This is in response to last year's Dan le Batard incident, in which the Miami Herald sportswriter, to protest what he felt was the "moralizing" pervasive in recent voting to punish players on the ballot with performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) associations, "sold" his ballot to the sports website Deadspin and let the site complete the ballot. (Le Batard had Deadspin donate the money to a charity.) For his actions, le Batard was suspended from the BBWAA for one year, and he has been banned permanently from voting on Hall of Fame ballots starting with this one.

And starting with this year's vote, the names of all members who cast a ballot will be made public at the time the results are announced; however, how they voted will not be revealed unless the member does so of his or her own volition (as many voting members have been doing for some time).

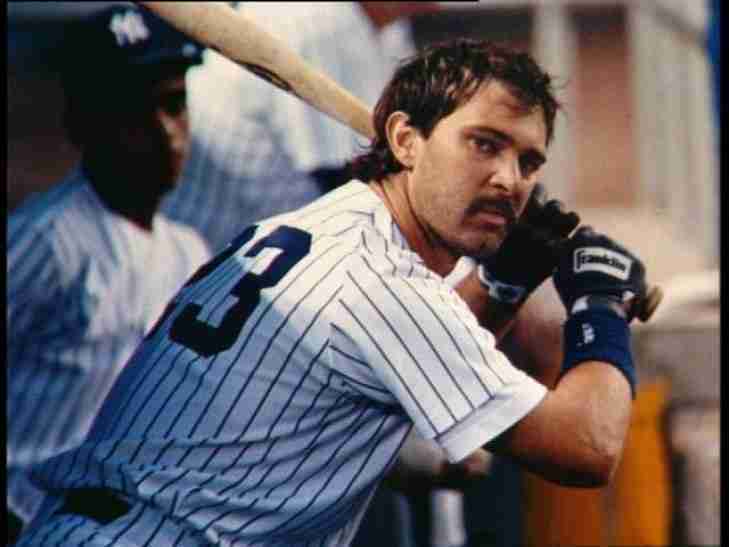

But the big change is the reduction in the number of years of eligibility a candidate for the Hall of Fame may have to remain on the ballot. (Previous restrictions still apply: A candidate must collect at least five percent of the vote to remain on the ballot, and of course any candidate who collects at least 75 percent of the vote is thus elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.) The three candidates on the current ballot who have been on previous ballots for more than ten years already—Don Mattingly, Lee Smith, and Alan Trammell—will be grandfathered until they are elected, receive less than five percent of the vote, or reach their fifteenth year without election; Mattingly is in his fifteenth year currently.

Why the change to the number of years of eligibility? The answer is simple for anyone remotely aware of one of the two issues afflicting the ballot in recent years, and that is the logjam of qualified candidates for the Hall of Fame. The other issue is the question of players associated with PEDs. Both the Hall of Fame and the BBWAA have been grappling with these two issues for the past few years and will continue to do so. Let's look at these issues more closely.

Punting and Pontificating: Hall of Fame Ballot Issues

The good news is that we truly live in blessed times with respect to Hall of Fame-caliber players—there are so many of them. (In 2013, I identified 14 likely Hall of Famers on that ballot, and on last year's ballot I identified 18 likely Hall of Famers.) We live in an era of high talent compression, meaning that there are so many excellent players in the major leagues and have been for the last three decades—just check out any retrospective highlight-reel show.The downside is that with so many quality players, so many of those have a harder time standing out from an impressive pack, making it in turn harder to recognize them as potential Hall of Famers. Nevertheless, they are on the ballot, and that is crux of the problem—even with a maximum of ten candidates a voter can choose on his or her ballot, there are still going to be candidates who deserve the recognition but will not get it in that voting year. Compounding that is the problem of mustering the minimum of 75 percent of the vote for each noteworthy candidate, who remains on subsequent ballots (provided each candidate receives at least five percent of the vote), and the cumulative result is a steadily growing number of qualified candidates as each year adds more candidates whose qualifications are also Hall-worthy.

And it is not as if the BBWAA is voting gratuitously, or has done so. The single largest class voted into the Hall by the writers was the inaugural Class of 1936, when five players were elected. It may go without saying that those early ballots were similarly overstuffed with qualified candidates, many of whom were eventually elected, but historically the BBWAA has been parsimonious: It has voted in four candidates in a single year only three times—even a blue moon occurs every two or three years—and the last time that happened was in 1955. (The previous two times were once each in the preceding two decades, in 1939 and in 1947, and in 1939 that fourth candidate, Lou Gehrig, was a special vote by acclamation stemming from Gehrig's forced retirement due to the ultimately fatal neurodegenerative disorder now named for him.) The writers have voted in three candidates on a single ballot seven times, most recently last year, but that too seems like an unlikely occurrence, with a frequency of about once per decade (about as often as the national census): Prior to 2014, the last three-player election was in 1999, with others occurring (in reverse order) in 1991, 1984, 1972, 1954, and 1937.

Six times the BBWAA was unable to elect a candidate, the most recent being 2013, when with a ridiculously overstuffed ballot the writers were unable to muster 75 percent for any one candidate; the other five years in which the BBWAA was unable to elect a candidate were 1950, 1958, 1960, 1971, and 1996. And since 1936, there have been 11 years in which no vote was held at all. The first two times were in 1940 and 1941, and after a vote in 1942 elected one player (Rogers Hornsby, and arguably the greatest right-handed hitter in baseball history squeaked into the Hall with 78.11 percent of the vote), the BBWAA held no voting from 1943 to 1946, resuming its voting in 1947 and making up for lost time by electing four players (Mickey Cochrane, Frankie Frisch, Lefty Grove, and Carl Hubbell). Then, from 1956 to 1966, the BBWAA voted only in alternate, odd-numbered years, with the veterans committee voting in even-numbered years, and from 1967 on the writers resumed annual voting.

In the 68 years from 1936 to 2014 during which the BBWAA held an annual vote, with six years in which a vote was held but no candidate elected, the writers have elected 102 players. That works out to exactly 1.5 candidates per year—and this year's ballot, as with the previous two years' ballots, certainly has more than one-and-a-half qualified candidates even if you remove any candidate with even a hint of association with performance-enhancing drugs.

The reason advanced by the Baseball Hall of Fame for shortening the time allotted for a candidate on a Hall ballot is that the large majority of players who have been elected have been elected within the first ten years of eligibility. (The BBWAA had no say in the decision; the BBWAA has been selected by the Baseball Hall of Fame to be its adjudicating body, but rules governing the conditions by which candidates are elected are the province of the Hall.)

Whether the Hall's rationale is valid or justified, whether it is a necessary measure to alleviate the ballot logjam, its consequences are crystal-clear: The Baseball Hall of Fame is punting responsibility for full consideration of a candidate's worthiness for the Hall of Fame to the Expansion Era Committee, the veterans committee for the period starting from 1973 that votes every three years and that currently comprises a mix of Hall of Fame members (both players and non-players), executives, and media members, although as it stands now the large majority of the individuals from each area change from session to session.

