Well, spring is here, and we have no baseball because of the ongoing COVID-19 (Coronavirus) pandemic, and given its novelty and presumptive early stages, it is anyone's guess when baseball (let alone any social activity involving two or more persons in proximity to each other) will return. But instead of staring out the window, you can get your baseball fix by watching movies about the national pastime.

Perhaps more so than any other team sport, baseball's very nature—contemplative and anticipatory, individualistically focused, with the unlikeliest reversals of fortune—lends itself not only to drama, but to drama that is captured effectively by the moving camera. That might sound ironic given that the age-old knock against baseball is that nothing ever happens, that players just stand around waiting for something to happen, which has prodded Major League Baseball to implement "adjustments" designed to speed up the pace of play.

Whether those will be successful remains to be seen. However, "pace of play" is not the same as baseball's mode of play, which has remained essentially the same since 1839, when Abner Doubleday invented baseball in Cooperstown, New York, now the site of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum—

—All right, you caught me. No, Doubleday didn't invent baseball, but that myth, which may still persist among the uninitiated, exemplifies the storytelling, colorful, prone to embellishment if not outright exaggeration, that has been emblematic of baseball since before movies were invented.

Baseball fans, even casual ones, know that something does happen on the diamond, that action occurs in concentrated doses in between those bouts of "standing around"—but that "standing around" is nevertheless filled with contemplation: What will happen next? What will the consequences be? Not coincidentally, those are also the hallmarks of movie-making, of the many variations of the setup and the payoff in building an engaging dramatic (or comedic) narrative.

Central to baseball's mode of play is the pitcher-hitter confrontation, with the pitcher trying to get the hitter out and the hitter, naturally, trying to avoid that outcome by getting on base, and thus to score runs. There is potential action—and inherent drama—hanging on every pitch, and depending on the game situation, let alone the magnitude of the game itself, that drama can be magnified to cinematic proportions.

How is this for magnitude: In 2004, the Boston Red Sox, playing at home in Fenway Park, have dropped the first three games of the American League Championship Series to the New York Yankees, their adversaries in the most storied rivalry in baseball, the same Yankees who in Game Seven of the ALCS from the previous year had foiled Boston's hopes to return to the World Series for the first time since 1986 with—cue the slow-motion cameras—Aaron Boone's dramatic walk-off home run off Tim Wakefield.

Now, in Game Four of the 2004 ALCS, the Red Sox face elimination going into the bottom of the ninth inning, down one run in a 4–3 game with leadoff hitter Kevin Millar having to face the Yankees' ace closer Mariano Rivera. Lo, Millar is able to work a walk off the "Sandman," and he is lifted for pinch-runner Dave Roberts—with everybody in the world, certainly Rivera, knowing that Roberts's job was to steal second base.

He did, off the greatest relief pitcher in Major League history, enabling Bill Mueller to single him home to tie the game, which the Red Sox won in extra innings on David Ortiz's twelfth-inning, two-run home run blast. From there, the Red Sox became the only MLB team ever to win a seven-game postseason series after losing the first three games, and then went on to sweep the St. Louis Cardinals for their first World Series victory since Babe Ruth blew town—for New York and the Yankees—in 1918. Talk about drama.

And as Roberts was stealing the most famous base in Red Sox history, how many viewers were reminded of Benny "the Jet" Rodriguez (played by Pablo Vitar as the adult Benny) stealing the one base he had to steal in the 1993 movie The Sandlot?

It's not simply art imitating life, or in this case vice versa. Baseball lends itself to movies because no player, not even a bench player like Roberts, is ever anonymous. Even just "standing around," whether at the plate, in the field, on a base (like pinch-runner Roberts), and certainly on the mound, as any pitcher always has the spotlight on him, players start to become characters—and over its many decades, baseball has seen a wealth of characters.

Quick: Name an offensive lineman who protected New England Patriots' quarterback Tom Brady? Or name a Detroit Red Wings forward on any other line at the time of the famous, original Gordie Howe-Ted Lindsay-Sid Abel "Production Line"? Sure, fans of those teams, or of football or hockey in general, have a good shot at it. But baseball, especially in the postseason, can put the lasting spotlight on any player, great or small, because of his feats, whether for a season (Mark Fidrych in 1976), a series (Bucky F. Dent in the 1978 World Series), a game (Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series), or even one at-bat (Kirk Gibson as a hitter in the 1988 World Series; Pete Alexander as a pitcher in the 1926 World Series).

All these elements, the constant pitcher-hitter confrontation, the spotlight inevitably touching everyone on the field (think of even the late-inning defensive replacement and of how quickly the ball will find him), and the magnitude of the game situation or of the importance of the game itself, combine to lend themselves to movies.

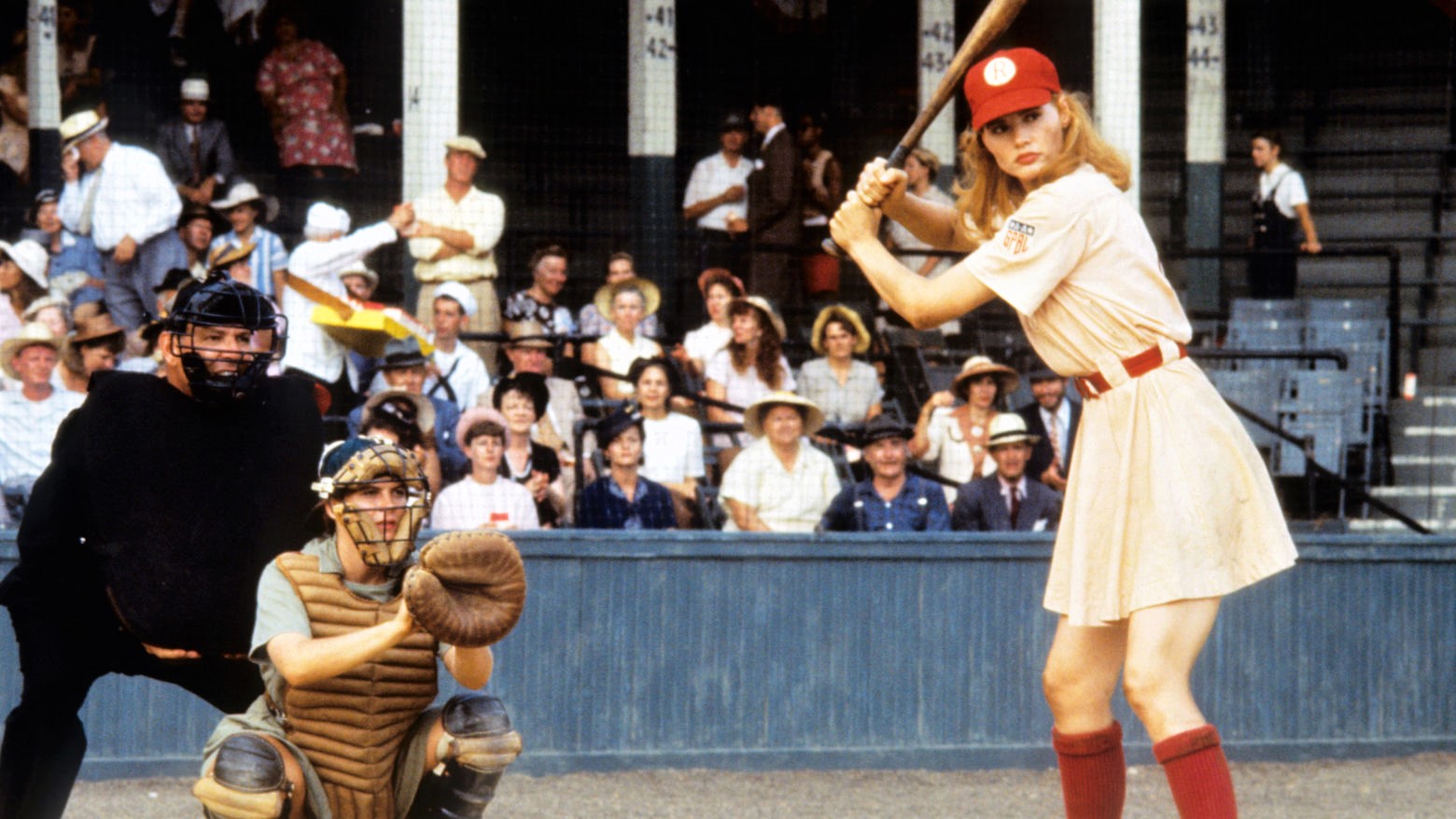

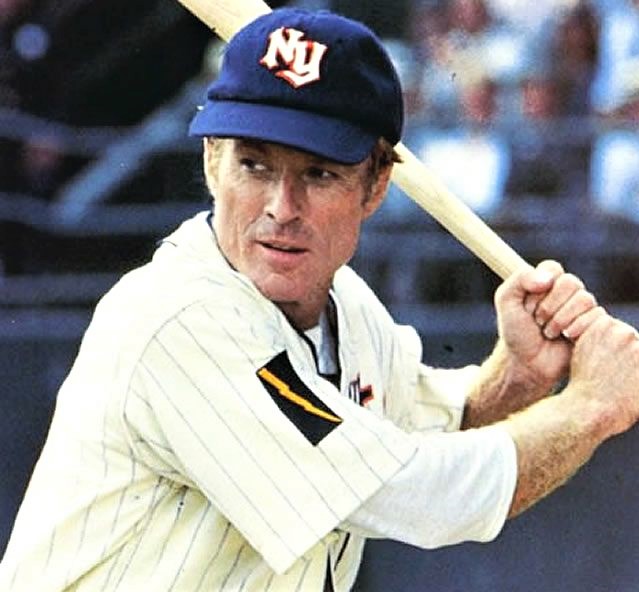

Yes, many other sports have their epic—and not-so-epic—movies too, but that "standing around" in baseball is the contemplation before the action, the tension, then release, the setup and the payoff that feeds into a dramatic (or comedic) narrative, whether it's Robert Redford's Roy Hobbs, hobbling from the Grim Reaper, displaying his literal light-tower power at the climax of The Natural, or Lori Petty's Kit Keller, battling both the high fastball and her sibling rivalry, hitting a gapper, then running through the stop sign at third to barrel into Geena Davis's catcher Dottie Hinson—her sister and erstwhile teammate—at the plate in A League of Their Own.

And baseball movies don't even need to have "the big game" as the climax. Bull Durham certainly doesn't have one, and given that the action is set in the minor leagues, there isn't even any big-league excitement to begin with. Instead, it focuses on three distinct characters including Kevin Costner's Crash Davis, a career minor-leaguer with a good shot to reach a largely unheralded accomplishment, Tim Robbins's Nuke Laloosh, a young "pheenom" with a good shot to reach the Majors—and Susan Sarandon's "Baseball Annie" Savoy, who isn't even a player but who probably knows more about the church of baseball than the two of them put together.

