Making It Harder to Be Elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame

No one is begrudging the election of Glavine, Maddux, and Thomas—and for Maddux, one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history, not to have been elected on his first ballot would have indicated a fundamental problem with the election process—but it did little to alleviate the logjam of qualified candidates not just on the current ballot but on ballots for upcoming years.That is why, in an effort to alleviate that logjam, the Hall of Fame announced in July 2014 that the term of eligibility for a player on the ballot has been reduced from 15 years to 10 years, provided that the player receives at least five percent of the vote in any given year to remain on the ballot. (Candidates currently at or beyond that ten-year limit are grandfathered and will leave the ballot only if they are elected, cannot maintain at least five percent of the vote, or reach their 15th year without election.)

Thus, it will be even harder for a player to get into the Hall of Fame: There is already a surfeit of qualified players on the ballot, and in the age of talent compression baseball has been in for the last two decades—there have been many outstanding players, making it difficult for most players to be truly dominant and stand out as being Hall of Famers—more will be added to that overstuffed ballot in upcoming years. And now, once on that ballot, the annual opportunity to be elected to the Hall of Fame has been reduced by one-third.

Feeling that restriction even more keenly are those players "on the bubble," the ones whose legacies are on the cusp of immortality, at least as determined by the voters of the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA), whose votes elect the candidates to the Hall, and whose names, starting with the next ballot, will be made public even if their votes will not. (Individual voters may voluntarily divulge that information, and in fact many have been doing so for quite some time.) Those borderline players may find their fate is in the hands of the Expansion Era Committee once their time on the ballot is through.

But it is those players "on the bubble" that are of real interest, as they form that threshold between players defined as one of the greatest who ever played—those in the Baseball Hall of Fame—and all the other players, and that is our focus here: examining players eligible for the Hall in the next five years, many of whom were high-profile players, some of whom seem as if they could be Hall of Fame-caliber players, and some of whom may actually be Hall of Fame-caliber players.

Locks and Lock-outs: Players Not under Detailed Discussion Here

So, we will not be discussing the following players expected to appear on ballots between 2015 and 2019 as they are almost certainly going to be elected to the Hall of Fame during their tenure on the ballot:2015: Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, John Smoltz

2016: Ken Griffey, Jr.

2018: Chipper Jones, Jim Thome

2019: Roy Halladay, Mariano Rivera

Way back in 2011, I identified Johnson, Martinez, and Smoltz as "no brainers" with respect to their being elected to the Hall of Fame. Similarly, two members of the 600-home run club, Griffey, Jr., and Thome, earned their distinction "the right way," and Griffey, Jr., elected in 1999 to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team (only one of four active players to be elected), is particularly likely to be a first-ballot inductee; Thome, though, may not have the same cachet, as I noted in 2011 as he was approaching the 600-homer milestone with a relative lack of fanfare. Jones is the greatest switch-hitter in baseball history not named Mickey Mantle or Pete Rose, and is certainly the greatest switch-hitting third baseman of all time. Rivera, universally regarded as the greatest relief pitcher of all time, is another candidate practically guaranteed to be elected on his first ballot, and while Halladay's record may not have the standout numbers of Johnson or Martinez, for his time he was one of the most dominant starting pitchers and will most likely receive sufficient attention to be elected without much contention. (I made the case for Halladay in 2013 in an examination of pitching wins and the Baseball Hall of Fame.)

We are also not discussing, at least in great detail, Manny Ramirez, putatively eligible in 2017. On his batting record alone, Ramirez may be the greatest right-handed hitter of his era—sorry, Frank Thomas—and is one of the greatest hitters of all time, with a .312/.411/.585 slash line (batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage), yielding a .996 OPS (on-base plus slugging percentage) and a 154 OPS+ (OPS league- and park-adjusted and indexed to 100, with 100 being league-average; Ramirez ranks 25th all-time in this category). In 2302 games and 9774 plate appearances, Ramirez banged out 2574 hits and slugged 547 doubles (28th all-time) and 555 home runs (14th all-time) while scoring 1544 runs and driving in 1831 (18th all-time). He helped lead the Cleveland Indians to two World Series (1995 and 1997), and he helped lead the Boston Red Sox to World Championships twice, first in 2004, in which he was named the Series' Most Valuable Player, and again in 2007.

But Ramirez is another poster child for PEDs. His name was alleged to have been in the Mitchell Report, the findings of the committee headed by former Senator George Mitchell that investigated the issue of PEDs in baseball, and although Ramirez's name ultimately did not appear in the report, two subsequent incidents have tarnished—perhaps irrevocably—Ramirez's image: In 2009, he endured a 50-game suspension after testing positive for taking a women's fertility drug, human chorionic gondatrophin (hCG), reputed to be used to restart testosterone production following a steroids cycle. The 50-game suspension was the first punishment in Major League Baseball's then-current drug policy of "three strikes and you're out," in which the third violation meant a permanent ban from the sport. The punishment for the second violation was a 100-game suspension, which Ramirez incurred in 2011 when he failed another drug test—but instead of serving the suspension, Ramirez abruptly retired. Months later, wishing to be reinstated, he agreed to a negotiated 50-game suspension, and he even signed with the Oakland Athletics in 2012 although he did not play with them before being released.

Since then, Ramirez has tried to return to baseball, possibly clouding when he may actually be eligible for the Hall of Fame ballot. However, considering that his drug violations followed the "Wild Wild West" ambiguities of the sport's attitude toward doping in the late 1990s and early 2000s and occurred when there was a definite policy structure in place, Ramirez seems certain to face considerable opprobrium for some time to come. Manny Ramirez's only hope may lie with an Expansion Era Committee many years hence.

Also not under detailed discussion is Ivan Rodriguez, although his case is hardly as egregious as Ramirez's. Getting the ugly part out of the way, Jose Canseco, in his 2005 notorious tell-all book Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant 'Roids, Smash Hits & How Baseball Got Big, identifies Rodriguez as getting anabolic steroids injections from Canseco himself. Asked about the allegations, Rodriguez replied that he was "in shock," and when, four years later, he was asked whether his name would appear in the Mitchell Report, Rodriguez replied, "Only God knows."

Not exactly vociferous denials, but on the other hand, no other allegations, let alone evidence, have yet emerged to implicate Rodriguez with PEDs. So, when he becomes eligible in 2017, if the PEDs allegations don't sully his chances, there is little else to keep him from the Hall of Fame.

Both offensively and defensively, Ivan Rodriguez is one of the greatest catchers in the game's history, on a par with Johnny Bench, Yogi Berra, and very few others; Jay Jaffe's JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score system) rating, which uses Baseball Reference's version of Wins Above Replacement (WAR) to rank players against existing Hall of Famers, places Rodriguez third, behind only Bench and Gary Carter. In 2543 games and 10,270 plate appearances, he racked up 2844 hits including 572 doubles and 311 home runs for a .296/.334/.464 slash line, generating a .798 OPS and a 106 OPS+; he scored 1354 runs while driving in 1332, and he managed to steal 127 bases.

Although Rodriguez established an outstanding batting record, it was his defensive ability that truly distinguished his career as a catcher. He is the lifetime leader in games started as a catcher (2346) and in putouts for a catcher (14,864), and he is fifth in double plays turned as a catcher (158), 23rd in career assists (1227), and 39th in base runners caught stealing (661), while his caught-stealing percentage of 45.68 is the best of all catchers during his playing career. Not surprisingly, Rodriguez ranks eighth in defensive WAR with 28.7, leading all catchers.

In sum, Ivan Rodriguez is the proverbial "first-ballot Hall of Famer," not only one of the best players at his position during his playing career but one of the very best ever to play that position. Only the PEDs taint could prevent "Pudge" from sailing into the Hall of Fame.

Hall Voting As a Referendum on PEDs

And at this point, it should be crystal-clear that Hall of Fame voting is a de facto referendum on performance-enhancing drugs, as underscored by the votes in 2013 and 2014. In 2013, voters allocated only a fraction of their votes to Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, each of whom on numbers alone ranks as the very best at his respective position. If other candidates with PEDs associations—Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and others—were not elected, arguments about not including them that did not involve PEDs (at least directly) had some credibility. Not so with Clemens and especially with Bonds.The 2014 vote did elect three players—and each of whom were repudiations of the PEDs era. Glavine and Maddux were both pitchers who worked by guile; neither was a power pitcher, although Maddux did surpass the 3000-strikeout milestone. And as finesse pitchers who battled the bulked-up hitters of the Steroids Era, they both reinforced the David Versus Goliath imagery of the time. And although Thomas, a tight end at Auburn, looked like a Goliath, the "Big Hurt" was actually one of the most vociferous advocates for drug testing, and not only did he decry those players who used PEDs, he insisted that his career was played "the right way"—cleanly, with no chemical or biological help.