The rule change from 15 years to 10 years will have a short-term benefit, if the "benefit" is simply to remove candidates from the ballot. They may in fact be Hall of Fame-caliber candidates, and factors other than their perception of not being immediate and obvious Hall-worthy candidates may be significant ones, such as a voting member being limited to voting for no more than ten candidates on any one ballot, and the requirement that a candidate must receive at least 75 percent of the vote to be elected. But determination of whether a candidate who is not an immediate and obvious choice as a genuine Hall of Famer—or because of the ballot logjam simply cannot garner that required 75 percent—has now been removed from the writers after ten years and handed to the Expansion Era Committee sooner than had been the procedure previously.

The Expansion Era Committee, one of three separate veterans committees that include the Pre-Integration Era (1876–1946) and the Golden Era (1947–1972) Committees and that meet annually on a rotating basis, has met twice since the committees' 2010 inception. The Committee elected executive Pat Gillick in 2011 and in 2014 elected three managers—Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa, and Joe Torre, although Torre was a near-Hall of Famer as a player. And in 2012 the Golden Era Committee did right a long-standing wrong and elected third baseman Ron Santo to the Hall. However, that Golden Era Committee met again this year for the 2015 class and did not elect one candidate from a field of ten, which included nine players.

That inability to elect a candidate, echoing the inability of the BBWAA to elect a candidate in 2013, has generated criticism of this year's Golden Era Committee in particular and the veterans committee process in general, and it suggests that the shortening of the term of eligibility on the BBWAA ballot from fifteen years to ten years is simply a stop-gap solution designed to clear the logjam but does nothing to rectify the issue of properly evaluating candidates and providing a fair mechanism to elect the deserving ones. (And with respect to this year's Golden Era Committee and its failure to elect even one candidate, I did recently a lengthy analysis of that Golden Era's ten candidates, nine players and one executive, and I concluded that although two or even three of the player-candidates came close to the Hall of Fame threshold, none were bona fide Hall of Famers who had been unfairly overlooked either by the writers or by previous veterans committees.)

Swept up—and swept under the rug—by the change in the term of eligibility are players with known or admitted associations with performance-enhancing drugs, and players merely suspected of having used PEDs even if there is no evidence of their having done so. They too are being shunted off the ballot and into the basket of issues that future Expansion Era Committees are now being asked to solve (or not), and although I do not think that the shortening of the term of eligibility was done specifically with the PEDs players in mind—Problem One is a much bigger one, and that is the logjam of qualified candidates regardless of "cleanliness"—it is a convenient by-product of the decision.

And, again, there should be no doubt by now that this year's ballot, as with ballots from the past several years and as with ballots for the next several years, are referendums on the Steroids Era—and it is crystal-clear what the majority opinion on the matter is: If a player has a PEDs association, whether actual or alleged, he is not going to receive a 75-percent majority of the votes needed for election. And as the other rule change instituted by the Hall of Fame this year makes clear, any attempt to protest this majority opinion, such as what Dan le Batard did by giving his ballot to a non-eligible entity, will be met by swift punishment: a one-year suspension from the BBWAA and a permanent ban from Hall of Fame voting. Of course, a voting member could protest within the restrictions—vote only for players with known or alleged PEDs associations—but that does little to solve the issue.

(What would be most intriguing, if highly unlikely, is if a protest as just described somehow managed to elect one or more of those tainted players to the Hall: Would the Hall, or Major League Baseball, find a reason to question the vote? Would this result in a voting audit? Would some restriction be instituted to somehow thwart the results? Or, if a player is invited to Cooperstown for the ceremony, would the ceremony take place—but all, or at least some, of the usual dignitaries send videotapes of congratulation, as what happened when Barry Bonds broke Hank Aaron's career home-run record?)

We will not re-visit the PEDs issue here—I explored the issue at length during analysis of the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot—except to say that it has two near-absolute certainties: one is that the issue is not going away, even if some of the players implicated in the issue may be going away sooner thanks to the shortened time allotted on a ballot, and, two, the consensus is that any player simply suspected of PEDs involvement is highly unlikely to be elected to the Hall of Fame.

In sum, as the pontificating by BBWAA voting members over players with PEDs associations continues apace, the Hall of Fame has decided to punt overall deliberation of candidates away from the BBWAA and to the Expansion Era Committee (or whatever its equivalent may be in upcoming years) sooner rather than later by reducing the maximum time allotted on a ballot to ten years.

These two factors have an overriding effect on the evaluation of the qualification of a candidate for the Baseball Hall of Fame. How will voters react? Will there be a change in their approach? For my hypothetical ballot that I will reveal later in this article, these two factors have changed my perception of how I would vote if I had a vote in the 2015 Baseball Hall of Fame election. But before we get to that, let's look at the 34 candidates on that ballot.

Candidates for the 2015 Hall of Fame Ballot

For the 2015 ballot, there are 34 total candidates, 17 returning candidates from previous ballots and 17 first-time-eligible candidates. The returning candidates have garnered at least five percent of the vote last year (the minimum percentage required to remain eligible) and they have not exceeded their 15th year on the ballot. Last year, Jack Morris did not receive 75 percent of the vote in his final year of eligibility and was dropped from the ballot without being elected to the Hall of Fame. (Morris's next chance for the Hall is on a future Expansion Era Committee ballot.)This year, Don Mattingly is in his final year of eligibility, Alan Trammell is in his 14th year this year, while Lee Smith is in his 13th year. With the rule change effective this year that limits a candidate to ten years total on a BBWAA ballot, provided the candidate maintains at least five percent of the vote during each year, all three of these candidates have been grandfathered onto this ballot; should Trammell and Smith survive this round, they will make it onto the 2016 ballot, which, barring election this year, will be Trammell's last chance; Smith , barring election (or receipt of less than five percent of the vote) this year or in 2016, will face his final ballot in 2017.

The remaining returning candidates are Jeff Bagwell, Craig Biggio, Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Jeff Kent, Edgar Martinez, Fred McGriff, Mark McGwire, Mike Mussina, Mike Piazza, Tim Raines, Curt Schilling, Sammy Sosa, and Larry Walker. Should they not be elected to the Hall of Fame this year but receive at least five percent of the vote, McGwire would be facing his final year on the ballot in 2016 under the new rules, with time running out in similar fashion for Tim Raines.

The 17 first-time candidates are Rich Aurilia, Aaron Boone, Tony Clark, Carlos Delgado, Jermaine Dye, Darin Erstad, Cliff Floyd, Nomar Garciaparra, Brian Giles, Tom Gordon, Eddie Guardado, Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, Troy Percival, Jason Schmidt, Gary Sheffield, and John Smoltz.

The following two tables list the 34 candidates on the 2015 ballot, first the 23 position players, and then the 11 pitchers. They are ranked by their career Wins Above Replacement from Baseball Reference (bWAR) along with other representative qualitative statistics (explained below each table).

