Index

Golden Era Hall of Fame First Basemen

Because these nine player candidates have been identified as belonging to the Golden Era, it may be useful to compare them with their Golden Era contemporaries already in the Hall of Fame. So, starting with this segment and in the following segments, I have grouped each of the nine player candidates with the Hall of Fame players that also played the same position as the candidate. The exception is Dick Allen, who played both first base and third base and is included in the comparisons of Hall of Fame players at both positions; although Allen played more games at first base, Jay Jaffe's JAWS statistics lists him as a third baseman because he provided the greatest value at third.The Hall of Fame players were selected if they played the majority of their careers during the pre-defined Golden Era. I used 1964 as the latest first-year date for the Hall of Fame players because that is the first-year date for Luis Tiant, who had the latest start of the nine candidates.

The purpose of this is simple: If these nine player candidates are to be considered Hall of Fame players from baseball's Golden Era, how do they stack up against other Fame players from that Golden Era who already have been inducted into the Hall of Fame?

Let's start with first base. Here are the five Hall of Fame first basemen associated with the Golden Era and 2015 Golden Era first-base candidates Dick Allen and Gil Hodges, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame First Basemen and 2015 First Basemen Candidates on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| McCovey, Willie |

.270/.374/.515 |

.388 |

64.4 |

67.4 |

147 |

145 |

| Killebrew, Harmon |

.256/.376/.509 |

.389 |

60.3 |

66.1 |

143 |

142 |

| Allen, Dick |

.292/.378/.534 |

.400 |

58.7 |

61.3 |

156 |

155 |

| * Torre, Joe |

.297/.365/.452 |

.365 |

57.6 |

62.3 |

129 |

129 |

| Perez, Tony |

.279/.341/.463 |

.356 |

53.9 |

58.9 |

122 |

121 |

| Cepeda, Orlando |

.297/.350/.499 |

.370 |

50.2 |

50.3 |

133 |

131 |

| Hodges, Gil |

.273/.359/.487 |

.378 |

44.9 |

42.1 |

120 |

121 |

Among their Golden Era contemporaries, Allen compares quite favorably to Willie McCovey and Harmon Killebrew in percentages (slash line, wOBA), value (WAR), and league- and park-adjusted indexes (OPS+, wRC+). In fact, in this sample, Allen is tops in on-base percentage, slugging percentage, wOBA, OPS+, and wRC+. Hodges, on the other hand, lags behind all others in terms of value, and is most comparable to Tony Perez, who is a very marginal Hall of Famer, and whose eventual election by the BBWAA in 2000 is likely due to his being a key component of the Cincinnati Reds' "Big Red Machine" as much as his individual excellence. This is an angle that applies to Hodges's case, as we will examine shortly.

The table below lists the five Hall of Fame first basemen associated with the Golden Era along with Allen and Hodges, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all first basemen in the Hall of Fame.

| 2015 Golden Era First Basemen Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame First Basemen (Ranked by bWAR) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Ave of 19 1B HoFers |