It is significant that all three, exemplars of PEDs cleanliness, leapt over all the existing candidates on the ballot and into Cooperstown ahead of them. Even more significantly, Rafael Palmeiro in 2014 fell off the ballot in only his fourth year on it. In 2005, Palmeiro denied while under oath to a Congressional hearing on PEDs that he had ever taken any PEDs—only to test positive for the anabolic steroid stanozolol months later and be suspended for 10 days.

Palmeiro is only the fourth hitter in Major League history to collect at least 3000 hits and at least 500 home runs in his career. The other three were Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Eddie Murray, and all three were elected in their first year of Hall eligibility. Palmeiro's best showing was in 2012, his second year on the ballot, when he scraped together 12.6 percent of the ballot. It's not as if the novelty of being a member of the exclusive 3000-hit, 500-homer club has worn off—it's Palmeiro's fatal association with PEDs that has doomed him.

Indeed, a candidate needs only have the presumption of having used PEDs to sully his chances. Jeff Bagwell has never been tied to any evidence that he used illegal substances, but he has struggled to reach the 75-percent threshold since his first appearance on the ballot in 2011. And it has been suggested that Craig Biggio's failure to be elected in two tries on the ballot may be tied to his being Bagwell's Houston Astros teammate from 1991 to 2005—a case of guilt by association following guilt by presumption.

Evaluating the Borderline Candidates

So, in evaluating candidates slated to appear on the next five ballots, from 2015 to 2019, we will dispense with players expected to be elected even on an overstuffed ballot and with players whose association with PEDs is so pronounced that it will very probably sully the player's chances for the Hall even with ironclad credentials. Well, as you will see below, there are two players evaluated who are tainted with the PEDs brush but whose credentials divorced from that still put them at the borderline.In this two-part series, the players we will evaluate, by year of eligibility, are:

2015: Carlos Delgado, Nomar Garciaparra, Gary Sheffield

2016: Garret Anderson, Jim Edmonds, Trevor Hoffman, Billy Wagner

2017: Vladimir Guerrero, Magglio Ordonez, Jorge Posada, Edgar Renteria

2018: Johnny Damon, Andruw Jones, Jamie Moyer, Scott Rolen, Omar Vizquel

2019: Lance Berkman, Todd Helton, Roy Oswalt, Andy Pettitte, Michael Young

In Part One of this series, we will examine the 11 candidates slated to be on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot for the next three years, from 2015 to 2017. However, for comparative purposes for all five years, we will look briefly at the relative value of all 21 players.

The following two tables list these 21 upcoming candidates for the next five ballots who are on the borderline for the Hall of Fame, 16 position players and 5 pitchers. They are ranked by their career Wins Above Replacement from Baseball Reference (bWAR) along with other representative qualitative statistics (explained below each table).

Here are the 16 position players, ranked by bWAR. Players under discussion in this article are in bold.

| Position Players , Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Rolen, Scott |

.281/.364/.490 |

.368 |

70.0 |

69.9 |

122 |

122 |

| Jones, Andruw |

.254/.337/.486 |

.352 |

62.8 |

67.6 |

111 |

111 |

| Helton, Todd |

.316/.414/.539 |

.405 |

61.5 |

55.3 |

133 |

132 |

| Edmonds, Jim |

.284/.376/.527 |

.385 |

60.3 |

64.0 |

132 |

132 |

| Sheffield, Gary |

.292/.393/.514 |

.391 |

60.2 |

62.4 |

140 |

141 |

| Guerrero, Vladimir |

.318/.379/.553 |

.390 |

59.3 |

56.5 |

140 |

136 |

| Damon, Johnny |

.284/..352/.433 |

.344 |

56.0 |

42.9 |

104 |

105 |

| Berkman, Lance |

.293/.406/.537 |

.400 |

51.8 |

55.5 |

144 |

144 |

| Vizquel, Omar |

.272/.336/.352 |

.310 |

45.3 |

42.0 |

82 |

83 |

| Delgado, Carlos |

.280/.383/.546 |

.391 |

44.3 |

43.5 |

138 |

135 |

| Garciaparra, Nomar |

.313/.361/.521 |

.376 |

44.2 |

41.5 |

124 |

124 |

| Posada, Jorge |

.273/.374/.474 |

.367 |

42.7 |

44.9 |

121 |

123 |

| Ordonez, Magglio |

.309/.369/.502 |

.375 |

38.5 |

37.8 |

125 |

126 |

| Renteria, Edgar |

.286/.343/.398 |

.327 |

32.1 |

35.5 |

94 |

95 |

| Anderson, Garret |

.293/.324/.461 |

.334 |

25.6 |

23.5 |

102 |

100 |

| Young, Michael |

.300/.346/.441 |

.342 |

24.4 |

26.9 |

104 |

104 |

wOBA: Weighted on-base average as calculated by FanGraphs. Weighs singles, extra-base hits, walks, and hits by pitch; generally, .400 is excellent and .320 is league-average.

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

OPS+: Career on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 OPS+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

wRC+: Career weighted Runs Created, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 wRC+ indicating a league-average player, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a player is than a league-average player.

Here are the five pitchers, ranked by bWAR. Pitchers under discussion in this article are in bold.

| Pitchers, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Pitcher |

W-L (S), ERA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

ERA+ |

ERA–- |

FIP–- |

| Pettitte, Andy |

256-153, 3.85 |

60.9 |

68.5 |

117 |

86 |

84 |

| Moyer, Jamie |

269-209, 4.25 |

50.2 |

48.0 |

103 |

97 |

103 |

| Oswalt, Roy |

163-102, 3.36 |

50.2 |

49.8 |

127 |

79 |

78 |

| Hoffman, Trevor |

61-75 (601), 2.87 |

28.0 |

23.0 |

141 |

71 |

75 |

| Wagner, Billy |

47-40 (422), 2.31 |

27.7 |

23.6 |

187 |

54 |

63 |

bWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference.

fWAR: Career Wins Above Replacement as calculated by FanGraphs.

ERA+: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA+ indicating a league-average pitcher, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

ERA–: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA– indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

FIP–: Fielding-independent pitching, a pitcher's ERA with his fielders' impact factored out, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 FIP– indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

The table below combines both position players and pitchers into a ranking by bWAR with their fWAR values also listed. Players under discussion in this article are in bold.

| All Players, Ranked by bWAR |

|||

| Rank |

Player |

bWAR |

fWAR |

| 1 |

Rolen, Scott |

70.0 |

69.9 |

| 2 |

Jones, Andruw |

62.8 |

67.6 |

| 3 |

Helton, Todd |

61.5 |

55.3 |

| 4 |

Pettitte, Andy |

60.9 |

68.5 |

| 5 |

Edmonds, Jim |

60.3 |

64.0 |

| 6 |

Sheffield, Gary |

60.2 |

62.4 |

| 7 |

Guerrero, Vladimir |

59.3 |

56.5 |

| 8 |

Damon, Johnny |

56.0 |

42.9 |

| 9 |

Berkman, Lance |

51.8 |

55.5 |

| 10 |

Moyer, Jamie |

50.2 |

48.0 |

| 11 |

Oswalt, Roy |

50.2 |

49.8 |

| 12 |

Vizquel, Omar |

45.3 |

42.0 |

| 13 |

Delgado, Carlos |

44.3 |

43.5 |

| 14 |

Garciaparra, Nomar |

44.2 |

41.5 |

| 15 |

Posada, Jorge |

42.7 |

44.9 |

| 16 |

Ordonez, Magglio |

38.5 |

37.8 |

| 17 |

Renteria, Edgar |

32.1 |

35.5 |

| 18 |

Anderson, Garret |

25.6 |

23.5 |

| 19 |

Young, Michael |

24.4 |

26.9 |

| 20 |

Hoffman, Trevor |

28.0 |

23.0 |

| 21 |

Wagner, Billy |

27.7 |

23.6 |

As with previous assessments that use WAR as a ranking tool, WAR is not the be-all-and-end-all statistic although it is a fair assessment of player value: It measures a player's contribution to his team's wins, and it is the only qualitative statistic that enables comparison between position players and pitchers.

As a rough rule of thumb, position players and starting pitchers with a bWAR of 60 or more typically garner serious consideration for the Hall while relief pitchers generate the same consideration at 40 or more. Players with a bWAR of 50 or more do tend to sit on the bubble, with many other factors deciding whether they are legitimate Hall of Famers. That rough rule of thumb is in force in the individual assessments below—although there may be a surprise or two—as we examine the 11 borderline Hall of Fame candidates expected to appear on ballots in the next three years. Let's start with the three "bubble" candidates for the 2015 ballot.

2015: Carlos Delgado, Nomar Garciaparra, Gary Sheffield

With three superstar pitchers slated for the 2015 ballot—Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, and John Smoltz—anyone else on the ballot is sure to be overshadowed, and we will see if these three candidates will be unfairly overlooked.A fixture on the Toronto Blue Jays for 12 of his 17 Major League seasons, a club for which he established several batting records, Carlos Delgado was an excellent power hitter—but his misfortune is being a power hitter at a position, first base, that is amply represented in the Hall of Fame by power hitters. For Delgado to make it into the Hall, he would have needed to be a dominant power hitter—and as Delgado was a typically deficient defensive first baseman who stole fewer than one base per season, his legacy rests on his hitting.

