Index

Batter up! For 2016, the Pre-Integration Era Committee is at the plate for Baseball Hall of Fame evaluations and inductions not being done by the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA). The Pre-Integration Era covers the period from 1876, when the National League was formed, to 1946, the last year before Major League Baseball became integrated with the introduction of African-American players Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby into, respectively, the National League and American League.

The Pre-Integration Era Committee is currently one of three committees functioning as an overall unit to evaluate players and non-players from baseball's past who may have been overlooked in previous evaluations for the Hall of Fame. Those evaluations may have been done for players both by the BBWAA, which gets first crack at evaluating retired players for enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame, and by previous post-writers committees that are historically and collectively known as the veterans committee, which has existed in various forms ever since Hall of Fame selections have been made; this current unit is the latest incarnation of the veterans committee, although the term "veterans committee" is no longer officially recognized. In addition, these post-BBWAA committees also evaluate non-players—umpires, managers, executives, and pioneers—for Hall of Fame enshrinement.

Joining the Pre-Integration Committee are the Golden Era Committee, which covers the years 1947 to 1972, and the Expansion Era Committee, which covers from 1973 to the present. Since 2010, when all three committees were formed, each committee comes up to bat every three years. The Pre-Integration Committee first convened in 2012, with its selections slated for induction in 2013, and it voted three candidates into the Hall of Fame: umpire Hank O'Day, executive Jacob Ruppert, and player Deacon White.

One irony in the 2013 voting was its relation to the 2013 writers' vote, which on a ballot overstuffed with qualified Hall of Fame players did not elect a single candidate to the Hall, leaving White, who had last played a baseball game in 1890, as the only player to be inducted that year. And as a sardonic comment on the ongoing furor over recent players who may have "cheated" by using performance-enhancing drugs, James "Deacon" White was in reality a church deacon and a non-smoking, Bible-toting baseball player, a rarity in rough-and-tumble 19th-century baseball—as was his belief that the Earth was flat—whose supposed clean living stood as a rebuke to the PEDs-abusing current candidates.

To be fair, the Pre-Integration Era Committee's 2013 selections were not necessarily unjustified, and its fellow committees have also made judicious selections. For example, the Golden Era Committee in 2011 elected third baseman Ron Santo to the Hall of Fame, thus correcting a long-decried oversight, while in 2013 the Expansion Era Committee voted managers Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa, and Joe Torre (whose playing career was of near-Hall of Fame quality) into the 2014 Hall of Fame class.

However, last year's Golden Era Committee did not elect a single candidate to the Hall of Fame, this despite a number of players whose candidacies had been vigorously championed for many years, including Dick Allen, Gil Hodges, Minnie Miñoso, and Luis Tiant. I examined that ballot in detail, and I concluded that although a few players are truly on the threshold of the Hall of Fame—Allen, Tiant, and maybe Miñoso—none were ultimately oversights that needed to be corrected.

This prompts the question for this year's Pre-Integration Era Committee: Are there any Hall of Famers left from this period? This question becomes more salient because the period covered by the committee, 1876 to 1946, has been examined for decades. In fact, the stated purpose of the earliest veterans committees was to ensure that players from previous eras were not overlooked by voters who might not have experience or even knowledge of players from the 19th century or early 20th century who deserve to be recognized as among the greatest of all time.

On the other hand, the various incarnations of the veterans committee have also made many of the most marginal, even dubious, selections for the Hall of Fame. One notorious incarnation occurred under the watch of Frankie Frisch, a star second baseman nicknamed the "Fordham Flash" whom the writers inducted in 1947, but who as the veterans committee chairman in the late 1960s and early 1970s oversaw the induction of some of the least-qualified players in the Hall including pitchers Jesse Haines and Rube Marquard and fielders Travis Jackson and George "High Pockets" Kelly; many of these players were former Frisch teammates.

So, as we now turn to examining the Pre-Integration Era Committee ballot for 2016, the results of which are to be announced on December 7, 2015, the question remains: Are there any Pre-Integration Era candidates worthy of the Baseball Hall of Fame?

The 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot

This year's Pre-Integration Era Committee has ten candidates to consider, six players, three executives, and one pioneer. The six players are Bill Dahlen, Wes Ferrell, Marty Marion, Frank McCormick, Harry Stovey, and Bucky Walters. The three executives are Sam Breadon, Garry Hermann, and Chris von der Ahe. The sole pioneer is Doc Adams.Four of the six players had been on the previous Pre-Integration Era ballot for 2013. Dahlen had been the top vote-getter among players not elected, with 10 of the 16 votes (Deacon White was the sole player elected for 2013), while Ferrell, Marion, and Walters each received three or fewer votes. Breadon was also on the previous ballot, receiving three or fewer votes.

Five of the six players have appeared on at least one BBWAA ballot, which is notable because this group spans a broad expanse of baseball history. Stovey was a 19th-century player exclusively, playing from 1881 to 1893, and for eight of his 14-year playing career he played in leagues that have not existed for more than a century—seven years in the American Association League and one year in the Players' League. Dahlen straddled two centuries, starting in 1891 in the 19th century and ending in 1911 in the 20th century.

And while Dahlen and Stovey were pure products of the Dead-ball Period, the other four played exclusively in the Live-ball Period: Ferrell had the earliest start, beginning his 15-year career in 1927; Walters played his first Major League game in 1931, McCormick played his in 1934, and both wrapped up their careers just as the Integration Era began, while Marion straddled the Pre-Integration and Integration Eras, starting his career in 1940 season and ending it in 1953.

The wide historical span as well as the changing rules and practices of both the BBWAA and the veterans committees make any comparison difficult if not simply meaningless. Thus the following table summarizes five of the six players' voting records based on BBWAA balloting. (Harry Stovey has never appeared on a BBWAA ballot.) It lists their first appearance on a BBWAA ballot; the number of years they were on a ballot; the percentage of the vote they received in the first year and the final year on a ballot; and the highest percentage of the vote they received during their entire run on a ballot.

| 2016 Pre-Integration Era Candidates, BBWAA Voting Summary |

||||||

| Player |

First Appearance |

Years on Ballot |

Debut Percentage |

Ending Percentage |

Highest Percentage |

|

| Bill Dahlen |

1936 |

1 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

| Wes Ferrell |

1948 |

6 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

3.6 |

|

| Marty Marion |

1956 |

12 |

0.5 |

33.4 |

40.0 |

|

| * Frank McCormick |

1956 |

4 |

1.6 |

1.1 |

3.0 |

|

| Bucky Walters |

1950 |

13 |

2.4 |

9.7 |

23.7 |

|

Dahlen appeared on the very first writers' ballot in 1936, while Stovey was one of those players whom the veterans committee was worried would be forgotten or overlooked by the writers; Stovey did appear on the first veterans committee ballot in 1936 and received 7.7 percent of the vote. All six players have been considered at least for nomination at some point by an incarnation of the veterans committee, although the various approaches tried by different incarnations of the veterans committee does not help to determine whether any of these players are actually Hall of Famers.

At the 2015 Winter Meetings, the 16-member Pre-Integration Era Committee will meet to vote on the slate of ten candidates. The committee comprises four Hall of Fame members (Bert Blyleven, Bobby Cox, Pat Gillick, and Phil Niekro), four executives (Chuck Armstrong, Bill DeWitt, Gary Hughes, and Tal Smith), and eight media figures and historians (Steve Hirdt, Peter Morris, Jack O'Connell, Claire Smith, Tim Sullivan, T.R. Sullivan, Gary Thorne, and Tim Wendel). Half of the current committee—Blyleven, DeWitt, Gillick, Hirdt, Hughes, Morris, Smith, and T.R. Sullivan—had served on the committee that elected the 2013 inductees.

And just as that committee will be doing, let's do an in-depth examination of all ten candidates on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era ballot.