Here are the 23 position players on the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot, ranked by bWAR. First-time candidates are marked in bold italic.

| Position Players on the 2015 Baseball Hall of Fame Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Bonds, Barry |

.298/.444/.607 |

.435 |

162.4 |

164.0 |

182 |

173 |

| Bagwell, Jeff |

.297/.408/.540 |

.405 |

79.6 |

80.3 |

149 |

149 |

| Walker, Larry |

.313/.400/.565 |

.412 |

72.6 |

68.9 |

141 |

140 |

| Trammell, Alan |

.285/.352/.415 |

.343 |

70.4 |

63.7 |

110 |

111 |

| Raines, Tim |

.294/.385/.425 |

.361 |

69.1 |

66.4 |

123 |

125 |

| Martinez, Edgar |

.312/.418/.515 |

.405 |

68.3 |

65.6 |

147 |

147 |

| Biggio, Craig |

.281/.363/.433 |

.352 |

65.1 |

65.1 |

112 |

115 |

| McGwire, Mark |

.263/.394/.588 |

.415 |

62.0 |

66.3 |

163 |

157 |

| Sheffield, Gary |

.292/.393/.514 |

.391 |

60.2 |

62.4 |

140 |

141 |

| Piazza, Mike |

.308/.377/.545 |

.390 |

59.4 |

63.5 |

143 |

140 |

| Sosa, Sammy |

.273/.344/.534 |

.370 |

58.4 |

60.3 |

128 |

124 |

| Kent, Jeff |

.290/.356/.500 |

.367 |

55.2 |

56.4 |

123 |

123 |

| McGriff, Fred |

.284/.377/.509 |

.383 |

52.4 |

57.1 |

134 |

134 |

| Giles, Brian |

.291/.400/.502 |

.388 |

50.9 |

54.5 |

136 |

136 |

| Delgado, Carlos |

.280/.383/.546 |

.391 |

44.3 |

43.5 |

138 |

135 |

| Garciaparra, Nomar |

.313/.361/.521 |

.376 |

44.2 |

41.5 |

124 |

124 |

| Mattingly, Don |

.307/.358/.471 |

.361 |

42.2 |

40.7 |

127 |

124 |

| Erstad, Darin |

.282/.336/.407 |

.325 |

32.3 |

28.3 |

93 |

93 |

| Floyd, Cliff |

.278/.358/.482 |

.360 |

25.9 |

23.4 |

119 |

118 |

| Dye, Jermaine |

.274/.338/.488 |

.354 |

20.3 |

15.3 |

111 |

110 |

| Aurilia, Rich |

.275/.328/.433 |

.331 |

18.1 |

26.1 |

99 |

98 |

| Boone, Aaron |

.263/.326/.425 |

.327 |

13.5 |

9.8 |

94 |

93 |

| Clark, Tony |

.262/.339/.485 |

.352 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

112 |

109 |

wOBA: Weighted on-base average as calculated by FanGraphs. Weighs singles, extra-base hits, walks, and hits by pitch; generally, .400 is excellent and .320 is league-average.

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

OPS+: Career on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 OPS+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

wRC+: Career weighted Runs Created, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 wRC+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

For the position players, what emerges is a prime illustration of the logjam, at least based on this ranking by bWAR: Gary Sheffield muscles into the lower third of the dozen holdovers from the 2014 ballot, but the nine other first-time position players all fall into the bottom half of the table, and certainly the last half-dozen are making their only appearance on a Hall of Fame ballot.

On the other hand, at least they made the ballot. Left off the 2015 ballot are outfielder and first baseman Kevin Millar (.274/.358/.452), who in 12 seasons collected 1284 hits including 170 home runs and is probably best-known as a key member of the 2004 Boston Red Sox team that won its first World Series in 86 years; Mark Loretta (.295/.360/.395), a good-hitting, versatile infielder who in 15 seasons compiled 1713 hits including 309 doubles; Kelvim Escobar (101 wins, 96 losses, 4.15 ERA), a multipurpose right-handed pitcher who notched 38 saves in 2002 as a closer for the Toronto Blue Jays and 18 wins in 2007 as a starter for the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim; and Chad Bradford, who as a middle reliever would have dropped into Hall of Fame obscurity in any case but who did post a career 3.26 ERA and 138 ERA+ in 561 appearances totaling 515.2 innings pitched but is best-known as the distinctive right-handed submariner who emerges as one of the central figures in Michael Lewis's groundbreaking book Moneyball: The Art of Winning and Unfair Game, an "overlooked" and "undervalued" player integral to Oakland Athletics' general manager Billy Beane's strategy to win big on a small budget.

As for the lucky few who did make this year's ballot, Darin Erstad made a serious run in 2000 at George Sisler's single-season record of 257 hits when he banged out 240 knocks for the (then-) Anaheim Angels, with his .355 batting average runner-up to Nomar Garciaparra's American League-leading .372 (Sisler's record was subsequently broken by Ichiro Suzuki's 262 hits in 2004); Erstad caught the final out in Game Seven of the 2002 World Series against the San Francisco Giants for the Angels' first (and to date only) World Series victory, and Erstad is the only player in Major League history to win a Gold Glove as an outfielder and as an infielder. Cliff Floyd won a World Series with the 1997 (then-) Florida Marlins, although he was a bench player who had three plate appearances in that epic seven-game World Series; as an outfielder and designated hitter, Floyd had three seasons with 25 or more home runs and four seasons of 90 or more runs batted in, and he was a solid if unspectacular player. Jermaine Dye was another World Series winner—in fact, he was named the 2005 World Series Most Valuable Player when he batted .438 with one home run and three RBI to help the Chicago White Sox sweep the Houston Astros and clinch their first world championship in 88 years, with Dye driving in the only run in Game Four off Astros' closer Brad Lidge; in 14 seasons, Dye amassed 1779 hits, 363 doubles, 325 home runs, and 1072 RBI, a fine career but hardly exceptional.

Of the rest, Rich Aurilia was a good-hitting shortstop mainly for the San Francisco Giants who batted .324 when he led the National League in hits (206) in 2001, which also saw him hit a career-high 37 home runs (slightly overshadowed by teammate Barry Bonds's record-setting 73 round-trippers that year); Aurilia also hit the first grand slam ever in interleague play against the (then-) Anaheim Angels in 1997, admittedly no more than an interesting footnote in baseball history although I happened to have attended that game at Angel Stadium. Aaron Boone is part of the third generation of Boones to play major-league baseball—grandson of Ray, son of Bob, brother of Bret—and he is a descendant of 19th-century American pioneer Daniel Boone; as the New York Yankees' third baseman in 2003,Aaron Boone hit a home run off Tim Wakefield of the Boston Red Sox to start—and end—the bottom of the 11th inning of Game Seven of the American League Championship Series as that dinger sent the Yankees to the World Series; that is the crowning moment of Boone's pedestrian career. First baseman Tony Clark may be the tallest switch-hitter ever to have a sustained baseball career—he is listed at six feet, eight inches—but apart from his slugging 251 home runs over his 15-year career, including four years of 30 or more long flies, with two years of 100 or more RBI while just missing that plateau by one in 1999, his career is that of a solid but undistinguished journeyman; however, in one of his portrait photographs used on stadium Jumbotrons—I cannot recall whether it was when he was with the Detroit Tigers or the Arizona Diamondbacks—he looked like a werewolf. That was pretty neat.