NA |

NA |

NA |

65.9 |

42.4 |

54.2 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| McCovey, Willie |

22 |

1959 |

1980 |

64.4 |

44.8 |

54.6 |

12 |

110 |

44 |

| Killebrew, Harmon |

22 |

1954 |

1975 |

60.3 |

38.1 |

49.2 |

19 |

178 |

46 |

| Allen, Dick |

15 |

1963 |

1977 |

58.7 |

45.9 |

52.3 |

NA |

99 |

39 |

| Torre, Joe |

18 |

1960 |

1977 |

57.6 |

37.3 |

47.5 |

22 |

96 |

40 |

| Perez, Tony |

23 |

1964 |

1986 |

53.9 |

36.4 |

45.2 |

26 |

81 |

41 |

| Cepeda, Orlando |

17 |

1958 |

1974 |

50.2 |

34.5 |

42.4 |

30 |

126 |

37 |

| Hodges, Gil |

18 |

1943 |

1963 |

44.9 |

34.2 |

39.6 |

34 |

83 |

32 |

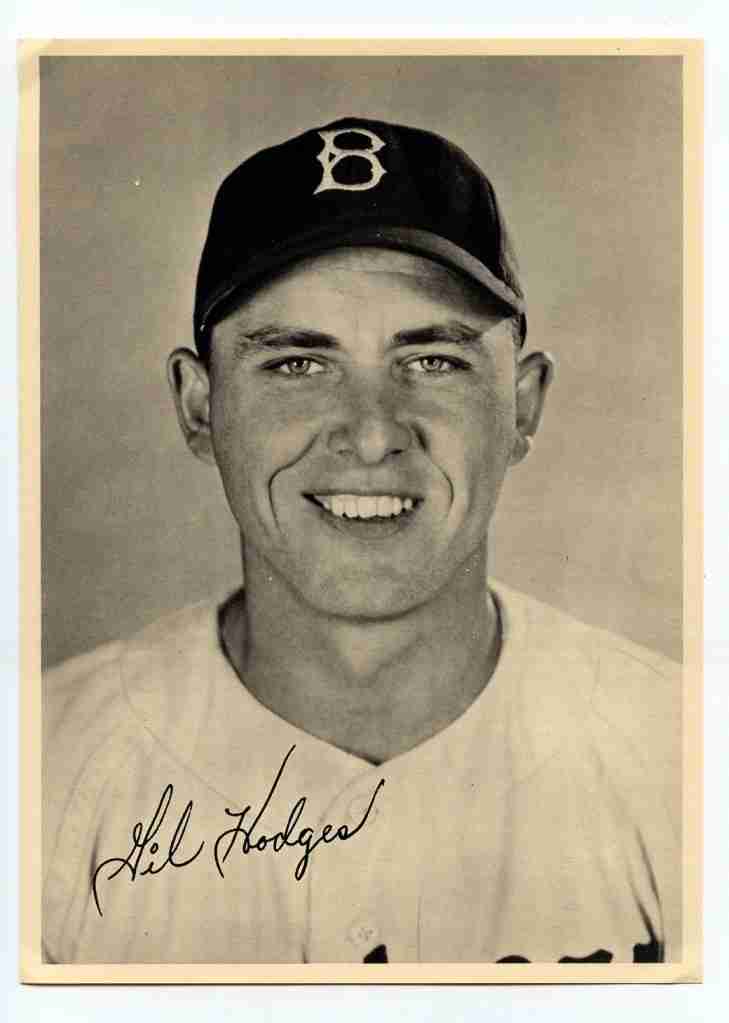

In terms of personality and temperament, Dick Allen and Gil Hodges are poles apart. We will examine Allen more closely in the third baseman segment below. In this segment, we will examine Hodges more closely.

Gil Hodges and "The Boys of Summer"

Gil Hodges is a sentimental favorite for the Hall of Fame—he polled nine of sixteen votes in the last Golden Era Committee ballot—and that sentiment that has been in part fostered and perpetuated by Roger Kahn's 1972 hagiography about the Brooklyn Dodgers, The Boys of Summer. That keynote book profiled the team up to their 1955 World Series victory in relation to Brooklyn native Kahn's life and career as a reporter and writer. Kahn's gushing paean to the "Bums" still informs "the boys of summer," four of whom were Hodges's teammates during this period and who have been enshrined in the Hall of Fame—where, Hodges's supporters insist, Hodges belongs as well.

But does Hodges stack up against his teammates Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, and Duke Snider? The following table lists the qualitative statistics of these Hall of Fame "boys of summer" along with Hodges's.

| Brooklyn Dodgers Golden Era Hall of Fame Position Players and Gil Hodges, Qualitative Statistics Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Snider, Duke |

.295/.380/.540 |

.404 |

66.5 |

63.5 |

140 |

139 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

.269/.366/.377 |

.350 |

66.3 |

64.4 |

99 |

103 |

| Robinson, Jackie |

.311/.409/.474 |

.406 |

61.5 |

57.2 |

132 |

135 |

| Hodges, Gil |

.273/.359/.487 |

.378 |

44.9 |

42.1 |

120 |

121 |

| Campanella, Roy |

.276/.360/.500 |

.385 |

34.2 |

38.2 |

123 |

123 |

| Brooklyn Dodgers Golden Era Hall of Fame Position Players and Gil Hodges, Hall of Fame Comparison Statistics (Ranked by bWAR) |