The 2016 Pre-Integration Era Player Candidates

There are a number of challenges in evaluating players from the Pre-Integration Era, from 1876 to 1946. First, the era spans seven decades—the first half of Major League Baseball's long history—and includes baseball at various stages of its development, often radically so: 19th-century baseball is in several respects unrecognizable compared to the modern game. Thus, it is tricky, to say the least, to compare a 19th-century player to a modern-era player (from 1901 onward) because each was playing a fundamentally different game. It is always tricky to compare players across different eras in any case, but more so for players who played before the modern era when there were significant differences regarding foul balls, fly balls, balks, stolen bases—even the distance between the pitcher's mound and home plate.Next, the evidence we have of players up to the early 20th century is fragmentary compared to that of players from later eras. There is no one alive now who saw Harry Stovey play baseball—Stovey's final season was in 1893. There most likely is not anyone alive who saw Bill Dahlen play even in his final season in 1911 (and there are precious few persons still alive who were even born in 1911). All we have to go on are their playing records and accounts written at the time and evaluations developed subsequently, which contain the biases and limitations of their times and of subsequent times, as perceptions change over time.

Finally, the legacy of the earliest players was a concern in 1936, when the first Hall of Fame voting took place. From that point on, various veterans committees engaged in determining whether players from bygone eras were Hall of Famers—at times with a zealousness that resulted in several marginal players being enshrined in the Hall; significantly, it has been the veterans committees and not the BBWAA voters that have selected the weakest Hall of Famers. In other words, all six players have been examined a number of times previously by various veterans committees, while four of them—Wes Ferrell, Marty Marion, Frank McCormick, and Bucky Walters—have been examined by BBWAA voters on more than one ballot.

So, are there any Hall of Famers left in the Pre-Integration Era? Let's find out.

Here are the four position players on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era ballot, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it and explained below the table.

| Position Players on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Dahlen, Bill |

.272/.358/.382 |

.357 |

75.2 |

77.5 |

110 |

108 |

| Stovey, Harry |

.289/.361/.461 |

.380 |

45.1 |

54.9 |

144 |

132 |

| McCormick, Frank |

.299/.348/.434 |

.363 |

34.8 |

33.3 |

118 |

118 |

| Marion, Marty |

.247/.320/.339 |

.317 |

31.6 |

30.0 |

81 |

83 |

wOBA: Weighted on-base average as calculated by FanGraphs. Weighs singles, extra-base hits, walks, and hits by pitch; generally, .400 is excellent and .320 is league-average.

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

OPS+: Career on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 OPS+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

wRC+: Career weighted Runs Created, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 wRC+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

Here are the two pitchers on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era ballot, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it and explained below the table.

| Pitchers on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Pitcher |

W-L (S), ERA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

ERA+ |

ERA– |

FIP– |

| Ferrell, Wes |

193–128 (13), 4.04 |

61.6 |

50.8 |

116 |

87 |

93 |

| Walters, Bucky |

198–160 (4), 3.30 |

54.2 |

34.5 |

116 |

87 |

99 |

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

ERA+: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA+ indicating a league-average pitcher, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

ERA–: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA- indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

FIP–: Fielding-independent pitching, a pitcher's ERA with his fielders' impact factored out, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 FIP– indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

An important note regarding both Wes Ferrell and Bucky Walters is that their WAR values, both from FanGraphs and especially from Baseball Reference, are significantly impacted by their hitting records. For bWAR, Ferrell derives a staggering 12.8 wins from his offensive value, and for fWAR it is a comparable 12.2 wins. Walters derives a significant 7.8 wins from his hitting for bWAR although for fWAR his offense is actually a liability at a –2.3 wins. We will examine this fascinating anomaly in greater detail below.

The table below combines both position players and pitchers into a ranking by bWAR with their fWAR values also listed.

| All 2016 Pre-Integration Era Candidates, Ranked by bWAR |

|||

| Rank |

Player |

bWAR |

fWAR |

| 1 |

Dahlen, Bill |

75.2 |

77.5 |

| 2 |

Ferrell, Wes |

61.6 |

50.8 |

| 3 |

Walters, Bucky |

54.2 |

34.5 |

| 4 |

Stovey, Harry |

45.1 |

54.9 |

| 5 |

McCormick, Frank |

34.8 |

33.3 |

| 6 |

Marion, Marty |

31.6 |

30.0 |

According to bWAR, and using 60.0 WAR as a rough baseline for serious consideration for the Hall of Fame, only Bill Dahlen and Wes Ferrell are worthy of serious discussion, with Bucky Walters on the threshold and worthy of some discussion. Does a ranking by fWAR change the criterion for discussion?

The table below combines both position players and pitchers into a ranking by fWAR with their bWAR values also listed.

| All 2016 Pre-Integration Era Candidates, Ranked by fWAR |

|||

| Rank |

Player |

fWAR |

bWAR |

| 1 |

Dahlen, Bill |

77.5 |

75.2 |

| 2 |

Stovey, Harry |

54.9 |

45.1 |

| 3 |

Ferrell, Wes |

50.8 |

61.6 |

| 4 |

Walters, Bucky |

34.5 |

54.2 |

| 5 |

McCormick, Frank |

33.3 |

34.8 |

| 6 |

Marion, Marty |

30.0 |

31.6 |

Even if ranked by fWAR, not much really changes in this sample. Dahlen remains at the top by a substantial margin while Ferrell and Stovey move onto the "bubble," into that region in which they might merit discussion for the Hall based on other criteria. Otherwise, no one else merits serious discussion.

And even though WAR is becoming commonplace regardless of which version is cited, it is not the only criterion for evaluation. Furthermore, it is a measure of a player's value that is helped in part by the longevity of a player's career—the longer a player plays, the more opportunities he has to be valuable to his team. Of course, if a player is playing for a long time, it may indicate that he does indeed have value to his team and does not need to be replaced, although all six player candidates played in periods of talent dispersion—there were a few great players in a pool of many mediocre ones—and thus even a player whose skills had eroded significantly was less likely to be replaced. Moreover, their WAR values are likely inflated because of the paucity of overall talent.

Nevertheless, WAR does measure the performance that contributes to that value, and both in a positive and negative manner; in other words, a player whose performance detracts from his team's ability to win is measured as a negative value. And sabermetrician Jay Jaffe has developed "JAWS," the Jaffe WAR Score system, to compare a player at a position against all players, in aggregate, who are already in the Hall at that position by using their WAR values. Note that Jaffe's system uses the Baseball Reference version of WAR, and the usual caveats about the limitations of WAR apply.

The JAWS rating itself is an average of a player's career WAR and his seven-year WAR peak. Jaffe also assigns one position to a player who may have played at more than one position, choosing the position at which the player contributed the most value. The purpose of JAWS is to improve, or at least maintain, the current Hall of Fame standards at each position to ensure that only players at least as good as average current Hall of Famers are selected for the Hall.

The table below lists all six players on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era ballot, ranked by JAWS, along with other JAWS statistics, which are explained below the table, as well as the average bWAR and JAWS statistics for all Hall of Fame players at that position. The table also contains the players' ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards, also explained below the table.

| All 2016 Pre-Integration Era Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Players (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player |

Pos. |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

Ave. HoF bWAR |

Ave. HoF JAWS |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Ferrell, Wes |

SP |

61.6 |

55.0 |

58.3 |

39 |

73.9 |

62.1 |

75 |

33* |

| Dahlen, Bill |

SS |

75.2 |

40.1 |

57.7 |

10 |

66.7 |

54.7 |

94 |

48 |

| Walters, Bucky |

SP |

54.2 |

43.0 |

48.6 |

77 |

73.9 |

62.1 |

104 |

28** |

| Stovey, Harry |

LF |

45.1 |

31.1 |

38.1 |

37 |

65.1 |

53.3 |

86 |

34 |

| McCormick, Frank |

1B |

34.8 |

28.3 |

31.6 |

57 |

65.9 |

54.2 |

86 |

18 |

| Marion, Marty |

SS |

31.6 |

26.2 |

28.9 |

63 |

66.7 |

54.7 |

57 |

17 |

** Walters's index comprises values of 27 for his pitching record and 1 for his hitting record.

Pos.: Player's position under evaluation in this table.

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

WAR7: The sum of a player's best seven seasons as defined by bWAR; they need not be consecutive seasons.

JAWS: Jaffe WAR Score system—an average of a player's career WAR and his seven-year WAR peak.

JAWS Rank: The player's ranking at that position by JAWS rating.

Ave. HoF bWAR: The average bWAR value of all the Hall of Famers at that position.

Ave. HoF JAWS: The average JAWS rating of all the Hall of Famers at that position.