We will discuss the other four first-time position players below. For now, here are the 11 pitchers on the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot, ranked by bWAR. First-time candidates are marked in bold italic.

| Pitchers on the 2015 Baseball Hall of Fame Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Pitcher |

W-L (S), ERA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

ERA+ |

ERA– |

FIP– |

| Clemens, Roger |

354–184, 3.12 |

140.3 |

139.5 |

143 |

70 |

70 |

| Johnson, Randy |

303–166 (2), 3.29 |

102.1 |

111.7 |

135 |

75 |

73 |

| Martinez, Pedro |

219–100 (3), 2.93 |

84.0 |

87.1 |

154 |

66 |

67 |

| Mussina, Mike |

270-153, 3.68 |

83.0 |

82.5 |

123 |

82 |

81 |

| Schilling, Curt |

216-146 (22), 3.46 |

79.9 |

83.2 |

127 |

80 |

74 |

| Smoltz, John |

213–155 (154), 3.33 |

69.5 |

78.7 |

125 |

81 |

78 |

| Gordon, Tom |

138–126 (158), 3.96 |

35.3 |

38.0 |

113 |

89 |

84 |

| Schmidt, Jason |

130–96, 3.96 |

29.6 |

37.5 |

110 |

92 |

85 |

| Smith, Lee |

71-92 (478), 3.03 |

29.6 |

27.3 |

132 |

76 |

74 |

| Percival, Troy |

35–43 (358), 3.17 |

17.5 |

11.7 |

146 |

69 |

86 |

| Guardado, Eddie |

46–61 (187), 4.31 |

13.7 |

8.1 |

109 |

92 |

97 |

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

ERA+: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA+ indicating a league-average pitcher, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

ERA-: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA- indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

FIP-: Fielding-independent pitching, a pitcher's ERA with his fielders' impact factored out, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 FIP- indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

Of the seven first-time pitchers, three are very auspicious and will be discussed in depth below. As for the other four making their debut on this ballot, Tom Gordon may have had the most memorable career. A runner-up to Gregg Olson as the 1989 American League Rookie of the Year (Kevin Brown and Ken Griffey, Jr., were also in contention), Gordon posted a 17–9 win-loss record with a 3.64 ERA as a spot starter and reliever for the Kansas City Royals; unfortunately, the Royals' attempt to make him into a starter proved unsuccessful, a situation perpetuated when he signed as a free agent with the Boston Red Sox in 1996. However, when Gordon became Boston's full-time closer in 1998, he led the AL in saves with 46, with 43 of those consecutive, and those 46 saves are still a single-season Red Sox record; meanwhile, he delivered a 7–4 record with an impressive 2.72 ERA—and an even more impressive 2.45 FIP and 173 ERA+—and allowing just two home runs in 79.1 innings pitched. But arm trouble that required Tommy John surgery in 2000 derailed him, and although he returned it was as a set-up and middle-relief man for a half-dozen teams before retiring. Still, Gordon, who at five feet, nine inches was hardly the archetypal looming figure on the mound, managed to play for 21 seasons (not counting his 2000 season missed because of injury), which is notable for a right-handed pitcher, and Gordon is to date the only major-league baseball player to figure prominently in a Stephen King novel (The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon).

It took a few seasons, first with the Atlanta Braves and then with the Pittsburgh Pirates, before Jason Schmidt got uncorked, and that only happened because of a mid-season trade in 2001 to the San Francisco Giants, where it is tempting to say that the pitcher-friendly dimensions of (now-) AT&T Park were conducive to the fire-balling right-hander who struck out at least 150 batters in six seasons, five of those consecutively, and who led the National League in ERA in 2003 with a 2.34 mark. That year, Schmidt was runner-up to Eric Gagné for the NL Cy Young Award, and he placed fourth in Cy Young voting the following year. But after signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2007, arm trouble dogged him, and Schmidt never recovered his form. He won 130 games in his career and struck out 1758 in 1996.1 innings pitched, but although the 16 (then-) Florida Marlins he struck out in a 2006 complete-game victory ties him with Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson for the most strikeouts by a Giants pitcher in a single game, that is as close to the Hall as Jason Schmidt will get.

Ninth all-time in saves with 358, Troy Percival enjoyed a nine-year run from 1996 to 2004 as the closer for the California/Anaheim Angels, saving at least 30 games per season during that time except in 1997 when he fell three short of that tier. Percival saved three games in the Angels' 2002 World Series victory in seven games over the San Francisco Giants, and during the 2002 regular season he posted a 4–1 win-loss record while recording 40 saves and a career-best 1.92 ERA. That ERA is a little deceptive, though, as Percival was always susceptible to the long ball: His FIP in 2002 was 3.03 as he allowed five home runs in 56.1 innings, and in fact the only run he allowed in three World Series innings was a solo homer to Barry Bonds in Game Two. In 708.2 regular-season innings, Percival allowed 85 home runs, or 1.1 per nine innings pitched, and although he was a strikeout pitcher—781 punch-outs, including 100 in just 74.0 innings in 1996, for an excellent 9.9 strikeouts per nine innings pitched ratio—his career FIP of 3.87 is significantly higher than his otherwise-outstanding 3.17 career ERA. In addition, Percival's lifetime total of 306 walks averages out to 3.9 walks per nine innings, which is balanced only by his excellent opponents' batting average of .188, and which translates to a manageable 1.108 WHIP (walks plus hits per innings pitched). Troy Percival was very good in his prime, but even without the Hall's bias against role players, his record hardly stands out as elite.

And as far as role players go, Eddie Guardado's career is emblematic of that. Starting his 17-year career with the Minnesota Twins, Guardado began as a starter in 1993, but when that did not work out (3–8, 6.18 ERA in 16 starts), he went into the bullpen, where he remained exclusively beginning in 1996, when he led the majors in appearances with 83 and solidified his nickname of "Everyday Eddie." Indeed, for an 11-year period from 1995 to 2005, the left-hander appeared in an average of 65 games per year, and in 2002 and 2003 the Twins tried him as their closer; he led the AL in saves with 45 in 2002 while notching 41 the following year. Signing as a free agent with the Seattle Mariners in 2004, Guardado did save 36 games in 2005 with a 2.72 ERA, his best earned run average in a season in which he pitched 50 or more innings. But despite the everyday reputation, Guardado had been beset by arm troubles throughout his career, and following a 2006 trade to the Cincinnati Reds, he began to be used as a LOOGY (Left-handed One-Out Guy) until his final season in 2009. You cannot play baseball, particularly in the contemporary game with its interventionist bullpens, without guys like Eddie Guardado, but as yet the Hall of Fame is hardly receptive to role players such as him.

