging player does have a bounce-back final year. In 1959, 40-year-old Red Sox legend Ted Williams had suffered his worst year, posting a .254/.372/.419 slash line in 103 games and 331 plate appearance, which netted him just 69 hits including 10 home runs; it was the only time in his career that Williams had posted a sub-.300 batting average. In the previous year, he had slugged 26 homers and led the American League in batting average (.328) and on-base percentage (.458), but in 1959 it looked as if age had finally caught up with the Splendid Splinter.

But Williams soldiered on for another season—and he redeemed himself in splendid fashion. In 113 games and 390 plate appearances, he fell just two hits shy of 100 as he produced a robust .316/.451/.645 slash line while driving in 72 runs and slugging 29 long balls, which did push him over the 500 mark for career home runs. His final home run came in his last at-bat, at Boston's FenwayPark before the hometown crowd, a moment that had it appeared in a movie would be branded as contrived sentiment. (We'll leave opinion on The Natural for another time.)

Is Ichiro Suzuki the Real Mr. 3000?

And speaking of movies, will this year's Mr. 3000, Ichiro Suzuki, be able to script himself a triumphant exit that includes his reaching the 3000-hit circle? It is possible, although not likely, and it is more likely to be an embarrassing exit—it is 2016, not 1960, and the talent compression even in the National League is too high. Even if 2015 was an "adjustment year" to a new league, Ichiro is a luxury for the Miami Marlins in an environment in which luxuries are superfluous and cost more than they are worth, even if in current baseball financial terms Suzuki's one-year, $2 million contract is relative peanuts—Suzuki is taking up a valuable roster spot.Ichiro Suzuki could retire before the season starts, even before spring training starts, without having reached 3000 hits and still not diminish his legacy—he could even keep from tarnishing it with a sub-par performance. As I've noted previously, Suzuki is a borderline Hall of Famer, but his ten-year streak from 2001 to 2010 is a powerful argument, and, unfortunately, his continuing on only chips away at that argument.

Ichiro Suzuki's singular Hall of Fame legacy was established with the Seattle Mariners--does he really need to become "Mr. 3000" to guarantee that?

True, 3000 hits is a cherished hallmark, maybe even more so than in Paul Waner's day when it was even scarcer. But unlike the asinine premise of the sports comedy film Mr. 3000, a player is not automatically in or out of the Baseball Hall of Fame for falling on one side or the other of a neat and tidy milestone. Al Kaline managed to nudge past the 3000-hit mark but is just under three other thresholds. Early Wynn struggled to reach the 300-win threshold over the course of two seasons, a struggle that even he regretted, although he is not much different from the pitcher who had begun the 1962 season with eight fewer wins—Wynn's legacy had been written already.

Ichiro Suzuki will not be any more of a Hall of Fame player for reaching 3000 hits, and he will not be any less of a Hall of Famer for not doing so. But if has another season as he did in 2015, costing the Marlins just over a full win above a replacement player, it could be hard for the Marlins not to replace him. Contemporary baseball has little room for sentiment. Ichiro Suzuki may be the real Mr. 3000 now, but he has no need to be.

« Prev Next

Comments powered by CComment