Hall of Fame Monitor: An index of how likely a player is to be inducted to the Hall of Fame based on his entire playing record (offensive, defensive, awards, position played, postseason success), with an index score of 100 being a good possibility and 130 a "virtual cinch." Developed by Baseball Reference from a creation by Bill James.

Hall of Fame Standards: An index of performance standards, indexed to 50 as being the score for an average Hall of Famer. Developed by Baseball Reference from a creation by Bill James.

Based solely on JAWS rankings, Bill Dahlen, ranked by JAWS as the tenth-best shortstop in baseball history, looks to be a criminally overlooked case. This is the conclusion reached by the Nineteenth Century Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) when it named Dahlen its Overlooked 19th-Century Baseball Legend for 2012. Of the top 15 shortstops as determined by JAWS who are currently eligible for the Hall of Fame, the only other candidate not already in the Hall of Fame is Alan Trammell, ranked just one spot below Dahlen—and Trammell's travails on the BBWAA ballot end this year one way or another as it is his final year on the writers' ballot.

(The other two shortstops in the top 15 not currently eligible for the Hall of Fame are Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez. Barring a revelation that Jeter is a mad rapist or a serial killer, he is certain to be elected in his first year of eligibility in 2020. Rodriguez, alas, will wish that he were merely Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens with respect to performance-enhancing drugs: It is entirely possible that his Hall of Fame induction will be a posthumous one, long after everyone has forgotten why PEDs was such a contentious issue. It will certainly remain a contentious issue when Rodriguez, owner of the longest suspension for violating Major League Baseball drug policy, among other transgressions, becomes eligible for his first Hall of Fame ballot.)

But apart from Dahlen, none of the other player candidates seem overlooked according to JAWS rankings. However, Wes Ferrell is an intriguing case: He is ranked 39th among starting pitchers; there are 62 pitchers enshrined in the Hall of Fame, and considering the high number of marginal pitchers already in the Hall of Fame (along with the aforementioned Haines and Marquard, Chief Bender, Herb Pennock, Catfish Hunter, and Lefty Gomez, among others, are dubious picks), is Ferrell truly an overlooked Hall of Famer? As noted above, a significant portion of Ferrell's value derives from his offensive prowess—stripped of that, Ferrell does not look like a Hall of Fame pitcher. But are we being too narrowly focused? We'll have to explore this below.

As we did last year with the Golden Era candidates, let's examine this year's Pre-Integration Era candidates as they compare to their contemporaries already in the Hall of Fame. However, because the Pre-Integration Era is significantly longer than the Golden Era, almost three times longer, and because it comprises three broadly distinct periods—19th-century baseball, 20th-century "modern game" (since 1901) dead ball (from 1901 to 1920), and 20th-century "modern game" live ball (from 1921 to 1946)—it is only fair to make the comparisons equitable. And as we did last year, let's also make the comparisons against players at the same position, or at least at the candidates' primary position.

Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame First Baseman: 20th Century Live Ball

The only first baseman on the Pre-Integration Era ballot this year is Frank McCormick, who played primarily for the Cincinnati Reds and spent his entire 13-year career in the National League. McCormick came up for a cup of coffee with the Reds in 1934 before spending the next two seasons in the minor leagues. He saw limited action with the parent club in 1937 before becoming a full-time player for the Reds the following season, and after an auspicious start—he led the National League in hits for three consecutive years between 1938 and 1940—McCormick was a lineup fixture until 1946; he retired two seasons later.The table below includes the five Hall of Fame first basemen from the live-ball period of the Pre-Integration Era whose career timelines overlap with McCormick's to some degree, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

To bolster an admittedly small sample, I've included Rudy York, who is not in the Hall of Fame or a candidate on this ballot; however, in a coincidence too timely to pass up, York's career timeline is identical to McCormick's (1934 to 1948) while York is ranked immediately behind McCormick on the JAWS listing for first basemen.

| Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) Hall of Fame First Basemen and 2016 First Basemen Candidate on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Gehrig, Lou |

.340/.447/.632 |

.477 |

112.4 |

116.3 |

179 |

173 |

| Foxx, Jimmie |

.325/.428/.609 |

.460 |

96.4 |

101.8 |

163 |

158 |

| Mize, Johnny |

.312/.397/.562 |

.433 |

71.0 |

68.6 |

158 |

157 |

| Greenberg, Hank |

.313/.412/.605 |

.453 |

57.5 |

61.1 |

158 |

154 |

| Bottomley, Jim |

.310/.369/.500 |

.393 |

35.3 |

37.7 |

125 |

124 |

| McCormick, Frank |

.299/.348/.434 |

.363 |

34.8 |

33.3 |

118 |

118 |

| * York, Rudy |

.275/.362/.483 |

.390 |

34.7 |

39.1 |

123 |

122 |

The table below lists these five Hall of Fame first basemen associated with the live-ball period of the Pre-Integration Era along with McCormick and York, ranked by JAWS, along with other JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all first basemen in the Hall of Fame.

| 2016 Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) First Baseman Candidate, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame First Basemen (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Gehrig, Lou |

17 |

1923 |

1939 |

112.4 |

67.7 |

90.0 |

1 |

352 |

72 |

| Foxx, Jimmie |

20 |

1925 |

1945 |

96.4 |

59.4 |

77.9 |

3 |

314 |

72 |

| Mize, Johnny |

15 |

1936 |

1953 |

71.0 |

48.8 |

59.9 |

8 |

175 |

47 |

| Ave of 19 HoF 1B |

NA |

NA |

NA |

65.9 |

42.4 |

54.2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Greenberg, Hank |

13 |

1930 |

1947 |

57.5 |

47.7 |

52.6 |

16 |

188 |

46 |

| Bottomley, Jim |

16 |

1922 |

1937 |

35.3 |

28.8 |

32.0 |

55 |

99 |

42 |

| McCormick, Frank |

13 |

1934 |

1948 |

34.8 |

28.3 |

31.6 |

57 |

86 |

18 |

| * York, Rudy |

13 |

1934 |

1948 |

34.7 |

28.4 |

31.5 |

58 |

68 |

28 |

Admittedly, four of the Hall of Fame first basemen from McCormick's playing period—Gehrig, Foxx, Mize, and Greenberg—are among the best ever to play the game; on the other hand, we are evaluating legacy to determine whether McCormick is among the best-ever, aren't we?

Tellingly, the fifth Hall of Fame first baseman from this period, Jim Bottomley, had been elected to the Hall in 1974 by a veterans committee chaired by Frankie Frisch, who had been accused of fostering cronyism in the committee's selections—and it is no surprise that Bottomley and Frisch had been teammates on the St. Louis Cardinals. But although Bottomley's credentials for the Hall of Fame are marginal at best, they are still better than McCormick's.

Frank McCormick's career got off to an auspicious start, and he had a fine career capped by being named the National League's Most Valuable Player in 1940 and by being named to eight NL All-Star teams, with seven of those appointments consecutive ones from 1938 to 1944. (In 1945, there was no All-Star Game held because of wartime travel restrictions, and no players were officially selected that year; McCormick had been selected to the NL All-Star squad in 1946, his last year as an All-Star.) He led the NL in hits three years in a row, establishing his career-high single-season total of 209 hits in 1938 and matching that in 1939, and he had seasons with 150 or more hits five other times.

During that seven-year period from 1938 to 1944, when he had been named as an All-Star, McCormick posted a .304/.351/.451 slash line, averaging each season 178 hits, 35 doubles, 14 home runs, 80 runs scored, and 101 runs batted in; his OPS+ during this period was 122, and his seasonal bWAR was 4.0—strong for a starting player but below the minimum of 5.0 typically expected of All-Star-caliber players; he did generate seasonal bWARs above 5.0 in 1939, 1940, and 1944, that last year containing his career-high of 6.1. (During McCormick's playing career, the Wins Above Replacement statistic did not exist; it has been applied retrospectively.)

McCormick did have four seasons in which he finished in the top ten for NL Most Valuable Player voting, and he won the award in 1940 when he led the League in hits (191) and doubles (44) while posting a .309/.367/.482 slash line with 19 home runs, 93 runs scored, and 127 RBI, one shy of his career-high from the previous year, when he led the NL in RBI; all told, he had four seasons with 100 or more RBI.

Doubtless McCormick's excellent performance was a crucial factor in leading his Cincinnati Reds to the National League pennant in 1940; the Reds then defeated the Detroit Tigers in seven games to become World Series champions. However, McCormick's MVP award has been criticized over the years, with the critical consensus being that fellow first baseman Johnny Mize of the St. Louis Cardinals deserved the award.