The table below combines both position players and pitchers into a ranking by bWAR with their fWAR values also listed. First-time candidates are marked in bold italic.

| All 2015 Hall of Fame Candidates, Ranked by bWAR |

|||

| Rank |

Player |

bWAR |

fWAR |

| 1 |

Bonds, Barry |

162.4 |

164.0 |

| 2 |

Clemens, Roger |

140.3 |

139.5 |

| 3 |

Johnson, Randy |

102.1 |

111.7 |

| 4 |

Martinez, Pedro |

84.0 |

87.1 |

| 5 |

Mussina, Mike |

83.0 |

82.5 |

| 6 |

Schilling, Curt |

79.9 |

83.2 |

| 7 |

Bagwell, Jeff |

79.5 |

80.3 |

| 8 |

Walker, Larry |

72.6 |

69.0 |

| 9 |

Trammell, Alan |

70.3 |

63.7 |

| 10 |

Smoltz, John |

69.5 |

78.7 |

| 11 |

Raines, Tim |

69.1 |

66.4 |

| 12 |

Martinez, Edgar |

68.3 |

65.6 |

| 13 |

Biggio, Craig |

64.9 |

65.3 |

| 14 |

McGwire, Mark |

62.0 |

66.3 |

| 15 |

Sheffield, Gary |

60.2 |

62.4 |

| 16 |

Piazza, Mike |

59.2 |

63.6 |

| 17 |

Sosa, Sammy |

58.4 |

60.4 |

| 18 |

Kent, Jeff |

55.2 |

56.6 |

| 19 |

McGriff, Fred |

52.6 |

57.2 |

| 20 |

Giles, Brian |

50.9 |

54.5 |

| 21 |

Delgado, Carlos |

44.3 |

43.5 |

| 22 |

Garciaparra, Nomar |

44.2 |

41.5 |

| 23 |

Mattingly, Don |

42.2 |

40.7 |

| 24 |

Gordon, Tom |

35.3 |

38.0 |

| 25 |

Erstad, Darin |

32.3 |

28.3 |

| 26 |

Schmidt, Jason |

29.6 |

37.5 |

| 27 |

Smith, Lee |

29.6 |

27.3 |

| 28 |

Floyd, Cliff |

25.9 |

23.4 |

| 29 |

Dye, Jermaine |

20.3 |

15.3 |

| 30 |

Aurilia, Rich |

18.1 |

26.1 |

| 31 |

Percival, Troy |

17.5 |

11.7 |

| 32 |

Guardado, Eddie |

13.7 |

8.1 |

| 33 |

Boone, Aaron |

13.5 |

9.8 |

| 34 |

Clark, Tony |

12.5 |

12.5 |

Ranking the candidates by fWAR (the FanGraphs version) will alter the order to some degree but in most cases not enough to favor (or disfavor) a candidate significantly.

But who cares?

Seriously. Even cutting the ballot in two and concentrating on the top half will still leave more than ten Hall of Fame-caliber candidates, which is more than a voter can select on a ballot, anyway.

More significantly, though, and admittedly based on little more than the results from the past two years, I have come to the cock-eyed conclusion that ballot selection really resembles the seduction of women (the voters) by men (the candidates), and that the women (the voters) have already pre-judged the men (the candidates) and have placed them into groups of varying attractiveness.

So, with that metaphor in mind, let's look at the "men" in those groups.

Group One: The Hot Crushes

This group has the "men" that make "women" swoon. Pure and simple. These guys are the "front-door test," the guy whom your wife, girlfriend, significant other, plus-one, friend with benefits—whatever—would leave you for should he ever ring your doorbell and declare his desire for her.Last year, the hot crushes were Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux, and Frank Thomas, and voters fell hard enough for them to vote them into Cooperstown in their first year of eligibility.

This year, Randy Johnson and Pedro Martinez are definitely the hot crushes, and John Smoltz is probably one too. In 2011, I identified all three as "no-brainer" Hall of Fame selections, likely to be elected in their first year of eligibility, and I hate to say I told you so but the other two "no-brainers" I identified were Tom Glavine and Greg Maddux. (I did have Frank Thomas pegged as a "tough sell" Hall of Famer, but he proved to be not such a tough sell after all; good thing he never rang my doorbell.)

Even without having made their cases previously, even without seeing where they land in the table above, there isn't much that needs to be said for either Randy Johnson or Pedro Martinez and their qualifications for the Hall.

Randy Johnson is a tall, homely Brad Pitt with a mullet. He is probably the last man we will see in our lifetime reach 300 wins (unless Clayton Kershaw or Madison Bumgarner go on a prolonged tear), and even in this strikeout-rich environment we may never see another pitcher reach 4000 strikeouts. Pedro Martinez does not have those gaudy numbers, but this homely Johnny Depp in Jheri curls was a defiant David staring down a host of steroid-fueled Goliaths and simply mowing them down, one by one. Pedro's seven-year stretch from 1997 to 2003, right in the teeth of the Steroids Era, may be the most dominant stretch for any starting pitcher ever—and, yes, I know who Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Pete Alexander, Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Bob Feller, Warren Spahn, Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson, Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, Greg Maddux, and Roger Clemens are.

Meanwhile, John Smoltz is a versatile Bruce Willis (notice that I did not have to add homely) who won 213 games and saved 154 games, and even if he may not come off as big a front-door stud as Johnson or Martinez, just throw in those 3084 strikeouts—and those pretty impressive 8.0 strikeouts per nine innings and 3.05 strikeouts-to-walks ratios—and voters just may start to swoon. It is possible that Smoltz may have to wait until next year for Hall admission, but he won't have to wait long, hot crush that he is.

Group Two: The Plan-B's

Okay, so a woman (voters) may never get her hot crush—there is always the Plan-B guy, the guy who may not be as hot but is steamy enough to qualify as the fallback. On our ballot, that is still a select group.First up is Craig Biggio, top vote-getter in the bust that was the 2013 election and the top vote-getter again in 2014 among candidates not voted into the Hall. Boy, 74.8 percent of the vote. Can you say blue ball—well, never mind.

Biggio is one of many candidates on the 2014 whom I am sick of writing about, so I'll simply note that I presented his case as a Hall of Famer in 2013 and listed him seventh on my hypothetical ballot, and last year I had him listed again at the Number Seven spot.

Next is Mike Piazza, who has a touch of the bad boy about him (admitting to an early and brief use of PEDs) but otherwise is wholesome and desirable—he placed fourth in voting in 2013 with a respectable 57.8 percent, and he was the only non-elected candidate in 2014 besides Biggio to see an uptick in his voting percentage, collecting 4.4 percent more votes to nudge above the 60-percent line (although he didn't get the royal tease as did Biggio). I had Piazza listed at Number Eight on my hypothetical ballot in 2013 and again at that position in 2014. And back in 2011 Piazza was among my five "tough sells" as a Hall of Famer. (I didn't even bother profiling Biggio back then because I assumed he would be a shoo-in to the Hall. But you know what happens when you assume.)

Both Biggio and Piazza are attractive enough and fresh enough on the ballot to be Plan-B guys. But as for our next group . . .

Group Three: The Friend Zone

Guys, you know that when you are trying to seduce a woman, you have a window of opportunity in which to seal the deal—and if you don't make the impression sooner rather than later, you are going to wind up in the dreaded "friend zone."That is the case for our unfortunate fellows in this group. They are clean with respect to PEDs, they are—at least in my estimation—legitimate Hall of Famers, and some of them have made a decent showing on the ballot—but, unfortunately, they have already been on a few ballots and have not impressed voters sufficiently to garner that coveted 75 percent.

Foremost in this group is Jeff Bagwell, who in four rounds on the ballot has yet to crack 60 percent of the vote, although he came close in 2013 with 59.6 percent. Bagwell is one guy I'm getting tired of writing about because I wrote about him as a Hall of Famer in my very first article for this site. In 2014, I had Bagwell listed fourth on my ballot; in 2013, I had him tagged at Number Three; and even though I did not do a ranking in 2012, Bagwell was one of the eight I would have voted for.