Charter members of the Church of Baseball (L-R): Tim Robbins ("Nuke LaLoosh"), Susan Sarandon ("Annie Savoy"), and Kevin Costner ("Crash Davis") in Bull Durham.

The relative handful of baseball movies evaluated here are representative of baseball movies overall, from early talkies to contemporary releases, from dramatizations of actual players or events to fanciful depictions, and from classics to obscurities. And since we love our sample sizes in baseball, I won't claim that this sampling is in any way definitive, although several of the best-known baseball movies over the decades are evaluated—and like a good sabermetric analysis, you might be surprised—even angered—at those I consider overrated and underrated.

Furthermore, all of them are feature films, so there are no documentaries, which can number well into the hundreds, if not thousands, if you count television and promotional documentaries (for example, the obligatory annual reports from teams on their seasons, particularly if they won the World Series) and not simply "event" documentaries such as Ken Burns's two landmark series on Baseball.

But even narrowing the categories still keeps this list representative, not definitive, because there are still quite a few more than the ones I've actually seen. And speaking of movies that I have seen, there are a few that I have not seen in so long that it would be unfair to fully evaluate them based on fuzzy memory. Among those are the aforementioned The Sandlot along with Bang the Drum Slowly (1973) and Little Big League (1994), and since I was unable to see them again while writing this article, they are not evaluated here. (However, if you want my quick take based on that fuzzy memory: The Sandlot is schmaltzy, Bang the Drum Slowly is sappy, and Little Big League is surprisingly snappy.)

And speaking of evaluations . . . because as baseball fans we all love our statistics, and for this evaluation I am using WAR. No, I don't mean Wins Above Replacement, but rather Wholesale Attractiveness Rating. This WAR encompasses aspects of both baseball and filmmaking, meaning, in essence, that the baseball action needs to be credible to the average viewer, the movie production has to be professional, and the narrative, both in concept (baseball inspiration) and execution (filmmaking expertise), has to be effective.

Wholesale Attractiveness Rating (WAR)

|

5.0 WAR |

Hall of Famer. Transcendent filmmaking or storytelling that epitomizes a period or style of the genre. |

|

4.0 WAR |

All-Star. Superior but not transcendent filmmaking or storytelling. |

|

3.0 WAR |

League-Average. Filmmaking or storytelling of average value, or typical of a period or style of the genre. |

|

2.0 WAR |

Designated for Assignment. Fundamentally flawed technically and/or artistically, or an interesting failure. |

|

1.0 WAR |

Try a Career in Sales. Technically inferior and/or artistically bankrupt; no redeeming qualities. |

Sure, it's subjective, and I'm not fooling anyone by trying to disguise a five-star rating system with these WAR trappings. In that respect, since I don't use half-stars in a five-star rating system but baseball's actual WAR uses decimal values as part of its legacy in Win Shares, these movie WAR ratings have decimals that may indicate a minor matter of degree, but what matters is the value to the left of the decimal point; in other words, a 2.9 WAR does not round up to 3.0; as Clifton James's Charles Comiskey tells David Strathairn's Eddie Cicotte in Eight Men Out, "Twenty-nine [wins] is not thirty, Eddie." And thus the fix begins for the "Black Sox" scandal during the 1919 World Series, but we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Twenty-nine isn't thirty, Eddie: White Sox pitcher Eddie Cicotte (David Strathairn, pitching) becomes a key conspirator in the 1919 "Black Sox" World Series scandal in Eight Men Out.

Final notes on the ratings: Only two movies in this evaluation are Hall of Fame movies with the 5.0 WAR. Just as it is (or should be) hard to get into the real National Baseball Hall of Fame (unless your name is Harold Baines, but I digress), so too is it hard to get that highest WAR—and, to be honest, I did fudge one rating to get to that 5.0 WAR for a movie I consider to be a four-star film elsewhere just so the sole five-star/5.0 WAR film has some company.

On the other hand, no movie in this evaluation gets the dreaded 1.0 WAR—although I was sorely tempted by one "classic" baseball movie—because any baseball movie no matter how mediocre is better than none. Particularly during a time when we don't even know when baseball, let alone any other aspect of our lives, will "get back to normal."

And—last word on ratings—"league-average" is not an insult, either in baseball or in movies. It simply means that the item described as such belongs in the "league," whether it's a player in the Major Leagues or a movie that you would pay money to see in a cinema. And given how much a movie ticket costs these days, "league-average" is worth it considering your investment in time and money to see the movie.

Just as baseball has experienced many eras, from its formative stages in the 19th century to the beginning of "the modern game" in 1901, its transition from "dead ball" to "live ball" by 1920, its incremental league expansion beginning in 1961, the introduction of the tiered playoff structure in 1969, and the institution of the designated hitter in the American League in 1973, so too have movies undergone their evolutionary stages: Movies transitioned from silent film to "talkies" by 1930, endured the gradual imposition of the Production Code (restrictions on what could be shown, and how, in a movie, based on arbitrary moralism) a few years later, and enjoyed the increasing development of color photography before seeing the gradual elimination of the Production Code starting in the 1960s, which accompanied the gradual diminishment of studio-system dominance that had prevailed since the 1920s; meanwhile, movies continued to see breathtaking technical advancements, exemplified by special effects, that remain ongoing.

In that context, I have divided these evaluations into four eras: The Vintage Era, the Golden Era, the Modern Era, and Today's Era. Not coincidentally, these parallel the current structure of baseball's veterans committee, divided into four subcommittees: Early Baseball, Golden Days, Modern Baseball, and Today's Game. The distinctions, explained below in each section, apply primarily, albeit broadly, to filmmaking convention since a staple of baseball movies is retrospective reflection of bygone eras.

So, take a break from the unfolding apocalypse and watch a baseball movie. Sometimes distraction is necessary. Especially now. Even if just for a little while. Enjoy.

I nearly forgot: No spoilers.

The Vintage Era

Movies reviewed in this section:

Alibi Ike (1935): 2.2 WAR

The Babe Ruth Story (1948): 2.0 WAR

Elmer, the Great (1933): 2.3 WAR

Fireman, Save My Child (1932): 2.3 WAR

It Happens Every Spring (1949): 3.6 WAR

Ladies' Day (1943): 2.2 WAR

The Pride of the Yankees (1941): 4.3 WAR

The Winning Team (1952): 2.1 WAR

What defines the Vintage Era? In baseball terms, this would be the Segregation Era prior to 1947, when Jackie Robinson became the first African-American to play in the 20th-century Major Leagues. (Meanwhile, Larry Doby, the Buzz Aldrin of integrated baseball, became the first African-American player in the American League, debuting with the Cleveland Indians about a month after Robinson's debut with the National League's Brooklyn Dodgers.)

In movie terms, the Vintage Era corresponds in a rough chronological parallel to baseball as three of these movies depict actual baseball players, all of whom played prior to integration: Pete Alexander, Lou Gehrig, and Babe Ruth. But "vintage" also refers to a movie-making style or convention, a throwback (pardon the expression) to a cinematic atmosphere of less realism and more sentimentality that describes three of these movies released after 1947—two of which do profile actual players.

However, before we get to the actual players, let's look at the fictitious ones.

To say that Joe E. Brown was the Kevin Costner of his time might be disingenuous. True, both made three baseball-themed movies. But while Costner is languid, blandly handsome, and credible portraying a baseball player (he did try out for the team at California State University, Fullerton), Brown, probably best-known now for pursuing Jack Lemmon (in drag) in Billy Wilder's legendary 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot, was voluble and homely and whose most distinctive feature was his satchel mouth—if Johnny Bench could hold seven baseballs in one hand, then Brown could hold seven in his gaping pie hole.

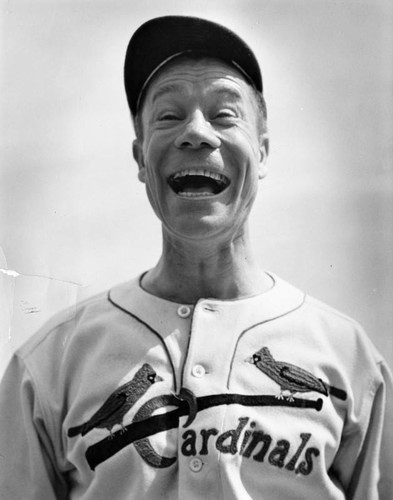

An unlikely baseball prospect? Joe E. Brown was actually scouted by the Yankees.

Yet Brown, who was already forty years old when he appeared in his first baseball movie, the comedy Fireman, Save My Child (2.3 WAR), had played professional (non-Major League) baseball in his prime and had once been scouted by the New York Yankees. Moreover, Brown's baseball interests continued long after he made his baseball movies. In 1953, he became the first president of the Pony League (now known as PONY Baseball and Softball, with PONY an acronym for Protect Our Nation's Youth, and from whose ranks rose future Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn and Cal Ripken, Jr.), remaining in that post until 1964 as he strongly advocated for youth baseball.

Furthermore, his son Joe L. Brown became the general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955 to 1976. During those two decades, he presided over the Pirates' World Series victories in 1960 and 1971 with squads that included Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente, Bill Mazeroski, and Willie Stargell; the younger Brown returned from retirement in 1985 to steady a Pittsburgh franchise rocked by the drug scandals that dogged several Pirates players, including star slugger Dave Parker, along with several non-Pirates players including eventual Hall of Famer Tim Raines (who reputedly slid into many of his 808 career stolen bases head-first so he wouldn't break the glass vial of cocaine he kept in his back pocket).

Nevertheless, none of Joe E. Brown's baseball movies, starting with Fireman, Save My Child, are any great shakes despite evincing Brown's love of the sport. Despite its unusual title, Fireman was actually the third movie made under that title in a 14-year span, and although firemen figure into the stories of all three movies, all three have different storylines, with Brown's the only one to feature baseball. Screenwriters Arthur Caesar, Roy Enright, and Robert Lord work the national pastime into a loopy tale about "Smokey Joe" Grant (Brown), a fireman in small-town Rosedale, Kansas, who invents a "fire extinguisher bomb," a chemical cocktail packed into a softball-sized container that can blow out fires instantly, and who also happens to be the pitching ace of the local team.