||||||||||

| Player |

Pos. |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Snider, Duke |

CF |

18 |

1947 |

1964 |

66.5 |

50.0 |

58.2 |

7 |

152 |

47 |

| Reese, Pee Wee |

SS |

16 |

1940 |

1958 |

66.3 |

41.0 |

53.6 |

17 |

100 |

39 |

| Robinson, Jackie |

2B |

10 |

1947 |

1956 |

61.5 |

52.1 |

56.8 |

10 |

98 |

38 |

| Hodges, Gil |

1B |

18 |

1943 |

1963 |

44.9 |

34.2 |

39.6 |

34 |

83 |

32 |

| Campanella, Roy |

C |

10 |

1948 |

1957 |

34.2 |

32.8 |

33.5 |

25 |

108 |

39 |

In both sets of data, Hodges generally ranks behind all his "boys of summer" contemporaries except for Roy Campanella, whose slash line, wOBA, OPS+, and wRC+ are roughly equivalent to Hodges's. Campanella, though, suffered misfortune at both ends of his short career: A Negro League player, Campanella's first Major League season was in 1948, following integration the previous year, in his age-26 year. Then, tragically, his career ended following a January 1958 automobile crash that left him paralyzed for the rest of his life. That occurred in what would have been his age-36 year.

Had Campanella not been injured, it is intriguing to consider what the Dodgers would have done with both Campanella and Hodges. As a catcher, Campanella was already in his decline phase before he was injured—in 1957 he started 94 games at catcher, his lowest number since his rookie season—and whether he would have continued as a catcher or have been traded away are points of speculation. However, the Dodgers could have considered moving him to first base—and where would that have left Hodges? Let's note that Hodges had come up as a catcher but was moved to first base to accommodate Campanella. Would Hodges have been moved off first base to accommodate Campanella again?

Again, that is a what-if situation, but it gets to the question of relative value, and of Hodges's specific value. Roy Campanella was named the National League's Most Valuable Player three times (1951, 1953, 1955) during his ten-year career (we'll leave aside whether he deserved the honors), and he finished in the top ten for MVP voting one other time. Jackie Robinson was the NL MVP in 1949, and he finished in the top ten for MVP voting in two other years; Robinson was also the 1947 NL Rookie of the Year—the award is now named for him. Pee Wee Reese was never named MVP but he finished in the top ten for MVP voting eight times. Similarly, Duke Snider was never an MVP but he finished in the top ten six times, with three of those top-five finishes. Hodges had three top-ten MVP-voting finishes and never won the award.

Snider had five consecutive years in which he hit 40 or more home runs, leading the NL in 1956 with 43, and he drove in 100 or more runs six times, leading the NL with 136 in 1955. Hodges hit 40 or more home runs twice and drove in 100 or more runs in seven consecutive seasons, although he never led the league in either category. Campanella hit 41 home runs in 1953, the only time he reached that plateau, while driving in a league-leading 142 runs in that same season, one of three times that he reached that plateau. Campanella, Hodges, and Snider were power-hitting, middle-of-the-order players and are more easily compared to each other, although Robinson, who was not primarily a home-run hitter, actually played more games batting in the cleanup position, and his OPS+ and wRC+ are better than Hodges's. Reese was a table-setter at the top of the order, and his offensive stats cannot match closely to Hodges's—although Reese's batting average and on-base percentage are comparable.

But catcher Campanella, shortstop Reese, second baseman Robinson, and center fielder Snider staffed the core defensive positions up the middle while Hodges was a first baseman, the least demanding defensive position. Granted, Hodges was an excellent-fielding first baseman, winning the first three Gold Glove Awards at that position when the award was introduced in 1957—a greater honor in that inaugural year as the award was presented to only one player at each position across both leagues. However, Hodges's career Range Factor scores are actually lower than the league averages for each statistic: For Range Factor per 9 innings, Hodges posted a 9.56 versus the league's 9.75, and for Range Factor per Game, Hodges had an 8.71 versus the league's 9.67. (For Range Factor per 9 Innings, the equation is put-outs plus assists multiplied by 9, then divided by the number of innings played; for Range Factor per Game, the equation is put-outs plus assists divided by the number of games played.)