Next up is Larry Walker, who has yet to do better than 22.9 percent in four years on the ballot. Walker is another one whose case I stated in my first article, again in my unranked assessment in 2012, and who placed sixth in my 2013 ranking, and ninth in my 2014 ranking. Edgar Martinez is another one who is not turning enough voters' heads. In five ballot tries Martinez has done better than Walker, polling in the low- to mid-30-percent range in his first four ballots although he dropped 10.7 percent last year; he was among my eight in 2012, I had him ranked 11th in 2013 and ranked 13th in 2014.

And while he is coming up on just his third ballot appearance, Curt Schilling may have already passed into the friend zone. I did anticipate that Schilling would be a "tough sell" as a Hall of Famer, but his 38.8 percent on his first ballot was surprisingly disappointing (I had him ranked at fourth place on my ballot), and he dropped nearly ten points on last year's ballot (I had him ranked fifth on that ballot).

Group Four: The Bad First Impressions

Even though you've combed your hair, checked your breath, checked your fly, tried to come up with your most sincere opening line, and smiled as you approached her, sometimes you just don't make that good a first impression on a woman. That seems to be the case for our two poor saps here.Perhaps that is not too surprising in the case of Jeff Kent: At first glance he is a borderline case (he is the fourth of my five "tough sells"), I had him ranked 15th on my ballot for 2014, his first year on the ballot, and in fact Kent grabbed only 15.2 percent of the vote.

But that overstuffed ballot is a great leveler. Even though Mike Mussina was the last of my five "tough sells," and I could rank him no higher than 14th on my 2014 ballot, he has a much stronger case than does Kent, and perhaps his 20.3 percent of the vote on his inaugural ballot is just another example of too many choices to fill too few slots.

Group Five: The Freaks

You knew the PEDs boys had to land somewhere, and here they are: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Mark McGwire, Gary Sheffield, and Sammy Sosa. Jeff Bagwell is sometimes cast into this group, but unlike the others, there is no material evidence to merit his inclusion.In eight years on the ballot, McGwire has failed to impress a full quarter of the voters—his best showing was 23.7 percent in 2010—and if he does not get elected this year, he has one more chance under the new rules before being removed permanently. I wouldn't hold my breath, but I did call McGwire a Hall of Famer in 2012, again in 2013—although he didn't make the top ten that year—and again in 2014, although he dropped to 17th place among the 18 players I thought were Hall-worthy.

Sosa, I will admit, has been at the tail-end of my picks for the Hall, 14th of 14 in 2013 and 18th of 18 in 2014, and with a mere 7.2 percent of the vote in only his second ballot last year, a 5.3 percent drop from his premiere in 2013, he may in fact fail to get five percent of the vote this year and thus become the first eligible candidate with 600 or more career home runs to lose his bid for the Hall of Fame. That would be a dubious capper to an already-controversial career.

Of course, some women like the bad boys: Both Clemens and Bonds have managed to impress about a third of the voters in the two years they have been on the ballot. Both of course are ridiculously overqualified for the Hall of Fame. I ranked Clemens at Number Two on the 2013 ballot, and at Number Three on the 2014 ballot. Bonds topped my 2013 ballot, and was at the second slot in 2014.

Sheffield is making his first appearance on a Hall of Fame ballot this year; as a borderline candidate I profiled him in depth just recently, and although I concluded that he falls just below the threshold, it will be his being named in the Mitchell Report—and his association with Bonds and the Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative (BALCO) scandal—that will be the Scarlet Letter that will turn off voters.

Group Six: The Geeks

You know who these guys are—women may respect them for their skills and abilities, but they are hardly sex symbols and generally do not merit a first look, let alone a second, in that department. Such is the case with sabermetric darlings Tim Raines and Alan Trammell, whom the stat-crunchers have been touting as Hall of Famers but to most voters their secret numbers are just that—secret. Others may say that they are qualified, but they just don't look like it.Sure, some women like the nerdy type—after all, both Raines, on his eighth ballot, and Trammell, on his fourteenth, have managed to attract enough votes to stay eligible. Raines has had a better time of it, having gone from about a quarter of the vote to roughly half. Trammell has worked his way up from about 16 percent on his first time out to a third of the vote in 2013 before dropping down to around 20 percent last year, and this is after being on the ballot for nearly twice as long as Raines. Raines does have one gaudy statistic—he is fifth all-time in stolen bases with 808. But after all this time, and on such an overstuffed ballot, both would be happy just to make it to the Friend Zone—at least that would tell them that they really do exist.

Both Raines and Trammell got my hypothetical vote in 2012. In 2013, Raines was at Number Five on my ballot, and in 2014 I put him at Number Six, while for Trammell, he was at the Number Ten spot both in 2013 and in 2014. Yes, I'm a geek too.

However, as I will explain below, my voting strategy this year (were I to have a ballot) has changed, and as part of that change I would not vote for either one. Not that I think that they are no longer Hall of Famers, but that they do not make the top ten. This really hurts with respect to Raines, whom I had pegged as a Hall of Famer (albeit a borderline one) all the way back in 2002, in his final year as a player.

Group Seven: The Nice Guys

Although it's true that these nice guys are not actually finishing last (and leaving aside that Leo Durocher's deathless observation had been misquoted from the start), they are hardly at the front of the line, and like the Geeks, they would be happy just to make it to the Friend Zone.In this group are ballot old-timers Don Mattingly and Lee Smith, ballot veteran Fred McGriff, and ballot rookies Carlos Delgado, Nomar Garciaparra, and Brian Giles.

I have written recently about Delgado and Garciaparra as borderline candidates on this year's ballot, and how each does not rise to the level of a Hall of Famer.

As for Giles, superficially, he looks surprisingly viable. He came pretty close to a classic (and Hall of Fame-worthy) 3-4-5 slash line, reaching two-thirds of that with a .400 on-base percentage and a .502 slugging percentage with only his batting average falling short—although not many hitters would complain about a .291 average over the course of their career. And in a free-swinging era in which hitters are unfazed by high strikeout totals, Giles walked about 350 more times than he fanned, leading the National League in walks (119) in 2005, the same year he finished with his only top-ten showing in Most Valuable Player voting; Giles walked 1183 times in his career while striking out just 835 times in 6527 career at-bats. And as his .502 slugging average suggests, Giles wasn't a banjo hitter—he finished with 411 doubles (163rd lifetime, and just ahead of Hall of Famers Mike Schmidt and Ernie Banks), 55 triples, and 287 home runs (152nd all-time), while he had a four-year peak in that department as he hit at least 35 home runs from 1999 to 2002.

But Giles had neither a dominant peak nor substantial counting numbers—his 1897 hits are 326th all-time, just behind Royce Clayton—and like Delgado, Garciaparra, Mattingly, McGriff, and Smith, he posted an excellent record but one that falls short of the Hall. Not last, but hardly first, either.