But despite Brown's wild wind-up, curb those jokes about the "fireballing right-hander" because baseball is the pretext to launch Fireman's breezy, wacky narrative directed by Lloyd Bacon. Determined to both patent his invention and marry his hometown sweetheart Sally Toby (Evalyn Knapp), Joe finally accepts the Cardinals' offer to go pro. Off he goes to St. Louis, where he leads the Redbirds to the World Series, but two shady operators steer the rube toward con artist June Farnum (Lilian Bond) looking to bilk Joe of his money by making herself his fiancée—and you know Sally, the Big Game, and a Really Big Fire have to factor into the, er, incendiary conclusion.

An amusing, compact trifle, Fireman also displays Smokey Joe's penchant to chase fire engines even right in the middle of the game, a sly reference to the same eccentric behavior of colorful Hall of Fame pitcher Rube Waddell, as well as cinematographer Sol Polito's early attempts at a "catcher cam" recording the ball coming into the hitter from Smokey Joe's funky wind-up. And although Brown's Smokey Joe, a starting pitcher in addition to being a firefighter, does make a relief appearance at a most crucial time, there is no evidence that this might be the origin of a reliever being called a "fireman" coming in to douse late-inning rallies (although it should be). Most significantly, Fireman, Save My Child established the template for Brown's two subsequent baseball comedies: distracted baseball star shrugs off his talent, fumbles with the girl, and falls in with unsavory types looking to exploit him.

First up is Elmer, the Great (2.3 WAR), with Brown this time a bush-league slugging sensation from Gentryville, Indiana, whose contract is bought by the Chicago Cubs, but despite histrionic entreaties by his brother Nick (Sterling Holloway), Elmer is strangely indifferent to playing in the big leagues. (And this is before the Cubs' curse of the Billy goat.) Why? Because lazy Elmer would rather sleep late, then wake to a gargantuan breakfast prepared by his mother (Emma Dunn). His only other interest is hometown honey Nellie Poole (Patricia Ellis), who, in order to spur Elmer to Chicago, rebuffs his advances. Downcast, Elmer nevertheless becomes a rookie "pheenom," leading the Cubs to, as he dubs it, the "World Serious." Elmer's country rube is ripe for practical jokes by his jealous teammates, which include luring him into a phony radio broadcast with glamorous actress Evelyn Corey (Claire Dodd), who falls for him—just as Nellie arrives to visit Elmer.

The other complication involves Elmer's getting mixed up with gamblers during the World Series against the New York Yankees, an allusion to the actual 1919 "Black Sox" World Series scandal that tarnished baseball—and that will resurface again during our evaluations. (The Cubs actually did face the Yankees in the 1932 World Series, most notable for Babe Ruth's famous "called shot" while facing Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, although Brown's Elmer makes no such gesture here.)

Joe E. Brown gets ready to crush one as the talented but lazy slugger Elmer, the Great.

That gambling interference was a theme that haunted Ring Lardner, the famed sports columnist and devotee of the Chicago White Sox who felt betrayed by the team's scandal ("the faith of fifty million Americans," as F. Scott Fitzgerald put it in his novel The Great Gatsby, a phrase that Ken Burns later picked up for his documentary Baseball); Lardner scripted Elmer, the Great based on his musical play co-written with the legendary George M. Cohan, and Lardner would also script Brown's third baseball movie. As for Elmer itself, it's another lovable-lunkhead vehicle for Brown that tries to rally around its thin gags but ultimately fails to score.

Brown's third and final baseball movie, Alibi Ike (2.2 WAR), finds him back on the Cubs but this time back on the mound with that wild wind-up of his before he fires a heater across the plate. Frank Farrell (Brown) might not have a screwball in his repertoire, but everything else about this zany but slight baseball comedy is screwball. Truth be told, Frank had better be an ace hurler because his tendency to proffer excuses for just about everything leads to untold—albeit predictable—complications in this one-pitch adaptation by William Haines of Lardner's short story about the country phenom who makes it to the big leagues but can't quite shake his rube image. Again.

He also can't quite shake Dolly Stevens (Olivia de Havilland) either, the fetching sister-in-law of his manager Cap (William Frawley), whose exasperation with Frank usually abates once he's managed to secure a win for the surging Cubbies. (De Havilland would soon graduate to the movie Major Leagues herself, becoming a two-time Academy Award winner for Best Actress as one of the stars of Hollywood's Golden Age; amazingly, she is still alive at age 103 as of this writing. Meanwhile, Frawley went on to co-star in the landmark television sitcom I Love Lucy.)

No excuses for star power: Brown really gets the girl in Alibi Ike. Olivia de Havilland--she's the one on the left--went on to win two Best Actress Oscars, neither one for this tepid time-filler.

Frank's inability to come clean leads him to pretend that the love letters he exchanges with Dolly are really from some vague "friend," but when Dolly is affronted by his excuses about her and leaves him, he becomes despondent—and susceptible to gamblers wanting him to sully the Cubs' pennant chances. Again. Director Ray Enright executes the slapstick silliness with smooth economy, but this is one narrative that needs a stronger cover story to be substantial and engaging—and credible: The litany of Frank's alibis is pure contrivance to keep a tired punchline going. Furthermore, Alibi Ike needs to explain how the Cubs, the last team to have lights installed in their own ballpark in 1988, manage to play a night game at home in the 1930s.

Vernon Simpson (Ray Milland) is also a hurler with girl troubles of his own as gentle comedy ensues when science collides with baseball in It Happens Every Spring (3.6 WAR), but although he really loads up the ball to get an edge over hitters, he is only doing it to win the hand of Debbie Greenleaf (Jean Peters), daughter of the president of the college (Ray Collins) where Vernon toils as a baseball-loving chemistry teacher trying to develop an insecticide to protect trees. However, when an errant baseball destroys his equipment and his experiment (keep an eye out for Alan Hale, Jr., the Skipper from Gilligan's Island, as one of those responsible), he discovers that the surviving residue repels wood—an ideal substance with which to doctor a baseball so it avoids contact with baseball bats.

That premise—yes, it screams "cheater" but just roll with the comedic possibilities—drives the breezy screenplay by Valentine Davies, from a story by Davies and Shirley Smith, compelling Vernon—now billing himself as "Kelly"—to persuade the St. Louis baseball club to hire him as a pitcher, where he hopes to make the money he had planned to make from his invention. Both manager Jimmy Dolan (Ted De Corsia) and owner Edgar Stone (Ed Begley) are understandably skeptical until they see the unusual hop Vernon can put on the ball—then they hire him while assigning catcher Monk Lanigan (Paul Douglas) as Vernon's battery- and roommate.

Ray Milland's game face in It Happens Every Spring. Well, not necessarily.

As St. Louis, behind Kelly's improbable pitching, drives toward the pennant, director Lloyd Bacon spurs the narrative along, emphasizing the budding friendship between unlikely pals Monk and Vernon while Vernon tries to conceal his new alter ego from his old alma mater and the increasingly curious Debbie. Milland is quietly appealing and Peters is reliably earnest while Douglas supplies comic color along with Jessie Royce Landis as Debbie's mother. (We will see Douglas crop up in a bigger role shortly.) The actual baseball is credible enough—leaving aside the doctored ball that would send Gaylord Perry into an orgiastic frenzy—for the delightful, if implausible, It Happens Every Spring, even if it never actually states which St. Louis team Kelly is pitching for.

Speaking of implausible, Ladies' Day (2.2 WAR) makes no bones about being anything but a trifling baseball farce that never rises above one joke stretched ad nauseam, yet it manages to coax attention much like a late-inning, come-from-behind rally in a hopeless blowout—the odds are extreme, but there's always that slim chance. And although Eddie Albert and Lupe Vélez receive top billing, it's the supporting cast that carries the day in this adaptation of the 1939 play by Robert Considine, Edward Lilley, and Bertrand Robinson by Dane Lussier and Charles Roberts, whose snappy if spotty script also plays coy with actual baseball names and events.

Eddie Alberts pitches a screwball--comedy, that it--as the improbably-named Wacky Waters in Ladies' Day, which at least knows how to use punctuation correctly.

Albert is Wacky Waters ("Dizzy Dean" was taken already), star pitcher for the "Sox" poised to lead them to victory in the 1941 "Big Series" as long as he's not distracted by dames. Naturally, he falls for movie star Pepita Zorita (Vélez), selling war bonds before a game, and his pitching falls apart. This incenses the other players' wives, who are counting on Series money, and led by Hazel Jones (Patsy Kelly), married to catcher Hippo (Max Baer), they scheme to keep them apart. Although Wacky and Pepita secretly marry, she is offered a film role that separates them, but when production wraps early, the wives snap into action to keep Wacky focused—and away from Pepita—until the Series is over.

All clear on that? Neither am I. This sloppy plotting—when exactly is Wacky wonky? and selling war bonds when the United States is not yet at war?—further weakens the one-joke premise, yet Ladies' Day avoids being cut entirely thanks to efficient direction by Leslie Goodwins and an engaged ensemble, led by Kelly, that includes Iris Adrian, Joan Barclay, Cliff Clark, Jerome Cowan, Tom Kennedy, and, finally, Vélez, playing off her "Mexican Spitfire" chica Latina persona with high-voltage histrionics that can only lead to her becoming a bound-and-gagged hostage in a hotel room. Ladies' Day fouls off a few before ultimately striking out.

Moving from wacky comedy to earnest biography, the next three movies celebrate three legends who are among the earliest inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame—but the quality of the movies commemorating their legacies varies wildly.

The worst of the three has to be The Babe Ruth Story (2.0 WAR), baseball's most famous player whose legendary feats on and off the diamond epitomize Americana—which makes this overweening, underwhelming, childish and risibly sanitized biopic a woeful, dismal failure with precious little to redeem it. George Callahan and Bob Considine based their script on Considine's biography, written with Ruth prior to Ruth's 1948 death from cancer, and from the opening canard, voiced by narrator Knox Manning, that repeats Abner Doubleday's bogus claim to have invented the sport, this three-base error slathers on the moldy Limburger to the mawkish end. (And recall that Considine is also partly responsible for the mediocre Ladies' Day.)

Poor William Bendix is tasked with portraying the larger-than-life slugger, and while the oafish shlub bears a (barely) passing resemblance to the later Ruth, Bendix's reputation as a comedic foil ensures that The Babe Ruth Story forfeits any semblance of plausibility and instead descends into a cartoonish, painfully enacted hagiography of Ruth's life. From a Baltimore reformatory, where George Herman Ruth learns to play baseball from mentor Brother Matthias (Charles Bickford), Rush becomes a pitching star for the Boston Red Sox, with fan Claire Hodgson (Claire Trevor) pointing out how Ruth was tipping his pitches.

William Bendix's revoltin' development: He gets to play the lead in The Babe Ruth Story, which strikes out an awful lot.