In 1940, Mize led the NL in home runs (43) and RBI (137) as he put up a robust .313/.404/.636 slash line; retrospectively, Mize also led the League in overall bWAR with 7.4 (McCormick was sixth with 5.7), offensive bWAR with 7.7 (McCormick was eighth with 4.4), and OPS+ with 177 (McCormick's 132 did not make the top ten). Alas, the Cardinals placed third in the NL standings, 16 games behind the Reds although St. Louis nevertheless won 84 games. McCormick also played during the war years—the United States was officially at war from 1942 to 1945—when the talent pool was depleted by the absence of many Major League players serving in the military; those included Mize, who spent three years, from 1943 to 1945, in the US Navy during the prime of his career.

A solid first baseman with a fine career, Frank McCormick is not an exceptional candidate, and his has not been overlooked previously. He is not a Hall of Fame player.

Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame Shortstop: Dead Ball

Although there are two shortstops on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era ballot, Bill Dahlen and Marty Marion, each played in fundamentally different periods—Dahlen straddled the 19th and 20th centuries as he played exclusively with the dead ball, while Marion played exclusively with the live ball. Thus, it would be inaccurate, if not unfair, to compare them directly.So, let's start with Dahlen first. Here are the five Hall of Fame shortstops associated with the Pre-Integration Era (Dead Ball) whose careers overlapped Dahlen's to some degree, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Pre-Integration Era (Dead Ball) Hall of Fame Shortstops and 2016 Shortstop Candidate on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Wagner, Honus |

.328/.391/.467 |

.408 |

131.0 |

138.1 |

151 |

147 |

| Davis, George |

.295/.362/.405 |

.366 |

84.7 |

84.6 |

121 |

118 |

| Dahlen, Bill |

.272/.358/.382 |

.357 |

75.2 |

77.5 |

110 |

108 |

| Wallace, Bobby |

.268/.332/.358 |

.333 |

70.2 |

62.4 |

105 |

104 |

| Tinker, Joe |

.262/.308/.353 |

.319 |

53.2 |

55.5 |

96 |

96 |

| Jennings, Hughie |

.312/.391/.406 |

.385 |

42.3 |

44.9 |

118 |

119 |

The table below lists these five Hall of Fame shortstops associated with the Pre-Integration Era (Dead Ball) and Dahlen, ranked by JAWS, along with other JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all shortstops in the Hall of Fame.

| Pre-Integration Era (Dead Ball) 2016 Shortstop Candidate, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Shortstops (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Wagner, Honus |

21 |

1897 |

1917 |

131.0 |

65.4 |

98.2 |

1 |

312 |

75 |

| Davis, George |

20 |

1890 |

1909 |

84.7 |

44.3 |

64.5 |

4 |

81 |

54 |

| Dahlen, Bill |

21 |

1891 |

1911 |

75.2 |

40.1 |

57.7 |

10 |

94 |

48 |

| Wallace, Bobby |

25 |

1894 |

1918 |

70.2 |

41.8 |

56.0 |

14 |

30 |

30 |

| Ave of 21 HoF SS |

NA |

NA |

NA |

66.7 |

42.8 |

54.7 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Tinker, Joe |

15 |

1902 |

1916 |

53.2 |

33.1 |

43.2 |

24 |

24 |

20 |

| Jennings, Hughie |

18 |

1891 |

1918 |

42.3 |

39.0 |

40.6 |

28 |

88 |

34 |

In this sample, Bill Dahlen ranks third, behind Honus Wagner and George Davis. The difference between Wagner and Davis is an interesting gulf. Wagner was one of the first five players ever inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936, ahead of even Cy Young, who had won an amazing 511 games as a pitcher and whose name would later be used on the award that honors the best pitcher in each league. (Young was inducted the next year.) Wagner tied with Babe Ruth for the second-highest vote total; then, more than sixty years later, Wagner was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team in 1999, albeit one of five chosen by a select panel as opposed to having been voted onto the team by fan balloting.

Davis, by contrast, fell into obscurity as soon as he stopped playing baseball. He appears in no official records by either the BBWAA or the veterans committee concerning voting. Davis's statistics had always been part of the baseball record, but no one really paid any mind to them, at least within the last two decades, until Bill James in his book about the Hall of Fame declared Davis to be the best player not inducted into the Hall. Two years later, other baseball researchers including John Thorn and Pete Palmer, co-authors of the official baseball encyclopedia Total Baseball, took up the cry, and by 1998 the veterans committee had elected Davis.

Dahlen may be just behind Davis, but in terms of value he is ahead of Bobby Wallace, Joe Tinker, and Hughie Jennings, shortstops roughly from Dahlen's time period who had all been inducted into the Hall between the 1940s and 1950s.

Defensively, Dahlen remains among distinguished company. The table below lists the Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame shortstops from the dead-ball period and Dahlen, ranked by dWAR, or Wins Above Replacement based on defensive value only, with other defensive metrics (explained below the table) and their career stolen base totals.

| Defensive and Stolen-Base Statistics for Pre-Integration Era (Dead Ball) Hall of Fame Shortstops and 2016 Shortstop Candidate on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by dWAR |

|||||||||

| Player |

Putouts |

Assists |

Double Plays Turned |

Total Zone |

dWAR |

Fld. Pct. |

RF/9 |

League RF/9 |

Stolen Bases |

| Tinker, Joe |

3768 |

5856 |

671 |

180 |

34.3 |

.938 |

5.63 |

5.40 |

336 |

| Wallace, Bobby |

4142 |

6303 |

640 |

105 |

28.7 |

.938 |

5.89 |

5.61 |

201 |

| Dahlen, Bill |

4856 |

7505 |

881 |

120 |

28.4 |

.927 |

5.96 |

5.67 |

548 |

| Davis, George |

3239 |

4794 |

590 |

106 |

24.0 |

.940 |

6.04 |

5.74 |

619 |

| Wagner, Honus |

4576 |

6041 |

766 |

67 |

21.3 |

.940 |

5.67 |

5.43 |

723 |

| Jennings, Hughie |

2384 |

3143 |

411 |

56 |

9.0 |

.922 |

6.37 |

5.77 |

359 |

dWAR: Wins Above Replacement for defensive play only, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Note that this value is an aggregate value and includes value generated at positions other than shortstop.

Fld. Pct: Fielding percentage, defined as total putouts plus total assists divided by total chances (total putouts, total assists, total errors).

RF/9: Range factor per nine innings, defined as total putouts plus total assists multiplied by 9, and then divided by the total innings played.

League RF/9: Range factor per nine innings, defined as total putouts plus total assists multiplied by 9, and then divided by the total innings played, computed for the entire league.

In terms of dWAR (again, a statistic that did not exist in Dahlen's day), Dahlen is ahead of Davis and Wagner, while he is second only to Tinker in total runs saved above a league-average shortstop. And if Dahlen is second all-time among shortstops in errors committed, contributing to his relatively low fielding percentage, he is also second in putouts and fourth in assists. Dahlen's range factor is also above the league average.

Offensively, for a 13-year period from 1892 to 1904, Dahlen produced a .287/.371/.410 slash line, averaging each season 139 hits including 24 doubles, 11 triples, and 5 home runs while scoring 95 runs and driving in 72 as he swiped 35 bases. Dahlen's 2461 hits ranks 107th all-time, his 413 doubles 158th, and his 163 triples, coincidentally tied with Davis, ranks 33rd, while his 1590 runs scored is 50th best as his 548 stolen bases are 28th all-time. In addition, Dahlen's 1234 RBI is 140th all-time, which remains impressive for a middle infielder of his era.