Group Eight: The Nonentities

This group rounds up everyone else on the 2015 ballot who has not been mentioned yet.These are the guys who women vaguely suspect exist but do not think twice about although one or two may "sign the yearbook" with "have a great summer!" or in other words, a voter may cast the hometown vote for the candidate. However, on an overstuffed ballot such as this one, they might not even get that one vote.

My 2015 Hall of Fame Ballot (If I Had One)

Were I to be a Baseball Writers' Association of America member with the privilege to cast a Hall of Fame ballot, my strategy this year would be to clear the ballot. Plain and simple. That means voting for the universally obvious Hall of Fame candidates and the candidates who I think are obvious Hall of Famers even if many voters do not—and I would cast a couple of "protest" votes besides.Ten votes maximum, and in my view more than ten qualified candidates. For the record, I think there are 17 qualified Hall of Famers, which is a small victory as I counted 18 last year. Three of them were elected, and one did not receive the five percent minimum required to stay on the ballot; this year, only three first-time candidates qualify.

So, in reverse order, here are my ten choices:

10. Larry Walker (fifth year on the ballot)

To me, Larry Walker is an obvious Hall of Fame right fielder. Jay Jaffe's JAWS system places him 10th among all right fielders all time, with the nine players above his ranking all Hall of Famers, and three of the four ranked just behind him also Cooperstown residents, with one, Joe Jackson, sure to have been voted into the Hall had not his gambling notoriety precluded that. Walker's bWAR, WAR7 (his seven best season by bWAR; they do not have to be consecutive), and JAWS (a blended computation based on career bWAR and WAR7) are right at the average for the 24 right fielders already in the Hall of Fame.

As for Coors Field, Walker's home field while he was with the Colorado Rockies, get over it. Yes, all but two of his nine-plus seasons there were before the Rockies began using a humidor to store baseballs and thus counter the effects of altitude, although it is actually the dry air—not the thin air—that was as much to blame for unusual ball travel. (Dry air hardens balls and makes the transfer of kinetic energy from a swung bat more efficient at the moment of impulse, or impact, and thus propels them farther. The humidor softens balls with moisture and makes them less elastic, decreasing impulse efficiency and thus reducing ball travel. See? Geek. Call me, ladies.)

In any case, Walker played 30 percent of his home games overall at Coors, and of the 49 home runs he hit in 1997—before the humidor was in use—29 of those dingers were hit on the road. The follow-on effect to the perception of an unfair home-field advantage enjoyed by Walker, if that is what the resistance is here, is how Todd Helton, who played his entire career with the Rockies (albeit the majority of it after the humidor was introduced), will fare when he first lands on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2019.

9. Mike Piazza (third year on the ballot)

Look, Mike Piazza is the best-hitting catcher in Major League history, and considering his surprisingly good showing on two ballots already, let's just elect him and clear space on the ballot. Jaffe's JAWS ranks Piazza fifth all-time among catchers, and of the top eight, only Ivan Rodriguez, who is not even eligible for the Hall until 2017, is not in the Hall yet.

Unless those "women" suddenly get second thoughts about their Plan-B guy and now consider him to be a bad-boy Freak. If that's the case, then we are in real trouble with respect to the ballot.

Oh, perish the thought. Although I have now thrown it out into the cosmos. . . .

8. Mike Mussina (second year on the ballot)

An indication of how saturated this ballot is, Mike Mussina comes in at Number Eight on my ballot. Mussina is ranked 28th all-time among starting pitchers by JAWS, keeping in mind that there are 59 starting pitchers enshrined in the Hall of Fame, and last year's first-ballot crush Tom Glavine is ranked 30th.

Falling 30 wins shy of 300, with a 3.68 ERA, Mussina will be more of a Bert Blyleven than a Glavine, although Blyleven at least had two top ten rankings among his counting numbers (fifth in strikeouts with 3701, and ninth in shutouts with 60), and Blyleven was on less-crowded ballots than is Mussina. Still, who would you rather pitch a big game for you, Hall of Famers Burleigh Grimes, Early Wynn, or Rube Marquard? Or Mike Mussina? Yeah, I'd hand the ball to Moose too.

7. Craig Biggio (third year on the ballot)

Another example of the overstuffed ballot: Craig Biggio is a 3000-hit guy; he got those hits cleanly; only he, Ty Cobb, and Tris Speaker have ever combined at least 3000 hits, at least 600 doubles, at least 400 stolen bases, and at least 1800 runs scored in a career—and I have to place him seventh on a ballot?

Maybe we can blame JAWS for this one, as Biggio is ranked 14th all-time among second basemen. On the other hand, there are 19 second sackers in the Hall, and even if Biggio's JAWS scores are about four wins behind the aggregate average, he still ranks ahead of Bobby Doerr, Nellie Fox, and Tony Lazzeri, let alone Johnny Evers, Red Schoendienst, and . . . Bill Mazeroski?

6. Curt Schilling (third year on the ballot)

In some ways, Curt Schilling is another Mike Mussina. JAWS ranks Schilling 27th all-time among starting pitchers, just ahead of Mussina. In one way, Schilling falls behind Mussina: With 216 career wins, Schilling is 54 wins behind Mussina on the career wins list, exactly 20 percent fewer than Moose.

If wins are any indication of how good a pitcher is, that is—and I've argued previously that they are not. What matters more is run prevention, and Schilling was Hall of Fame-good in that department. His 3.46 ERA is excellent in his high-offense era, but his 3.23 FIP is even more telling. Schilling may have been susceptible to the long ball—his career 347 home runs allowed is tied for 28th all-time (Mussina's 376 is 18th all-time, by the way)—but with respect to the other two True Outcomes that drive FIP, walks and strikeouts (home runs being the third), Schilling is almost without peer. Schilling walked only 711 in 3261.0 innings for a stingy 2.0 walks per nine innings, and he struck out 3116 (15th all-time) for a gaudy 8.6 strikeouts per nine innings—but that is nothing compared to his insane 4.38 strikeouts-to-walks ratio, the best mark in the live-ball era, which began nearly a century ago.

And you want big-game pitcher? His performances in the 2001 World Series, which got him named Series co-MVP with Randy Johnson, and the legendary "bloody sock" in the 2004 American League Championship Series, go without saying, but we tend to forget that Schilling, although he got tagged for the loss in the opening game of the Philadelphia Phillies' 1993 World Series against the Toronto Blue Jays, pitched the Phillies to their second victory in Game Five with a gem, a five-hit shutout that—don't forget—came on the heels of the Phillies' collapse in the previous game when, leading 14 to 9, they gave up six runs in the eighth inning as the Jays nipped them in a wild win. Schilling made that Series closer than it could have been.

I'd stated above that for a big game I'd hand the ball to Mike Mussina over any number of pitchers already in the Hall of Fame. But if Curt Schilling were available, he'd get the nod with no second thought. That's Hall of Fame-good.

5. Jeff Bagwell (fifth year on the ballot)

While Hot Crush Frank Thomas got elected in his first year last year, Jeff Bagwell is still awaiting his turn on this, his fifth ballot. JAWS ranks Bagwell as the sixth-best first basemen all-time while Thomas is ranked ninth-best, and every eligible first baseman in the top 12 has been elected to the Hall of Fame except for Rafael Palmeiro, and we know what his problem is.