Delgado is one of only six players in baseball history to hit 30 or more home runs in 10 consecutive seasons, and for 13 seasons, from 1996 to 2008, he hit at least 25 home runs in all but one of those seasons, falling one shy of that in 2007, his age-35 season. His prime coincided with the Steroids Era, but Delgado has never been associated with PEDs, and his home run totals reflect those of a "clean" hitter, with the 44 round-trippers he hit in 1999 representing his single-season best. During that stretch, Delgado posted a .282/.386/.552 slash line, essentially equivalent to his career .280/.383/.546 line, while averaging 36 doubles, 35 home runs, 92 runs scored, and 112 runs batted in every year. His seasonal average OPS+ of 140 practically matches his career OPS+ of 138.

The consistent first baseman finished within the top five for Most Valuable Player voting twice. In 2000, he finished fourth and led the American League in doubles with 57 and total bases with 378 while slugging 41 long flies, driving in 137 runs, and posting an outstanding .344/.470/.664 slash line—his OPS+ of 181 was the best of his career. In 2003, he was the runner-up MVP to Alex Rodriguez with a record that in several categories was virtually indistinguishable from the Texas Rangers' shortstop; Delgado led the AL in RBI (145), OPS (1.019), and OPS+ (161) while batting at a .302/.426/.593 clip with 42 homers. The 2003 season also saw Delgado hit four home runs in a single game against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, and he is the only player of the 16 all-time to accomplish this feat to hit his four dingers in only four at-bats.

With his 473 career home runs and 1512 career RBI, Delgado looks a lot like Fred McGriff, another left-handed slugging first baseman who got his start in Toronto. But McGriff, who has yet to reach 25 percent of the vote on any of the five ballots on which he has appeared since 2010, finished with a 52.4 bWAR, nearly 8 wins better than Delgado's 44.3. Jay Jaffe's JAWS ranking places Delgado 35th all-time among first basemen—McGriff places 27th—while both fall significantly short of the average bWAR of 65.9 for the 19 first basemen already in the Hall. Carlos Delgado was an excellent offensive first basemen, but without clear dominance during his heyday or gaudy counting numbers, Delgado is just another excellent power hitter a long way from Cooperstown.

Career-wise, first baseman Carlos Delgado looks a lot like Fred McGriff, who is being overlooked on the Hall of Fame ballot.

A textbook example of how fate can derail a baseball career at any time while illustrating how hard it is to get into the Baseball Hall of Fame, shortstop Nomar Garciaparra looked to be a superstar and a probable Hall of Famer right from his winning American League Rookie of the Year honors with the Boston Red Sox in 1997 when he led the league in hits (209) and triples (11), garnishing that with a .306/.342/.534 slash line, 30 home runs (the most ever hit by a rookie shortstop), and 98 runs batted in. After all, Garciaparra, famously fidgety while at the plate, followed that up with a 1998 campaign that included a .323/.362/.584 line with 35 homers and 122 RBI, good enough to be runner-up to the Texas Rangers' Juan Gonzalez in MVP voting, while in 1999 and 2000 Garciaparra became the first right-handed batter since Joe DiMaggio to lead the league in batting in two consecutive years.

Garciaparra batted .357 in 1999 and .372 in 2000, and having finished in the top 10 in MVP voting from 1997 to 2000, he seemed set for an auspicious career, a solid defensive shortstop and a potent offensive one, and a budding folk hero in a New England that knew him affectionately as "NO-mah!" His 1999 season included a .418 on-base percentage and a .603 slugging percentage to go with that league-leading .357 batting average, adding 42 doubles, 27 home runs, 103 runs scored, and 104 RBI while his OPS+ was 153. He posted his career-best OPS+ of 156 the following year, which saw him with a .372/.434/.599 slash line, 51 doubles, 21 home runs, 104 runs scored, and 96 RBI while leading the league in intentional walks (20).

Then Garciaparra broke his wrist early in the 2001 season; he played in only 21 games that year. He seemed to rebound the following year with a .310/.352/.528 line, collecting 197 hits in 635 at-bats, his most since 1997, including a league-leading and career-high 56 doubles along with 24 home runs, 101 runs scored, and 120 runs batted in. He posted similar numbers in 2003, but he saw limited action with Boston in 2004, not helped by trade machinations that soured Garciaparra's attitude toward the Red Sox. He was traded to the Chicago Cubs after the 2004 All-Star break, and in 2005 a groin injury sidelined him for half the season. Signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2006, for whom he made a successful transition to first base, Garciaparra continued to battle injuries even though he made his sixth and final All-Star Game in 2006, also the last season in which he hit .300 with a .303 average in 469 at-bats. But 2007 found him falling below minimum standards—his 80 OPS+, well below league-average, was the lowest of his career—and following two part-time seasons, he limped to retirement following the 2009 season that he'd spent with the Oakland Athletics.

Famously fidgety shortstop Nomar Garciaparra had a brilliant start to his career, at least with the Boston Red Sox.

Nomar Garciaparra shot out of the gate as one of the "super-shortstops," manning one of the toughest defensive positions while also posting offensive numbers like a marquee hitter. But injuries and the cavalier attitude shown by the Boston Red Sox at the end of his tenure there marred the remainder of his career. Garciaparra did retire with a .313/.361/.521 slash line, good for a 124 OPS+, a 124 wRC+, and a .376 wOBA, but his 44.2 bWAR (41.5 by FanGraphs' calculation of WAR) falls conspicuously short of Hall of Fame excellence. Jaffe's JAWS puts Garciaparra in 23rd place among shortstops, ahead of Hall of Famers such as Joe Tinker, Travis Jackson, Phil Rizzuto, and Rabbit Maranville, although whether those are legitimate Hall of Fame shortstops is another story. Had Garciaparra posted a few more superlative seasons, he could have been a dark-horse contender for the Hall. But his actual record simply underlines what might have been.

Had Gary Sheffield's name not appeared in the Mitchell Report, examination of his bona fides for the Hall of Fame would be less problematic. As it stands, Sheffield is truly on the bubble, having compiled an impressive if not dominating batting record over the course of his 22-year career, toiling for eight different teams, that saw a number of other controversies besides the PEDs issue cloud his on-field performance.

Sheffield played the corner outfield positions, primarily right field, and had come up as a third baseman with the Milwaukee Brewers, but apart from a strong throwing arm he has always been a defensive liability; his defensive WAR (Baseball Reference version) for his career is –28.6. He did steal 253 bases, at a 70.9 percent success rate, including three years with 20 or more swipes—with one of those being 22, while being caught just five times, as a Detroit Tiger during the 2007 season, his age-38 year—so Sheffield is a bit more than a one- or even two-dimensional player, but his Hall of Fame case does rest on his hitting.

In that respect, Sheffield had been a fearsome—if not dominant—hitter during his prime. He finished with a .292/.393/.514 slash line, representing 2689 hits (66th all-time), 467 doubles (89th all-time), 509 home runs (25th all-time), 1636 runs scored (38th all-time), and 1676 runs batted in (26th all-time), while his 1475 bases on balls (20th all-time) is balanced against only 1171 strikeouts (175th all-time), a remarkable feat in the free-swinging, no-shame-to-fan modern era, and one that belied the distinctive bat-wiggle in Sheffield's swing—he always looked as if he couldn't wait to come out of his shoes as he stood poised at the plate—that actually indicated impressive plate discipline.

In his first year in the National League with the San Diego Padres in 1992, Sheffield led the league in batting with a .330 average, the only Padre aside from Tony Gwynn ever to lead the league in that category. Sheffield also flirted with the Triple Crown that season as he slugged 33 homers, one behind Barry Bonds and two behind league-leader Fred McGriff, while his even 100 RBI was fifth-best in 1992, just nine behind eventual leader Darren Daulton. Sheffield also led the NL in total bases that year with 323 as he finished third in Most Valuable Player voting, the first of three top-five finishes in MVP voting, and he was selected to his first of nine All-Star berths.

For a 16-year period, from 1992 to 2007, Sheffield posted a .301/.408/.543 line generated from a seasonal average of 140 hits including 24 doubles and 29 home runs, 252 total bases, and 80 walks against only 59 strikeouts; he averaged, per season, 88 runs scored and 90 runs driven in. Sheffield's OPS+ during this period was 150; his career OPS+ is 140, 74th all-time and tied with Hall of Famers Jesse Burkett and Duke Snider. Sheffield was part of the 1997 Florida Marlins team that won the World Series, and it was with Florida, for whom he played six seasons, his longest tenure in his career, that he led the National League in on-base percentage (.465), OPS (1.090), and OPS+ (189) in 1996; he walked 142 times, 19 of those intentional, against only 66 strikeouts as he finished ninth in MVP voting and made the All-Star team.