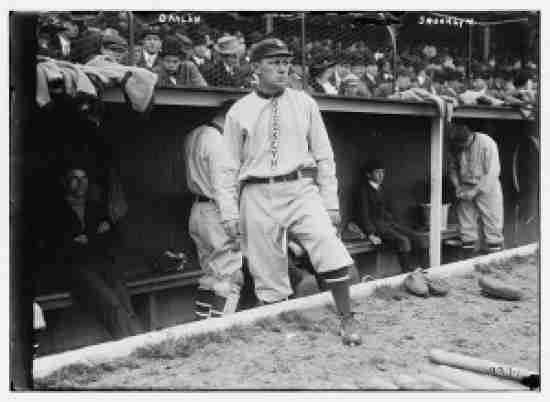

At the tail-end of his playing career, Bill Dahlen became manager of the Brooklyn franchise, known as either the Dodgers or the Superbas depending on which year it was, although it should be noted that the team's nickname was not an official designation at least until 1932, when the name "Dodgers" first appeared on the team's uniforms. Dahlen had inherited a weak club, and he was unable to do much except keep the team out of the cellar for the four years that he managed from 1910 to 1913. However, his ferocious temper, vented at various umpires, cemented his own nickname of "Bad Bill," and he is still among the top ten managers all-time with 65 ejections.

"Bad Bill" Dahlen looks ready to tussle with the umpire and possibly receive one of his 65 ejections.

As a shortstop during a time when baseball transitioned from the 19th-century game to the modern game, and during a time when middle infielders were not expected to be offensive threats, Bill Dahlen was an outstanding two-way player, a slugging shortstop who could steal bases and was a reliable glove at a crucial defensive position. And as a 35-year-old shortstop in 1905, Dahlen helped the then-New York Giants to their first World Series championship.

Frankly, there are very few players from the Pre-Integration Era who have been overlooked with respect to inclusion in the Baseball Hall of Fame. However, Bill Dahlen is legitimately one of them—he is clearly equivalent to his contemporaries already in the Hall, and in terms of bWAR and JAWS he is above the threshold formed by the aggregated records of all shortstops in the Hall. Dahlen just missed election on his last ballot for the 2013 induction—that honor going to Deacon White instead—and this year is the opportunity to correct that oversight. Bill Dahlen is a Hall of Famer.

Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame Shortstop: Live Ball

On the other hand, Marty Marion has not been overlooked—he had appeared on 12 BBWAA ballots between 1956 and 1973, garnering 40 percent of the vote in 1970, his best showing. And there is a reason why Marion is not already in the Hall of Fame, which we will now examine.Here are the five Hall of Fame shortstops associated with the Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) whose careers overlapped Marion's to some degree, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) Hall of Fame Shortstops and 2016 Shortstop Candidate on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Appling, Luke |

.310/.399/.398 |

.378 |

74.5 |

72.7 |

113 |

115 |

| Vaughan, Arky |

.318/.406/.453 |

.399 |

72.9 |

72.6 |

136 |

138 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

.269/.366/.377 |

.350 |

66.4 |

61.3 |

99 |

103 |

| Boudreau, Lou |

.295/.380/.415 |

.375 |

63.0 |

64.5 |

120 |

122 |

| Rizzuto, Phil |

.273/.351/.355 |

.335 |

40.8 |

41.3 |

93 |

96 |

| Marion, Marty |

.263/.323/.345 |

.317 |

31.6 |

30.0 |

81 |

83 |

The table below lists these five Hall of Fame shortstops associated with the Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) and Marion, ranked by JAWS, along with other JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all shortstops in the Hall of Fame.

| Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) 2016 Shortstop Candidate, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Shortstops (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Vaughan, Arky |

14 |

1932 |

1948 |

72.9 |

50.6 |

61.8 |

6 |

116 |

52 |

| Appling, Luke |

20 |

1930 |

1950 |

74.5 |

43.8 |

59.1 |

9 |

149 |

57 |

| Boudreau, Lou |

15 |

1938 |

1952 |

63.0 |

48.7 |

55.8 |

15 |

89 |

34 |

| Ave of 21 HoF SS |

NA |

NA |

NA |

66.7 |

42.8 |

54.7 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

16 |

1940 |

1958 |

66.4 |

41.0 |

53.6 |

17 |

100 |

39 |

| Rizzuto, Phil |

13 |

1941 |

1956 |

40.8 |

33.8 |

37.3 |

35 |

87 |

23 |

| Marion, Marty |

13 |

1940 |

1953 |

31.6 |

26.2 |

28.9 |

63 |

57 |

17 |

To be fair, the statistics featured in the two tables immediately above are weighted to a player's offensive ability, and shortstop is a position that has been considered to be primarily a defensive one since it had been created in the 19th century (and we'll examine Doc Adams in detail below). And although the Hall of Fame has historically rewarded position players for their offensive prowess much more so that for their defensive ability, it has recognized players whose reputation has rested primarily with their glove than with their bat, from Ray Schalk to Nellie Fox to Ozzie Smith.

So, let's examine whether Marion, who never hit more than six home runs in a single season (he retired with 36 dingers all told) nor came closer than 20 points of a .300 batting average in any given year, has the fielding wizardry to merit inclusion in the Hall of Fame—or at least justify his nicknames "The Octopus" and "Mr. Shortstop."

The table below lists the Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame shortstops from the live-ball period and Marion, ranked by dWAR, or Wins Above Replacement based on defensive effectiveness only, with other defensive metrics and their career stolen base totals.

| Defensive and Stolen-Base Statistics for Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) Hall of Fame Shortstops and 2016 Shortstop Candidate on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era (Live Ball) Era Ballot, Ranked by dWAR |

|||||||||

| Player |

Putouts |

Assists |

Double Plays Turned |

Total Zone |

dWAR |

Fld. Pct. |

RF/9 |

League RF/9 |

Stolen Bases |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

4040 |

5891 |

1246 |

107 |

25.6 |

.962 |

5.05 |

5.11 |

232 |

| Marion, Marty |

2986 |

4829 |

978 |

130 |

25.0 |

.969 |

5.27 |

5.24 |

35 |

| Boudreau, Lou |

3132 |

4760 |

1180 |

115 |

23.3 |

.954 |

5.27 |

5.13 |

51 |

| Rizzuto, Phil |

3219 |

4666 |

1217 |

107 |

22.9 |

.968 |

5.20 |

5.09 |

149 |

| Appling, Luke |

4398 |

7218 |

1424 |

39 |

19.0 |

.948 |

5.35 |

5.21 |

179 |

| Vaughan, Arky |

2995 |

4780 |

850 |

17 |

12.0 |

.951 |

5.36 |

5.43 |

118 |

Among his contemporaries already in the Hall of Fame, Marty Marion emerges as the elite fielder, tops in Total Zone defensive runs saved and just a tick over a half-win behind Pee Wee Reese in defensive WAR while he just beats out Phil Rizzuto for the highest fielding percentage, although his range factor compared to the league's suggest that "The Octopus"'s tentacles might not have been as long as previously perceived. Nevertheless, Marion has at least the defensive qualifications to justify his consideration for the Hall.

However, does Marion hold up against all shortstops considered to be outstanding defensive players? Ranked by Baseball Reference's defensive WAR, Marion is tied for 17th all-time among fielders at all positions—and as an indication of the defensive value of a shortstop, all but six of those first 17 slots are filled by shortstops. (Marion shares 17th place with fellow shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh and catcher Jim Sundberg.)

The table below lists defensive statistics (and career stolen bases) for the 17 shortstops on the list of all position players with the 25 highest defensive WAR values all-time. Ten of those shortstops are in the Hall of Fame (denoted by a +) while both Bill Dahlen and Marty Marion are on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era ballot (both indicated in bold italic). (Omar Vizquel will be eligible for the Hall of Fame in 2018.)