That's enough to eventually prompt him to marry her once he becomes a slugging superstar for the New York Yankees—but then this Ruthian legend turns to his youthful fans to ridiculous effect. Indeed, this juvenile narrative finds Ruth ducking a game to save a boy's dog while recasting his notorious "called shot" home run in the 1932 World Series as a promise to a hospitalized child, barefaced idolatry that whitewashes Ruth's more colorful adult escapades while avoiding any actual baseball action. Veteran director Roy Del Ruth's competency along with Bendix's and Trevor's stoic professionalism keep this one from complete awfulness, but The Babe Ruth Story is still both an embarrassment and an affront.

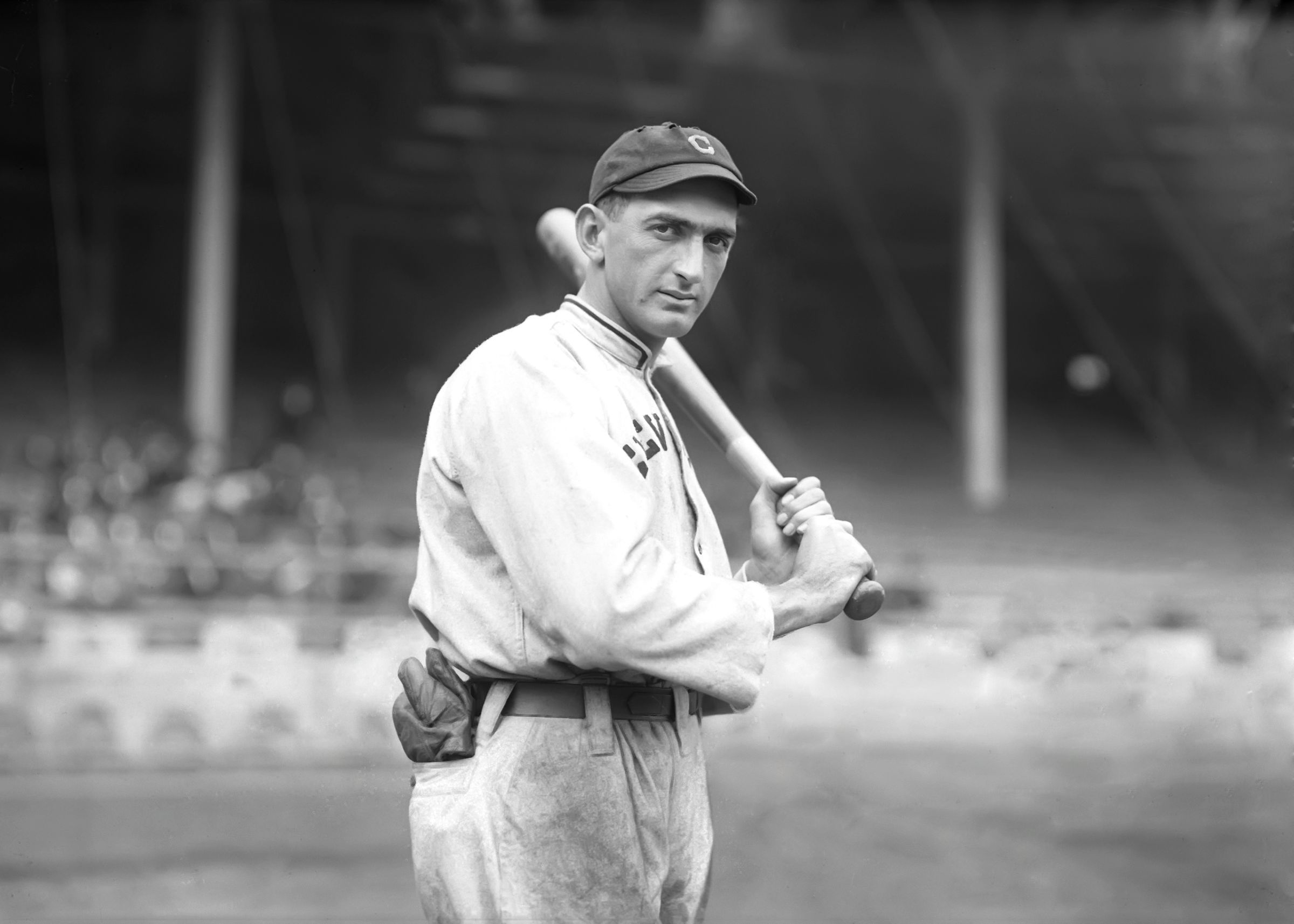

Only marginally better is The Winning Team (2.1 WAR), which finds future president Ronald Reagan portraying ace pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, but the "winning team" here isn't the 1926 St. Louis Cardinals, with whom "Pete" won his only World Series championship, defeating the New York Yankees largely on the strength of his coming into Game Seven in the bottom of the seventh inning with two outs to preserve the Cardinals' one-run lead by striking out Tony Lazzeri with the bases loaded for his only postseason save. Alexander had already pitched two complete-game victories, the second in Game Six, and according to legend, Alexander had been in the bullpen nursing a hangover resulting from his celebrating the night before when player-manager Rogers Hornsby called for him in the seventh. As we all know by now, baseball just lends itself to high—or even low—drama like this.

No, the "winning team" is instead that of Pete and his devoted wife Aimee, portrayed by Doris Day, who not only gets top billing over Reagan but also a singing spotlight. Indeed, this romanticized biopic, scripted by Merwin Gerard, Seeleg Lester, and Ted Sherdeman from Gerard and Lester's story, applies gauzy Hollywood whitewash to Alexander's biography even if it doesn't quite no-hit Alexander's struggles with alcoholism and epilepsy. A telephone lineman and semi-professional ballplayer, "Alex" plans to wed Aimee and buy a farm, but he makes the Majors with the Philadelphia Phillies, where he becomes an ace. Sold to the Chicago Cubs, Alex also serves during World War One and returns with more health issues exacerbated by his new drinking problem, which scotches his playing career and drives Aimee away. But she returns to implore Cardinals player-manager Rogers Hornsby (Frank Lovejoy) to give Alex another chance, and the rest is—

—Well, the rest is just as anodyne as the story up to now. Director Lewis Seiler handles this simple, soft-tossing script with journeyman efficiency as another journeyman, composer David Buttolph, couches the cliché in equally obvious and vapid musical sentiment. Rangy Reagan, amiable and league-average, gets a no-decision here while Day must project her devotion as Frank Ferguson, Eve Miller, and Frank Millican fill out the roster amidst The Winning Team's sentiment and simplicity. Reputedly, in his later years as president, Reagan, who loved to talk about his Hollywood days, regaled a visitor with how he had once portrayed President Grover Cleveland in a movie. The visitor had to discreetly remind the Gipper that he had portrayed Grover Cleveland Alexander, the baseball player, not the president for whom Pete was named.

The winning team in The Winning Team: Ronald Reagan (left) as pitcher Pete Alexander and Doris Day as his wife Aimee. One of them became president. Can you guess who?

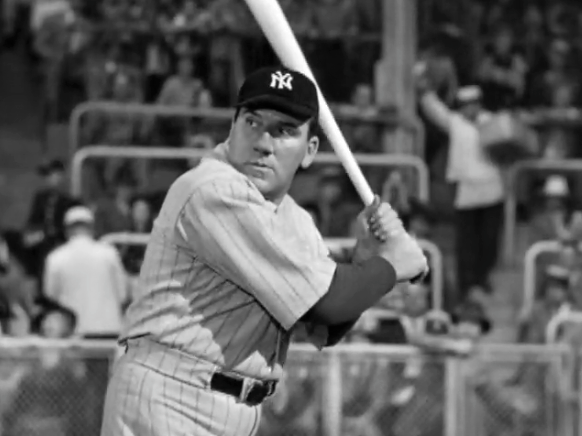

Much better, yet still displaying the pervasive sentimentality of baseball movies of the Vintage Era, is The Pride of the Yankees (4.3 WAR), although sentiment and other potent emotions cannot help but permeate this biopic of slugging New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig, with Gary Cooper portraying "The Iron Horse," whose consecutive-game record held for 56 years, and whose career was arrested when he contracted amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a fatal neural disease now named for Gehrig. (Gehrig died in 1941, just seventeen days shy of his 38th birthday.) Adapting Paul Gallico's book, this saccharine screenplay by Jo Swerling, Herman Mankiewicz, and Casey Robinson is keyed more toward domestic drama than to baseball dynamics.

The domestic drama begins with the relationship Gehrig has with his mother (Elsa Janssen), who wants her athletic son to become an engineer and escape their working-class milieu. But when she becomes ill, Gehrig, abetted by his father (Ludwig Stössel), foregoes his Columbia scholarship to become a professional baseball player and secretly subsidize the medical expenses. Naturally, she discovers this along with Gehrig's budding romance with Eleanor Twitchell (Teresa Wright), but is eventually won over when Lou becomes a superstar, and all is well until Gehrig slows down and winds up at the Mayo Clinic, where the news is not good.

An iconic shot from an iconic movie about an iconic ballplayer. Gary Cooper as the luckiest man on the face of the Earth: He got to portray Yankee Lou Gehrig on film.

Wright, who became typecast as the strong, supportive woman (Exhibit A is her role in 1946's The Best Years of Our Lives), seizes the emotional center as The Pride of the Yankees enters its final innings, moving from the gentle romance between Gehrig and Eleanor to a film with substance. Director Sam Wood conducts the story like a fairy tale, assisted by Rudolph Maté's solicitous photography and Leigh Harline's ever-fulsome score, while Cooper, propped up by real-life Yankees Bill Dickey, Bob Meusel, and Babe Ruth, delivers his trademark quiet stoicism, exemplified by Gehrig's iconic farewell speech. The Pride of the Yankees is well-executed cornpone, but Cooper and Wright manage to justify the film's continuing high regard.

The Golden Era

Movies reviewed in this section:

Angels in the Outfield (1951): 3.7 WAR

Big Leaguer (1953): 2.3 WAR

Fear Strikes Out (1957): 3.1 WAR

The Jackie Robinson Story (1950): 3.5 WAR

The Stratton Story (1949): 4.4 WAR

What defines the Golden Era? In baseball terms, this would be the period after integration and before expansion, a relatively short and narrow window but one that is appropriate as these five movies were all released in a less than ten-year span.

In movie terms, this also corresponds to baseball chronology but it also reflects a more concerted emphasis on realism and credibility. Four of the five movies are based on actual baseball personages, and while the fifth is not only fictional but is fantastical, it features credible baseball action while the off-field story, designed expressly to be touching, is both unconventional and free of conventional sentiment.

Notably, the four movies based on actual baseball figures all abandon the rich sentimentality of the Vintage Era, with all of them spotlighting realistic adversity, whether physical or mental hardship, racism, or simply the sheer effort it takes to reach the Major Leagues.