After a four-year stint with the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1998 to 2001, Sheffield was traded to the Atlanta Braves, with whom he played two seasons before signing as a free agent with the New York Yankees in 2004. This four-year period, from his age-33 to age-36 seasons, saw him post a .304/.399/.542 line while averaging, per year, 169 hits including 30 doubles and 34 homers, 107 runs scored and 115 RBI. He was off to a similarly strong start in 2006, but a wrist injury sustained in an in-game collision sidelined him for much of the season. Sheffield made three All-Star squads during this time, and he finished in the top ten in MVP voting in three of those seasons; he was runner-up to Vladimir Guerrero in 2004.

In a phase of a ballplayer's career when he should be slowing down, Gary Sheffield displayed a resurgence that suggested performance-enhancing drugs. Sheffield was implicated in the Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative (BALCO) scandal that has dogged Barry Bonds, and it was during a 2001 workout with Bonds that Sheffield's trainer applied "the cream," a topical application reputedly containing steroids, to ripped stitches that had resulted from surgery on Sheffield's knee in an attempt to heal the ripped stitches. Sheffield was later named in the Mitchell Report as having received PEDs from BALCO. There is little doubt that the PEDs issue will color the evaluation of Gary Sheffield's qualifications for the Baseball Hall of Fame. Sheffield's hot temper and his accusations of racism and poor management over the years will likely receive play as well.

Will slugger Gary Sheffield's association with PEDs sully his Hall of Fame chances?

As a ballplayer, Sheffield compiled an excellent career, although it lacks the standout, dominant moment often associated with a Hall of Fame-caliber player. Sheffield's bWAR of 60.2 and fWAR of 62.4 merits his serious consideration for the Hall, but without a distinguishing characteristic it is hard to consider him a Hall of Famer. He did reach the 500-homer plateau, but over a 22-year career that smacks more of a compiler than a superstar. Jay Jaffe's JAWS ranks him 23rd among right fielders, ahead of Hall of Famers Willie Keeler, Enos Slaughter, and Sam Rice, among others, but behind Hall of Famers Paul Waner, Sam Crawford, Tony Gwynn, and Dave Winfield, as well as sabermetric darlings Dwight Evans and Reggie Smith, both hoping for a future Expansion Era Committee nod.

That may be Gary Sheffield's best hope as well, as his PEDs notoriety, the overstuffed ballot, and his own lack of a clear-cut Hall of Fame case will find him languishing on the 2015 ballot and beyond.

2016: Garret Anderson, Jim Edmonds, Trevor Hoffman, Billy Wagner

While the marquee player on the 2016 ballot will be Ken Griffey, Jr., with discussion likely to include speculation of how much more he could have accomplished had he not missed so much playing time because of injuries, the next player in line will be Trevor Hoffman. The durable relief pitcher, the first to reach 600 saves, was perhaps even more impressive because as a closer, he did not have an overpowering fastball but instead relied on his changeup. But despite Hoffman's auspicious career numbers, his case for the Hall of Fame may not be so apparent.Meanwhile, three first-time candidates on the 2016 ballot could find themselves lost in the shuffle, and in the case of two of them, that may be a shame as their careers are more substantial than they may first appear. The third, on the other hand, may be a case study in how a superficial look at a career does not tell the whole story.

As the long-time left fielder for the Angels, Garret Anderson can truly be considered a "franchise player" as he spent all but two seasons of his 17-year career with the team. (And let's get the team-name merry-go-'round out of the way now: When Anderson joined the team in 1994, the club was called the California Angels. From 1997 to 2004, they were the Anaheim Angels. But starting in 2005, thanks to owner Arte Moreno's craven marketing sycophancy, they have been known as the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, the silliest name in baseball.) Yet despite being a "franchise player," Anderson was more like a fixture than a star.

I'm a long-time resident of Orange County, California, and although I'm not actually an Angels fan (as a lifelong San Francisco Giants fan, any stirrings of fandom I may have been feeling for the Angels were dashed in 2002), I've attended many Angels games because they are the local venue for Major League Baseball. In that time, Anderson was always the second banana, whether to Tim Salmon, Jim Edmonds, Vladimir Guerrero, or even Mo Vaughn during his much-ballyhooed yet ultimately undistinguished two-year stint with the club.

And despite persistent remarks about Anderson "dogging it" that swirled around Angel Stadium and in the local media, he was a consistent ballplayer, one who was the runner-up for the American League Rookie of the Year in 1995, when he posted a .321/.352/.505 slash line with 120 hits in 374 at-bats including 19 doubles and 16 home runs, 50 runs scored, and 69 runs driven in. (He placed second to the Minnesota Twins' Marty Cordova, and I had to refresh my memory too.)

For his career, Anderson produced a .293/.324/.461 line as in 2228 games, yielding 9177 plate appearances and 8640 at-bats, he collected 2529 hits (92nd all-time) including 522 doubles (44th all-time) and 287 homers (152nd all-time), scored 1084 runs (256th all-time), and drove in 1365 runs (84th all-time, and tied with Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda). Anderson led the AL in doubles in two consecutive years, hitting 56 in 2002 and 49 in 2003, as he smacked 30 or more two-baggers in ten seasons, eight of those consecutively from 1996 to 2003.

But a "consistent" ballplayer is not the same as a Hall of Fame ballplayer, and Garret Anderson's career is that of a compiler. He was good enough to keep a starting slot in the lineup by avoiding injury and maintaining production: For 14 consecutive seasons, from 1996 to 2009, Anderson averaged for each season 146 games played, 614 plate appearances and 578 at-bats that produced 170 hits, including 36 doubles and 19 homers, and 268 total bases, in turn generating a .293/.325/.463 slash line while he scored 73 runs and drove in 92. He finished fourth in AL MVP voting in 2002, when he batted .306 with 29 round-trippers and a league-leading 56 doubles.

Left fielder Garret Anderson was an Angels' lineup fixture--but does that make him a Hall of Famer?

Yet the value of Anderson's production tells a different story. His career OPS+ of 102 and career wRC+ of 100 indicate a league-average player—not an insult, but neither a superlative. Anderson generated a 25.6 bWAR and a 23.5 fWAR, hardly Hall of Fame-caliber. Indeed, Jaffe's JAWS places Anderson at 85th place among all left fielders, well below even marginal, if not openly disputed, Hall of Famers Chick Hafey and Jim Rice. Garret Anderson was solid and reliable, but despite his racking up a few fairly impressive numbers, he was not a Hall of Fame-level player.

On the other hand, the same cannot be said for Jim Edmonds, although like Garret Anderson and Gary Sheffield, it is difficult to see how Edmonds's offensive production stood out from the competition. Defensively, of course, Edmonds may be a whole other story, although in the video age his spectacular highlight-reel footage may overshadow his overall defensive metrics as a center fielder. Edmonds did win eight Gold Gloves as an outfielder, and only seven other outfielders have won more since the award was instituted in 1957, while his defensive WAR of 5.9 is certainly respectable for a defender at one of the strength positions up the middle.

A defensive wizard in center field, does Jim Edmonds have the overall career brilliance for the Hall of Fame?

Defensive metrics are still a work in progress—although they are still a better indicator of defensive effectiveness than simply using fielding percentage—but they are generally favorable to Edmonds. FanGraphs' Total Zone rating gives Edmonds a 90 for his career; Total Zone is a runs-scored index, with a zero indicating a league-average defender, so Edmonds was 90 runs-saved better than a league-average defender.

For comparative purposes, these are the FanGraphs' Total Zone ratings for center fielders currently enshrined in the Hall of Fame:

| Player |

Total Zone Rating |

| Mays, Willie |

191 |

| Speaker, Tris |

91 |

| Carey, Max |

86 |

| Ashburn, Ritchie |

77 |

| Dawson, Andre |

69 |

| Duffy, Hugh |

68 |

| DiMaggio, Joe |

49 |

| Hamilton, Billy |

30 |

| Doby, Larry |

21 |

| Combs, Earle |

6 |

| Cobb, Ty |

0 |

| Roush, Edd |

–6 |

| Puckett, Kirby |

–15 |

| Snider, Duke |

–21 |

| Mantle, Mickey |

–28 |

| Averill, Earl |

–32 |

| Wilson, Hack |

–32 |

Should Edmonds be elected to the Hall, his Total Zone index of 90 would place him third all-time—and what center fielder would mind ranking behind Willie Mays and Tris Speaker? For further comparison, Kenny Lofton, who fell off the ballot after his first appearance last year, has a 113 Total Zone Rating. Ken Griffey, Jr., who will be on the same ballot as Edmonds, has a TZ rating of –17, while Andruw Jones, expected to be on the 2018 ballot, nets a TZ rating of 242. Elsewhere, the Baseball Reference version of Total Zone Rating lists Edmonds at 85 runs saved while the site's Defensive Runs Saved index puts him at –7.

But while Edmonds may in fact be one of the defensive greats in center field—you can believe the highlight-reel footage—how does he stack up as a hitter? Will his bat help to carry him into Cooperstown?