| Defensive and Stolen-Base Statistics for the Top 16 Hall of Fame Shortstops and 2016 Shortstop Candidates on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by dWAR |

|||||||||

| Player |

Putouts |

Assists |

Double Plays Turned |

Total Zone |

dWAR |

Fld. Pct. |

RF/9 |

League RF/9 |

Stolen Bases |

| Smith, Ozzie + |

4249 |

8375 |

1590 |

239 |

43.4 |

.978 |

5.22 |

4.78 |

580 |

| Belanger, Mark |

3005 |

5786 |

1054 |

238 |

39.4 |

.977 |

5.16 |

4.93 |

167 |

| Ripken, Jr., Cal + |

3651 |

6977 |

1565 |

176 |

34.6 |

.979 |

4.73 |

4.69 |

36 |

| Tinker, Joe + |

3768 |

5856 |

671 |

180 |

34.3 |

.938 |

5.63 |

5.40 |

336 |

| Aparicio, Luis + |

4548 |

8016 |

1553 |

149 |

31.6 |

.972 |

5.05 |

4.89 |

506 |

| Maranville, Rabbit + |

5139 |

7354 |

1188 |

115 |

30.8 |

.952 |

5.92 |

5.64 |

291 |

| Wallace, Bobby + |

4142 |

6303 |

640 |

105 |

28.7 |

.938 |

5.89 |

5.61 |

201 |

| Dahlen, Bill |

4856 |

7505 |

881 |

120 |

28.4 |

.927 |

5.96 |

5.67 |

548 |

| Vizquel, Omar |

4102 |

7676 |

1734 |

137 |

28.4 |

.985 |

4.62 |

4.35 |

404 |

| Fletcher, Art |

2836 |

5134 |

620 |

145 |

28.3 |

.939 |

5.67 |

5.50 |

160 |

| Reese, Pee Wee + |

4040 |

5891 |

1246 |

107 |

25.6 |

.962 |

5.05 |

5.11 |

232 |

| Marion, Marty |

2986 |

4829 |

978 |

130 |

25.0 |

.969 |

5.27 |

5.24 |

35 |

| Peckinpaugh, Roger |

3919 |

6337 |

966 |

100 |

25.0 |

.949 |

5.31 |

5.25 |

205 |

| Davis, George + |

3239 |

4794 |

590 |

106 |

24.0 |

.940 |

6.04 |

5.74 |

619 |

| Bancroft, Dave + |

4623 |

6561 |

1021 |

94 |

23.4 |

.944 |

6.12 |

5.70 |

145 |

| Boudreau, Lou + |

3132 |

4760 |

1180 |

115 |

23.3 |

.954 |

5.27 |

5.13 |

51 |

| McBride, George |

3585 |

5274 |

609 |

98 |

23.2 |

.948 |

5.56 |

5.41 |

133 |

Leaving aside the wide variances in the style and quality of play these fielders faced depending on when they played, Marty Marion emerges as a viable if not auspicious candidate at least in terms of defensive play. But even if the shortstop position rewards defensive play as a Hall of Fame qualification, it is not the exclusive, or even the dominant, criterion—were that the case, Mark Belanger, with a career slash line of .228/.300/.280 and 20 home runs in more than 2000 games, would have been inducted by now.

To assess the offensive contribution these defensive stars made during their career, let's examine Hall of Fame shortstops and current Pre-Integration Era shortstop candidate Bill Dahlen included in the table immediately above, whose "slash line" (batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage) are comparable to Marty Marion's, first qualitatively and then quantitatively.

The table below lists those shortstops just identified with their respective qualitative statistics, ranked by bWAR.

| Hall of Fame Shortstops (All Eras) and 2016 Shortstop Candidates on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Smith, Ozzie |

.262/.337/.328 |

.305 |

76.5 |

67.6 |

87 |

90 |

| Dahlen, Bill |

.272/.358/.382 |

.357 |

75.2 |

77.5 |

110 |

108 |

| Wallace, Bobby |

.268/.332/.358 |

.333 |

70.2 |

62.4 |

105 |

104 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

.269/.366/.377 |

.350 |

66.4 |

61.3 |

99 |

103 |

| Aparicio, Luis |

.262/.311/.343 |

.296 |

55.7 |

49.1 |

82 |

83 |

| Tinker, Joe |

.262/.308/.353 |

.319 |

53.2 |

55.5 |

96 |

96 |

| Bancroft, Dave |

.279/.355/.358 |

.342 |

48.5 |

49.2 |

98 |

100 |

| Maranville, Rabbit |

.258/.318/.340 |

.313 |

42.8 |

42.5 |

82 |

83 |

| Rizzuto, Phil |

.273/.351/.355 |

.335 |

40.8 |

41.3 |

93 |

96 |

| Marion, Marty |

.263/.323/.345 |

.317 |

31.6 |

30.0 |

81 |

83 |

The table below lists those shortstops with selected quantitative statistics (i.e., "counting numbers"). These statistics reflect those of a "table-setting" hitter, typically in the lead-off or number-two spot in the batting order, whose duties include getting on base, stealing bases, and moving up runners. Listed in the table are hits, doubles, triples, runs scored, bases on balls, stolen bases, and sacrifice hits.

| Hall of Fame Shortstops (All Eras) and 2016 Shortstop Candidates on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by Hits |

|||||||

| Position Player |

H |

2B |

3B |

R |

BB |

SB |

SH |

| Aparicio, Luis |

2677 |

394 |

92 |

1335 |

736 |

506 |

161 |

| Maranville, Rabbit |

2605 |

380 |

177 |

1256 |

839 |

291 |

300 |

| Dahlen, Bill |

2461 |

413 |

163 |

1590 |

1064 |

548 |

*165 |

| Smith, Ozzie |

2460 |

402 |

69 |

1257 |

1072 |

580 |

214 |

| Wallace, Bobby |

2309 |

391 |

143 |

1057 |

774 |

201 |

173 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

2170 |

330 |

80 |

1338 |

1210 |

232 |

157 |

| Bancroft, Dave |

2004 |

320 |

77 |

1048 |

827 |

145 |

212 |

| Tinker, Joe |

1690 |

263 |

114 |

774 |

416 |

336 |

285 |

| Rizzuto, Phil |

1588 |

239 |

62 |

877 |

651 |

149 |

193 |

| Marion, Marty |

1448 |

272 |

37 |

602 |

470 |

35 |

151 |

It should be noted that Marion played the fewest games of the ten shortstops profiled, and thus it partially explains why some of his counting numbers, including hits, are the lowest of the sample, which is why he is at the bottom of the list. On the other hand, Marion was also ranked last in the previous table of qualitative statistics, and by now a clear picture of Marion should be emerging.

Marion most closely resembles Phil Rizzuto, whose career overlapped almost identically with Marion's as both shortstops played for a total of 13 seasons each. However, Rizzuto lost three years of his career during World War Two when he served in the US Navy from 1943 to 1945, his age-25 through age-27 seasons. By contrast, Marion, who was only three months younger than Rizzuto, played throughout the war, and in fact had his best seasons during the war, when the talent pool was diluted (as we noted while examining Frank McCormick).

In 1944, Marion was even named the National League's Most Valuable Player, a selection that, much like McCormick's MVP award in 1940, has been criticized over the decades. Marion was certainly an integral part of the St. Louis Cardinals team that won the NL pennant that year and then beat the crosstown St. Louis Browns in the World Series in six games, but Marion's teammate Stan Musial had another stellar year in 1944, finishing at or near the top of most major offensive categories, and would seem to have been a more deserving recipient, as would have Bill Nicholson of the Chicago Cubs, who led the NL in home runs and RBI, or Dixie Walker of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who led the league in batting. Even if the award were for Marion's defensive performance, he was bested at shortstop by the Cincinnati Reds' Eddie Miller in every category except fielding percentage, which Marion took by one percentage point over Miller.

Musial came in fourth in voting after having won his first MVP award in 1943; he won another MVP award in 1946 after having missed the 1945 season because of his military service in the US Navy.

Returning to Marty Marion and Phil Rizzuto: After Rizzuto's playing career ended, he became an announcer for the New York Yankees, the team for whom he played his entire career. Rizzuto became the Yankees' longest-serving announcer, having broadcast games for 40 years, and that was likely a factor in helping him be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the veterans committee in 1994.

Marion became a manager for six seasons, first for his Cardinals in 1951, the year after he retired as a player. Then in 1952 he moved across town to become the player-manager for the Browns for two seasons although his playing time in 1953, at third base, was negligible. After the Browns left town for Baltimore (they became the Orioles), Marion moved to the Chicago White Sox where he was a coach for much of the 1954 season before becoming manager for the final few games; he returned as manager for the next two years. Marion's managerial record is hardly auspicious in aggregate—he won 356 games and lost 372 for a .489 winning percentage—although his management of the hapless Browns, one of the most woeful franchises in Major League history, skews his record as a manager. In two seasons, his Browns won 96 and lost 161, but he notched an 81–73 record for the Cardinals while totaling 179 wins against 138 losses for the White Sox, including a high of 91 wins in 1955; however, his non-Browns teams finished in third place in each of those five seasons.