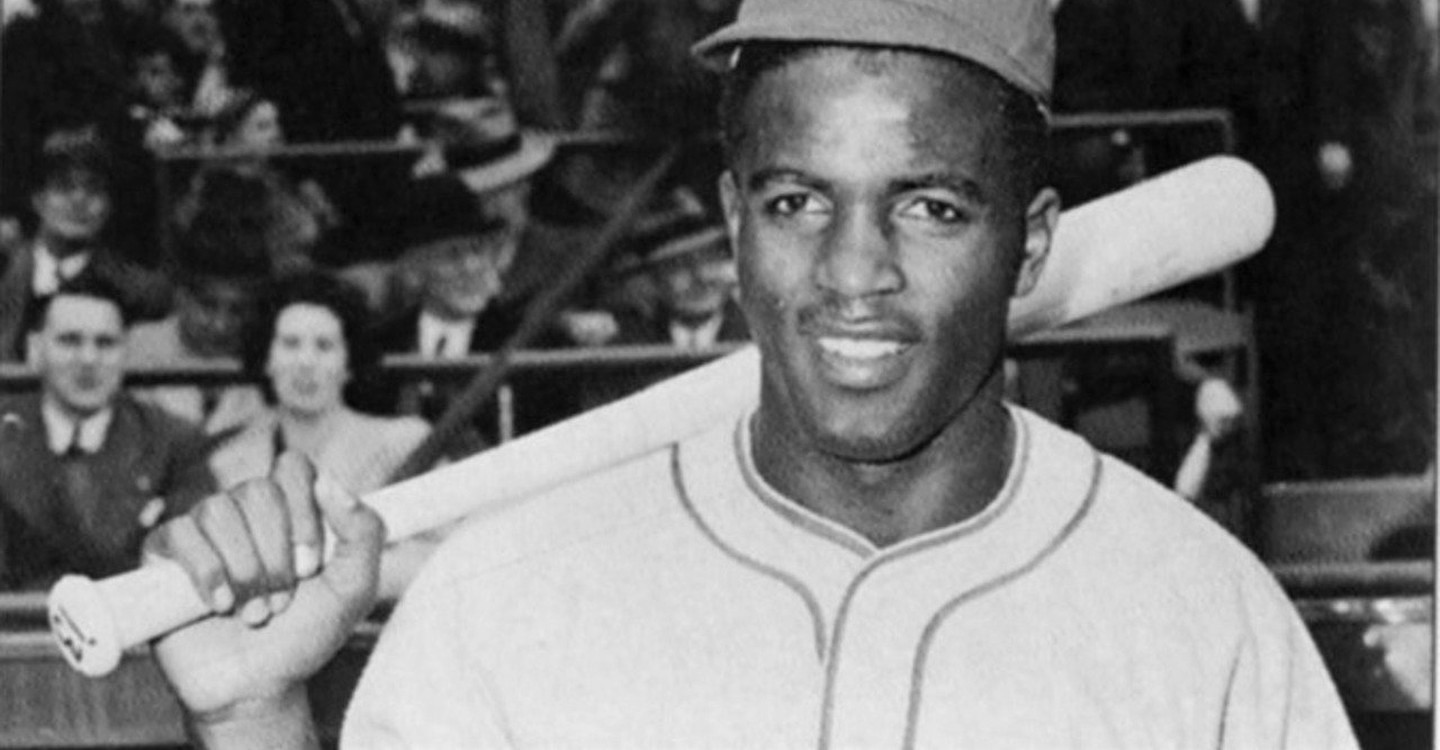

Leading off is The Jackie Robinson Story (3.5 WAR), unusual in the sense that it stars its very subject and was made at the height of Robinson's historic career as the first African-American player in 20th-century Major League Baseball, a courageous feat as he endured tremendous racial abuse to pave the way for African-American ballplayers. The Jackie Robinson Story soft-pedals much of that to yield an inspirational story, although it cannot ignore that reality as it presents a reasonably accurate portrayal of Robinson's travails through to his rookie season with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The script by Arthur Mann and Lawrence Taylor mixes grit with the gloss: Shown encouragement as a boy, Jackie becomes a four-sport star at UCLA, where his older brother Mack (Joel Fluellen) also starred—although Mack's college degree cannot help him professionally, which also plagues Jackie even as he meets nursing student and future wife Rachel "Rae" Isum (Ruby Dee). After a stint in the Army—also sanitized here, as he had been court-martialed as a result of racial prejudice—Robinson barnstorms in the Negro Leagues until Brooklyn's general manager Branch Rickey (Minor Watson), looking for a black player with both temperament and talent, signs him to an MLB contract.

The Jackie Robinson Story focuses on Robinson's apprenticeship with Brooklyn's farm team the Montreal Royals, where he learned to withstand the growing racial abuse before jumping to the Dodgers in 1947. Veteran character actor Watson delivers the best performance as his Rickey emerges alongside Robinson, who is serviceable as the star, with Dee and Louise Beavers, portraying Robinson's mother, carrying water while director Alfred Green steers the workmanlike narrative that keeps the themes of intolerance and acceptance visible throughout. Also workmanlike is the baseball action, although The Jackie Robinson Story transcends the box scores to illuminate a nobler contest.

We hope he didn't have to research the character too much: Jackie Robinson portrays himself in The Jackie Robinson Story. Not the only time we'll see a Jackie Robinson movie.

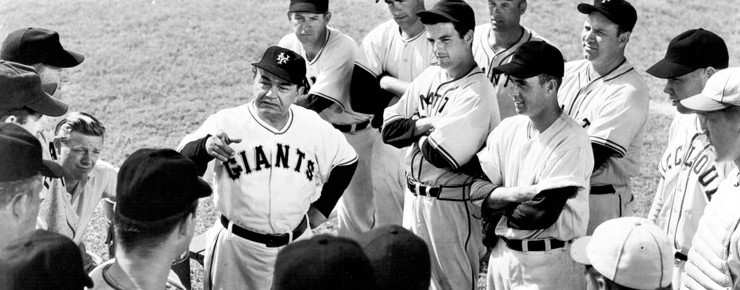

Of course, despite his daunting obstacle, Jackie Robinson flourished in the Major Leagues to become a Hall of Famer, but many players with none of the social and racial burdens Robinson faced never even make it to the Majors—and as Big Leaguer (2.3 WAR) demonstrates, often it can be a challenge even making it into the minor leagues. This earnest, journeyman baseball story, scripted by Herbert Baker from a story by John McNulty, offers an unusual glimpse at players trying to win a $150-a-month minor-league contract, which in turn could lead them to the Majors. Or not.

Hoping to make the grade even at the minor-league level: Edward G. Robinson as Hans Lobert, assessing potential Major League talent for the New York Giants in Big Leaguer.

Former big-leaguer Hans Lobert served as the technical advisor for Big Leaguer; he is portrayed by the unlikely Edward G. Robinson, who runs a training camp for the (then-) New York Giants. Among the young hopefuls are Bobby Bronson (Richard Jaeckel), Julie Davis (William Campbell), Tippy Mitchell (Bill Crandall), and Chuy Aguilar (Lalo Rios), although the prime prospect is strapping Adam Polachuk (Jeff Richards, a former minor leaguer), who catches the eye of Christy (Vera-Ellen), Lobert's niece from the Giants' front office, even as the brooding third baseman harbors a family secret that affects his play.

As Lobert whips the prospects through their paces—although dubious as a former ballplayer, Robinson nevertheless is a five-tool actor—many will inevitably not make the cut for the obligatory final game with its equally predictable heroics. Captured in William Mellor's black-and-white cinematography, the on-field action looks credible enough—these are prospects not yet fully formed—although the off-field dramatics are less so: Polachuk's romance with Christy is tepid contrivance, and his confrontation with his father (Mario Siletti) is just as pat, while other attempts to add dimension to the characters—Aguilar's halting English, Davis's braggadocio, Bronson's cut from the squad—are perfunctory and obvious.

Pretty dubious as a ballplayer, even a retired one, Edward G. Robinson was still a five-tool actor.

Yet Big Leaguer does convey a feel for the game's hard realities, abetted by appearances from Brooklyn Dodgers coach Al Campanis and Hall of Fame pitcher Carl Hubbell, the Giants' real-life director of player development at the time. The film also marks rookie Robert Aldrich's debut as a director (Kiss Me Deadly, The Dirty Dozen, The Longest Yard) in the cinematic majors, and while Big Leaguer doesn't make the cut, there's always next year.

But even if a player makes it to the Majors, any number of misfortunes could strike beyond simple performance issues, as the next two movies illustrate. For Monty Stratton, a strapping right-hander who was beginning to blossom as a starting pitcher for the Chicago White Sox, turning in back-to-back 15-win seasons in 1937 and 1938 while posting a sterling 2.40 ERA with five shutouts in 1937 during a period of high offense, an offseason hunting accident ended his Major League career: Hunting rabbits on his family farm in November 1938, Stratton fell and accidentally discharged his shotgun, severing an artery in his thigh that forced the amputation of his right leg.

However, that is not the end of The Stratton Story (4.4 WAR) because, as portrayed by James Stewart, Monty Stratton, fitted with a prosthetic leg, continued to pitch in the minor leagues from 1946 to 1953. Stewart embodied a distinctive American male archetype, modest but determined, decent but quietly defiant in the face of adversity, and it is that pluck that drives Douglas Morrow and Guy Trosper's script, which won a Best Story Oscar, as director Sam Wood, recalling his approach from Pride of the Yankees, puts Stewart and June Allyson squarely at the center of this sentimental yet effective biopic.

Allyson portrays Ethel, whom Monty meets soon after making the White Sox thanks to scout Barney Wile (Frank Morgan), a washed-up catcher looking to get himself back into the majors. Barney poaches Monty from his Texas farm and his skeptical mother (Agnes Moorehead, a crucial lineup fixture if ever there was one), who relents when Monty returns with Ethel, now his wife and mother of their infant son, as his big-league career seems to be in full swing, at least until Monty accidentally shoots himself in the leg.

A career-ending tragedy? Not so fast. Pitcher Monty Stratton (James Stewart) gets a new leg up in The Stratton Story.

Stewart looks credible as a strapping right-hander, and the baseball action, buttressed by actual Major Leaguers Gene Bearden, Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, and Jimmy Dykes, seems close enough, but The Stratton Story is really the story of Monty and Ethel, who stands firmly by her man, and the natural, engaging chemistry between Allyson and Stewart is the true all-star here as Adolph Deutsch's eager score never fails to accent noticeably. Wood's sharp direction, framed in Harold Rosson's clear black-and-white photography, builds to the requisite big-game climax, but that carries poignancy as The Stratton Story triumphs thanks to the winning Allyson-Stewart battery.