Qualitatively, Edmonds looks strong if not overpowering, with a slash line of .284/.376/.527 producing an OPS of .903 and an OPS+ of 132 (tied with Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn, Joe Morgan, and Jackie Robinson), with a wRC+ of 132 and a wOBA of .385. In 2011 games, with 7980 plate appearances and 6858 at-bats, Edmonds generated a bWAR of 60.2 and an fWAR of 64.0. Jaffe's JAWS ranking puts Edmonds in 14th place among all center fielders; his top-seven bWAR years total 42.5, 1.6 wins behind the average of 44.1 based on the 18 center fielders already in the Hall of Fame, while his JAWS of 51.4 is 5.8 wins behind the aggregate average of 57.2, and his overall bWAR of 60.2 is 10.2 wins behind the 70.4 aggregate average.

Quantitatively, Edmonds, who had been dogged by injuries during his career, compiled decent if not spectacular numbers. He fell just short of 2000 hits; his 1949 hits are 299th all-time. His 437 doubles are 126th all-time, just behind Hall of Famers Luke Appling, Roberto Clemente, and Eddie Collins. His 393 homers ranks 56th all-time, just behind Hall of Famers Duke Snider and Al Kaline. In runs scored, Edmonds ranks 146th all-time with 1251, and in runs batted in, he places 152nd among career leaders with 1199, just behind Hall of Famer Chuck Klein.

Edmonds never led the league in any offensive category. He finished within the top five in Most Valuable Player voting twice: In 2000, his first year with the St. Louis Cardinals, he placed fourth, compiling a .295/.411/.583 line, 42 home runs (tied for seventh-best in the National League), 129 runs scored (tied for third-best), and 103 walks (tied for fourth-best). Edmonds also generated 167 strikeouts that year, third-best in the NL; always a free swinger, Edmonds finished with 1729 career whiffs, 25th all-time, ahead of Hall of Famers Mickey Mantle and Harmon Killebrew and just behind Hall of Famer Lou Brock—although this is hardly an auspicious career highlight.

In 2004, Edmonds placed fifth in NL MVP voting although he had a better year than he had in 2000: He posted a .301/.418/.643 slash line—his .418 on-base percentage was sixth-best in the NL while his .643 slugging average placed third—from 150 hits, 38 doubles, 42 home runs (tied for fifth-best), 320 total bases (sixth-best), and 101 walks (ninth-best), yielding career bests in OPS (1.061, fourth-best in the NL that season) and OPS+ (171, third-best), while producing 102 runs scored and 111 runs batted in (sixth-best).

Unlike his California/Anaheim Angels teammate Garret Anderson, Jim Edmonds, when I saw him in the late 1990s, felt like a game-changing player, whether in center field or at the plate. (I still remember his walk-up music—Limp Bizkit's "Nookie.") He could make a spectacular catch or deliver a clutch hit. And with his career bWAR of 60.3—with FanGraphs giving him a more bullish 64.0—Edmonds deserves serious consideration for the Hall of Fame. Jay Jaffe's JAWS places Edmonds 14th all-time among center fielders, just behind Hall of Fame members Ritchie Ashburn, Andre Dawson, and Billy Hamilton and well ahead of several Hall of Famers including Larry Doby, Kirby Puckett, Max Carey, Earl Averill, and others.

Despite the highlight-reel catches, however, Jim Edmonds does not feel like a Hall of Fame player. He feels like one who is very close, particularly as a defensive centerfielder—he ranks 17th all-time in double plays turned by a center fielder (31), and 20th all-time in putouts (4343) and assists (116). But while Edmonds was a key ingredient on the Angels and the Cardinals, with whom he went to the World Series twice, winning it in 2006—although Edmonds was not an offensive factor in either Series—he was not the prime ingredient, one who shone like a Hall of Famer does. A truly stand-out season or an auspicious career offensive milestone would have bolstered Jim Edmonds's case for the Hall, but as it stands, there are a couple of other borderline center fielders with stronger credentials than his.

As the first relief pitcher to record both 500 saves and 600 saves, becoming one of only two men ever to accomplish those feats, Trevor Hoffman is in some rarefied company—only Mariano Rivera has ever reached those milestones, with Rivera finishing as the all-time leader in saves with 652; Hoffman had notched 601 before retiring. Thus, it is hardly surprising that Major League Baseball has, as of 2014, not only created an award given to the top relief pitcher in each league—up until now, an award had been given to the top reliever in both leagues—but has named the award for each league in honor of Hoffman, for the National League, and in honor of Rivera, for the American League. Hoffman spent his entire career in the NL, most of that with the San Diego Padres, while Rivera spent his entire career with the AL New York Yankees.

Will it be "Trevor Time" in Cooperstown for Trevor Hoffman, the first relief pitcher to reach 600 career saves?

Perhaps the awarding of the top reliever in each league, instead of both combined, is an acknowledgement of the fundamental change in relief pitching in baseball: Historically, the starting pitcher was expected to finish the game, with a relief pitcher coming in only if the starter got into trouble. Now pitching philosophy is structured on the premise that the starting pitcher will pitch into the later innings, such as the sixth, at which point a series of relief pitchers take over, culminating with the closer, whose function is to secure the final three outs of the game, at which point the closer has "saved" the game.

We are simplifying somewhat as there are specific criteria for earning a save, and we will not delve into whether the save is an overrated statistic that does not measure how effective a relief pitcher, specifically the closer, is. And we will touch only briefly on this: In previous decades, a relief ace would enter the game not just at the optimum time currently, which is at the start of the ninth inning with the bases empty. Instead, the relief ace was often called the "fireman" because he entered at any time when the game was "heating up"—the other team was threatening to tie or surpass the reliever's team, and it was his job to "put out the fire" and ensure that the other team was denied. Some analysts criticize the current use of the closer, arguing that if the closer is the best relief pitcher on a staff, he should be brought in to pitch precisely in those "high-leverage" situations—putting out the fire as in earlier eras—when the fate of the game is on the line, and not exclusively for the final three outs, which may not be the most critical outs, but for which the closer will get credit for "saving" the game.

In any event, the Baseball Hall of Fame has never been receptive to honoring role players such as a relief pitcher. To date, only five relievers have been enshrined in the Hall: Dennis Eckersley, Rollie Fingers, Rich "Goose" Gossage, Bruce Sutter, and Hoyt Wilhelm, and Eckersley spent the first half of his career as a starting pitcher before switching roles. The other four epitomized the era of the "firemen," especially Wilhelm, who in many respects pioneered the closing role. The case of Lee Smith is emblematic of the Hall's indifference to relief pitchers: Smith is the prototype of the modern closer, the one-inning specialist who enters the game to record the final three outs. Smith retired after the 1997 season with 478 saves, the most all-time until passed by Hoffman and then Rivera. He has been on the Hall of Fame ballot for 12 years, but he has yet to reach 50 percent of the vote, let alone the 75 percent needed for induction. In his most recent appearance on the ballot in 2014, he lost nearly 18 percent of the votes from the previous year's showing and fell to a tick beneath 30 percent—hardly an encouraging sign as he has just three more chances for election by the BBWAA. (Lee is grandfathered to complete his 15 total years' eligibility that was in force when he first qualified for the ballot, provided he maintains at least five percent of the vote in the next two years.)

Adding to Smith's woes will be the appearance of Hoffman on the 2016 ballot, who had surpassed him as the all-time saves leader until Hoffman himself was surpassed by Rivera. But as the number of saves itself is not an accurate indicator of relief-pitching effectiveness, and thus a criterion for Hall of Fame inclusion, let's examine these closers a little more closely.

The following two tables list various criteria of relief-pitching effectiveness, the first concentrating on the save situation itself, and the second on the effectiveness of the pitching in those situations, with each criterion explained below its respective table. The sample includes the five Hall of Fame relievers already mentioned along with Hoffman, Rivera, Smith, and Billy Wagner, who is eligible for the Hall in 2015.

This table ranks the relief pitchers by save percentage and lists career statistics for end-of-game performance and the leverage—the "pressure"—faced in those situations. (Note: Dennis Eckersley's statistics are for his relief pitching only.)

| Relief Pitchers, Ranked by Save Percentage |

||||||

| Pitcher |

GF |

SV OPP |

Saves |

Blown Saves |

SV PCT |

aLI |

| Rivera, Mariano |

952 |

732 |

652 |

80 |

.891 |

1.868 |

| Hoffman, Trevor |

856 |

677 |

601 |

76 |

.888 |

1.914 |

| Wagner, Billy |

703 |

491 |

422 |

69 |

.859 |

1.812 |

| Eckersley, Dennis |

577 |

461 |

390 |

71 |

.846 |

1.398 |

| Smith, Lee |

802 |

581 |

478 |

103 |

.823 |

1.865 |

| Wilhelm, Hoyt |

651 |

295 |

227 |

72 |

.769 |

1.348 |

| Fingers, Rollie |

709 |

450 |

341 |

109 |

.758 |

1.604 |

| Sutter, Bruce |

512 |

401 |

300 |

101 |

.748 |

1.969 |

| Gossage, Goose |

681 |

422 |

310 |

112 |

.735 |

1.584 |

SV OPP: Save Opportunities, the number of times the pitcher entered the game qualified to earn a save. Typically the sum of saves and blown saves, but rules in place prior to 1973 results in an anomaly for Hoyt Wilhelm, whose career dated back to 1952.