Rizzuto's admission into the Hall of Fame has been criticized because of his lightweight credentials. Rizzuto did win an MVP award in the American League in 1950, when he established career highs in more than a dozen offensive categories including hits (200), doubles (36), home runs (7), runs scored (125), walks (92), and overall slash line (.324/.418/.439); Rizzuto also led the AL in sacrifice hits with 19 and thus became the only position-player MVP to lead his league in that category. Moreover, his bWAR of 6.7 was best among just about every candidate who received an MVP vote; the Cleveland Indians' Larry Doby, who finished eighth in voting, posted a 6.7 bWAR as well.

As for the other shortstops with similar qualitative offensive statistics in this sample, almost all of them have at least one notable quantitative statistic in his resume—Aparicio, Dahlen, and Smith all swiped at least 500 bases, for example, while even Maranville, a rare example of a dubious BBWAA election, still collected more than 2600 hits. Marion, on the other hand, is uniformly inauspicious.

Based on the statistical record, Marty Marion is one of the best defensive shortstops in Major League history, but even with three World Series rings and one suspect MVP award under his belt, Marion is not a Hall of Famer.

Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame Left Fielder: 19th Century

As we have seen, Bill Dahlen has been legitimately overlooked for the Hall of Fame, perhaps because his career straddled the 19th and 20th centuries, leaving his legacy behind in the mists of baseball history. That could make it even more difficult for Harry Stovey, whose career spanned the years from 1880 to 1893, encompassing the pre-modern game with its significant differences from the baseball we know today coupled with a fragmented statistical record and nothing but bygone accounts of his feats with which to evaluate him.On the other hand, the Nineteenth Century Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research declared that Stovey was its Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend for 2011, and although Stovey did not appear on the Pre-Integration Committee's 2013 ballot, he has made the current ballot, which gives us the opportunity to examine his Hall of Fame worthiness.

Here are the five Hall of Fame left fielders associated with the 19th-century Pre-Integration Era whose careers mostly overlapped Stovey's to some degree, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it. Fred Clarke's career began one year after Stovey had retired, but it is included to increase the sample size.

| 19th-Century Pre-Integration Era Hall of Fame Left Fielders and 2016 Left Fielder Candidate on the 2016 Pre-Integration Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Delahanty, Ed |

.346/.411/.505 |

.428 |

69.5 |

73.7 |

152 |

144 |

| Clarke, Fred |

.312/.386/.429 |

.390 |

67.8 |

72.8 |

133 |

131 |

| Burkett, Jesse |

.338/.415/.446 |

.411 |

62.9 |

66.6 |

140 |

137 |

| O'Rourke, Jim |

.310/.352/.422 |

.360 |

51.3 |

52.1 |

134 |

127 |

| Kelley, Joe |

.317/.402/.451 |

.405 |

50.6 |

54.9 |

134 |

130 |

| Stovey, Harry |

.289/.361/.461 |

.380 |

45.1 |

54.9 |

144 |

132 |

Those five Hall of Fame left fielders are listed in the table below, ranked by JAWS, with other JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all left fielders in the Hall of Fame.

| 2016 19th-Century Pre-Integration Era Left Field Candidate, Qualitative Comparisons to 19th-Century Hall of Fame Left Fielders (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Delahanty, Ed |

16 |

1888 |

1903 |

69.5 |

48.5 |

59.0 |

6 |

234 |

65 |

| Ave of 19 HoF LF |

NA |

NA |

NA |

65.1 |

41.5 |

53.3 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Clarke, Fred |

21 |

1894 |

1915 |

67.8 |

36.1 |

52.0 |

12 |

86 |

50 |

| Burkett, Jesse |

16 |

1890 |

1905 |

62.9 |

37.2 |

50.0 |

13 |

191 |

56 |

| Kelley, Joe |

17 |

1891 |

1908 |

50.6 |

36.2 |

43.4 |

23 |

98 |

52 |

| Stovey, Harry |

14 |

1880 |

1893 |

45.1 |

31.1 |

38.1 |

37 |

86 |

34 |

| O'Rourke, Jim |

23 |

1872 |

1904 |

51.3 |

24.2 |

37.8 |

39 |

84 |

49 |

Stovey may be overlooked but compared to the 19th-century left fielders already in the Hall of Fame, he lands at the bottom of the rankings. He did have the shortest career of them all, and WAR and JAWS statistics tend to favor players with longer careers and thus more opportunities to provide value.

In this respect, Stovey compares most closely to Jim O'Rourke, whose career was more than one-third longer than Stovey's, reflected in O'Rourke's bWAR—although FanGraphs' WAR rating is bullish on Stovey and nudges him ahead of O'Rourke, while JAWS, which averages peak seasons and overall value, has Stovey just ahead of O'Rourke. (O'Rourke's playing career effectively ended in 1893, although he pulled a Minnie Miñoso and appeared in one game for the New York Giants in 1904, getting a single in four at-bats, and at age 53 becoming the oldest player to hit safely in Major League history.) O'Rourke's Hall of Fame induction by the veterans committee came fairly early, in 1945, largely because for Major League Baseball's first decade and a half, he ranked behind only Cap Anson in several categories—and behind only Stovey in runs scored.

Stovey ranks 73rd in career runs scored with 1492, nestled between Hall of Famers Frank Thomas (1494) and Goose Goslin (1482) on the all-time list (O'Rourke ranks 24th with 1729), 21st in triples with 174 and 34th in stolen bases with 509, keeping in mind that stolen bases were not even recorded as an official statistic until 1886 and that the rules regarding base-stealing as we know it today were not fully implemented until 1898, five years after Stovey's career ended.

With his fourth home run for the National League's Boston Beaneaters in 1891, Stovey became the first Major League hitter to hit 100 home runs; he finished his career with 122. Stovey led the league in round-trippers five times, including a career-high 19 in 1889, while notching double-digit totals in six different seasons. In addition, he led the league in triples four times and posted double-digit season totals eleven times, hitting 20 or more three-baggers three times with a career-best 23 in 1884. His slugging prowess is also reflected in his leading the league in total bases and in slugging percentage three times each. And although his stolen-base record is fragmentary and subject to the rules of the time, Stovey was a league-leader twice, swiping a career-high 97 bags in 1890 while collecting 40 or more in seven consecutive years from 1886 to 1892. Stovey also led the league in runs scored four times, three of those in consecutive seasons as he had nine consecutive seasons with 100 or more runs scored, and he led the league in RBI once.

Flashing both power and speed, Harry Stovey was the prototype of the modern 30-30 hitter even if the first 30-home-run season did not occur until a quarter-century after his retirement. (Babe Ruth's 54 homers in 1920 marked the first crossing of the 30-homer threshold, although Ruth had fallen one shy of that in the previous season, and Ned Williamson had hit 27 homers back in 1884.) Stovey was among the league leaders in both power-hitting (triples and home runs) and baserunning, and for a six-year stretch from 1886 to 1891 he averaged 14 triples, 11 home runs, and 74 stolen bases along with a .292/.380/.471 slash line, 130 runs scored, 83 RBI, and a 146 OPS+.

Like Bill Dahlen, Harry Stovey is considered to be an overlooked 19th-century baseball player worthy of the Hall of Fame. And even though Dahlen is not strictly, or even primarily, a 19th-century player, let's compare both Dahlen and Stovey to those Hall of Famers whose careers did occur exclusively or primarily during the late 1800s.