So, with Bagwell, it's put-up-or-shut-up time: If there is any evidence that Jeff Bagwell used performance-enhancing drugs, let's see it. Otherwise, there is no reason why he should not be elected to the Hall.

4. Roger Clemens (third year on the ballot)

This is first of my two "protest" votes. I sincerely doubt that the voting writers will, collectively and telepathically, decide that Roger Clemens, along with Barry Bonds, has been "punished" enough, and that they will then vote for him (and Bonds) in sufficient numbers to elect him to the Hall.

And I'm not going to go into yet another discourse about the murky environment of PEDs, their alleged effects, and equally nebulous rules and penalties prior to a consensus being reached by the mid-2000s. Nor am I going to split hairs once more about whether Clemens would have been a Hall of Famer before he most likely began using PEDs.

I will simply note that at least by JAWS rankings for starting pitchers, Roger Clemens ranks third. At some point in the future, provided that he (or Bonds) are not elected to the Hall, fans will wonder why so many players at or near the top of the leaderboards are not in the Hall of Fame. Baseball will need to answer that, but my suspicion is that there is no way to respond without looking like the Morality Police.

3. Barry Bonds (third year on the ballot)

This is the second of my "protest" votes.

Barry Bonds ranks first all-time among JAWS rankings for left fielders. By the way, Pete Rose ranks fifth among all left fielders.

What does it say about Major League Baseball that its all-time leader in hits, Pete Rose, is not in the Hall of Fame and never will be barring a reversal in policy, and that its all-time home run leader, Bonds, may never be voted in despite being eligible—and ridiculously over-qualified?

We can blame the individual all we want, scold them for making poor decisions, and in the case of Bonds, withhold a merit privilege as a way to punish bad behavior. But neither Bonds nor Rose created the environment in which they performed. That environment is the institution of baseball, and at some point that institution is going to have to take responsibility either for attracting reprobate players such as Bonds or Rose (and many more like them throughout its history) or for creating or fostering the environment in which they became reprobates—if indeed "reprobate" is what they are.

Baseball is hardly a wholesome and innocent institution; it never has been. From its inception, it has fostered gambling, collusion, discrimination, racism, and anti-labor practices while trying hard to paint itself as a fundamental slice of Americana, its "national pastime."

Arguments pointing this out, and I've made a few, are as tiresome as the reasons for the arguments in the first place. As Dan le Batard pointed out with his protest ballot last year, the Hall of Fame has become the Hall of Morality, promoting an illusion instead of reality, and that reality is that PEDs happened—is still happening despite the increased vigilance and penalties—and that baseball collectively was slow, even reluctant, to address the issue. Now, through the BBWAA Hall of Fame vote, it is applying its punishment retroactively.

And Dan le Batard was punished merely for protesting that.

2. Pedro Martinez (first year on the ballot)

Pedro Martinez is ranked 21st by JAWS among starting pitchers all-time. He is worth about 10 wins more than the average bWAR and JAWS ratings of 59 pitchers already in the Hall of Fame.

It is possible that with "only" 219 wins (against only 100 losses for an elite .687 winning percentage in any case), Martinez may not look like a Hall of Famer, or at least a first-ballot one, to a number of voters. But for those voters not trapped in the 20th century, the ones who realize that wins are a team effort and that in an age of interventionist bullpens it is harder for a starting pitcher to get the "win," and who understand that run prevention is a much more accurate measure of a pitcher's effectiveness, they may instead notice that:

1. Martinez's 2.93 ERA is exceptional for his era. Neither first-ballot pitcher last year, Tom Glavine and the sublime Greg Maddux, has a career ERA under 3.00 (and Glavine's 3.54 ERA is much closer to Mike Mussina's).

2. Martinez's FIP is 2.91, actually just a bit better than his ERA. That is not surprising as he allowed just 239 home runs in 2827.1 innings pitched, just 760 walks for an outstanding 2.4 walks allowed per nine innings, and struck out 3154 batters (13th all-time) for a remarkable 10.0 strikeouts per nine innings while his unreal strikeouts-to-walks ratio of 4.15 is second only to Curt Schilling's in the live-ball era.

3. Martinez's ERA+ of 154 is second only to Mariano Rivera's 205—and Martinez accomplished that in more than twice the innings pitched by Rivera.

1. Randy Johnson (first year on the ballot)

Randy Johnson is ranked ninth by JAWS among starting pitchers all-time. Of the top 25 pitchers on that list, only Roger Clemens, Pedro Martinez, and 19th-century dead-ball pitcher Jim McCormick are not yet in the Hall of Fame.

Do we really need to examine Johnson's qualifications?

"It Was Broke, So We Fixed It." Or Did We?

Last year, I closed by speculating whether, in the wake of no candidates having been elected in 2013, the Hall of Fame voting process was broken. If it was, I listed a number of approaches the Baseball Hall of Fame might take to remedy the situation.Intriguingly, one that I did not specify is one that the Hall introduced for balloting this year and for subsequent ballots: Shortening the maximum term a candidate may remain on a ballot from fifteen years to ten years. As I noted previously, this "remedy" is a short-term one that ultimately puts the burden of deciding about "problematic" candidates in the hands of the Expansion Era Committee—and as we have seen just recently with the election held by this committee's sister committee the Golden Era Committee, it elected no candidates from the Golden Era. So, in essence, the writers have had their gatekeeping function reduced.

However, last year's vote showed that the process was not broken completely. The BBWAA voters did elect three candidates, only the seventh time since 1937 that the writers have elected as many as three candidates in a single year. That is the good news; the unspoken message, though, was that with last year's election of first-time-eligible candidates Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux, and Frank Thomas, voters have a bias toward candidates without even the slightest hint of a connection to performance-enhancing drugs—and in the case of Thomas, that candidate had been outspoken about his opposition to PEDs. (As has Curt Schilling, although we'll open that can of worms some other time.) This stance was reinforced by the lack of support for Rafael Palmeiro, only the fourth man to collect at least 3000 hits and 500 home runs, but who failed to collect at least five percent of the vote in 2014 and was thus removed from the 2015 ballot.

But despite the Hall's rule change and the continuing moralism concerning PEDs, the issues of the ballot logjam and of players associated with PEDs may have been swept under the rug temporarily but they are still evident by their conspicuous lumps on the floor. Perhaps the best we can expect from the BBWAA's voters this year is to elect as many qualified candidates as possible.

And despite reports of voters (such as ESPN's Buster Olney) who will be submitting blank ballots signifying varying stances or protests, I am optimistic that there will be a few elected candidates. I am not optimistic that they will be any Friend Zones or Bad First Impressions, let alone any Freaks or Geeks, but even electing Hot Crushes and Plan-B's will alleviate the ballot logjam to a small extent.

And although predictions are usually little more than SWAGs (Silly Wild-Ass Guess), here are mine:

3. Craig Biggio (84.3 percent)

2. Pedro Martinez (91. 7 percent)

1. Randy Johnson (98.6 percent)

Or to rework the famous observation made by Hall of Fame shortstop Ernie Banks, it's a great day for a Hall of Fame election—let's elect a few more! There are certainly plenty of candidates from whom to choose.

Comments powered by CComment