Hodges may have been overshadowed by his "boys of summer" teammates, but that is for good reason: Hodges simply wasn't as good as they were in terms of the Hall of Fame. His WAR, JAWS, Hall of Fame Monitor, and Hall of Fame Standards statistics show that he is not even close to the thresholds in comparison either to his storied teammates or to Golden Era first basemen already in the Hall. Aside from the fulsome sentimentality exemplified by Roger Kahn's book, there seems to be a "complete the set" mentality concerning Hodges—all his star "boys of summer" teammates are in the Hall, so why isn't Hodges? That seems to have been the case for Tony Perez, whom even BBWAA voters thought should join his "Big Red Machine" teammates Johnny Bench and Joe Morgan (and presumably Pete Rose should he have been eligible) when they voted Perez into the Hall in 2000. (Coincidentally, the Veterans Committee voted Reds manager Sparky Anderson into the Hall that same year.)

As we have seen in the comparisons above, Hodges and Perez are pretty close to each other in a number of categories. Perez hit for a slightly better average, but Hodges got on base and slugged at a higher percentage. In counting numbers, though, Perez has the edge as he is in the top 60 lifetime in a few key categories: He ranks 57th in hits with 2732 (Hodges ranks 315th with 1921), 55th in doubles with 505 (Hodges is 446th with 295), and 28th in runs batted in with 1652 (Hodges is 125th with 1274), although Perez had more than 2600 more plate appearances than did Hodges, which makes Hodges's 370 home runs to Perez's 379 look that much more impressive. But neither Hodges nor Perez are Hall-worthy.

Where Hodges has another claim to the Hall is as a manager. Following his player retirement during the 1963 season, Hodges became the manager of the Washington Senators until 1967 before becoming the manager of the New York Mets for the 1968 season. The Senators did not have a winning season under Hodges, although in four full seasons the team improved steadily to a 76–85 (.472) mark in 1967. Similarly, the Mets were also a sub-.500 club under him during his first year in New York, but in 1969 Hodges took the "Miracle Mets," who won 100 games and took the National League Pennant, all the way to the World Series, which they won in five games against the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles. Hodges was named The Sporting News Manager of the Year, which in 1969 awarded the honor to only one manager across both leagues. (Note that in 1983 the BBWAA, which votes for Rookie of the Year, Cy Young, and Most Valuable Player awards, instituted its own Manager of the Year award although The Sporting News continues to present its award, and since 1986 it is presented to a manager in each league.)

Here the comparison is to Joe Torre, a near-Hall of Famer as a player who went on to an auspicious managing career, which landed him in the Hall of Fame in 2014. But just as we saw above that Torre's playing record is superior to Hodges's, there is no comparison as a manager. Torre ranks fifth all-time among managers in wins with 2326, against 1997 losses for a .538 winning percentage, winning six pennants along the way. and Torre posted a 84–58 mark (.592) in the postseason, winning four World Series with the New York Yankees; those 84 postseason wins are the best all-time (taking into account that they all came during the current Divisional Era with its three rounds of postseason play, thus greatly expanding the number of postseason games in a season). Hodges posted a 660–753 record (.467) as a manager with one pennant won and one World Series won. Hodges died in 1972, two days shy of his 48th birthday, and thus there is no way to know what Hodges could have accomplished as a manager had he lived.

But you evaluate the baseball you have, not the baseball you wish you had. Hodges's playing record and managing record are not sufficient to call him a Hall of Famer, either singly or together.

Golden Era Hall of Fame Third Basemen

In this segment, we examine the two third basemen candidates named on this year's Golden Era ballot, Dick Allen and Ken Boyer. Allen was evaluated in the preceding segment that examined first basemen as Allen played more games at first base (795 games started; 571 complete games) than at third base (646 games started; 593 complete games). However, Jay Jaffe's JAWS ratings place Allen at third base because he produced his greatest value as a third baseman.Here are the four Hall of Fame third basemen associated with the Golden Era and 2015 Golden Era third-base candidates Dick Allen and Ken Boyer, ranked by bWAR, with other qualitative statistics, including fWAR, listed alongside it.