Saves: Credit to a pitcher for successfully maintaining his team's lead in a game, as defined by Rule 10.19 of the Official Rules of Major League Baseball.

Blown Saves: Credited to a pitcher who entered a game with a save opportunity but failed to maintain the lead, allowing the other team to tie or surpass his team's lead.

SV PCT: Save Percentage, the ratio of saves to save opportunities.

aLI: Average Leverage Index, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Measures the amount of "pressure" the pitcher experienced in his appearances. Average pressure is 1.0, low pressure is below 1.0, and high pressure is above 1.0.

This table ranks the relief pitchers by ERA+ and lists various measurements of the pitchers' performance in limiting opposing teams' offensive effectiveness. (Note: Dennis Eckersley's statistics are for his relief pitching only, with an asterisk (*) indicating an aggregate statistic as the reliever-only statistic is not available.)

| Pitchers, Ranked by ERA+ |

|||||||

| Pitcher |

Slash Line |

ERA+ |

ERA– |

FIP–- |

WHIP |

SO/9 |

SO/BB |

| Rivera, Mariano |

.211/.262/.293 |

205 |

49 |

63 |

1.000 |

8.2 |

4.10 |

| Wagner, Billy |

.187/.262/.296 |

187 |

54 |

63 |

0.998 |

11.9 |

3.99 |

| Wilhelm, Hoyt |

.216/.288/.308 |

147 |

68 |

81 |

1.125 |

6.4 |

2.07 |

| Hoffman, Trevor |

.211/.267/.342 |

141 |

71 |

75 |

1.058 |

9.4 |

3.69 |

| Sutter, Bruce |

.230/.288/.340 |

136 |

75 |

78 |

1.140 |

7.4 |

2.79 |

| Smith, Lee |

.236/.306/.341 |

132 |

76 |

74 |

1.256 |

8.7 |

2.57 |

| Gossage, Goose |

.228/.308/.330 |

126 |

80 |

84 |

1.232 |

7.5 |

2.05 |

| Fingers, Rollie |

.235/.292/.340 |

120 |

83 |

83 |

1.156 |

6.9 |

2.64 |

| Eckersley, Dennis |

.225/.259/.352 |

116* |

86* |

84* |

0.998 |

8.8 |

6.29 |

ERA+: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by Baseball Reference. Positively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA+ indicating a league-average pitcher, and values above 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

ERA–: Career ERA, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 ERA– indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

FIP–: Fielding-independent pitching, a pitcher's ERA with his fielders' impact factored out, league- and park-adjusted, as calculated by FanGraphs. Negatively indexed to 100, with a 100 FIP– indicating a league-average pitcher, and values below 100 indicating the degrees better a pitcher is than a league-average pitcher.

WHIP: Walks and Hits per Innings Pitched.

SO/9: Strikeouts per nine innings pitched, the number of strikeouts by a pitcher, multiplied by 9, then divided by the number of innings the pitcher pitched, to project the average number of strikeouts a pitcher would record over the course of an entire game.

SO/BB: The ratio of a pitcher's strikeouts to bases on balls (or walks).

With respect to save conversions, Trevor Hoffman ranks behind only Mariano Rivera in terms of effectiveness, although as modern-day closers they typically entered a game at the start of the ninth inning, with no runners on base, whereas relievers from earlier eras—Wilhelm, Fingers, Gossage, Sutter—came on in an earlier inning with runners already on base. It is instructive, though, that Hoffman is second in average leverage index, or pitching in high-pressure situations.

In terms of overall pitching effectiveness, Hoffman is equal to or better than the relievers already in the Hall of Fame, and he even bests Rivera in strikeouts per nine innings. That is significant because Hoffman, initially a power pitcher, hurt his pitching shoulder in an off-season injury in 1994 that later necessitated rotator-cuff surgery, which diminished the velocity of his fastball. As a result, he developed a devastating changeup as his out pitch, setting it up with his other pitches, although, like Rivera and his cut fastball, Hoffman too had a pitch that every batter knew was coming, yet those batters had difficulty with it all the same.

In the highly volatile role of closer, one which sees high turnover and variable degrees of effectiveness by the pitcher from season to season, Hoffman was remarkably consistent and remarkably effective. For a 14-year period, from 1994 to 2007, Hoffman averaged, per season, 58 appearances and 61 innings pitched, allowing just 46 hits including 5 home runs while striking out 66 and walking only 16, earning 37 saves while posting a 2.61 ERA, a 154 ERA+, a 1.020 WHIP, a 9.8 strikeouts-per-nine-innings ratio, and a 4.12 strikeouts-to-walks ratio.

What is even more impressive is that Hoffman accomplished this while pitching for the San Diego Padres, which had reached the postseason during his time with them just four times, advancing beyond the first round only once. That was in 1998, when the Padres made the World Series but were swept by the New York Yankees—Mariano Rivera's Yankees—with Hoffman, in his only World Series appearance, blowing his only save opportunity in Game Three. In 2007, the Padres battled the Colorado Rockies for the National League wild-card slot, forcing a Game 163 of the regular season in Denver, an exciting contest that went 13 innings. Entering the bottom of the 13th with an 8–6 lead, the Padres brought in Hoffman to save that lead, but he surrendered three runs—the winning one a controversial play at the plate—and was tagged with the loss.

That is the fundamental difference between Hoffman and Rivera—unlike Hoffman, Rivera has been no stranger to the postseason limelight, and he is the greatest postseason relief pitcher ever, but that is as much a function of his team getting him to the postseason in the first place as his performance while there. And Rivera has some high-profile playoff meltdowns too, such as Game Four of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the Boston Red Sox, certain to be eliminated in four games in the bottom of the ninth inning when, facing Rivera, the Red Sox scored a run to force extra innings before winning in the bottom of the twelfth inning; they went on to win the series, the only MLB team to win a seven-game series after losing the first three games of that series. Rivera's blown save in Game Seven of the 2001 World Series against the Arizona Diamondbacks was an even bigger meltdown in one of the most exciting Series in history: Tacked to a one-run lead entering the eighth inning, Rivera struck out the side—he did allow a two-out single—before facing the D-Backs again in the ninth, in which he gave up two runs, one resulting from his own error, as Arizona came from behind to win its first (and to date only) World Series.

But when compared to both his contemporaries and those relievers already in the Hall, Trevor Hoffman ranks among the best at the position based on both his qualitative and quantitative record. Jaffe's JAWS ranks Hoffman at 21st place among relievers, behind Lee Smith (although ahead of Rollie Fingers), but that is a ranking based exclusively on bWAR alone and does not tell the entire story as Hoffman's consistency and excellence at his position is among the best-ever at that position. (And JAWS also factors in Dennis Eckersley's not-inconsiderable bWAR as a starting pitcher, thus skewing the range.)

And although it is hardly a factor in the evaluation, Hoffman did help to personify the mystique of the closer. In 1998, the Padres introduced "Trevor Time," the announcement that Hoffman was entering the game, running in from the bullpen to the accompaniment of AC/DC's "Hells Bells." It was a gimmick that spread throughout baseball; even the Yankees were not immune—a year later, in honor of Rivera, nicknamed "the Sandman," they began announcing his entrance by using Metallica's "Enter Sandman." (And we'll leave it to pop-culture mavens to ponder the significance, if any, of those two bands, Metallica and AC/DC, also being the favorites of, respectively, MTV's Beavis and Butt-head.)

Although his relatively low profile may make Trevor Hoffman seem to be little more than a compiler, his quantitative and—more importantly—his qualitative record put him on a par with not only existing Hall of Fame relievers but also with certain Hall of Famer Mariano Rivera. He belongs in the Hall.

That could also be the case for Billy Wagner, who may be the best relief pitcher about whom you never gave a second thought, but whose own record prompts serious consideration for the Hall of Fame. He may be the greatest left-handed reliever of all-time, but that will not be enough to get him into the Hall. Nor will his ranking fifth in all-time saves with 422, one of only five pitchers with 400 or more saves, although as we have seen with the qualitative comparisons for relief pitchers, Wagner looked pretty formidable with a 187 ERA+, second only to Mariano Rivera in our sample, and an unreal 11.9 strikeouts per nine innings pitched, which topped all nine relievers.

Perhaps the greatest left-handed relief pitcher of all time--is that enough to get Billy Wagner into the Hall of Fame?