The following table ranks those players along with Dahlen and Stovey by bWAR while including their other significant qualitative statistics.

| 19th-Century Pre-Integration Era 2016 Candidates and All Hall of Fame Players Active During Candidates' 19th-Century Career, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Player and Position |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Anson, Cap, 1B |

.334/.394/.447 |

.393 |

93.9 |

91.2 |

142 |

134 |

| Davis, George, SS |

.295/.362/.405 |

.366 |

84.7 |

84.6 |

121 |

118 |

| Connor, Roger, 1B |

.316/.397/.486 |

.409 |

84.1 |

86.2 |

153 |

143 |

| Brouthers, Dan, 1B |

.342/.423/.519 |

.436 |

79.4 |

79.5 |

170 |

156 |

| Dahlen, Bill, SS |

.272/.358/.382 |

.357 |

75.2 |

77.5 |

110 |

108 |

| Delahanty, Ed, LF |

.346/.411/.505 |

.428 |

69.5 |

73.7 |

152 |

144 |

| Clarke, Fred, LF |

.312/.386/.429 |

.390 |

67.8 |

72.8 |

133 |

131 |

| Beckley, Jake, 1B |

.308/.361/.436 |

.376 |

64.5 |

61.2 |

125 |

119 |

| Hamilton, Billy, CF |

.344/.455/.432 |

.433 |

63.3 |

70.3 |

141 |

142 |

| Burkett, Jesse, LF |

.338/.415/.446 |

.411 |

62.9 |

66.6 |

140 |

137 |

| Keeler, Willie, RF |

.341/.388/.415 |

.383 |

54.0 |

55.7 |

127 |

124 |

| McPhee, Bid, 2B |

.272/.355/.373 |

.350 |

52.4 |

62.7 |

107 |

108 |

| O'Rourke, Jim |

.310/.352/.422 |

.360 |

51.3 |

52.1 |

134 |

127 |

| Kelley, Joe, LF |

.317/.402/.451 |

.405 |

50.6 |

54.9 |

134 |

130 |

| Ewing, Buck, C |

.303/.351/.456 |

.372 |

47.7 |

48.1 |

129 |

123 |

| White, Deacon, 3B |

.312/.346/.393 |

.343 |

45.5 |

41.1 |

127 |

121 |

| Stovey, Harry, LF |

.289/.361/.461 |

.380 |

45.1 |

54.9 |

144 |

132 |

| Kelly, King, RF |

.308/.368/.438 |

.375 |

44.3 |

45.1 |

139 |

131 |

| Thompson, Sam, RF |

.331/.384/.505 |

.409 |

44.3 |

44.1 |

147 |

136 |

| Duffy, Hugh, CF |

.326/.386/.451 |

.394 |

43.0 |

48.3 |

123 |

118 |

| Jennings, Hughie, SS |

.312/.391/.406 |

.385 |

42.3 |

44.9 |

118 |

119 |

| Ward, John, SS |

.275/.314/.341 |

.311 |

35.6 |

39.8 |

92 |

97 |

| Hanlon, Ned, CF |

.260/.325/.340 |

.317 |

18.0 |

19.2 |

102 |

104 |

| McCarthy, Tommy, RF |

.292/.364/.375 |

.358 |

16.1 |

23.3 |

102 |

105 |

| Robinson, Wilbert, C |

.273/.316/.346 |

.317 |

13.9 |

12.8 |

83 |

84 |

Because all of these players inducted into the Hall of Fame were elected by veterans committees, that election does not rely exclusively on players' performance records on the field. Both Ned Hanlon and Wilbert Robinson are more celebrated as managers, with Hanlon especially considered to be a landmark strategist credited with having invented the hit-and-run play; he is known as "the Father of Modern Baseball."

Meanwhile, John Ward, also known as John Montgomery Ward, was both a player—the only player in history to win at least 100 games as a pitcher and to collect at least 2000 hits as a batter—and a manager although he is also notable in baseball history for forming his own league, the Players' League, which lasted for only one season, 1890, although it had attracted many star players, including Harry Stovey, while offering a players' profit-sharing plan and no reserve clause, progressive business practices most atypical of the Gilded Age and subsequently ignored in baseball for several decades. Furthermore, Ward was an attorney (as was O'Rourke), most unusual at the time and even now, who after his playing days represented players and held front-office jobs.

On the other hand, Tommy McCarthy can consider himself to be the luckiest Hall of Fame player ever as no less than sabermetrics godfather Bill James considers him to be the worst player enshrined in the Hall.

The following table contains the JAWS statistics for these 19th-century players along with Hall of Fame Monitor and Hall of Fame Standards ratings. It is important to note that several players, notably John Ward, played at various positions throughout their careers, and although the statistics represent their aggregate record, Jay Jaffe's JAWS system places them at the position at which they had the most value. In addition, the JAWS Rank is for each player at the position at which he is identified and is not an overall ranking of all positions combined.

| 2016 19th-Century Pre-Integration Era Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to 19th-Century Hall of Famers, All Positions (Ranked by JAWS) |

|||||||||

| Player and Position |

No. of Yrs. |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Anson, Cap, 1B |

27 |

1871 |

1897 |

93.9 |

41.7 |

67.8 |

4 |

186 |

64 |

| Davis, George, SS |

20 |

1890 |

1909 |

84.7 |

44.3 |

64.5 |

4 |

81 |

54 |

| Connor, Roger, 1B |

18 |

1880 |

1897 |

84.1 |

47.0 |

65.5 |

5 |

104 |

56 |

| Brouthers, Dan, 1B |

19 |

1879 |

1904 |

79.4 |

47.2 |

63.3 |

7 |

162 |

54 |

| Delahanty, Ed, LF |

16 |

1888 |

1903 |

69.5 |

48.5 |

59.0 |

6 |

234 |

65 |

| Dahlen, Bill, SS |

21 |

1891 |

1911 |

75.2 |

40.1 |

57.7 |

10 |

94 |

48 |

| Hamilton, Billy, CF |

14 |

1888 |

1901 |

63.3 |

42.6 |

53.0 |

13 |

154 |

51 |

| Clarke, Fred, LF |

21 |

1894 |

1915 |

67.8 |

36.1 |

52.0 |

12 |

86 |

50 |

| Burkett, Jesse, LF |

16 |

1890 |

1905 |

62.9 |

37.2 |

50.0 |

13 |

191 |

56 |

| Beckley, Jake, 1B |

20 |

1888 |

1907 |

61.5 |

29.8 |

45.7 |

26 |

84 |

50 |

| Keeler, Willie, RF |

19 |

1892 |

1910 |

54.0 |

36.2 |

45.1 |

26 |

189 |

49 |

| Kelley, Joe, LF |

17 |

1891 |

1908 |

50.6 |

36.2 |

43.4 |

23 |

98 |

52 |

| McPhee, Bid, 2B |

18 |

1882 |

1899 |

52.4 |

29.3 |

40.8 |

27 |

74 |

43 |

| Jennings, Hughie |

18 |

1891 |

1918 |

42.3 |

39.0 |

40.6 |

28 |

88 |

34 |

| Ewing, Buck, C |

18 |

1880 |

1897 |

47.7 |

30.5 |

39.1 |

15 |

35 |

38 |

| Thompson, Sam, RF |

15 |

1885 |

1906 |

44.3 |

33.2 |

38.7 |

36 |

174 |

47 |

| Stovey, Harry, LF |

14 |

1880 |

1893 |

45.1 |

31.1 |

38.1 |

37 |

86 |

34 |

| O'Rourke, Jim, LF |

23 |

1872 |

1904 |

51.3 |

24.2 |

37.8 |

39 |

84 |

49 |

| Kelly, King, RF |

16 |

1878 |

1893 |

44.3 |

31.1 |

37.7 |

42 |

64 |

45 |

| Duffy, Hugh, CF |

17 |

1888 |

1906 |

43.0 |

30.8 |

36.9 |

46 |

155 |

55 |

| White, Deacon, 3B |

20 |

1871 |

1890 |

45.5 |

26.0 |

35.7 |

36 |

47 |

35 |

| Ward, John, SS |

17 |

1878 |

1894 |

35.6 |

24.7 |

30.1 |

57 |

42* |

28* |

| McCarthy, Tommy, RF |

13 |

1884 |

1896 |

16.1 |

18.9 |

17.5 |

130 |

44 |

24 |

| Hanlon, Ned, CF |

13 |

1880 |

1892 |

18.0 |

14.2 |

16.1 |

163 |

12 |

12 |

| Robinson, Wilbert, C |

17 |

1886 |

1902 |

13.9 |

11.8 |

12.8 |

135 |

25 |

24 |

Compared to all of the 19th-century Hall of Fame players, it is easy to see why Harry Stovey was overlooked: Stovey is an excellent player but clearly on the bubble. Given the contemporary preference for hitters with power and speed, Stovey does appear attractive in that light, and as noted previously, he did post some impressive numbers to illustrate those qualities.

In terms of value, it is interesting to note that Stovey closely resembles Deacon White, who was the Pre-Integration Committee's sole player choice the last time it convened. White is almost a half-game higher in win value than Stovey, with Stovey making a slightly bigger impact with his peak seasons and with his JAWS rating although that may be marginal because even though White had a longer career, one that predates the formation of the National League in 1876 and thus marking the start of Major League Baseball as we know it today, Stovey is not far behind White in games played and plate appearances.