| Golden Era Hall of Fame Third Basemen and 2015 Third Basemen Candidates on the 2015 Golden Era Ballot, Ranked by bWAR |

||||||

| Position Player |

Slash Line |

wOBA |

bWAR |

fWAR |

OPS+ |

wRC+ |

| Mathews, Eddie |

.271/.376/.509 |

.389 |

96.4 |

96.1 |

143 |

143 |

| Robinson, Brooks |

.267/.322/.401 |

.322 |

78.3 |

80.2 |

104 |

104 |

| Santo, Ron |

.277/.362/.464 |

.367 |

70.4 |

70.9 |

125 |

126 |

| Boyer, Ken |

.287/.349/.462 |

.355 |

62.8 |

54.8 |

116 |

116 |

| Allen, Dick |

.292/.378/.534 |

.400 |

58.7 |

61.3 |

156 |

155 |

| Kell, George |

.306/.367/.414 |

.362 |

37.6 |

38.2 |

112 |

111 |

Boyer, on the other hand, has been considered a poor man's Ron Santo, and as the slash lines above indicate, they are very similar—Boyer hit for a better average, Santo had a better on-base percentage (he led the National League in that category twice and in walks four times), and their slugging averages are a wash. Both played for 15 seasons, but Santo played in roughly 200 more games with about 1100 more plate appearances, which gives him the edge in counting numbers (hits, doubles, home runs, runs scored and runs batted in). Boyer won the NL Most Valuable Player award in 1964 when he led the NL in RBI with 119.

Both third basemen won five Gold Gloves each. Boyer was probably the better defensive third baseman: Baseball Reference calculates his defensive Wins Above Replacement (dWAR) at 10.6 while Santo's is 8.6, and the site calculates Boyer's Total Zone Total Fielding Runs above Average, the number of runs above or below average a fielder was worth based on the number of plays made, at 73 while Santo clocks in at 20. FanGraphs gives Boyer the edge over Santo in Defensive Runs Above Average (the number of runs above or below average a fielder is worth on defense; it combines fielding runs and positional adjustment), with Boyer's 105.7 topping Santo's 69.5, although—oddly—FanGraphs rates Santo higher in Total Zone Number of Runs Saved, with Santo indexed at 27 while Boyer is at 7.

Defensively, Allen is a tremendous hitter. Allen's overall dWAR is –16.5 while his overall Defensive Runs Above Average is –152.2; at third base, Allen rates a –45 in Total Zone Total Fielding Runs above Average and a –46 in Total Zone Number of Runs Saved.

The table below lists the four Hall of Fame third basemen associated with the Golden Era along with Allen and Boyer, ranked by bWAR, along with their JAWS statistics and ratings for the Hall of Fame Monitor and the Hall of Fame Standards. Also included are the JAWS statistics for all third basemen in the Hall of Fame.

| 2015 Golden Era Third Basemen Candidates, Qualitative Comparisons to Hall of Fame Third Basemen (Ranked by bWAR) |

|||||||||

| Player |

No. of Years |

From |

To |

bWAR |

WAR7 |

JAWS |

JAWS Rank |

HoF Mon. (≈100) |

HoF Std. (≈50) |

| Mathews, Eddie |

17 |

1952 |

1968 |

96.4 |

54.3 |

75.4 |

2 |

162 |

54 |

| Robinson, Brooks |

23 |

1955 |

1977 |

78.3 |

45.8 |

62.1 |

8 |

152 |

34 |

| Santo, Ron |

15 |

1960 |

1974 |

70.4 |

53.8 |

62.1 |

7 |

88 |

41 |

| Ave of 13 HoFers |

NA |

NA |

NA |

67.4 |

42.7 |

55.0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Boyer, Ken |

15 |

1955 |

1969 |

62.8 |

46.3 |

54.5 |

14 |

86 |

36 |

| Allen, Dick |

15 |

1963 |

1977 |

58.7 |

45.9 |

52.3 |

17 |

99 |

39 |

| Kell, George |

15 |

1943 |

1957 |

37.6 |

27.8 |

32.7 |

48 |

90 |

29 |

Ken Boyer is a promising candidate but doesn't quite measure up as a deserving Hall of Fame inductee. Dick Allen is a more intriguing proposition.