At least Stewart looks like a ballplayer in The Stratton Story. Just don't bunt on him because that's really hitting below the belt.

Already we've seen another standard trope, that of the unsung person, typically a woman, standing behind the prominent man, whether it's Monty's wife Ethel here, or Pete Alexander's wife Aimee in The Winning Team, or Lou Gehrig's wife Eleanor in The Pride of the Yankees, or even Babe Ruth's wife Claire in The Babe Ruth Story. But sometimes the prominent man doesn't have a positive source behind him, and in the case of Jimmy Piersall, he has a psychological impediment hampering him further still.

A two-time Gold Glove center fielder notably for the Boston Red Sox, which he represented in two All-Star games, Piersall, early in his Major League career, displayed erratic behavior that could become violent, such as picking fights with opponents and teammates alike; this was described as "nervous exhaustion" at the time but was symptomatic of bipolar disorder, which Piersall described in his 1955 book Fear Strikes Out, co-authored by Boston sports writer Al Hirshberg, which in turn became the basis for the movie Fear Strikes Out (3.1 WAR) that stars Anthony Perkins as Jimmy Piersall.

Anthony Perkins looks like he's afraid he'll strike out in Fear Strikes Out as he portrays Boston Red Sox outfielder Jimmy Piersall.

Director Robert Mulligan and screenwriters Ted Berkman and Raphael Blau take dramatic license with Piersall's story—to the point that Piersall ultimately dismissed the film—while Perkins, an unlikely-looking specimen as a ballplayer, does have his scenery-chewing moments that strain credulity. On the other hand, Perkins does make Piersall's episodes persuasive by displaying great range, shifting seamlessly from self-effacing to cocky to paranoid and pugnacious to reflect Piersall's churning state of mind. His performance, then, provided the model for his unassuming young man who can turn psychotic in the blink of an eye, a successful approach but one that, unfortunately, left Perkins typecast after he made that transformation immortal in Psycho three years later.

Save some of that for Psycho, Tony. Anthony Perkins (right) in Fear Strikes Out.

Mulligan's film makes it clear from the outset that Piersall's stresses stemmed from his father John (Karl Malden in an equally impressive performance), who pushed Jimmy to baseball greatness from boyhood (Peter J. Votrian plays the young Jimmy) and who withheld approval for anything less than perfection. The duel here is between Perkins and Malden, as Norma Moore (as his wife Mary) and especially Perry Wilson (as his mother) are kept on the bench, although Adam Williams as the doctor who engineers Piersall's breakthrough gets an at-bat. The actual baseball action in Fear Strikes Out waits in the on-deck circle while the psychological drama strides to the plate, gets on base—but fails to score in this mildly interesting baseball melodrama.

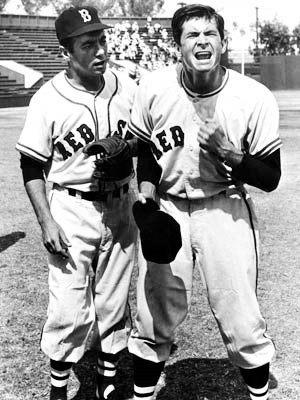

The one fictional baseball movie in this set, Angels in the Outfield (3.7 WAR), even has a supernatural premise, but it and the actual baseball action are surprisingly plausible. In the latter instance, that's because there are real baseball players in the action, including Hall of Famers Ralph Kiner, Pie Traynor, and Paul Waner (although only Kiner, an active player at the time, is actually out on the field), while Hall of Famers Joe DiMaggio and Ty Cobb make wry cameos along with actor and crooner Bing Crosby.

And in case you're noticing a pronounced Pittsburgh Pirates influence—Kiner, Traynor, and Waner all played for the Pirates, while Crosby was a part-owner at the time—that's because divine intervention does come to Pittsburgh to help the hapless Pirates score on the baseball diamond thanks to a little girl's prayers, but the biggest beneficiary may be the team's pugnacious manager Guffy McGovern (Paul Douglas), just as apt to throw a punch as unleash a string of obscenities in this winsome, modest comedy.

Dorothy Kingsley and George Wells scripted Richard Conlin's story that succeeds through suggestion rather than exhibition, puckishness rather than piety, with Douglas gliding from surly belligerent to serene surrogate with sly agility and surprising believability as the Pirates' fortunes rise—recall that Douglas made a memorable start in our Vintage Era baseball movie It Happens Every Spring. Already under fire by boo-birds like broadcaster Fred Bayles (Keenan Wynn), whom he helps to get fired, Guffy is assailed by pinch-hitting reporter Jennifer Paige (an engaging Janet Leigh), usually the "Household Hints" editor, in an article that gets her into the sports-page lineup.

Sentiment and supernatural assistance--yet Angels in the Outfield (1951) avoids being gloppy or corny.

But Guffy has an ally: orphaned moppet Bridget White (quietly adorable Donna Corcoran), whose fervent prayers for him and the Pirates moves an unseen angel (voiced by James Whitmore) to promise Guffy some heavenly help if he cleans up his act. And when Bridget claims to see angels on the playing field, Jennifer's story reporting it becomes a sensation—prompting still-resentful Bayles to clip Guffy's wings when he calls in Commissioner of Baseball Arnold Hapgood (Lewis Stone) to investigate Guffy's odd behavior.

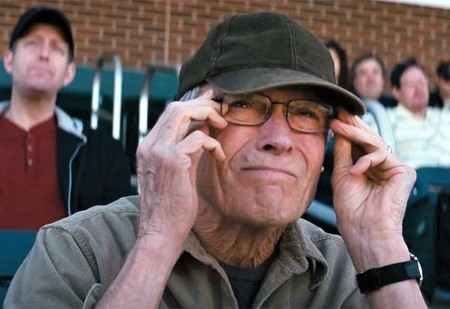

With credible on-field action, Angels in the Outfield, shot at the Pirates' then-home ballpark Forbes Field, flashes authenticity although producer-director Clarence Brown's focus is ultimately on the off-the-field story that brings Guffy, Jennifer, and Bridget together as a touching, albeit unconventional, unit refreshingly free from bathos or sentimentality, although Bruce Bennett's fate as an over-the-hill pitcher supplies poignancy, making Angels in the Outfield more heartwarming than the gloppy contrivances of Field of Dreams—which we'll get to shortly. (Speaking of gloppy, I have not seen the 1994 remake of Angels in the Outfield, but as it's a Walt Disney movie I shudder to think of the layers of sentimental syrup that drown the premise.) Finally, keep an eye out for Barbara Billingsley, later to play June Cleaver in the sitcom Leave It to Beaver, in an uncredited minor role. (Hint: Look in the restaurant scenes.)

A touching, albeit unconventional, team (L-R): Janet Leigh ("Jennifer Paige"), Donna Corcoran ("Bridget White"), and Paul Douglas ("Guffy McGovern") discuss whether there really are Angels in the Outfield.

The Modern Era

Movies reviewed in this section:

The Bad News Bears (1976): 4.8 WAR

Bull Durham (1988): 5.0 WAR

Eight Men Out (1988): 5.0 WAR

Field of Dreams (1989): 2.0 WAR

A League of Their Own (1992): 4.5 WAR

Major League (1989): 4.4 WAR

Mr. Baseball (1992): 3.2 WAR

The Natural (1984): 3.2 WAR

Soul of the Game (1996): 3.3 WAR

What defines the Modern Era? In baseball terms, this is the era of both league expansion and tiered postseason play, although only one of these movies is actually set in Major League Baseball during this era.

In fact, in movie terms, all the other films are split between gauzy nostalgia for earlier eras—although at least one of them lifts the gauze for a harder examination—and, intriguingly, perspectives on baseball other than at the Major League level—and not just in the United States—with one movie managing to split the difference.

The nostalgia movies harken back to the sentimentality of earlier baseball movies—one of them egregiously so—while the contemporary movies have a sardonicism that can be both refreshing and hilarious. But all of them have strong production values while flashing fairly credible baseball action—even when the baseball is supposed to be deliberately bad.

Looking at the movies in this era, though, it is tough not to say that this, at least from a cinematic perspective, is the real "Golden Era" for baseball movies, with a number of these titles among the most popular and well-regarded of any baseball movies.

A prime example of this is one movie in which the baseball is supposed to be deliberately bad, but whose impact is hilariously brilliant. I speak of course about The Bad News Bears (4.8 WAR), which taught us that life's bittersweet lessons can be found anywhere, and for The Bad News Bears they're learned on the Little League baseball diamond: It's not whether you win or lose but, rather, how you hold a grudge.

Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau) contemplating tough decisions as the coach of The Bad News Bears.

Bill Lancaster's ribald script skewers mid-1970s American middle-class suburbia with a refreshing lack of sentimentality even as this uproarious satire slyly celebrates that hoariest of sports-film tropes, the Cinderella story, with a rainbow coalition of misfits and losers led by a most unlikely—and reluctant—inspiration. Once a minor-league pitching prospect, Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau) now cleans pools to support his drinking habit until he's paid to coach the Bears, which, thanks to a class-action suit, were created within an ultra-competitive Little League somewhere within the ocean of suburbs in Southern California.

The motley squad includes corpulent catcher Engelberg (Gary Lee Cavagnaro), asthmatic benchwarmer Ogilvy (Alfred Lutter), and pugnacious shortstop Tanner (Chris Barnes), and when they get creamed in the season opener by the Yankees, coached by taskmaster Roy Turner (Vic Morrow), Buttermaker must seeks ringers. One of those is pitcher Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O'Neal), the fireballing daughter of an ex-girlfriend, while the other, Kelly Leak (Jackie Earle Haley), a delinquent who terrorizes the ball fields on his Harley-Davidson dirt bike, just happens to be a slugging sensation, but the Bears' unlikely but inevitable climb toward the championship holds unforeseen challenges.

Keeping your ace focused on the game: Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O'Neal, left) gets pitching pointers from Buttermaker (Matthau).

Director Michael Ritchie's sharp pacing and perceptive framing hits the strike zone consistently as Matthau's Buttermaker sets the acerbic tone, particularly his prickly, intriguing relationship with O'Neal's Amanda, with Jerry Fielding's spare but effective score, adapted from Bizet's Carmen, accenting memorably. Moreover, the kids display believable dimension without affect, with charismatic juvenile hellion Haley an especial highlight, although Barnes and particularly Lutter, who made an auspicious debut opposite Ellen Burstyn and Jodie Foster in 1974's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (which inspired the sitcom Alice), give him a run for his money. And who can forget bespectacled Stein (David Pollock), willing to take one for the team? All right, maybe not so willing.