The two biggest knocks against Wagner are longevity and anonymity. Although Wagner's career lasted 16 years, from 1995 to 2010, and he made 853 appearances, all in relief, he totaled 903 innings pitched, which is light for Hall of Fame consideration as all the other relievers in our comparisons logged at least 1000 innings pitched. (Even John Hiller, a criminally underrated pitcher from 1965 to 1980, whose 545 appearances included just 43 starts, compiled a hefty 1242 innings pitched as one of those stalwart "firemen" riding to the rescue while earning a modest—by today's standards—125 saves.) Moreover, Wagner, who had nine seasons with 30 or more saves, appeared atop the leaderboards only twice, both for games finished, first in 2003 with 67 finishes for the Houston Astros, and then in 2005 with 70 for the Philadelphia Phillies.

Wagner did finish within the top ten in Cy Young voting twice. In 1999, he placed fourth as in 68 appearances totaling 74.2 innings he notched 39 saves in 42 opportunities, striking out 124 against only 23 walks for a 14.9 strikeouts-per-nine-innings-pitched ratio and a 5.39 strikeouts-to-walks ratio, while he compiled a miniscule WHIP of 0.777. Wagner generated an outstanding 1.57 ERA and an equally impressive 1.65 FIP—he hardly needed his fielders—and an otherworldly 287 ERA+, the first of four times he generated an ERA+ over 200 in seasons in which he pitched at least 65 innings. Wagner finished sixth in Cy Young voting in 2006, his age-34 season, amassing 70 appearances, 72.1 innings pitched, 40 saves in 45 opportunities, 94 strikeouts against 21 walks to yield an 11.7 K/9 ratio, a 4.48 K/BB ratio, and a 1.106 WHIP. Wagner's 2.24 ERA was balanced by a 2.84 FIP, but he generated a 196 ERA+.

An archetypal power pitcher with a fastball that could hit triple digits and that had good movement on it, Wagner complemented the heat with a hard slider, making him an outstanding reliever. Injuries nagged him at the end of his career, although in his final campaign, the 2010 season in his age-38 year, he delivered for the Atlanta Braves a record of 7 wins against only 2 losses with 37 saves in 71 appearances, all in relief, as in 69.1 innings pitched he posted a 1.43 ERA, a 2.10 FIP, and a 275 ERA+, striking out 104 batters while walking only 22 for a 0.865 WHIP, a 13.5 K/9 ratio, and a 4.73 K/BB ratio.

Wagner's postseason appearances were significantly less auspicious—in fact, you could say that, overall, they were a disaster. Facing 59 batters in just 11.2 innings pitched, he gave up 21 hits, 3 of those home runs, and 13 earned runs for a 10.03 ERA. The fireballing southpaw also had contentious words for his former employers the Astros, the Phillies, and the New York Mets, but neither aspect will be what keeps him out of the Hall of Fame. Despite Billy Wagner's dominating stuff, he did not dominate the leaderboards, and without the gaudy counting numbers, and until the Hall develops an approach to recognize role players—if it ever does—Billy Wagner will be lucky to stay on the ballot past his first year.

2017: Vladimir Guerrero, Magglio Ordonez, Jorge Posada, Edgar Renteria

The expected 2017 ballot does have two players who look to be clear-cut Hall of Famers: Manny Ramirez and Ivan Rodriguez. Both have been discussed previously; Ramirez is unlikely to get any recognition for his accomplishments because of his documented PEDs associations, and if the rumors of PEDs association don't dog Rodriguez, he is practically a lock for the Hall as one of the greatest catchers of all time.But joining them on the ballot in 2017 are four high-profile players who may nevertheless be overshadowed by the discussion about Ramirez and Rodriguez. Foremost among them is Vladimir Guerrero, who could give Ramirez a run for his money as the greatest right-handed hitter of his era. Guerrero was certainly among the most feared hitters in his prime, as he led the league in intentional walks five times, four of those consecutively from 2005 to 2008, and finished fifth all-time with 250 (Ramirez is 11th with 216).

For an 11-year period, from 1998 to 2008, Guerrero hit at least .300 and slugged at least 25 home runs in every season while driving in at least 100 runs in all but two of those years. During that time, Guerrero averaged, per season, 185 hits including 35 doubles and 35 homers, totaling 331 bases, while scoring 98 runs and knocking in 112, and his .325/.392/.581 slash line produced a 149 OPS+ and a 5.0 bWAR, the latter indicating an All-Star-caliber player, as indeed Vladdy was for 8 of those 11 years, adding his final All-Star appearance in 2010. He reached at least 200 hits in four different season, leading the National League in hits in 2002 with 206 while playing for the Montreal Expos; he also led the NL in total bases that year with 364, and although he—rather dubiously—led the NL in times caught stealing with 20, that is balanced against the 40 bases he did steal successfully—while ending the season with 39 round-trippers, putting him one homer shy of the exclusive 40-40 club.

In his first year in the American League, playing for the (then-)Anaheim Angels, Guerrero led the AL in runs scored (124) and total bases (366) while making a most auspicious debut in what was regarded as the tougher league. Brandishing a slash line of .337/.391/.598, Guerrero added 206 hits, tying his career high, including 39 doubles and 39 long balls while generating 126 runs batted in and an OPS+ of 157. He was named the American League Most Valuable Player, although there were other deserving candidates that year who may have had a better season than did Guerrero. Still, it was hardly as if he stole the award. Guerrero finished in the top ten of MVP voting five other times during his career.

What makes Guerrero's batting prowess even more remarkable is that he was a notorious bad-ball hitter, swinging at—and connecting with—pitches outside the strike zone. Yet Guerrero struck out only 985 times in 8155 at-bats and never reached the 100-strikeout plateau once. And even though Guerrero walked unintentionally only 487 times in 9059 plate appearances (he was intentionally walked 250 times), his career on-base percentage of .379 ranks 182nd all-time.

Quantitatively, Guerrero's all-time rankings include being 38th in home runs (449), 46th in total bases (4506), 54th in runs batted in (1496), 80th in doubles (477), 83rd in hits (2590), and 112th in runs scored (1328). Qualitatively, he is 24th all-time in slugging percentage (.553), 57th in batting average (.318; tied with Hall of Famer Arky Vaughan), 74th in OPS+ (140), and 182nd in on-base percentage (.379).

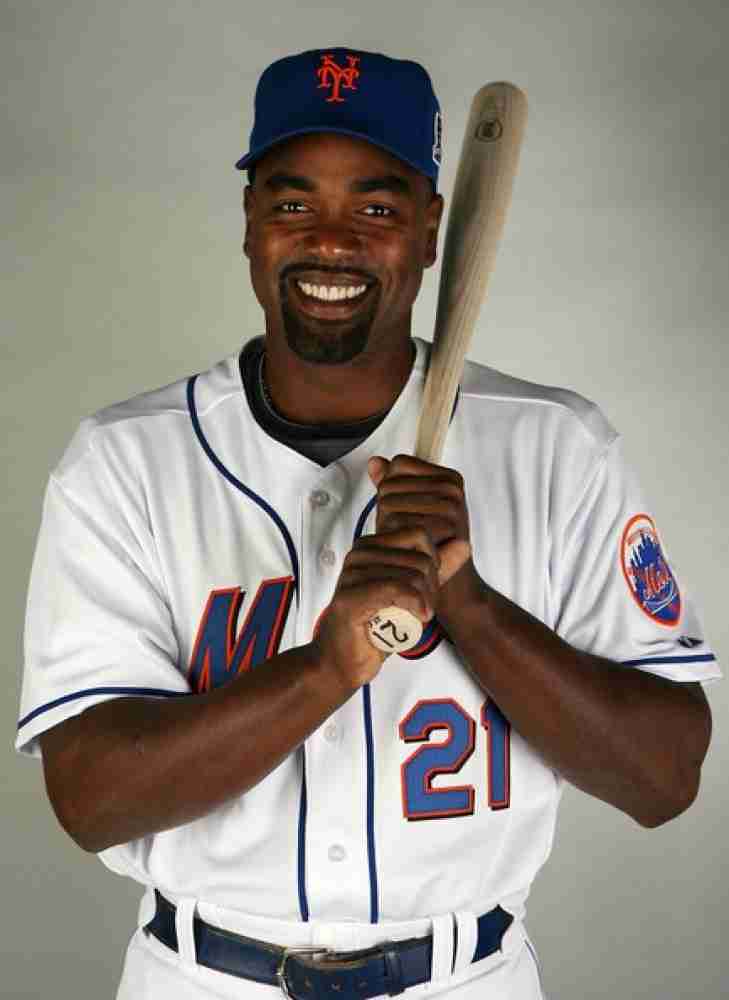

Slugging right-fielder Vladimir Guerrero's was a can't-miss at-bat. Sounds like a Hall of Famer, doesn't it?

Defensively, Guerrero had a cannon for an arm, and he is 17th all-time among right fielders in putouts with 3165 and 26th assists with 126. However, he was not as diligent as a fielder as he was as a hitter: Even though Guerrero is credited with 42 Total Zone total fielding runs above average (Baseball Reference version), his seasonal decline began in 2006, and by 2010 Guerrero was a designated hitter for the large majority of his games, with that becoming exclusive by 2011, his final season; FanGraphs lists him at 43 in Total Zone and marks his decline starting in 2008; moreover, Baseball Reference lists him at a career 26 runs below average (–26) in defensive runs saved above average while that site's defensive WAR for his career is –10.7, with –6.1 coming from his six seasons with the Angels.