The Intriguing if Troubled Career of Dick Allen

Beginning his career in the mid-1960s, Allen is a fitting presence in that turbulent decade—controversial, outspoken, misunderstood, and ultimately mistreated. As an African-American, Allen endured racial harassment even before he joined the Philadelphia Phillies as he became the first black player on the Phillies' minor-league affiliate in Little Rock, Arkansas, at the time still one of the most racially divisive regions in the United States. (Recall that only a few years before, in 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus had called out the state National Guard to prevent the integration of Little Rock Central High School, a move that was countered by President Dwight Eisenhower when he sent federal troops to Little Rock to ensure the students' safety.)

But when Allen joined the parent club for his first full season in 1964, he merely became the National League's Rookie of the Year when he led the league in runs (125), triples (13), and total bases (352)—and also strikeouts (138)—while collecting 201 hits, slugging 38 doubles and 29 home runs, posting an impressive slash line of .318/.382/.557, generating a 162 OPS+, and driving in 91 runs. Allen was one of the true bright spots in a season that saw the Phillies, who had been in first place for most of the season, fall into a horrendous slump during the final weeks of the season and lose the pennant, one of the most notorious collapses in baseball history. Yet Allen did not endear himself to Phillies fans—indeed, not only did they hurl insults and racial epithets at him, they began to hurl physical objects at him, prompting Allen to wear a batting helmet as he played the field, which earned him the nickname "Crash," short for "crash helmet." Even his teammates threatened him, such as Frank Thomas (not the 2014 Hall of Fame inductee), a known racist who wielded a bat at Allen in an infamous 1965 incident that saw Thomas ejected from the team.

As a result, Allen demanded to be traded from the Phillies. He was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals (who had eventually taken the NL pennant in 1964, with its own third baseman, Ken Boyer, winning the MVP award) in 1970, and found himself again a part of history: One of the players for whom he was traded was Curt Flood, who famously refused to be traded without his consent; Flood's protest, though ultimately futile, did eventually lead to the dismantling of baseball's Reserve Clause and to the current free-agency environment. Allen's short stay in St. Louis was relatively uneventful, and he was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers, for whom he played one season before being dealt to the Chicago White Sox. (He was traded for Tommy John, who himself would make history for the arm surgery now named for him.)

In his first year with the White Sox, Allen owned the American League: He led the AL in home runs (37), RBI (113), bases on balls (99), on-base percentage (.420), slugging percentage (.603), and, retrospectively, OPS+ (199) while batting .308 and even stealing 19 bases, one shy of his career-high 20 in 1967. Allen walked away with the MVP award, garnering 21 of the 24 first-place votes, and was certainly the best position player in the league that year. But a serious leg injury curtailed his 1973 season, and although he rebounded the following year, his age-32 season, with a .301/.375/.563 slash line and a league-leading 32 home runs (he also led the AL in slugging percentage), Allen quit the White Sox with two weeks to go in the 1974 season, claiming a feud with Ron Santo, in his last season before retirement, was to blame. Allen announced his own retirement following the season, but he was lured back to, of all places, Philadelphia. However, his previous injury and the onset of his decline phase meant that Allen had seen his best seasons already pass him by. He retired for good following the 1977 season, after an undistinguished part-time year with the Oakland Athletics.

In terms of offensive effectiveness, Dick Allen is probably the most potent of the six position-player candidates on the Golden Era ballot. Minnie Miñoso and Tony Oliva could hit for average and get on base, and Gil Hodges hit more home runs (370) than did Allen (351), but Allen could do all of that impressively—and he is the only one of the six with a slugging percentage above .500. Allen's counting numbers cannot match up with career leaders, and apart from his sensational 1964 rookie season and his masterful 1972 MVP season, Allen did not have a streak of dominance that would indicate an incipient Hall of Fame talent; apart from his rookie campaign and his MVP season, he had only one other year in which he finished in the top ten for MVP voting: in 1966, when he placed fourth after generating a .317/.396/.632 slash line—that .632 slugging average led the NL—hitting 40 home runs, and driving in 110 runs.

Offensively, Dick Allen is the best candidate on the 2015 Golden Era ballot, but he falls just short of the Hall of Fame.

Comments powered by CComment