Meanwhile, Morrow, tasked as the villain, soldiers on dutifully as the dad you love to hate, with Brandon Cruz, playing his son Joey, executing some classic 1970s nose-thumbing at authority (as well as at his own teammates) as The Bad News Bears cheekily defies convention. And how can you not love a team sponsored by . . . Chico's Bail Bonds? "Let Freedom Ring." (The Bad News Bears spawned two sequels and a remake, which if anything demonstrates how milkable the original remains.)

The Bears confer with their coach in The Bad News Bears. How can you not love a Little League team sponsored by . . . Chico's Bail Bonds?

But glorious ineptitude on the diamond is hardly restricted to Little League—it can even afflict the Major League (4.4 WAR), or at least the Cleveland Indians. At the time that writer-director David Ward made this enduring comedy, the Indians were a dilapidated franchise that had not won an American League

Pennant since 1954 (losing the World Series that year to the then-New York Giants, a Series most notable for "the Catch," Willie Mays's immortal defensive play in deep—I mean deep—center field in Game One), and they had not won a World Series since 1948; in fact, the Indians are still waiting to win a World Series despite three trips to the world championship since the movie was released, with their last two World Series appearances, particularly in 2016, among the most dramatic Series in baseball history.

Coming on like an unholy cross between The Bad News Bears and Airplane!, Major League shamelessly, gleefully expropriates the hoariest clichés from both baseball movies and actual baseball—the grizzled veterans, the hungry rookies, the heartless front office, and of course the Big Game—with utter predictability. And why not? Baseball is routine, repetitive, and predictable. Until it's not. Major League's wild thing is Ward's sleeper script that tips its pitches—until it doesn't—as it tosses out gags without belaboring them, producing belly laughs while slyly instilling a little sentiment.

Trophy-widow owner Rachel Phelps (Margaret Whitton) savors the downfall of the Cleveland Indians in Major League. Or is that premature?

Trophy widow Rachel Phelps (Margaret Whitton) is determined to sink the Cleveland Indians, which she now owns. Why? So she can move the team to greener pastures in Miami. That's why she restocks the already-moribund franchise with losers and misfits—career minor-league manager Lou Brown (James Gammon), broken-down catcher Jake Taylor (Tom Berenger), showboating walk-on Willie Mays Hayes (Wesley Snipes), and fireballing felon Rick Vaughn (Charlie Sheen), whose optical challenges yield his nickname "Wild Thing"—to join past-his-prime third baseman Roger Dorn (Corbin Bernsen), Voodoo-worshipping (and curveball-susceptible) slugger Pedro Serrano (Dennis Haysbert), and Holy Rolling, over-the-hill junkballer Eddie Harris (Chelcie Ross) for the final curtain.

Time to tame the Wild Thing (L-R): Tom Berenger ("Jake Taylor"), Charlie Sheen ("Rick Vaughn"), and James Gammon ("Lou Brown") confer.

Yet as the season progresses, Cleveland begins to rise from the dead, but can Phelps's sometimes-hilarious attempts at sabotage, such as cutting expenses for luxuries and amenities alike, ultimately tame the Tribe? One Airplane!-like gag has the team being shown an "alternate route" through the airport to board their charter flight, only to be led to a derelict Douglas DC-3—a propeller-driven airliner introduced into service way back in 1936—looking like a refugee from Casablanca.

Deluxe accommodations for the Cleveland Indians in Major League include this vintage Douglas DC-3, seemingly on the lam from some earlier movie, say Casablanca.

Top-billed Berenger gets dimension with his subplot to rekindle his relationship with swimmer-turned-librarian Lynn Weslin (Rene Russo), already engaged to a lawyer who is part of the downtown-chic crowd; upon learning that Jake plays for the Indians, one of them exclaims, "Here in Cleveland? I didn't know they still had a team!" Nevertheless, Major League is mostly a boys-only clubhouse, led by gravel-voiced anchor Gammon, with team announcer Harry Doyle (a riotous Bob Uecker) supplying sardonic narration that's just a bit outside the usual patter right up to the final play. (An alternate ending features a twist that rescues Phelps but smacks of too much contrivance.) James Newton Howard's bush-league score is synthetic pap, but using "Burn On," singer-songwriter Randy Newman's droll recounting of Cleveland's 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, over Major League's opening credits demonstrates smart pitch selection.

Still, the Indians wouldn't mind signing New York Yankees first baseman Jack Elliot (Tom Selleck), but the fictitious slugger winds up Japan playing for Nagoya's not-fictitious Chunichi Dragons in Mr. Baseball (3.2 WAR), and you already know that this American is going to experience Japanese culture shock both on and off the Nippon Professional Baseball field.

A hole in his swing you can drive a shuuto pitch through: Jack Elliot (Tom Selleck) navigates the finer points of Nippon Professional Baseball as Mr. Baseball in Mr. Baseball.

This workmanlike sports comedy endured a scripting saga, passing through a series of hands to satisfy both Selleck and Japanese sensibilities; what emerges is a heavily-massaged narrative as predictable as a lazy fly ball to straightaway center field, which still makes fans rooting for the team in the field happy, anyway. Jack certainly isn't happy with the deal as he feuds with his interpreter Yoji (Toshi Shioya), who has to tap-dance Jack's surly observations, and with his manager Uchiyama (Ken Takakura), whose bluster belies his front-office woes, while Jack flouts the team's routines and protocols.

Fellow expatriate player Max Dubois (Dennis Haysbert—yes, he was Serrano in Major League) offers exasperated advice, but when Jack spars with comely Hiroko (Aya Takanashi), who forces him to do an insipid television commercial as stipulated in his contract, their friction signals attraction as inevitably as a shuuto pitch induces Jack's swinging strikes—and just as inevitably, Hiroko turns out to be Uchiyama's daughter. Indeed, Jack's journey holds few surprises as he must overcome his batting slump and help the Dragons challenge the rival Yomiuri Giants for the pennant while he learns teamwork, humility, and respect—which we all know are sports-movie staples as requisite as the Big Game, which Mr. Baseball dutifully provides.

Really friends after all: Ken Takakura (left) and Tom Selleck in Mr. Baseball.

Director Fred Schepisi has a feel for the characters more so than for the game, although he does avoid most rookie mistakes, while veteran Jerry Goldsmith's score merely fills a roster spot. Selleck is serviceable, though he does swing a mean left-handed bat, with Takakura gaining strength in a sly sleeper performance as Mr. Baseball demonstrates that reliable sports clichés work in Japanese too.

At least Jack Elliot got to the Show. That's not a certainty, let alone a guarantee, for the players on the Durham Bulls, an actual Class-A team then in the Carolina League (although this story is fictional), save for one of them—if he can get his act together in time to make the late-season call-up to the Majors. Writer-director Ron Shelton knew of what he depicted in Bull Durham (5.0 WAR). As a second baseman, Shelton spent five years in the Baltimore Orioles farm system, working his way up to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings, and much of that experience gets channeled into one of the greatest baseball movies—hell, sports movies—ever made, not just because its portrayals of baseball ring with authenticity, but because its characters sing with distinction. making it a true Hall of Fame accomplishment.

Young girls don't get woolly, meat: Pitching phenom Nuke LaLoosh (Tim Robbins, left) and veteran catcher Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) don't always see eye-to-eye in Bull Durham.

Catcher Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) had a cup of coffee in the Show, but as a career minor-leaguer who never got another call-up, he has resigned himself to a more modest goal. However, that goal wasn't to be sent down to Class-A ball—and certainly not to mentor Ebby "Nuke" LaLoosh (Tim Robbins), a young, brash pitching phenom with Big League talent but Little League maturity. Resentful of Nuke for any number of reasons, Crash teaches him to respect his Hall of Fame arm, as well as to respect the game that can make him that Hall of Famer, with heated exchanges on the mound such as when Nuke, after shaking off Crash's call for a curve ball, says that he wants to "announce his presence with authority" with his fastball; that seemingly convinces Crash—who promptly tells the hitter what's coming next.

Economy or first class? Crash (Costner, left) and Nuke (Robbins) discuss accommodations on Nuke's gopher ball as Nuke learns another potentially big-league lesson in Bull Durham.

Complicating their already-adversarial relationship is Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon), a "baseball Annie" (to borrow the term Jim Bouton uses to describe a baseball groupie in his landmark exposé Ball Four) yet serial monogamist who selects Nuke as her lover for the season, to Crash's seeming chagrin. Nevertheless, she finds herself in league with Crash to prepare the mercurial Nuke for the Majors, and as Nuke's maturation improves the Bulls' fortunes, Annie and Crash see their initial mutual antagonism begin to dissolve.

Like most baseball plays, Bull Durham's love triangle offers routine, predictable reassurance, but it's the beauty inherent in the execution of those plays that fosters fans' admiration; similarly, Shelton makes nary an error in his depiction of the endless monotony legions of players endure in the hope of making it to the Majors—or not—with William O'Leary, Jenny Robertson, Trey Wilson, and Robert Wuhl bolstering the lineup. With Costner's quiet resignation providing the fulcrum, Sarandon's sexy eccentric balances Robbins's cocky bumpkin as Bull Durham not only displays its keen insight into the game, it celebrates all who worship in the church of baseball.

Bull Durham is notable for not only eschewing the obligatory Big Game, but, more importantly, for not even being set in the Major Leagues—in fact, it illustrates how difficult it is to even get to the Bigs, which only one of our previous movies, Big Leaguer, addressed seriously. But there was a time when it wasn't just talent—or a lack thereof—that kept a baseball player out of the Majors: the color of his skin automatically prevented that.

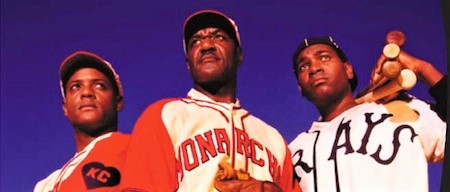

We have seen how The Jackie Robinson Story presented a sanitized, positive narrative of Robinson's historic achievement to become the first African-American Major Leaguer in the 20th century. Soul of the Game (3.3 WAR) broadens that scope to offer a salutary, sometimes bracing look at Robinson (Blair Underwood) and two other Negro League legends around the time of Robinson's 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers as it presents two of those legends, pitcher Satchel Paige (Delroy Lindo) and catcher Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson), as Robinson's de facto godfathers.

Negro Leaguers Jackie Robinson (Blair Underwood), Satchel Paige (Delroy Lindo), and Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson) contemplate the Soul of the Game.