The last image of Vladimir Guerrero defensively may be his fumbling around in right field at AT&T Park, committing two errors during Game One of the 2010 World Series as his Texas Rangers took on the Giants in San Francisco. Tellingly, Guerrero sat out Game Two, still in San Francisco (Nelson Cruz started in right for the Rangers), before the Series traveled to Arlington, Texas, and, in an American League ballpark, Guerrero could play DH. Not that it helped much as Guerrero managed one single, albeit an RBI single, in 14 at-bats for a paltry .071 batting average while striking out five times (he did add a sacrifice fly) as the Rangers fell to the Giants in five games.

And as far as the intangibles go, I got to see Guerrero several times in his prime during his first few seasons with the Angels. Simply put, his was a can't-miss at-bat—you didn't leave your seat to get a hot dog or to use the rest room when you knew he would be coming up soon. Even if Vladdy grounded to short or flied out to center, it was still exciting because there was the potential for magic any time he connected with the ball. I've seen a lot of great hitters in person over the years—Barry Bonds, Manny Ramirez, David Ortiz, Alex Rodriguez—players who are or will be the key names on a Hall of Fame ballot, and not one of them produced as hard a crack off their bat when they hit the ball as did Guerrero—that ringing sound seemed to reverberate through the ballpark. Granted, I saw Guerrero many more times than those visiting stars, but just like them, whenever I saw Guerrero, I felt as if I was looking at an exceptional baseball player. A Hall of Fame-caliber kind of player. And that is where Vladimir Guerrero belongs. He is a Hall of Famer.

With a career split between two teams in the American League Central Division, first the Chicago White Sox from 1997 to 2004, and then the Detroit Tigers from 2005 to 2011, Magglio Ordóñez also found himself sharing the limelight with marquee players, whether Albert Belle and Paul Konerko and Frank Thomas in Chicago or Ivan Rodriguez and Miguel Cabrera in Detroit. Ordóñez also had the bad luck to sign with Detroit as a free agent for the same season, 2005, that saw the White Sox win the World Series for the first time since 1917; he did get to the World Series in 2006, which saw the Tigers lose to the St. Louis Cardinals.

And whether Ordóñez was a Harry Heilmann to someone's Ty Cobb is our examination here. Impacting his career were injuries sustained in 2004 and 2005, his age-30 and -31 seasons, that limited his playing time. In 2007, he did lead the AL in hitting with a gaudy .363 average and in doubles with 54 while placing second in hits (216), total bases (354), on-base percentage (.434), and runs batted in (139) as he was runner-up to Alex Rodriguez in American League Most Valuable Player voting. Ordóñez had one other season in which he finished in the top ten for MVP consideration, 2002, when he posted a .320/.381/.597 slash line while slamming a career-best 38 home runs and driving in 135 runs.

Right fielder Magglio Ordonez posted some big-league numbers--big enough for the Hall of Fame, though?

For an 11-year period from 1999 to 2009, Ordóñez's age-25 to age-35 seasons, he delivered a .315/.376/.521 slash line every year while averaging, per season, 164 hits including 33 doubles and 24 home runs while scoring 82 runs and driving in 97. Over that time, Ordóñez generated, on average, a 131 OPS+ and a 3.4 bWAR each season, and his averages may have looked even more impressive had injuries not limited his playing time in 2004 and 2005, with just 52 games and 222 plate appearances in 2004 and 82 games and 343 plate appearances the following year.

Yet whether in Chicago or Detroit, Ordóñez seemed to be a bridesmaid but never the bride. Becoming a full-time player for the White Sox, Ordóñez competed for attention against Frank Thomas and Albert Belle, and when Belle departed after the 1998 season (in which Belle nearly duplicated his still-unique feat of hitting at least 50 doubles and 50 home runs in the same season, as he did in 1995), young first baseman Paul Konerko began to make his presence felt. Moving to the Tigers in 2005, Ordóñez had been signed as a marquee player, with Ivan Rodriguez, in his age-33 season, the only true position-player star. However, subsequent seasons found Curtis Granderson a young up-and-comer as veteran Gary Sheffield joined the team, the upshot being that Ordóñez was never the linchpin on the two teams he played for.

That perception is borne out in terms of value. As noted above, Ordóñez finished in the top ten for Most Valuable Player twice. In 2007, his best showing, his bWAR was 7.3, his single-best mark, and in 2002, when he placed eighth in voting, he generated a 5.1 bWAR. However, Ordóñez generated a bWAR of 5 wins or better only two other times, with that threshold considered to be All-Star caliber, although he made six All-Star appearances in total. Over his career, Ordóñez generated a bWAR of 38.5 while Jay Jaffe's JAWS (Jaffe's WAR Score system) places him 53rd among all right fielders; FanGraphs is a shade more critical, valuing him at 37.8 wins above a replacement player, while evaluating him at only two seasons with an fWAR of 5.0 or greater.

Magglio Ordóñez had flashes of greatness over his career, and superficially he looks impressive, sporting a career .309/.369/.502 slash line, a 125 OPS+, 2156 hits, 426 doubles, 294 home runs, 1076 runs scored, and 1236 runs batted in. But just as Ordóñez was overshadowed by his more impressive teammates over the course of his career, his playing record is overshadowed by many of the 24 right fielders already in the Hall of Fame. Furthermore, Jose Canseco's claim to have injected Ordóñez with steroids in 2001, although a relative non-starter (for example, Ordóñez's name does not appear in the Mitchell Report), could come back to haunt him. In any case, Magglio Ordóñez lacks the qualifications for the Hall of Fame.

Along with shortstop Derek Jeter and pitchers Andy Pettitte and Mariano Rivera, catcher Jorge Posada is one of the "Core Four," the quartet of New York Yankees whose careers all coincided and who are considered to be the backbone of the emergent Yankees dynasty that in 1996 won its first World Series in 18 years, and, for a seven-year period after that championship, returned to the World Series five more times, winning three Series in a row between 1998 and 2000. Moreover, Posada joins a long and distinguished line of Yankees catchers, starting with Bill Dickey and continuing through Yogi Berra—both are Hall of Famers—Elston Howard, and Thurman Munson.

As the back-up catcher to Joe Girardi, though, Posada was brought along slowly. From 1997 to 1999, he started 52, 85, and 98 games as catcher, respectively, getting 136 starts in 2000, his age-28 season, when Girardi left to sign with the Chicago Cubs as a free agent. Posada remained the Yankees' full-time catcher for another seven seasons, and for an eight-year period from 2000 to 2007 Posada posted a .283/.389/.492 slash line, averaging per season 137 hits including 31 doubles and 23 home runs as he generated a 130 OPS+ and a 4.5 bWAR while scoring an average of 76 runs and driving 90 per season. Posada had two seasons with 40 or more doubles, joining Ivan Rodriguez as the only two catchers in baseball history to accomplish this feat, and he hit at least 20 home runs in every year during this period except 2005 when he fell one shy of that plateau, while his 30 round-trippers in 2003 were a career-best.

Indeed, the switch-hitting Posada was considered an offensive catcher. He earned five Silver Slugger awards at the position while placing among the top five for American League Most Valuable Player twice. His 2003 campaign was his best year: He delivered a .281/.405/.518 slash line, good for a 144 OPS+, and his 30 home runs and 101 RBI were also career-bests. Posada was third in MVP voting that season, behind Alex Rodriguez and Carlos Delgado. He placed sixth in MVP voting in 2007 when he batted .338, fourth-best in the AL and the only time he hit .300 or better, based on a career-high 171 hits that included 20 home runs and a career-best 42 doubles, and he reached base at a career-best .426 clip, good for third in the AL. Rounding out his slash line was his .543 slugging percentage, another career mark and eighth overall in the AL, while his 153 OPS+, yet another career high-water mark, was good for fifth in the AL that season. Posada was named to the 2007 AL All-Star squad for the fifth and final time.

Then shoulder surgery sidelined him in 2008, his age-36 year, as he managed just 51 games overall. He returned to form in 2009, as in 88 starts as catcher and in 438 plate appearances he produced a .285/.363/.522 slash line, generating a 125 OPS+, with 25 doubles, 22 home runs, and 81 RBI. But Posada's decline had begun—following the 2010 season, a disappointing offensive campaign, he had knee surgery, and in his final season in 2011 he was used as the Yankees' designated hitter with a handful of starts at first base. The 2011 season also saw a slumping Posada remove himself from the lineup after being listed as the number-nine hitter for a mid-May game against the Boston Red Sox, and although he hit well in June, by August he was riding the bench. Ironically, Posada hit .429 as the Yankees' DH during the AL Divisional Series against the Detroit Tigers, a series the Yankees lost in five games, but when the Yankees, the only major-league team Posada had played for, showed no interest in him for the 2012 season, he retired.