Scripting Gary Hoffman's story, David Himmelstein illuminates the three against the backdrop of their personal and professional contemporaries with a series of pointed sketches that tend to overemphasize the emotions to the point of melodrama. Director Kevin Rodney Sullivan exacerbates that tendency with clipped, consciously underlined segments that encourage his cast to goose their performances, affectation that detracts from an otherwise-effective dynamic.

Paige, seemingly ageless yet clearly aging, and Gibson, supremely talented yet tormented by inner demons, spar as rivals on the diamond but foster their mutual ambitions off the field, foremost being their determination to play in the Majors. Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey (Edward Herrmann, in typically excellent form) is scouting Negro Leaguers for that goal, but he chooses Paige's teammate Robinson—younger, college-educated, more resilient temperamentally—to make that breakthrough, which only makes the increasingly-erratic Gibson more truculent, highlighted in scenes that might aim for poignancy but instead play as heavy-handed manipulation.

Rivals on the field, Satchel Paige (Delroy Lindo, pitching) and Josh Gibson (Mykelti Williamson, batting) both shared dreams of Major League glory.

Robinson remains the focus of Soul of the Game but a charismatic Lindo gets to display the most dimension as his Paige, a savvy showman and businessman, sublimates the indignities of segregation into his determination to succeed as Williamson, his Gibson struggling to articulate his frustrations, must weather an underdeveloped part; meanwhile, Salli Richardson-Whitfield, as Lahoma Paige, and Gina Ravera, as Grace, Gibson's girlfriend already married to another man, are saddled with the obligatory supportive-women roles, with Lee Ermey, Jerry Hardin, and Richard Riehle filling out the roster. Stringing together one carefully crafted teachable moment after another, Soul of the Game delivers laudable life lessons but falls short of an effective, engaging narrative.

Another barrier to entry into the Majors, whether around the time of Soul of the Game or at any other time, is gender. But as the United States entered World War Two in December 1941, the fate of the 1942 baseball season (as we are experiencing in 2020, although because of an entirely different kind of enemy) was seriously in question. Both major and minor leaguers were joining the ranks of millions of American men entering the armed forces, thinning not only rosters and bleachers but also forcing the decision of whether it was appropriate, or indeed patriotic, to continue playing Major League Baseball during time of war.

President Franklin Roosevelt ultimately decided that, yes, baseball was deemed essential to the war effort as a morale-booster for both the home front and the armed forces overseas. And just as women were moving en masse into wartime jobs in both public and private sectors, so too did women move into baseball. Formed in 1943, The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was initially conceived as a replacement for Major League Baseball, but with no interruption to MLB, the AAGPBL still went ahead, lasting until 1954.

Penny Marshall was inspired to make A League of Their Own (4.5 WAR) after watching a 1987 documentary of the same name about the AAGPBL, which she—like so many others including me—had never heard of before. She commissioned screenwriters Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel to work with the documentary's creators, Kelly Candaele and Kim Wilson, to script a fictionalized account of the league centered around a sibling rivalry between Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis), a hard-hitting catcher, and her kid sister, pitcher Kit Keller (Lori Petty).

Dirt in the skirt: Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis, batting) shows how the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League gets it done in A League of Their Own.

Make no mistake. Marshall, sister of television producer Garry Marshall, is nothing if not a product of television; even if she did establish a career as a feature-film director, Marshall still retained a sitcom sensibility, as did Ganz and Mandel, who wrote for Marshall's Laverne & Shirley comedy series as well as for the big screen. As a result, everything about this baseball comedy-drama conforms to sports movie cliché, right down to the finale's big-game showdown that pits the two principals against each other. Yet Marshall and her cast shine here because of the film's laudatory subject—and Marshall, ever-generous, even finds roles for her former Laverne & Shirley castmates Eddie "the Big Ragu" Mekka and especially David L. "Squiggy" Lander as a radio announcer broadcasting the games.

Oregonian farm girl Dottie is a phenom catcher whom scout Ernie Capadino (a scene-stealing Jon Lovitz) recruits for the new league; Dottie insists that her kid sister Kit, a pitcher, must come as well. In Chicago for tryouts, Dottie and Kit join saucy speedster Mae Morabito (Madonna), brash basher Doris Murphy (Rosie O'Donnell), and homely heavy-hitter Marla Hooch (Megan Cavanaugh), among others, on the Rockford Peaches, one of four teams in the league created by candy mogul Walter Harvey (Garry Marshall), based on real-life sponsor P.K. Wrigley, and run by believer Ira Lowenstein (ever-reliable David Strathairn, whom we'll see shortly in a more prominent role), who keeps the league afloat when initial interest sours.

Combing the sticks for talent: Baseball scout Ernie Capadino (Jon Lovitz) makes his pitch to Dottie and her sister Kit in A League of Their Own.

Tom Hanks is terrific as Jimmy Dugan, an alcoholic former big-league slugger, loosely based on Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx, tapped to manage the Peaches; his professional relationship with Dottie forms the heart of this movie along with Dottie and Kit's rivalry, which culminates in the big-game showdown as Ganz and Mandel keep the slick dialog flowing around both slapstick and sentiment. There might not be any crying in baseball, but A League of Their Own pitches its heartwarming laughs right across the plate.

Game's gettin' excitin', huh? (L-R) Pitcher Kit Keller (Lori Petty), manager Jimmy Dugan (Tom Hanks), and catcher Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis) confer in A League of Their Own.

One brief scene in particular shines for me, consciously crafted as one of those lump-in-the-throat moments that still does its job. During the tryouts at Wrigley Field, a ball rolls out to the warning track, near where an African-American woman is walking; she's well-dressed but clearly not included in the all-white activities as baseball, even at the AAGPBL level, is still segregated. She retrieves it—then uncorks a Roberto Clemente-like throw that sails into the infield, where Dottie catches it. All it takes are two silent nods—the black woman's nod of assertion, and Dottie's nod of acknowledgement—for the tingling to blossom at the back of my neck. And talk about attention to detail—check out how instinctively Marla backs up the play behind Dottie.

Marla Hooch--what a hitter! Actually, homely heavy-hitter Marla (Megan Cavanaugh) can flash a little leather out there at second base, too.

Actual events and personages also inform Eight Men Out (5.0 WAR), based on Eliot Asinof's true account of how eight players on the Chicago White Sox conspired with gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series and thus trigger a monumental scandal whose repercussions reverberate even today. Just ask Pete Rose about that.

Who are the White Sox and who are the "Black Sox"? Eight players helped gamblers fix the 1919 World Series in the historical drama Eight Men Out.

Recall from the Vintage Era how sportswriter Ring Lardner was haunted by this 1919 "Black Sox" scandal that rocked not just baseball but American society (Fitzgerald's "faith of fifty million," remember?). Two of Lardner's stories made into baseball vehicles for Joe E. Brown, Elmer, the Great and Alibi Ike, featured gamblers angling to corrupt Brown's talented rube, with the real-world analog being White Sox star outfielder "Shoeless Joe" Jackson, whose lifetime batting average of .356 is topped only by Ty Cobb's (.367) and Rogers Hornsby's (.358), but whose involvement in the scandal has still kept him ineligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame. A fan favorite, Jackson's saga is encapsulated by the (in)famously apocryphal newspaper account (demonstrating that "fake news" has always been with us, but I digress) of kids confronting their hard-hitting idol after revelations about his helping to throw the World Series, with one pleading, "Say it ain't so, Joe," to which Jackson must reply that it is.

Say it ain't so, Joe: Buck Weaver (John Cusack, left) gets caught in the middle of the scandal that also implicated superstar Joe Jackson (D.B. Sweeney).

Still, it's an account too good not to include in Eight Men Out as John Sayles not only wrote and directed this rich dramatization of the scandal, he portrays Ring Lardner as he and fellow sports reporter Hugh Fullerton (Studs Terkel) start keeping track when they realize that a fix must be on as the heavily-favored White Sox—a powerhouse team that finished 36 games above .500 to win the 1919 American League pennant (yet finished only 3.5 games ahead of a Cleveland Indians squad that featured future Hall of Famers Stan Coveleski and Tris Speaker)—start to struggle against the underdog Cincinnati Reds. (In actuality, the Reds finished 52 games above .500 and nine games ahead of the New York Giants—in other words, they hardly scraped into the World Series.)

With cinematographer Robert Richard applying the appropriate sepia tones, Eight Men Out harkens back to the vintage days of baseball although it is poles apart from the myths and melodramas of bygone baseball films. Sayles betrays not a whiff of nostalgia or sentimentality as he strives to convey both the burgeoning Jazz Age and the World Series diamond with realistic verité, succeeding impressively with an overarching ambition and attention to detail along with the actors' engaged portrayals and overall baseball-playing believability.

White Sox owner Charles Comiskey (Clifton James) assembles a championship team managed by former player Kid Gleason (John Mahoney), but his notorious parsimony made some players susceptible to offers to throw the World Series and thus lose it for more money than they would make for winning it. Although the term "Black Sox" came to describe the 1919 White Sox once the scandal came to light, it appears to have been used prior to the Series to describe the team. Not that the team was taking dives or cheating (there have been no reports of trash cans being banged during White Sox home games in 1919, for instance), but they may have been "playing dirty": Comiskey was such a skinflint that he actually made the players pay for their own laundry (calling Indians owner Rachel Phelps from Major League!), so in protest they allegedly played with dirty uniforms including "black socks."

"Black Sox" in more ways than one: The White Sox try to turn two the gritty way as part of the on-field baseball action in John Sayles's Eight Men Out.

Enter Boston gambler Sport Sullivan (Kevin Tighe) and a pair of his small-time grifters, "Sleepy" Bill Burns (Christopher Lloyd) and Billy Maharg (Richard Edison), who learn of the Sox's disgruntlement with Comiskey and broach an offer with first baseman Chick Gandil (Michael Rooker) to play poorly in the upcoming World Series in exchange for a bigger payoff ultimately supplied by legendary racketeer Arnold Rothstein (Michael Lerner). Needing more key players to help put the fix in, Gandil recruits pitcher Lefty Williams (James Read), infielders Swede Risberg (Don Harvey) and Fred McMullin (Perry Lang), and outfielders Happy Felsch (Charlie Sheen) and, haltingly, Joe Jackson (D.B. Sweeney).

Two other players prove pivotal. One is infielder Buck Weaver, who is aware of the fix but plays cleanly in the Series—although neither does he come clean about his knowing that there was a fix in place. John Cusack portrays Weaver as Sayles's fulcrum in Eight Men Out, its conscience conflicted by loyalty to his teammates, all with a mutual animosity toward Comiskey, and by his need to respect the game and, at the risk of waxing too grandiose, maintaining the faith of those fifty million Americans in the national pastime. By turns petulant, cowed, and outraged, Cusack acquits himself convincingly.